![]()

1

Private Pain and Public Display

It is crucial that we begin with precise and objective reports of what people and animals do when injured. The reports do not match the expectation of the victim or of the observer. In exploring the nature of pain, it will be necessary to separate reality from what we think ought to be observed. We will start with sudden events where a previously “normal” being is abruptly converted to a “sick” one. Of course, no such event occurs in a vacuum, as there is always a surrounding scene and the victim arrives at the accident with a personal and genetic history. Later, we will have to incorporate the vastly more common and less dramatic situation in which the onset of disease and pain is insidious.

A Swiss Army Officer

A forty-three-year-old reserve major, described by his wife as tough and taciturn, was skiing with his squad in the Upper Engadine region of Switzerland when a snow bridge collapsed below him. He remembers free falling into a crevasse with ice walls in front and behind, and scraping down one wall. With a tremendous crash and thump, he found himself wedged firmly in the ice crack. One arm was jammed above his head and he could not move his legs. He remembers hearing his gun and ski poles rattling down below, deeper into the crevasse. He was winded but was surprised to feel no pain whatsoever. He looked up and saw his men peering over the brink, and called out that he was all right but could not move.

A man was lowered down to him on a line and put a sling around him. The men above hauled on the ropes, and he remembers his relief on feeling himself swaying free. They carried him down to an open area and radioed for a helicopter, which arrived after twenty-five minutes. His men were unusually quiet and subdued, in contrast to their normal boisterous behavior. He recalls feeling ashamed, as he had lectured on how to avoid such accidents. He wondered what this would do to his chances of promotion, and discussed this with the sergeant, who tried to cheer him up. During all this time, he recalls no trace of pain, either when he hit the ice slot or during his rescue.

He was strapped onto a stretcher and the helicopter took off. Just then, some forty-five minutes after his fall, a searing pain started in his left shoulder and spread to his neck and chest. He cried out. A crew member gave him a subcutaneous injection of fifteen milligrams of the narcotic morphine from the standard equipment in the emergency kit. By the time they arrived in hospital, he was dozy and the pain had lessened.

In the hospital, it was found that he had a dislocated left shoulder, a broken left collar bone, and serious bruises over his pelvis and upper legs. He was briefly anesthetized, and the shoulder bones were put in their proper place. He was put to bed and slept. Next morning, his shoulder ached all the time and he felt severe stabs of pain if he moved. He was sore all over, and was given painkillers. He felt exhausted and dozed for long periods. When the doctors came on their routine ward round, his pain escalated as they uncovered him and he cried out when they gently touched his shoulder. For the rest of the day, he curled up, moving as little as possible. He wanted no food. When visitors came, he put on his standard act: “Nothing to it,” “Just a bit of a fall,” and “I’ll be out of here in a day or two.” Within himself, he wished they would go away and leave him alone.

This history has two clear epochs. In the first emergency period of forty-five minutes, where survival, escape, and rescue had clear priority, there was injury but no pain. He was mentally clear and supervising his own rescue. Furthermore, he was assessing the situation clearly but blaming himself and fearing for the future. In the second period, when pain began, recovery from the injury had priority. Pain was present and increased with movement or touch. Beyond the presence of pain, his usual character had changed: normally a very active man, he was overwhelmed by lethargy and fatigue; usually a good eater, he had no appetite; habitually gregarious, he disliked company, although verbally he put on a very good act in imitating his old self. Within himself, he displayed the complete syndrome of the best tactics for recovery in people or animals: don’t move, and don’t let anyone else move you, just sleep. Outside himself, he displayed the opposite, for the benefit of other people and for his own image: “I’m all right,” “Soon be out,” “Don’t worry,” “It only hurts when I laugh.”

The Anzio Beachhead

During the winter of 1943–44, Allied troops came to a halt in their advance up Italy on the Gustav line, which included the slaughter point of Monte Cassino. In an attempt to outflank this line, American and British troops landed 50 miles north on the beaches of Anzio in January 1944. They landed successfully on the coastal strip but were trapped when the Germans regrouped in the hills. It took until May 1944 before there was a breakout and Rome was captured. During this time, the Allied troops’ lines hardly moved and they suffered heavy casualties, mainly from persistent artillery fire.

Harry K. Beecher was the medical officer admitting casualties to one of the few hospitals on the beachhead. He was later to become a leader in the new clinical research on pain as professor of anesthesia at Harvard. His concern for humanity reflected that of his ancestor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Every wounded man who could speak was asked the same question: “Are you in pain? Do you want something for it?” All of these men were seriously wounded, as they had already been sent back after first aid in advanced medical posts. Some of these men were in an exalted state, recognizing their near brush with death. Beecher collected the answers and was astonished that 70 percent of the men answered no to both questions. When the war was over, Beecher asked the same questions of an age-matched group of civilian men who had been operated on at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; 70 percent answered yes to both questions.

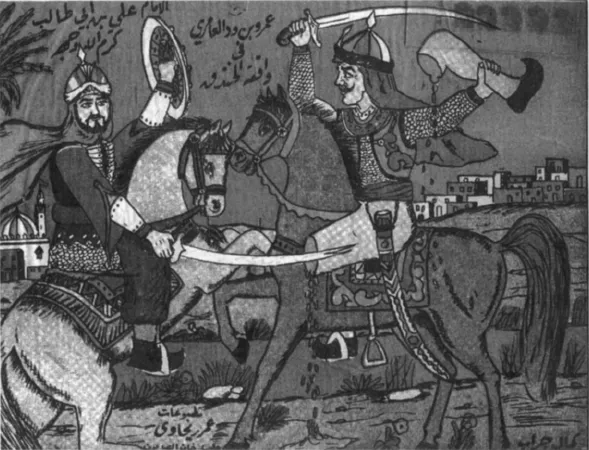

FIGURE 1. Traditional drawing of the battle between the Imam Ali, cousin of Mohamed, and Amr Bin Wid, champion of the enemy host. Amr Bin Wid threw his amputated leg at Imam Ali before being killed. The two-pointed sword called Al-Sahar remains on display in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul.

Beecher reasonably concluded that something about the situation in which the tissue damage was inflicted influenced the amount of pain suffered. Beecher had a theory about what was the crucial difference in the two situations. To be wounded on the Anzio beachhead had a positive biological advantage over not being wounded. This paradoxical statement needs explanation. To be wounded and to reach the hospital at Anzio implied a good chance of evacuation and survival. To remain in the line unwounded implied a serious risk of being killed. Of the 767 men in the American Rangers battalion who attacked in the attempted breakout on January 30, only six returned. Beecher proposed that the men he questioned in Anzio were pain free because they were in an exalted state in the expectation of survival with honor. Therefore, he suggested that there are rare circumstances in which wounding is advantageous, and those wounds are pain free. I doubt this reasoning, but there is no doubt that he observed numbers of seriously wounded men who were not in pain.

The Yom Kippur War

In October 1973, Syria and Egypt attacked Israel and there was a brief, violent war. Dr. Carlen from Canada, Dr. Bill Noordenbos from Holland, and I decided to study a complete sample of Israeli soldiers who had suffered a traumatic amputation during that war. We examined seventy-three amputees from days to months after their injury. Their mean age was twenty-six and ranged from nineteen to forty-five years. This study of the subsequent history of amputees in or out of pain was possible because all Israeli amputees attended a single rehabilitation hospital at Tel Hashomer outside Tel Aviv. On questioning about their first sensation at the time of injury, the great majority clearly described their sensations with neutral words such as “bangs,” “blows,” and “thumps.” Not one described a flash of pain that then died down. These men uniformly expressed their surprise at not feeling pain, often beginning with “Doctor, you won’t believe it but …” A minority had felt pain from the first moment.

With Beecher’s reasoning in mind, we began to inquire about the precise circumstances of their wounding. The scene at Anzio was evidently one of unremitting horror and terror, continuing night and day, with the common soldier adjusting to some passive tactic that he hoped would end in survival. For those of us fortunate enough not to have been in battle, we perhaps imagine that painless injuries could occur only in the heat of combat when the “blood was up” and the victim was engaged in some intense action. But, far from this picture of continuous intensity, the Yom Kippur War was often intermittent, scattered with abrupt short violence. Some of the men had suffered in road accidents as they raced at night with lights out on unfamiliar roads. Some had been asleep in a quiet area when they were hit by an unexpected long-range shell. Others had been hit suddenly by the accidental firing of weapons from their own side. It was evident that painless injury could occur in men who were in no unusual state of mind. The episode appeared to begin precisely upon impact and did not depend on some prior expectation.

Our team, which included fluent Hebrew speakers, very tentatively and diplomatically explored the question whether any of these men greeted their injury as welcome. There was never a hint that anyone adopted the Darwinian approach that being wounded increased their chance of survival. No soldier reported even a fleeting sense of relief that he had escaped alive from the killing fields. Elsewhere, I spoke to a man from another army who had shot off one of his own toes in order to get out of action. He said it hurt badly and immediately. Yet the overwhelming reaction of these seventy-three soldiers to their wound was anger. Surprisingly, it was often directed at themselves: “If only I had not gone into that house” or “If only I had not climbed out of the trench.”

I found the most bizarre story of this kind to come from a man who had lost three fingers from one hand. He had been standing head and shoulders out of a tank turret when he saw an Egyptian wire-guided antitank missile streaking towards him. He dodged down, leaving his hands on the rim of the turret so that he lost his fingers when the missile exploded. He said, “What a fool I was. If I had time to get my head out of the way, I certainly had time to move my hands.” Next to themselves, they blamed officers and, only low on the list, the enemy, who had, after all, really been responsible.

We can leave the topic of emergency painless injury as a fact that we must accept and explain without reverting to ad hoc attempts to classify it as a very special case, as Beecher did, or by using meaningless terms such as shock—the victims had clear minds and were behaving rationally. We have all witnessed one such episode on television. President Ronald Reagan was shot with a 9-mm bullet that entered his chest as he walked from a Washington hotel. He was slammed roughly into his car by the Secret Service men. He and the others in the car did not know he was wounded. He began to feel unwell, and there was a discussion about the possible damage to him when he slumped against the car door. On the anniversary of the shooting, Reagan appeared on a CBS documentary and said, with his wondrous command of English: “I had never been shot before except in the movies. Then you always act as though it hurts. Now I know that does not always happen.”

FIGURE 2. President Ronald Reagan seconds after being shot in the chest with a 9-mm bullet on March 30, 1981, outside a Washington hotel. He felt no pain and did not know he had been shot until he began to feel faint as blood poured into his chest cavity while in the car racing from the scene.

So much for the men’s reports of their immediate sensations. What was their sensory state after some weeks when we saw them? Within twenty-four hours of their amputation, 65 percent experienced a “phantom limb,” a name given by the American Civil War physician Wier-Mitchell to the clear sensation that the missing limb is still present. The remaining 35 percent all felt a phantom limb within a few weeks. Pain in the phantom was experienced by 67 percent, who described it using the words “jabs,” “strong current,” “pins and needles,” “burning,” “knifelike,” “pressure,” “cramps,” “crushing,” and “vicelike.” In addition, many had pain in their stumps, with or without phantom pain as well. On careful examination of the stumps, it was found that every man had at least one area of intensely painful hypersensitivity. At the time these men were examined, in 1973 and 1974, 80 percent had stumps that appeared perfectly healed with no signs of infection. It is particularly sad to report that when this same group of men was examined fifteen years later, even though all signs of infection had gone and all stumps appeared perfectly healed, the pain reports were identical to those we had reported soon after the war.

Now we have three new problems to absorb and explain. What can be the explanation of the common report of no pain at the time of the injury but pain within a day? Second, some of the pains appeared to the victims to be located in a lost limb. And third, some of the pains persisted even when there seemed to be complete healing of the remaining damaged tissue.

Animals with Abrupt Injuries

The major horse race in Britain at the end of the season is the Epsom Derby. To everyone’s surprise, it was won in 1980 by a horse called Henbit, who was far from being the favorite. Half a mile from the end of the race, Henbit was running in the middle of the pack when it stumbled into a hole. The jockey felt and heard a crack. The horse accelerated away from the pack and, with the spectacular perfect gait of a thoroughbred at full gallop, won the race. In the paddock, the jockey leapt off and went to feel the right foreleg. As he suspected, and as was later confirmed by X-ray, the cannon bone, a fine long bone, had been fractured when the horse stumbled. The next day’s newspapers had a headline that read “Gallant Henbit’s career may end.” The horse said nothing but began to limp. With good veterinary care, the fractured cannon bone appeared to knit perfectly, but something changed in the horse. They never got it up to speed again and it retired to stud. Smart horse?

Henbit is not the only horse to have impressed people with its “courage.” In 1632, Sweden’s King Gustav Adolf II was killed at the battle of Lützen in Poland. His horse had a large open gunshot injury in its left shoulder. In spite of this, the horse carried his dead master off the battlefield and walked to the Baltic coast where it died. Awed by this display of “valor,” the Swedes transported king and horse back to Stockholm. The horse, now stuffed, stands today in the stables below the royal palace.

Deer hunters report the effect of rifle shooting at one member of a herd of deer. At the sound of the shot, the entire herd takes off at full speed, aiming for cover. One of the herd has been hit but, with anything short of an immediately lethal injury, it is impossible to identify the wounded animal from the others by its speed, gait, or skill. Long after, the wounded animal may be seen again, curled up, separated from the herd and drowsy.

FIGURE 3. Henbit races away from the pack of horses to win the 1980 Epsom Derby. Henbit had stumbled 150 yards before this picture and had broken the cannon bone in its right foreleg. The picture shows the horse taking its full weight on the leg containing the broken bone.

Dog owners have often seen their gentle domesticated friends suddenly display their hoodlum characters given the chance of a dogfight. Fur flies, canine teeth puncture skin, and chunks of flesh are ripped free. Does the wounded dog stop and surrender? You wish it would. When finally separated from the brawl and taken home, the wounded dog again changes its character. It lies curled up, quiet, sleepy, wants no food, and licks its wounds. Be very cautious in examining the wounds because the dog is likely to yelp and bite you.

The subject of hunting is now under intense scrutiny for many good reasons. A recent study of stags chased and killed by hounds showed that their blood chemistry was grossly abnormal when compared with animals abruptly and humanely slaughtered. The changes were characteristic of intense stress, fatigue, and excessive exercise. Similar but less marked changes are seen in marathon runners who have voluntarily put themselves through a grueling race. The ethical question of cruelty rests on whether anyone is justified in putting an animal through this involuntary stress and not on the unanswerable question of what the animal felt at the moment of death. The fact that a dying soldier on a battlefield may not feel pain in his last moments does not remove the stress from which he suffers, nor does it solve the ethical question of whether his shooting was permissible.

I stress here the similarities between stressed and wounded humans and animals. That does not mean identity between species. There are profound differences. For example, when an old deer is culled by shooting and drops dead, the other members of the herd briefly startle but then continue grazing and ignore the corpse. Deer are evidently not human, but that does not give open permission to kill deer.

Animals and humans in the early stages after abrupt injury may appear to ignore the injury. ...