![]()

Part I

Presenting Agrodiversity

![]()

Chapter 1

Presenting Diversity by Example: Mintima and Bayninan

Mintima, Chimbu, Papua New Guinea MINTIMA IN 1958

I begin the book where I began this sort of work myself, and I will set out what I did there in more detail than I will provide for other areas. The view from the old government rest house at Mintima was spectacular. In the heart of New Guinea lies a range of mountains larger than any other between the Himalaya and the Andes. Rising to more than 4500 m in the east and more than 5000 m in the west, the range contains a series of large intermontane valleys that were not penetrated by westerners until the 1930s but housed more than two million people.1 Mintima, in the western part of the territory of the Naregu tribe of Chimbu, is situated high along the northern slope of one of these valleys. From the spur just below the rest house one could look 100 km east to the triangular limestone mass of Mt. Elimbari, 200 km west to the extinct volcano of Mt. Hagen, and 50 km south across the Wahgi valley to the southern range of Mt. Kubor. Climbing the steep limestone escarpment behind Mintima on a fine day, one could see the ice-worn summit of Mt. Wilhelm, the highest point in the northern chain and the highest mountain in Papua New Guinea, rising above the intervening ridges. The Wahgi valley itself usually was filled with fog in the early mornings, and only as the mist cleared could the river be seen in the middle distance.

Closer at hand, the view often was obscured by clumps of graceful Casuarina oligodon trees, which were planted as seedlings in field plots and allowed to grow for 5 to 15 years. It was also obscured by dense patches of tall grass, some of it wild Miscanthus, and, on wetter ground, semicultivated pit-pit (Saccharum spontaneum). In between these patches were large open sweet potato fields, all dug in a square ditch pattern, and smaller blocks of mixed crops, dominated by sugar cane and bananas. There were also patches of limited-term short grass fallow. In some of the fields, maize, yams, taro, groundnuts, and vegetables were also planted, usually as a first crop after fallow. Further out, beyond fences of sharp casuarina stakes, was an unmanaged land dominated by short grass on the ridges and tall grass in the valleys. Here the family pigs foraged by day, returning at night to houses built along the fences where the women fed them sweet potatoes. The patchwork was at first sight bewildering, and it soon became obvious that the only way to understand it was to map its diversity. This I began to do only a few days after arrival, initially by the most primitive methods, using a compass and counting paces, improving my methods over time. After 1964 I used an accurate map based on low-altitude air photographs and triangulation. The evolution of mapping methods was described in Brookfield (1973).

WORK AT AND AROUND MINTIMA

It was at Mintima that I began the exploration of diverse farming practices that ultimately led to this book. I first went there in 1958 and last visited in 1991. From 1958 until 1970 I was there part of almost every year, but after 1970 I went back only twice. From 1958 to 1965 my work was largely in collaboration with anthropologist Paula Brown, who continued specific work on the Chimbu people right through into the 1990s. We went back there together in 1984, and I went back again alone in 1991. My first interest was in Chimbu farming, Paula’s in Chimbu society. At first, neither of us knew much about either because we had not done this kind of fieldwork before. We chose to go to Chimbu because it had the highest population density of any part of the highlands, but the main models we carried with us were African. Mine were from a limited experience in the field a few years earlier, when I held my first teaching job in South Africa, hers from interpretations of segmentary societies in the anthropological literature. We were looking for shifting cultivation and a tightly structured society, but we found something different.

After a few months we were able to produce a map of land use and land holding over a few square kilometers, understand the organization of group territories and their distribution over a larger area, and write a monograph in which we questioned many of our initial assumptions (Brown and Brookfield 1959). With another year of fieldwork in 1959–60 we were able to enlarge these early interpretations and write a book (Brookfield and Brown 1963) and numerous papers, some of them individual, some of them joint.

My part of the job included walking over fields, recording what was being grown and how; being shown their boundaries and being told about who used them; and mapping this information repeatedly, year after year. My principal information came from a mainly self-selected group of companions of about my own age who enjoyed these hilly days and were not burdened with responsibilities, which then fell to their elders. Two of them accompanied me over the same range of country in 1984, but in 1991 I had to find younger guides, little older than my own son, who was a very small boy when I began in 1958.

By the time the last fieldwork had been done, in 1984, we had good data that spanned more than 25 years on a fast-changing society and its agriculture. These data can be bracketed within a historical and ethnohistorical record that covers most of a century. Change, and rapid change at that, began to command attention as early as 1959, so we were not often tempted to use that deadly ethnographic present to which I referred in the introduction. We knew from a very early stage that the real problem was interpreting the trajectory of events.2 It was uncharted territory and we made mistakes; some of mine are discussed in the last of my papers on Chimbu (Brookfield 1996b). Supposed trends turned out to be false leads. In this chapter I present mainly my conclusions. It may seem as though I knew them all from the outset, but this was not the case.

A LONG AND TURBULENT HISTORY

The 70,000 western Chimbu (or Kuman) occupy land that falls from 2800 m at the upper limit of cultivation to about 1300 m near the edge of the steepening gorge where the south-flowing Chimbu River joins the larger Wahgi River, coming from the west. Today, more than half of the western Chimbu live on land sloping south toward the Wahgi from a major limestone escarpment now called the Porol Range. The others live in the deeply incised upper valley of the Chimbu River north of that range. When the story told here began, and through the first half of the twentieth century, these proportions were reversed.

The area has a long human history; there have been farmers in the central highlands for more than 7000 years. The broad history of their changing use of and impact on the land and its biota has been studied since 1960 by paleobotanists and prehistorians, synthesized by Walker and Flenley (1979), Walker and Hope (1982) and Golson (1982, 1991). The whole reconstruction was succinctly brought together by Haberle (1994). In contrast with Andean farmers, highland New Guinea farmers have domesticated few crops and trees. Almost all their crops are also found in the lowlands, and their farming is essentially lowland agriculture at its altitudinal margin. All the present Chimbu area, except the highest land now cultivated, seems to have been occupied long before the seventeenth century, when the suite of crops used was augmented dramatically by the South American sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), introduced through Indonesia and along trade routes into the mountains. Yielding better than taro and other former staples in the cool mountain climate and more tolerant of poor soils, sweet potato became the dominant crop over very large areas. Because of its tolerance of lower temperatures, sweet potato permitted occupation of land up to 200 m higher than before its introduction. In Chimbu, where there is some of the highest cultivated land in Papua New Guinea, upslope extension of farming continued until early in the twentieth century.

Since the seventeenth century, a range of agricultural practices suited to cultivating the sweet potato evolved in different parts of the highlands. A set of labor-intensive agricultural practices was developed, all including tillage. Those in the western areas involved building large mounds, composted before closure and capable of sustaining cultivation indefinitely on the same land. Everywhere, an explosive growth took place in a possibly older system of indemnifying social relations between individuals and groups mainly by prestations of pigs: live pigs in some areas, killed, butchered, and cooked in others (Feil 1987). By the time rough measurements by professional observers began to be made in the 1950s, up to half of the cultivated sweet potato crop was fed to pigs. This system of competitive exchanges, highly ritualized in different ways in different parts of the highlands, was the outcome of competition between ambitious “big men” who could gain power by manipulating wealth, forcing others to participate. It was also the necessary means of formalizing periods of peace between groups that fought readily. Whatever its longer history, warfare became endemic in the sweet potato period and probably contributed to the association of quasiagnatic subclans and clans into larger tribal groups for common action and defense of territory, pigs, and women3 (Brookfield and Brown 1963; Brookfield 1964; Waddell 1972; Modjeska 1982; Allen and Crittenden 1987; Feil 1987; Brown 1972, 1995).

In legend and possibly also in fact, the mountainous upper Chimbu valley is the homeland of all Chimbu speakers. By the nineteenth century, tribal groups were large and powerful, and there was fierce warfare between them, usually sparked by some minor dispute. Defeated groups were driven off their land, almost all down the Chimbu valley and some ultimately out of it. The tribe that Paula Brown and I began to work among in 1958, the Naregu, was one of the latter. They had been driven into their present habitat, mainly south of the massive limestone escarpment of the Porol Range, by the 1920s. The ethnohistorical record suggests that their forced migration and resettlement, with many fights along the way (within the tribe as well as against others), took place over several decades.

FARMING AND SOCIETY BEFORE THE 1950S

Colonial government and an enforced peace were established in Chimbu between 1933 and 1936. Precolonial skirmishes, battles, and even campaigns, and the resulting forced migrations, still formed the core of most remembered ethnohistory in the 1950s. Diseases, especially the malaria that arises each year in the lower parts of the main valleys, are less remembered than war, but they caused much death. Malaria reduced the ranks of those who settled in the lower-lying areas toward the Wahgi river. There were devastating new outbreaks of epidemic disease in the twentieth century, including a serious epidemic in the 1940s that killed many people. Yet in the upper Chimbu valley, population densities of 150 to 300 per square kilometer were recorded in the 1950s even after a period of sharp population decline.

The high-altitude area of the upper Chimbu valley, almost all above 1800 m, has been agriculturally occupied right through the sweet potato period, since the seventeenth century. Here, sweet potato grows well but slowly, and some of the tropical crops cultivated at lower altitudes are excluded. At least by the twentieth century, land was enclosed permanently within blocks marked by live fences of Cordyline fruticosa. Blocks were cultivated for 6 or 7 to more than 20 years before being planted with fast-growing Casuarina oligodon trees and then opened to the pigs. As soon as land was tilled, small erosion control fences were built across the slope. In some areas the live cordyline hedges were also planted across the slope, building up an accumulation terrace behind them over time (Humphreys and Brookfield 1991). In 1989, coring into the root zone of successive generations of these live hedges on one such terrace in the upper part of the valley, Humphreys (personal communication, 1991) obtained carbonized material dated by radiocarbon methods at around 300 years old.

South of the Porol Range, the environment is more spacious, sloping down from the crest of the escarpment at 2200 m to about 1400 m close to the gorge of the Wahgi River. Most of the area occupied by Naregu after their enforced migration had been only sparsely occupied for at least some time before the late nineteenth century. It was under grassland, mainly cane grass (Miscanthus spp.) on the upper slopes and short grass (Themeda spp. and Imperata cylindrica) on the lower. Bringing their pigs with them, Naregu separated cultivation from the large foraging areas by building impermanent fences of sharp-pointed casuarina stakes. Casuarina trees were planted as a wood-producing fallow crop to supplement the limited natural stands growing in wet areas along the streams descending from the escarpment. Casuarina oligodon grows fast on all but shallow soils and produces a readily splittable, durable wood, used in house and fence construction and as firewood. In addition, it carries root nodules that fix nitrogen. Chimbu is still the main concentration of casuarina planting in the highlands but not the only one. Farmers are well aware that planting this tree improves the soil. In the pollen record it emerges strongly about 1200 years ago, with a major increase since the seventeenth century.

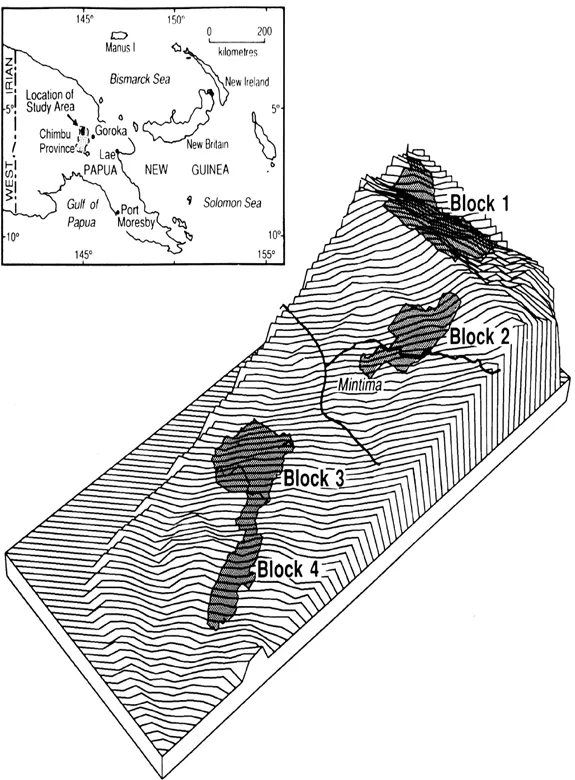

Across the western part of Naregu territory a huge ancient landslip, many thousands of years old, brought down from the escarpment a large quantity of limestone rubble flow that now spreads across the underlying mudstone, sandstone, and shale (figure 1.1). All the upper slopes are steep, and sharp valleys are cut into the mudstone. This mudstone belt is still moving in a series of frequent small landslips, creating areas of wetter land with deep soils around the heads of the streams between the firm, clayey ground on the mudstone ridges and the very friable blocky soils on the rubble flow. These mobile areas often are separated sharply from the undisturbed mudstone ridges by cliffs several meters high. Closer to the Wahgi river, slopes become gentler and landslips fewer. The lowest slopes have only thin soils, and they suffer mineral deficiencies.

There are four distinct types of land below the escarpment: the ancient rubble flows below the escarpment, the higher mudstone ridges that emerge from beneath the flows, the large landslip areas around the headwaters of the south-flowing streams, and the lower southern slopes and valleys. When Naregu first migrated into this area, they settled on the escarpment and on the higher slopes of the rubble flows and mudstone ridges, fencing and cultivating irregularly shaped areas, each around a communal men’s house. The houses of the women and pigs were along the fences some distance away. Later, incorporating an additional clan from among people who had migrated earlier, they spread onto the lower slopes. Ten or 20 years before our work began, all but one of the four constituent clans of modern Naregu had abandoned the escarpment. Only a few men and women have continued to work there, climbing the steep and rocky face of the range. By the late 1920s, before colonial rule brought political stability, the migration was complete, and the area was being filled in. Almost all men’s house sites occupied in 1958 had already been occupied at the time of European irruption in 1933, with the houses rebuilt many times.

Figure 1.1 Block diagram of the Chimbu area showing the location of the four blocks discussed in chapter 1. (Reproduced from Brown, Brookfield, and Grau 1990:26, with permission from th...