CHAPTER 1

SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE WITH IMMIGRANTS AND REFUGEES: AN OVERVIEW

Pallassana R. Balgopal

The purpose of this volume is to examine and develop the role of social workers serving new immigrants and refugees in the United States. New immigrants are considered in this text as those immigrants who entered the United States after 1965. In the past, “old” immigrants were the first groups that settled the country, and “new” immigrants were the Eastern and Southern Europeans arriving since the nineteenth century.

Today’s immigrants represent much greater diversity with regard to country of origin, race and ethnicity, spoken language, religion, and, often, different value systems. In addition to Mexico, today’s arrivals come mostly from Asia, Central and Latin America, and the Caribbean. Where once there were Jewish pushcart peddlers, now there are Korean green grocers, Indian newsstand dealers, Ethiopian and Caribbean bus boys, Mexican and Central American gardeners and farmhands, Vietnamese fishermen, and Nigerian and Pakistani cab drivers. The presence of new immigrants, especially from the Asian countries, is particularly evident in the health-care and high-technology fields. In sum, the American landscape, both urban and rural, now reflects the faces and lifestyles of the new immigrants (Foner 1998).

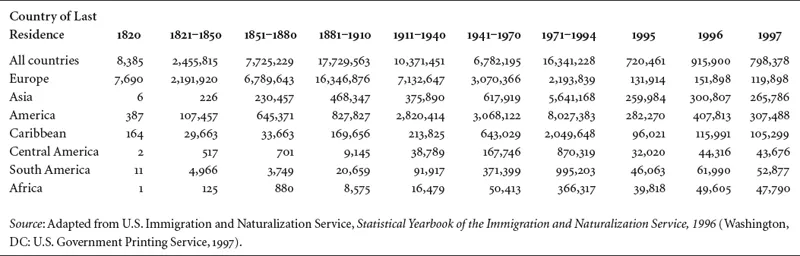

As table 1.1 shows, the composition of the immigrant population changed between the early 1800s and 1990s, making the United States a mosaic of multiculturalism. This drastic change in the immigrants’ profiles was a result of the passage of the Immigration and Nationalities Act of 1965. This act repealed the quotas for each country and instead set 20,000 immigrants per country in the Eastern Hemisphere and established a seven-category preference system based on family unification and skills. In 1976, the immigration act was amended to extend the 20,000-per-country limit to the Western Hemisphere. And in 1980, the Refugee Act was passed, establishing for the first time a permanent and systematic procedure for admitting refugees. Between 1820 and 1940, only a little more than one million immigrants came from Asia, whereas between 1970 and 1997, nearly seven million immigrants were from Asia. The number of immigrants from Mexico, Central and Latin America, and the Caribbean also dramatically increased. The highest number of immigrants continues to come from Mexico. Between 1994 and 1997, 511,763 legal Mexican immigrants were admitted. During this period, the other countries supplying great numbers of immigrants were the Philippines (209,512), China (172,323), Vietnam (163,683), and India (152,589) (U.S. INS 1999). The social welfare needs of these immigrant groups are often different from those of immigrants before 1965, so social work responsibilities have changed as well. In this text we take an ecological perspective, especially in regard to issues concerning direct and indirect practice, community work, policy, cultural diversity, social justice, oppression, populations at risk, and social work values and ethics. We systematically examine and analyze the data concerning new immigrants arriving in the United States after 1965 and explore ideas, concepts, and skills that can help social workers serving immigrant and refugee populations.

The majority of today’s immigrants face many of the same problems that their predecessors encountered, as well as their own special needs, such as a focus on family closeness, on collectivism, and language barriers. For these reasons, social workers should obtain culture-specific knowledge and skills. This book includes a chapter on refugee populations and their needs to which social workers must be able to respond.

UNDERSTANDING RECENT IMMIGRANTS AND REFUGEES

Immigrants

The United States has always been a land of immigrants, with the majority coming from Europe. The first immigrants were Protestants from the northern European continent. Then gradually, more and more Southern and Eastern Europeans began to migrate to the United States, along with people from Africa who were brought over as slaves. Then came immigrants from Asia and Latin America. At first, the Southern and Eastern European immigrants—from Italy, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Armenia, and the former Soviet Union—were shunned by the dominant class of white Protestant Americans. Accordingly, passage of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924 welcomed the Northern and Western Europeans while limiting the entry of the Southern and Eastern Europeans (Greenbaum 1974:424). But the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which replaced the 1924 act, opened the doors to all. Many immigrants of various races, cultures, and countries of origin then entered the United States, and their presence has enhanced the nation. Eventually, acceptance gave way to the entrance, or attempt to enter, of the Asian and Latin American populations, such as Brazilians, Cubans, and Mexicans. Asian immigrants arrived from India, Indochina, China, the Philippines, Korea, and Vietnam, to name a few countries of origin. Table 1.1 describes the change in demographics from the 1800s to 1997. Note that in between 1971 and 1997, the number of Asian, Central and Latin American, and African immigrants greatly increased compared with their number between 1941 and 1970 and the number of European immigrants.

TABLE 1.1

Immigrants Admitted by Region: Fiscal Years 1820–1997

Refugees

Those people who have relocated to the United States for reasons different from those of the immigrants are refugees and asylees. According to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, “a refugee is an alien outside the United States who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her country of nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution” (1997:72). Thus, refugees are persons who flee their country of origin for fear of persecution or oppression due to political, religious, or national reasons or membership in certain social groups. Refugees, however, are often discriminated against and rejected, which makes it difficult for them to become part of U.S. society. Kim’s 1989 study of Southeast Asian refugees between 1975 and 1979 showed that they did not feel accepted and were concerned about their future in the United States. In addition, most of the respondents stated that they did not agree that “I feel that the Americans that I know like me” (p. 93).

The Refugee Act of 1980 (Public Law 96-212, 94 Statute 102) amended both the Immigration and Nationality Act of 19521 and the Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1962.2 Its goal was to create a more uniform basis for providing aid to refugees. The act established specific guidelines for who could be admitted to this country, and when; whether they could bring their spouse and children; and the processes of asylum and deportation. Currently, refugees may work in the United States and may apply for permanent residency after living in this country for one year. They are eligible to receive welfare assistance immediately upon entering, unlike those legal immigrants not considered refugees, who must wait five years before becoming eligible. The number of applications for refugee status filed with the INS rose by 9 percent from 1995 (143,223) to 1996 (155,868). Most of the applicants were from Vietnam (45 percent), the former Soviet Union (25 percent), Bosnia-Herzegovina (12 percent), and Somalia (9 percent). The number of refugees arriving in the United States fell from 98,520 in 1995 to 74,791 in 1996. The main reason for this decline is the smaller number of Vietnamese refugees (U.S. INS 1997).

Asylees are refugees already in the United States when they file for protection. “An asylee is an alien in the United States who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her country of nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution” (U.S. INS 1997:77). Only 10,000 asylees may be accepted as legal permanent residents each year; otherwise they have the same benefits as refugees. U.S. refugee and asylee laws are based on the premise that it is this country’s policy to respond to the urgent needs of persons being persecuted in their countries of origin, that the United States should “provide opportunities for resettlement or voluntary repatriation, as well as necessary transportation and processing” (Miller and Miller 1996:115). In addition, the United States encourages other nations to assist refugees as much as they can. Nonetheless, certain groups of asylees are not readily admitted into the United States. For example, Miller and Miller (1996) reported that Haitians, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans have been restricted from entering the United States despite the threat of persecution in their homelands. In 1985, of the 6,000 applications by Iranians, 63 percent were granted asylum, most of whom were students already in this country. But of 668 Haitian applicants, only 0.5 percent were accepted; of 409 Guatemalan applicants, 1.2 percent were accepted; and of 2,107 Salvadoran applicants, 5 percent were granted asylum. Why are certain nationalities accepted and others are not? Perhaps the Iranian students are likely to complete their degree and to become employed. And perhaps the Haitians have fewer job skills and may be more dependent on the United States’ welfare system. Are ethnicity and race important to determining who is allowed to come to the United States?

Illegal Immigrants

Illegal immigration began slowly at first in the 1870s, increased slightly by the 1920s, and peaked after passage of the Immigration Act of 1965. Currently, in order to enter the United States, one must be a relative of a U.S. citizen or a permanent resident alien or have skills, education, or job experience needed in the United States or be a political refugee. Accordingly, with so many immigrants and so few nonpreference visas available, it often seems easier to enter illegally. Miller and Miller found that “by the mid-1970s, the problem with illegal immigrants was generally considered to be out of control” (1996:27). The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (1997) reported that in October 1996, about 5 million undocumented or illegal immigrants were residing in the United States. Mexico is identified as the leading country of origin, with 2.7 million, or 54 percent, of the illegal immigrants. Indeed, more than 80 percent of illegal immigrants are from countries in the Western Hemisphere.

Illegal immigrants are those people who enter this country without proper documentation or with expired visas or passports. Such immigrants may also include those who enter the United States as migrant workers and then stay beyond their employment dates. In addition, many undocumented Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Haitians are from lower socioeconomic classes with little education (Rumbaut 1994b:613). For people like them, the implications of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) are devastating. Furthermore, the states are prohibited from offering state or local benefits to most illegal immigrants, unless the state law was enacted after “August 22, 1996 (the day the bill was enacted) that explicitly makes illegal aliens eligible for the aid” (Katz 1996:2701). However, a state may provide school lunches to children of illegal immigrants if they are already eligible under that state’s law for free public education. And a state may provide other benefits related to child nutrition and emergency food assistance. Ironically, though, a state may opt not to offer prenatal care to pregnant illegal immigrants.

For example, California’s Proposition 187 denies reproductive services to illegal immigrant women, as well as public education to the children of illegal immigrants. In addition, citizenship is denied to the children of illegal immigrants who are born in the United States, a reversal of the Fourteenth Amendment, which automatically grants citizenship to anyone born in the United States. According to Roberts (1996), there is a rising fear in America that the country will be overrun by darker-skinned people. Because the majority of immigrants, both legal and illegal, entering the United States are not white, limits are being set on who can get prenatal care and education in this nation. As mentioned earlier, Haitians and Mexicans are usually undocumented and usually “darker skinned,” and they seem to be the ones not receiving prenatal care.

The reasons that people flee their country vary, but most of the refugees and asylees who meet the U.S. definition of a refugee or asylee are escaping a communist takeover or some other communist-related regime. For example, large numbers of people from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fled the communist takeover of their countries. The INS reported that between 1981 and 1987, 465,827 refugees from this group were granted asylum and permanent residency. In addition, 38,214 persons from the Soviet Union were granted permanent residency during this same time period. Nicaraguans fled their homeland to escape the civil war against the leftist regime, and Haitians wanted to live in the United States instead of under their right-wing military regime (Portes and Rumbaut 1990:244).

The socioeconomic classes of refugees also have changed through the years. In the early to mid-1950s, the Cuban refugees escaping Fidel Castro’s forces were mainly from the middle and upper classes. In fact, Miller and Miller (1996:2) estimated that “more than 50 percent of its [Cuba’s] doctors and teachers” entered the United States in a two-year period. Eventually, though, most of the Cuban refugees were “boat” people, the “Marielitos,” who were less well educated and from the working class.”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AMERICAN IMMIGRATION

Most of the earliest immigrants to the United States were Anglo-Saxon Protestants, whose attitude toward other immigrants was mixed. On the one hand, the immigrants were needed to develop the new country, but on the other hand, the Protestants did not welcome the impoverished Catholics from Germany, especially when they moved into the Midwest to farm their own lands, thus “taking over” a large piece of the United States.

During this time, these immigrants forced the Native Americans out of their lands and homes. Before Columbus’s arrival in the New World, it is estimated that the population of Native Americans was as large as 12 million. But by 1880, after years of genocide and wars, this number had fallen to about 250,000 (Karger and Stoesz 1994). Lack of immunity to European diseases, displacement from their lands, systematic starvation, widespread killing in war, and cold-blooded murder account for this dramatic drop in the Native American population. Between 1950 and 1990, however, the Native American population again grew by 1.6 million, and by 1994, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population of Native Americans at 2.2 million. In addition to the natural increase are the Census Bureau’s methodological improvements in the way it counts people on reservations in trust lands and Native Alaskan villages and the increase in indigenous people, including mixed Indians and non-Indian parents reporting themselves as “American Indians” (Shinagawa and Jang 1998).

The African slaves were brought to the United States to work on the expanding plantations and vast lands; they were not freed until the late 1800s. They were not permitted to vote until the early 1900s, and not until 1964 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act were they accorded the rights and privileges available to other American citizens. The most obvious difference between the early immigrants and the African slaves is that the latter group had no choice in their immigration. They were brought into this country by force to help in its development but were forbidden, for centuries to come, to reap the rewards for their efforts. In 1790 when the first U.S. census was taken, African Americans numbered about 750,000. By 1860 their number had increased to 4.4 million, but except for 488,000 counted as “freemen” and “freewomen,” the majority were still slaves. By 1992 the African American population had grown to 31.4 million, and “it is projected that by year 2000 this population will be around 35 million” (Shinagawa and Jang 1998:23).

Along with the influx of immigrants, policies were passed to regulate it. Some of the laws were overtly discriminatory,...