![]()

PART ONE

A Revisionist History

Critical race theories’ notions of a revisionist history will be incorporated to explore the multifaceted role for which the contested border region of New Mexico and Texas has had on gang formation and, more importantly, on political inclusion. According to critical race theory scholars Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic:

Revisionist history reexamines America’s historical record, replacing comforting majoritarian interpretations of events with ones that square more accurately with minorities’ experiences. It also offers evidence, sometimes suppressed, in that very record, to support those new interpretations. Revisionist historians often strive to unearth little-known chapters of racial struggle, sometimes in ways that reinforce current reform efforts.1

In graduate school, my dissertation advisor trained me to immerse myself in a setting to learn about social groups. However, my experiences merged into a history-based form of immersion. In doing so, I attempt to be more conscious and aware of the structures that shape interactions. My goal in these next three chapters will be to provide plenty of detail that future researchers can use to follow up on the empirical trail uncovered.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Context for the Origination of Gangs

Double Colonization

In 2006, my family and I moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico, from Denver, Colorado. Las Cruces sits in the Chihuahua desert, so grass or anything green is rare and expensive. Las Cruces is a quiet, laid-back community with amazing food and nice people. The city ranks highly as a location to retire, play youth sports, and experience more days with sunshine. We had a lot of friends, bought roasted green chile, attended our kids’ athletic games and practices, and participated in the social life of the community. We were friends with our neighbors and looked out for the residents living in our community, and they did the same for us. It is, however, one of the economically poorest areas of the country, and it suffers from a tremendous lack of resources. My previous research had been focused on poor neighborhoods within relatively prosperous counties and states. Thus, lower structural resources on a larger scale was a change for thinking about poverty and solutions. Every year, Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count database has ranked the State of New Mexico last or second to last in terms of overall child well-being based on a wide variety of indicators such economics, education, family and community, and health. Southern New Mexico is situated along the U.S.-Mexico border, and if it were a state, analysts argue it would rank as fifty-first. According to the Bureau of the Census, from 1969 to 2015 New Mexico has ranked between 44 and 50 as the poorest state in the country.

For eight years, my wife and I lived, worked, and shared in the struggle to raise our four children. We moved into a new housing development with a lot of military families interspersed in a subdivision surrounded by several trailer parks on a poorer side of town (East Mesa) that, at the time, didn’t have many services, such as stores or restaurants, but it was rapidly growing. The local gas station included a mix of laborers in construction or other types of manual labor. Alcohol was a popular item for purchase, and tattoos were the norm. I fit in perfectly. Most faculty members lived closer to the college campus, about 10–15 minutes away from the freeway. However, the newer housing area offered lower rental prices and more rental units. For my young family, this was the opportunity we dreamed about.

For well over 400 years, a contested tri-cultural relationship developed between Spanish, Native American, and Anglo populations. New Mexico’s race relations made this geographic region historically complex for at least four reasons: double colonization (Spain and United States); a social construction of race beyond the black and white binary (Native American and mestizo); political notions of federal and state citizenship; and a numerical minority majority population that has retained an established presence but has been unable to completely uproot the sociological implications of a marginalized experience. Columbia University anthropologists Charles Wagley and Marvin Harris defined a minority group as 1) experiencing unequal treatment, 2) sharing physical or cultural characteristics, 3) having an ascribed status rather than an identity chosen voluntarily, 4) maintaining a strong sense of group solidarity, and 5) generally marrying within the group.1 Thus, utilizing revisionist history, I have developed an outline of how marginality continued to keep individuals of Mexican descent within a racialized minority group experience.

Native American and Spanish Influences

For at least 10,000 to 12,000 years, Native Americans have lived in the Americas. The earliest people in the Southwest consisted of a variety of pueblo and nomadic groups, including the Anasazi, Mimbres, and later Acoma, Jemez, Hopi, Taos, and Zuñi pueblos, with early archeological sites including Chaco Canyon, Gila Cliff Dwellings, Mesa Verde, and Sky City. Historian Ramón Gutiérrez estimated the Pueblo Indians may have numbered as many as 248,000 at the beginning of the sixteenth century, with seven different languages.2 Pueblo Indians preserved egalitarian societies with tribal differences based on age and personal characteristics. They avoided violence and war as they defied the moral orders of pueblo society. It was only in the past half millennium did Europeans begin exploring North and South America. After Christopher Columbus set sail in 1492, arriving in the region of the Caribbean, many additional European nations soon followed.3 These colonial adventures resulted in large numbers of indigenous deaths as cultures experienced tremendous devastation to their way of life. Historian David Stannard described the conquest of the new world as an American holocaust because violence was a major tool for gaining power.4 England, France, Netherlands, and Spain created empires and colonies in the Americas by 1700.5 For the Spanish, conquest primarily entailed spreading Catholicism and attaining precious resources. Gutiérrez describes how male Spanish conquistadors encountered a variety of pueblo and nomadic Native Americans as they surveyed the region.6 From the beginning, Spanish explorers conflicted with the indigenous populations, whom they viewed as inferior, from Hernán Cortés’s overthrow of Aztecs in 1523 to Don Juan de Oñate’s establishment of the Nuevo Mexico colony in 1598. Sociologist Thomas Hall, who examined social change in the Southwest from 1350–1880, stated, “The name ‘Nuevo Mexico’ reflected a hope that the new area would be another Mexico, full of mines, Indians, and wealth.”7 Despite the ongoing terror, native resistance continued and culminated in the 1680 pueblo revolt against religious leaders and missions that led the Spaniards to temporarily flee the area.8 In addition, nomadic Native Americans inspired fear and threatened the Spaniards’ ability to safely occupy or control the land. 9 For these reasons, Hispano society remained weak and precarious during the Spanish colonial era.10

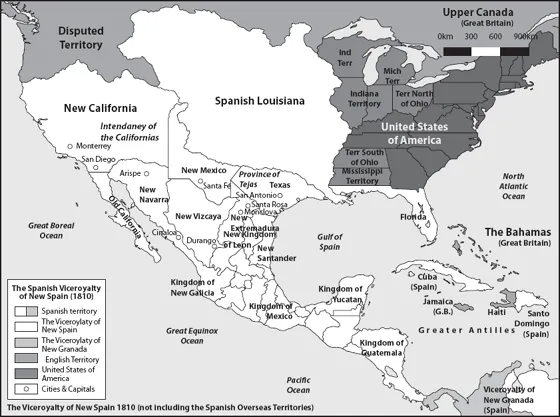

FIGURE 1.1 Viceroyalty of New Spain Map, 1810.

Courtesy of the United State Geological Survey. Image available on the Internet (https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/nps01) and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

Critical race theorist Laura Gómez describes how the colonial experience from Spain brought a five-tier racial hierarchy.11 At the top of the hierarchy were a very small number of residents descending from Spain. This small population intermarried to maintain land and economic control. The second group was known as mulato or mestizo (having mixed Spanish and Native American ancestry). This was the majority of the population, but most of these families used Spanish surnames and attempted to claim more Spanish blood than Native American blood. The third group in this stratification consisted of Native Americans who were kept as servants within elite Spanish homes. Fourth were the pueblo Indians, whose culture, civilization, and community were the most stable and longest lasting before the arrival of the Spanish. Fifth were other nomadic tribes including the Apaches, Comanches, Navajos, and Utes. Gutiérrez reported how the scarcity of Spanish women and abundance of native women resulted in the characterization of New Mexico’s colonists in 1631 as “mestizos, mulattos, and zambohijos.”12 The continued abuse of native women often resulted in their stigmatization and the abandonment of children who were born fair-skinned. The New Mexico form of slavery valued female slaves twice as much as male slaves. Gutiérrez elaborated on the role of race: “Whereas before 1760 racial labels accounted for less than 10 percent of total observations, after 1760 and into the beginning of the nineteenth century, race became the dominant way of defining social status.”13 The two main labels were español (Spaniard) and indio (Indian). The lighter skin color was associated with Spanish blood and an individual’s social status and occupation. Men could possess honor, while shame was an attribute intrinsic to females, which resulted in an insistence on keeping them sheltered. This served to enforce the earliest forms of Spanish patriarchy.

Mexico’s Independence

In 1820, the population in New Mexico was estimated to be 38,359, of which 74 percent (28,436) were Spanish and 26 percent (9,923) were Native American.14 During the war for Mexican independence in 1821, the original small number of Anglos attempted to coexist with the Spanish elite by living, marrying, and working together. This produced a society in which racial power-sharing was evident. The numerical minority of Anglos existed in a social world where Spanish language, jury involvement, and police representation of Hispanos was fully evident.15 Racial labels were legally abolished in favor of nationality labels of ciudadano, mexicano, or “no mention.”16 Sociologist Thomas Hall stated that there was an increase of Native American attacks during the 1830s and 1840s, possibly due to the increased trade in alcohol and guns.17 Mexican governors in the states of Chihuahua and Sonora enacted a policy of Apache extermination by offering money for scalps. In 1843, residents established the Doña Ana Bend Colony Grant, but due to fears of Apache attacks the area remained sparsely populated with possibly as few as 47 families and 22 single men.18 The city of Las Cruces would later develop in this area. The other regions of southern New Mexico, including Grant, Luna, and Hidalgo Counties, also remained sparsely populated.

FIGURE 1.2 U.S. Territorial Acquisitions Map.

Source: http://www.thomaslegion.net/americancivilwar/mexicancessionlessonstudentsandkids.html.

The United States Influence

As the United States used the U.S.-Mexican War (1846–1848) to seize the entire Southwest, nearly half of what was then Mexico, one researcher described the war as defining white, Anglo-Saxon supremacy.19 While the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted the mestizo population a white identity for having one drop of Spanish blood, this did not result in equal treatment.20 Hall reported that New Mexico differed from California and Texas by three important distinctions: a large Mexican and Native American population that had been established for centuries, a slower population growth, and the only non-elite organized rebellion. New Mexico was the most populated section of the region.21 It was reported that there were at least 60,000 residents living in New Mexico compared to 7,500 in California, 5,000 in Texas, and 1,000 in Arizona.22 Most of these residents (91 percent) were Nuevomexicanos with Spanish names, 5 percent were Native American, and less than 3 percent were Anglo American.23 The Rio Grande became the separating line between Mexico and the United States, in the process splitting the land of the original El Paso del Norte into what is now known as El Paso in the United States and Ciudad Juárez in Mexico.24 Gómez described how Mexicans living in the area were given three options: move south of the newly created U.S.-Mexico border, keep their homes but retain Mexican citizenship, or keep their homes and after one year acquire U.S. federal citizenship.25 Federal citizenship granted protection of the Constitution but did not offer political right...