eBook - ePub

Collaborative Risk Mitigation Through Construction Planning and Scheduling

Risk Doesn't have to be a Four Letter Word

- 165 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Collaborative Risk Mitigation Through Construction Planning and Scheduling

Risk Doesn't have to be a Four Letter Word

About this book

In the complex, cash-strapped, high pressure world of modern construction, what do you do when something goes wrong? This work looks beyond the best-case scenario to give project managers, contractors, architects and engineers the tools to prepare effectively for the unexpected.

Based on the author's more than thirty-five years of construction management experience, the book shows how to proactively mitigate a schedule. It opens with case studies of real life construction mitigation, and goes on to examine the conceptual aspects of anticipating risks and making contingency plans, technical aspects of scheduling, and essential role of communication in change management.

Working on the principle that no major project can ever quite go to plan and that "it's not how you start, it's how you finish," Collaborative Risk Mitigation is the ideal complement to traditional scheduling textbooks.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Collaborative Risk Mitigation Through Construction Planning and Scheduling by Lana Kay Coble in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Has It Ever Gone as Planned?

After 38 years of direct and indirect scheduling practice, the author has yet to see a project completed exactly as the originally prescribed plan. One observed common fallacy between all project practitioners is clinging to the premise that they have a perfect plan and further adjustments are not required. This perspective is an illusion that will slow the process in recognizing risk factors and changing circumstances, which ultimately minimizes the team’s ability to respond effectively. A real-life example of this mentality is demonstrated when the schedule becomes “wallpaper.” How many times have you walked into a construction trailer, seen the schedule attached to the wall, and peeled the corner of the schedule back to find the wall faded behind it? This condition is almost always an indicator of the practitioners viewing the schedule as static and nonresponsive to changing conditions.

The perfect plan is an illusion, Change is inevitable.

1.1. Change Is the Only Constant

As in life, change is inevitable and will occur during the life of a project. Success is measured by how the team adapts to the dynamic environment and the schedule reflects the time changes associated with change response. The organic nature of the schedule, whereby it consistently evolves due to changing conditions, is essential for project practitioners to accept. Change can appear in many forms: staff turnover, owner-driven scope change, local regulation requirements, environmental impacts, and end user’s inability to conceptualize two-dimensional drawings. Actual experienced examples of these types of conditions are as follows:

Project Success is Hinged on the Teams Ability to Adapt

- Staff turnover and owner-driven changes: The week prior to scheduled construction groundbreaking, a key leadership position of the owner’s team was changed (Director of Facilities and Construction) which resulted in re-evaluation of the projects program to meet the end user’s needs. The design and construction team were placed on hold for three months during this evaluation period. Upon completion of the program review, the decision was made to commence construction immediately and add additional floors to the project. This change in direction impacted the entire team of architects, engineers, and contractor. Actual details of this schedule impact are discussed in the chapter for case study 1.

- Local regulation requirements: During the final week of inspections on a five-story high school, the mechanical inspector determines that a potential fall risk could occur when a heating, ventilation, and sir conditioning (HVAC) unit will be serviced on the roof. With one week left to go in the project, that inspector decides that a final certificate of occupancy will not be granted until permanent handrails are installed. In this particular case, the team had built contingency time into the schedule so there was no impact to the schools opening day.

- Environmental impacts: A school of nursing building, located in the Texas Medical Center on a highly congested intersection, was in the construction process when an optic fiber cable was discovered inside the building line of the foundation. The cabling wasn’t identified on the plans nor was it labeled as to whom it belonged to. Since the impact of critical care services could be at risk, by cutting the line, a 2-week delay occurred to the foundation while the project team determined which institution owned the line. As this was early in the project, there were multiple opportunities to mitigate the delay and finish the project on time.

- End user’s ability to understand two-dimensional drawings resulting in nonalignment of expectations: This type of nonalignment event probably occurs most often across all types of projects because end users are typically not well-versed in construction application. To illustrate this situation, a recently constructed five-story high school was designed with structural concrete frame and floors. The architect designed the floors to be polished concrete and the final appearance of the floor wasn’t communicated clearly enough to the end user. When the building was almost ready to open, the end user didn’t like the fact that there were natural cracks in the polished concrete, a condition created by the nature of elevated structural concrete. This late discovery was the result of not clearly aligning expectations of the finishes, which could have been avoided early in the project. As construction practitioners, it is critical that this type of knowledge is not taken for granted, and the end product is visualized through the end user’s perspective.

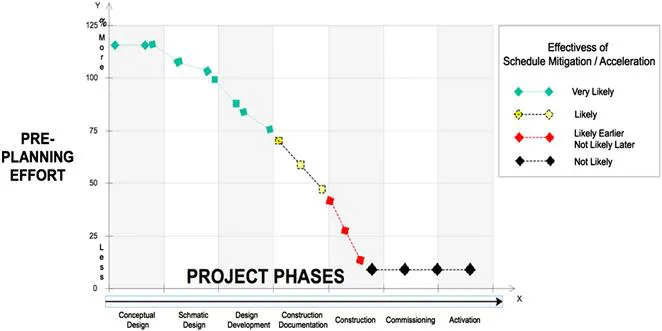

As change is a given, it is equally important to understand that the impact of change is less when incurred earlier in the project. Figure 1 illustrates the impact on cost relative to the effectiveness of change during the lifecycle of a commercial construction project. Most practitioners are familiar with this illustration; however, the aspect of time is seldom addressed.

Figure 1: Effectiveness of Change in the Form of Schedule Mitigation or Acceleration during the Life of a Project.

In reality, time follows the “Effectiveness of Change” path. The “less-more” axis becomes effort. When greater effort is applied earlier in the project (Predesign and Schematic Design), probability increases for the creation of time contingencies and minimizing risk. The primary lesson learned with regard to change is anticipate as much as you can, as early as you can, so you have reserve time to utilize for those unanticipated changes.

1.2. Forms of Risk

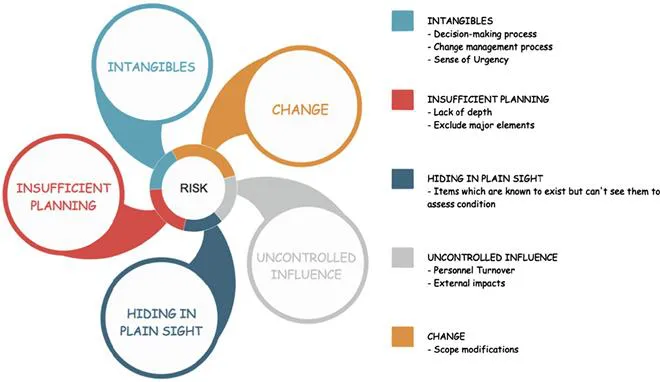

While change is considered the most common bearer of RISK, other aspects of project management can impact a schedule such as intangible elements, insufficient planning, uncontrolled project influence, and elements that are hiding in plain sight (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Forms of Project Risk.

The illustration in Figure 2 above, represents high-risk aspects which can impact a project timetable and share the trait of potential change. Intangibles are nonphysical states or processes which can impact time such as an attitude lacking in a sense of urgency or inefficient decision-making processes. The experienced practitioner knows that change management and decision-making processes can vary greatly from institution to institution. Practitioner firms are not excluded from consideration when evaluating the effectiveness of these processes. As an example, some owners may take longer to finalize change orders due to increased number of levels of approval in the process. Another intangible risk can be represented by a practitioner team which is deflated due to excessive changes or obstacles encountered in the project’s execution. Sustained frustration can lead to lack of productivity which can erode time from the schedule. Intangibles can be characterized as subtle time-killers and as such can be difficult to identify and correct. Oftentimes, the intangible elements are those that can be the most destructive to time contingencies or activity durations because of the nonphysical nature. In preparing a schedule, these items are difficult to quantify on a time scale and oftentimes ignored or underestimated. Insufficient planning is a tough risk factor to evaluate by most execution teams since practitioners tend to plan based upon past experience. While the approach of utilizing past experience and lessons learned is considered as a positive, it can be limited in not providing enough depth. A good rule of thumb for the level of depth to apply in the planning effort is to equal the perceived element of risk with the construction component or activity, i.e., the more risk, the greater the planning. An example of matching risk with the level of planning was the construction of a steel crown, aka “tiara,” on the top of a 25-story hospital, where the structure was elevated 40 feet above the roof and 25 feet beyond the face of the building. The unusual nonrectilinear shape of the tiara in conjunction with the size and location of the steel members made the building element uniquely difficult to construct. As a result, the designers, fabricators, and installers dedicated approximately 4–5 months of collaborative planning in an effort to ensure an efficient schedule and safe installation.

Effort of Planning should be equivalent to the level of Risk

Uncontrolled influence can appear in many forms and can originate either externally or internally. One of the most common manifestations of uncontrollable impact to construction is catastrophic weather events. Tornadoes and hurricanes can occur with relatively short notice, preventing preparations to protect the construction site from damage, unless of course your project consists of interior scope only. The key word in identifying this type of risks is “uncontrollable,” which can manifest from employee turnover or as contractual language defines the term Force Majeure. The Latin derivation of the term is superior force beyond the control of all parties and instances including crime, war, weather, and labor strikes. The last and sneakiest construction risk element are those issues that are hiding in plain sight. These risks are known to exist, but their condition cannot be assessed due to their lack of accessibility. Two conditions of the most common construction examples are in the form of inaccurate “as built” drawings for a remodeling project or incorrect depiction of underground utilities. In both conditions, the practitioners believe they know what exists, but in reality, the final determination cannot be achieved until the existing conditions are uncovered. One of the most common mistakes on construction projects is failure to uncover existing utilities early enough in the schedule to allow for potential correction of existing conditions. One such condition occurred with an existing sanitary sewer line in a congested urban setting, where two independent agencies had modified the lines flow. Upon investigation, it was determined that the last agency (“B”) who modified the line had failed to notify the other agency (“A”) of the change. The civil design professionals utilized agency A’s as-built drawings, which was typical practice. In this instance, the existing sewage system was stagnant with the manholes holding 6′ depth of waste. The contractor had field verified the existing utilities early in the project and there was adequate time to redesign the utility lines to accommodate sufficient flow for the sanitary sewer system. This situation occurs more frequently than expected and has shaped the risk approach of “what you cannot see, will hurt you.” The purpose of this phrase is to accentuate the importance of exposing nonvisible conditions earlier in the schedule to allow for time contingencies.

With all the forms of change illustrated above, it could be considered common sense to focus construction planning on elements of risk. Statistically speaking, however, the higher risk elements have the highest probability for change, therefore time spent on contingency plans may yield the best schedule results. The conservation of time, especially in the early stages of a project, is critical to schedule management. In technical terms, this time contingency is referred to as float. In practical terms, it is best to think of float as a time contingency, which can be applied for mitigation of the risk factors in Figure 2. Team success is differentiated by how we manage risk and solve problems. How we respond to change defines us as practitioners. And regardless of the practitioners technical scheduling prowess, everyone relates to risk. Just as it takes multiple perspectives to create a more complete understanding, it is key to realize involving all team members in the quest to identify and assess project risk will contribute to a better execution plan. This collective, risk-focused approach shifts away from the old school paradigm of scheduling as only a technical exercise in illustrating construction activities. The technical aspect of scheduling is still important but the focus on risk allows for expansion of content. Acceptance of this method facilitates understanding high-risk activities from all members of the project team during all phases of the project (i.e., predesign, design, budgeting, procurement, permitting, construction, commissioning, and end user activation) and creates a comprehensive plan. These are the reasons why this book focuses on the art of managing risk in construction.

Responsiveness to changing conditions after the creation of the baseline schedule is a key characteristic of optimized schedules. With all of the potential for change, as identified earlier in this chapter, thought should be given to how the baseline schedule is organized. This approach is often neglected by practitioners during the development of the original schedule due to a myopic focus on content. Those who do consider the organizational impact generally limit their layout to a work breakdown structure (WBS). Specifically, the schedule should be created where activity adaptations can be easily implemented during the life of the project to reflect change. This planning should consider the constructability sequencing of the project. An example of this approach was implemented on a university classroom and administration building which required all exterior walls to be replaced due to leaks. The situation was compounded as the building was in the shape of a “piano” and had approximately 12 different elevations. Other constraints on the building process was the building had to remain operational during construction. Early in the planning, it was apparent that the glazing subcontractor may have worker staffing issues which could result in fluctuations of productivity. Based upon these high-risk levels, each elevation was planned as an independent work sequence. Once the activities have been developed, the schedule was organized in a similar fashion, by elevation. Within two weeks of starting actual construction, the subcontractor confirmed that worker availability had changed and required re-sequencing of the elevations. Due to the anticipation of this potential change, the team was able to adapt the schedule within a short period of time and still met the overall delivery mandate. There were additional changes invoked by the university to accommodate off-cycle occupancy needs. The approach of anticipating change as it reflects to the organizational structure of the schedule facilitated a “win-win” scenario for the entire team.

The last critical aspect of schedule risk management involves understanding the difference between contingency and mitigation planning. Merriam-Webster dictionary (2017) defines a contingency plan as “a plan that can be followed if an original plan is not possible.” Mitigation (Merriam-Webster, 2017) is defined as lessening the severity of damage or loss. In the context of time, contingency implies that it is prepared prior to actual impact to the baseline schedule, where mitigation seems to apply an ad hoc approach to minimize delay impacts. In terms of the final outcome, mitigation assesses the results of the contingency plan. This distinction is important as the higher risk implementation processes should have contingency planning prepared prior to actual execution. Mitigation becomes more of an immediate adjustment approach to managing time delays.

In summary, with every project, there is always RISK. The sources of risk can vary from internal to external, forces of nature, labor, economics, politics, project leadership, delivery method, and so on. The constant in project execution is change. Risk planning is necessary once the baseline schedule is prepared to increase the percentage of successful deadline delivery. While many of the concepts described can be correlated to common sense thinking, the point is that practitioners can increase success by adopting a risk assessment approach. In order to apply this paradigm, collaboration and risk assessment should be at the forefront of all planning efforts.

Chapter 2

Who Benefits from Planning and How?

To grasp the extent of benefits from planning, the distinction between planning and scheduling must be understood. There are some key distinctions that differentiate the two efforts. The first of which is that any stakeholder can participate in planning, but scheduling is limited to practitioners who create the schedule utilizing a software platform. Knowledge of the construction process is not required during planning, where it is mandatory during scheduling operations. Planning addressed the question of “Who?,” “What?,” “Where?,” and “How?” while scheduling answers for “When?”. Planning is generally framed from a macroscopic perspective vs the microscopic characterization of scheduling. The one common aspect of both planning and scheduling is RISK. These differentiators are presented in a broad perspective. The following paragraphs will delve into the smaller, more specific elements of planning and scheduling.

2.1. Planning

The most significant aspect of planning is that it is inclusive of all stakeholders and their knowledge of construction methodology does not prohibit them from participation. The members of a team can range from owner, designers, general and subcontractors, utility providers, neighborhood associations, end users, maintenance personnel, and regulating authorities. The key parameter is that each person understands or represents some element of risk to the project. The significant questions become “What is a risk to the project?” and “What is the worst case scenario?”. To frame your thinking in terms of risk, below are examples from differing team member perspectives (Table 1).

Planning answers Who, What, Where, and How?

Table 1: Stakeholders’ Potential Risk.

Stakeholder | Potential Risk Questions |

|---|---|

Owner |

|

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Has It Ever Gone As Planned?

- Chapter 2 Who Benefits from Planning and How?

- Chapter 3 Real Construction Mitigation Case Studies

- Chapter 4 Risk Management Matrix

- Chapter 5 Communicating the Project Schedule and Change Management

- Chapter 6 Contingency Planning

- Chapter 7 Implementing Mitigation Measures Through Technological Application of the Computer Scheduling Software

- Chapter 8 Did Your Planning Meet the Desired Deadline?

- Appendix

- Definitions

- References

- List of Figures & Tables

- Index