![]()

1 ART FOR THE STATE

Realist art is the art of battle: it battles against false views of reality and impulses which subvert man’s real interests. It makes correct views possible and reinforces productive impulses.

Bertolt Brecht1

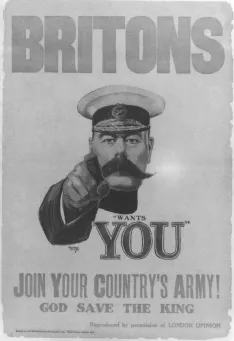

Nations have always requisitioned and utilized artworks. If anything, this process proliferated in the twentieth century, when art was widely adopted for propaganda purposes and those who produced it were strictly controlled by totalitarian states. It was the Soviet Union that initially kept the tightest control on cultural output and defined the needs of the state. The influence of both the Soviet Union and China was behind the development of Socialist Realist art in North Korea. In most circumstances, art for the state can be characterized as being essentially large-scale, dramatic and message-laden (illus. 2).

It is not only the production of artistic works that has been determined by totalitarian regimes. Control also extends to the destruction of works of art regarded as inappropriate.2 In Nazi Germany, art eschewed by the state, Entartete Art, was ridiculed and disposed of. Later in the century, hordes of marauding young Red Guards in the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–76) terrorized the population by bursting into their houses and smashing antiquities and family heirlooms in order to carry out Chairman Mao’s orders to destroy the ‘Four Olds’. In more recent decades a succession of images of deposed Communist autocrats have been destroyed after a change of regime, while in Budapest they have been collected in a park for unwanted state sculpture. The most dramatic recent instance of destruction is perhaps the blowing up by the Taliban of the large Buddha statues at Bamiyan in Afghanistan in 2001. The widely reported toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 2003 demonstrates the tremendous impact that popular destruction of a work of art prescribed by the state can have (illus. 3).

2 Alfred Leete, Your Country Needs You!, 1914, design for a recruitment poster.

3 Saddam Hussein being toppled.

HISTORICAL PRECEDENTS

There are many historical precedents for the kind of buildings, monuments and works of art produced in North Korea under the Kim regime, some of which may have been known to the artists and policy-makers and some not. It is doubtful, for example, that Kim Il-sung (1912–94) would have been conscious of the fact that, when encouraging his subjects to think of North Korea as Paradise on earth (illus. 1), he was following in the footsteps of Augustus Caesar in the first century BC. It has been suggested that, by using a new visual imagery, Augustus created a new mythology of Rome:

Built on relatively simple foundations, the myth perpetuated itself and transcended the realities of everyday life to project onto future generations the impression that they lived in the best of all possible worlds in the best of all times.3

The Roman Empire was the major model for public art, and the use of the triumphal arch to demonstrate the glory and triumph of the regime dates from this time (illus. 4, 5 and 6).

4 G. B. Piranesi, Arch of Severus and Caracalla in the Roman Forum, 1756, etching.

5 Jean-François Chalgrin, Arc de Triomphe, Paris, 1806–36.

6 Mansudae Studio, Arch of Triumph, Pyongyang, 1982.

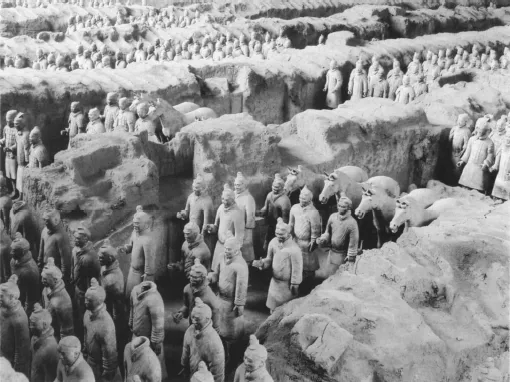

7 Pit containing thousands of terracotta warriors guarding the tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi, who died in 221 BC, at Lintong outside Xi’an.

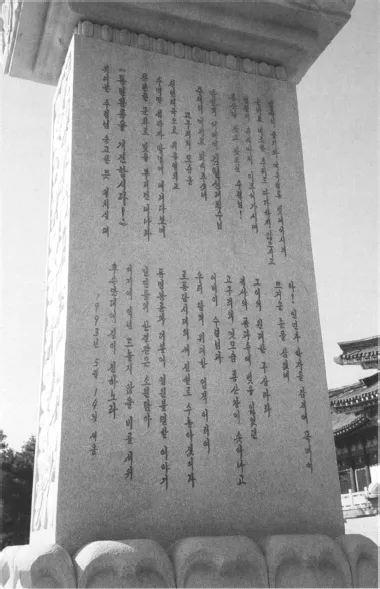

Kim is much more likely to have been aware of the first emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi (256–221 BC), who was notorious not only for unifying China, its currency, weights and measures and written script, but also for his burning of the books of Confucianism in his megalomaniac desire to control the hearts and minds of his subjects, both during his lifetime and after his death (illus. 7). Also like Kim, he travelled around his country erecting stelae marking the places he had visited and listing his achievements, as if to say, ‘look at me and remember’ (illus. 8). For example, part of an inscription on a tower at Mount Langya reads:

Great are the Emperor’s achievements . . .

He works day and night without rest;

He defines the laws, leaving nothing in doubt,

Making known what is forbidden.4

Kim would definitely have known of another great Chinese emperor, Qianlong (r. 1736–95), who also carried out what has been called a ‘literary inquisition’.5 In his attempt to compile the Siku Quanshu, a great encyclopaedia of written material on all subjects, Qianlong censored many works he disapproved of. He also had a tendency to deface great works of art with long inscriptions and colophons in his own calligraphy or large imperial seals to show his ownership and control of the works. Although he was following traditional practice, he carried it to extremes (illus. 9).6 Qianlong’s confidence in the superiority of his empire over all outside it is also expressed in his rebuttal of George, 1st Earl Macartney’s embassy in search of a trade agreement in 1793:

| 8 Kim ll-sung’s calligraphy inscribed on a stone stele in front of the tomb at Chinpari, south-east of Pyongyang, said to be of Tongmyong, first king of the Koguryo Kingdom. The date of his birth is given as 298 BC in North Korea and 37 BC in South Korea. |

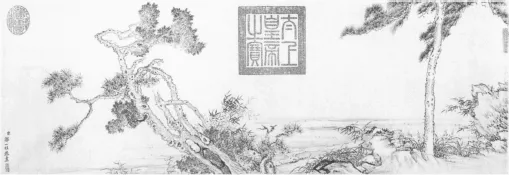

9 Painting by Zou Yigui (1686–1772) created to accommodate the large red seal of the Chinese Emperor Qianlong (1736–95) reading: ‘Treasure of the Most Exalted Emperor’, one of many stamped on to the famous Admonitions of the Court Instructress painting attributed to Gu Kaizhi (c. 344–c. 406).

The virtue and power of the celestial dynasty has penetrated far to the myriad kingdoms, which have come to render homage and so all kinds of precious things have been collected here. Nevertheless we have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your country’s manufactures.7

This sounds remarkably similar to Kim Il-sung’s philosophy of Juche or ‘Self-Reliance’.

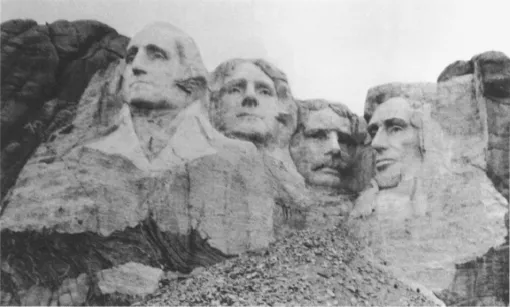

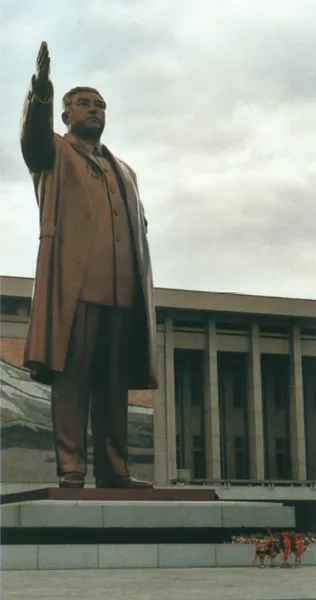

Kim’s predilection for large sculptures of himself (more than 500 had been recorded by 1980)8 follows in a long tradition of sculptures of Great Leaders all over the world, whether in totalitarian states or not (illus. 10). The difference in North Korea is that there are relatively few sculptures of anyone else. Monumental public sculpture is not, of course, a tradition that was common in the Far East before the arrival of Western customs, and it is clear that the concept of Great Leader images was taken from the West via the Soviet Union and China. In the nineteenth century many great men were portrayed in the West in the open air as instructional tools for the ordinary people. In Paris there reached a point of what has been called ‘statuomania’ in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when 150 statues were erected, but after the First World War statues in marble and bronze lost their popularity, apart from the special case of war memorials.9 In Russia, after the Revolution of 1917, Lenin proposed putting up monuments of suitable great people in major cities, particularly as a way of educating soldiers. In fact, it was the Soviet Union that carried on the tradition of public statuary, developing great symbolic monuments to workers and peasants, as well as commissioning huge depictions of Lenin and Stalin. It was these that formed the prototype for the Kim ‘statuomania’ (illus. 11).

10 American Great Leaders over 18 metres high, carved out of the rock at Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, from 1927 onwards.

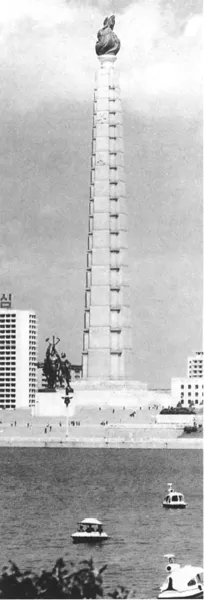

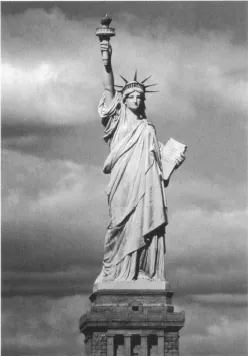

Capital cities and their grand layouts have also played a major role in expressing the power of many differing regimes throughout history, and Pyongyang is no exception. Its almost total destruction during the Korean War (1950–53) meant that it could be planned afresh. Not only the layout, but also government buildings, stadiums, statues and monuments attest to a very high degree of central control. There is sometimes a curious mixture of influences from Western monuments, transferred through Socialist Realist Soviet and Chinese works, to a hybrid North Korean monumentalism, although this would be denied in the name of Juche. Towers, columns and obelisks have been associated with glorifying the state since ancient Egyptian times, and the Juche Tower (illus. 12), while built as the flaming beacon of Juche, showing Kim Il-sung’s unique Juche thought shining out over the world, in fact has a flame feature in common with both the Monument (to the Great Fire of 1666) in London and the Statue of Liberty in New York (illus. 13, 14).

| 11 Mansudae Studio, Statue of Kim ll-sung, 1972, bronze originally gilded but later removed; 20 metres high, Mansudae Hill, overlooking Pyongyang. |

12 Mansudae Studio, Juche Tower, 1972, Pyongyang. At 170 metres it is the highest stone tower in the world. The electric flame on the top symbolizes Juche Thought.

13 Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, New York, 1886, stone, also holds a flaming torch, symbol of Liberty.

14 Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren, The Monument, built between 1671 and 1677 to commemorate the Great Fire of London in 1666. It is 61.57 metres high and also topped by a flame.

ART FOR THE STATE IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

In the twentieth century, Fascist Italy and Germany as well as the Communist Soviet Union and China developed the apparatus of producing art for the state. It was perhaps in the National Pavilions at the Paris International Exhibition of 1937 that the art of some of these rival states could be compared best. International exhibitions had been organized since the first one in London in 1851 and were an ideal way of showing how art reflected the power of the states participating in and organizing them. In 1937 Paris used the exhibition to glorify the regime of its first Socialist prime ...