![]()

PART ONE

FRAME AND IMAGE

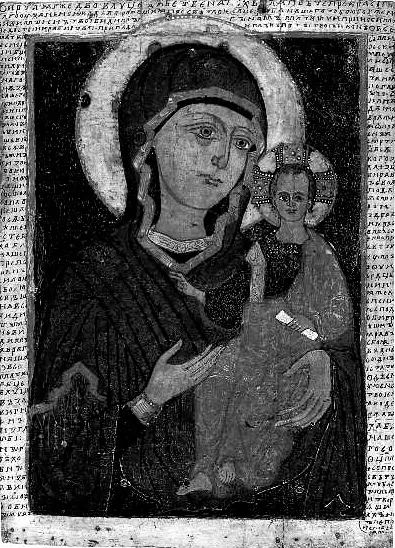

1 Vladimir Mother of God. c. 1131, with later restorations. Made in Constantinople. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Symbolic Unity

Earth! Thou comest close to Heaven through God’s grace. Heaven! Through God’s grace art thou reconciled with Earth.

Dimitriy Rostovsky1

Ark and Niche

The frame of a medieval icon, whether of the seventh century or the twelfth, is a border between the sacred and the worldly that brings to mind the severe wall of a Byzantine church, a safe stronghold that protects the space of the church from our world that has gone astray. This is not accidental. Byzantium intended the icon to be a complex sign system with several layers of perception and comprehension. The chief peculiarity of this system is that all these layers formed an unbreakable symbolic unity and were strictly subordinated to the theological and liturgical context. For that reason the frame of the icon is the initial level at which one perceives the central ‘countenance’; it ‘highlights’ holiness, while always deliberately implying distance and presuming the concealment of that which lies behind it, not allowing one to approach and scrutinize the object. The object has to be taken as what it is and not what it might seem to be. But the light also illuminates the person standing before the object. Thus the light is capable of giving out illumination: it potentially links the object and the subject of cognition, since it can be related to that ‘light’ which in the metaphysical writings of Dionysios the Pseudo-Areopagite is understood to be the unmediated divine energy.2 The glittering precious stones and gold of the framing of the icon both receive and give forth a mysterious light. The adornments of an icon are human gifts to God, but their mystical highlights are elucidated by invisible dimensions. For that reason the icon frame and the depiction are for the religious consciousness indissolubly joined. The frame strives to make plain its fusion with symbol – the representation of God or a saint; in its turn this representation strives to coincide with its meaning. This is the meaning of the icon.

2 Detail of the ark.

In the medieval icon, frame and representation have a single material basis. The icon is painted on one or more boards, joined together by special fastenings. The margins of an icon – its ‘material frame’ – come into being as a result of a hollow being cut into the middle of the icon, on which the image of Christ, the Mother of God or a saint is painted. In the Russian language this icon frame was given a special name: ‘ark’ (kovcheg). Here is how one commentator defined its profound basis in dogma:

3 Portrait of an unknown person, 1st century AD. British Museum, London.

Within icons there is nothing accidental. Even the ark – the raised frame, containing the representation in its hollow – has a dogmatic foundation: the human being, located in the frames of space and time, of earthly existence, has the opportunity to contemplate the heavenly and the divine not directly, not straightforwardly, but only when it is revealed by God as if from the depths. The light of Divine Revelation in heavenly phenomena as it were moves aside the frames of earthly existence and shines with a splendid radiance, surpassing all earthly things, from out of a mysterious distance.3

4 Heron and unidentified military god, c. AD 200. Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels.

Hence it is clear that the ark of an icon is a definite means of linking the central image with surrounding space. Just such a construction characterizes the major holy object of early Rus’, the icon of the Virgin Eleousa (Vladimir Mother of God), brought from Constantinople in the early twelfth century (illus. 1). In the central recessed portion of the board on the front of the icon the image of the Mother of God with the infant Christ is represented, separated from the surrounding space by broad margins, that is to say the frame (illus. 2). Detailed investigations have shown that in its present form this icon is a complex construction of the remains of painting and structural additions of various periods. Thus the frame of the icon (its margin) has changed several times depending on the function of the image. Originally the icon, evidently, was portable. Subsequently it was trimmed down and battens were added to the frame, widening the margins. The picture was repainted many times. In the fifteenth century a representation of the Hetimasia (Prepared Throne) was accommodated on the back of the board. In this way over the centuries this notable icon underwent several interferences, was decorated with a variety of metal casings and additions, and was placed in surrounding structures – cases and iconostases. As its restorer and investigator Alexander Anisimov noted, ‘In its present form the Vladimir icon is no longer a painting that is the work of one hand and brush. Almost every century from the 13th to the 20th has left its traces in its complex texture.’4 All these additions, scars and marks are no less than ‘the capricious elements of memory’, that is to say the historical traces of the connection of the image and its frame with surrounding historical reality. But the chief peculiarity of this famous icon from our point of view – the presence of an ark – remained unchanged. How then did it arise and what did it mean? We just know one thing: ancient classical and Old Testament traditions stood behind it.

5 Christ in Glory, 7th century. Monastery of St Catherine on Sinai.

Prehistoric cave art, of course, had no knowledge of any frame. An early artist’s drawings even cut into one another: in his consciousness they were not marked off from surrounding space and ‘lived’ in different spatial dimensions. Neither did the art of Buddhism know the frame as a delimiting boundary. In ancient China and Japan the slightest nuances in brush strokes were valued. Nevertheless, the artist and viewer put stamps onto the pictorial surface itself: they did not think of it as connected with the background.5 In the context of pantheistic mysticism of the Buddhist picture, it represents reality itself, a striving to show the fusion of the natural and the divine in the world. This determined its form in the shape of a horizontal and vertical scroll, embodying not a window into another space, but actually the surrounding cosmos itself in all its uninterruptedness and multiformity. On a horizontal scroll the pictures are not separated from one another, but rather presented in a definite sequence from right to left, while on a vertical scroll the landscape is structured so that the human gaze grasps the whole composition at once.6 Hence in Japanese medieval architecture the idea of the façade as boundary between the house and surrounding space is also absent. In a traditional Japanese house a person always looks from the interior outwards: he or she surveys maybe the landscape, maybe a small garden, since the outside walls of the house are able to slide apart.

During antiquity the representation separated itself off from surrounding space. In numerous Roman wall paintings imitating landscapes we find frames in the form of a ‘window on the world’, while in theatrical decor we find the beginnings of true perspective. However, the antique concept of the universal presence of the divine principle in the world also failed to accentuate the frame as a boundary between the worldly and the divine that was characteristic of pagan religions. Thales of Miletus (c. 624–546 BC), the first of the Seven Sages, pronounced that ‘everything is filled with the gods’. For that reason the frame in antiquity is a niche or the pedestal of a statue, or the architectural composition of a door, a window or a wall. Frames were also constituted by acanthus, palmate or meander ornaments and various geometric figures surrounding the antique mosaics and frescoes that were so startlingly beautiful and full of feeling. All these were a part of the work of art itself, however, and their function was to underline anew the harmony and sensibility of the whole, to demarcate the temple, sculpture or picture within surrounding space and simultaneously to ‘open up’ one to the other, to dissolve the boundary between the sacred and the profane in the cognitive model of divine omnipresence. In this sense the severe and massive walls of a Byzantine church are significantly different from the ‘transparent’ colonnades of Greek temples, thanks to which a god does not seem remote from the world. An antique temple is ‘open’ to the surrounding world and, as Heidegger remarked, ‘it contains within itself the aspect of the god and, while shutting it away in its closed cell, permits the aspect of the god to come forth into the sacred precinct of the temple through the open colonnade’.7 For the live figure of an emperor, an open portico and a pedestal lifting him above the surroundings serve as an analogous type of framing. Accommodating his statue or that of a pagan god there would be a three-dimensional niche in a wall, shutting the figure off only from one side and underlining its physical presence, or similarly a pedestal, lifting the statue upwards into the surrounding cosmos as if up a flight of stairs. All these possibilities represent an ‘open’, spatially constituted frame, whose chief function was to persuade humanity of its kinship with higher personages in the universe. To put it another way, antique art considered the frame not as a symbolic barrier, but as an instrument for concentrating attention on the image, as part of its composition and of the organization of artistic and surrounding real space.8

All the same in late antiquity we encounter certain framing constructions that in the future would be adapted to Christian images on boards. Scholarly observations on the Faiyyum portraits and on pictorial representations of pagan gods are of particular interest here. A Faiyyum portrait of the first century AD, discovered by the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1888, for example, has an eight-sided wooden frame reminiscent of frames on Christian icons of the sixth and seventh centuries recorded by Kurt Weitzmann in St Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai (illus. 3).9 An analogous frame is found on an antique prayer image in the Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels (illus. 4).10 Moreover, on two Sinai icons of the sixth or seventh century, regarded as among the earliest Christian icons, the representations of Christ and the Apostle Peter are shown against the background of an antique niche, which will eventually become the ark of an icon. All this tells us that it was from classical antiquity that early Christianity borrowed all kinds of forms and images, giving them a new symbolic meaning. The icon Christ in Glory (seventh century, illus. 5) from the Sinai monastery has retained an ancient frame that distantly recalls both the frame of a Faiyum portrait and those of late antique representations of gods. However, unlike the Faiyum portrait frames, that of the icon has been given clear symbolic significance. This frame forms an ark that is on the one hand uninterruptedly connected with the actual picture, and on the other with the surrounding space and with the person who no doubt placed it in the Sinai monastery: so we read on the frame the Greek inscription ‘For the salvation and exculpation of the sins of Thy slave, who loveth Christ . . .’.

Thus the tradition of antiquity encountered that of the Old Testament in the space of the material frame of the medieval Christian icon. It was in fact the Old Testament tradition, distancing God from the world, that first accentuated the symbolism of the frame as a distinct boundary between God and the world. The Old Testament Ark of the Covenant was a sealed box that would safely keep holy objects away from the eyes of unconsecrated people. We read in the Bible (Exodus 25:1–14):

And the Lord spake . . . they shall make an ark of shittim wood . . . And thou shalt overlay it with pure gold, within and without shalt thou overlay it, and shalt make upon it a crown of gold round about . . . And thou shalt make staves of shittim wood, and overlay them with gold. And thou shalt put the staves into the rings by the sides of the ark, that the ark may be borne with them.

6 Smolensk Mother of God, c. 1250–1300. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Traditionally, the ‘golden pot that had manna, and Aaron’s rod that budded, and the tables of the covenant’ (Hebrews 9:4) were kept in the ark. Thus the icon frame in the Orthodox tradition was connected with the Old Testament tradition of concealment of holy objects and was considered as inviolable as the image itself. Thus, for example, the sawing down of the margins of an icon might be considered blasphemy in Russia as late as the eighteenth century, as witnessed by the accusations of blasphemy, between 1764 and 1767, levelled against a certain Iust, who trimmed down an icon with the intention of putting it into an iconostasis.11

This function of concealing the holy object was performed also by the metal overlay of the icon, its casing and curtain cloths. All these served as an ‘ark’ and ‘adornment’ for the sacred countenance, separating it out and protecting it within the surrounding space. Early Byzantine texts tell us that the original icon of Christ – the Saviour Not Made by Hands on a sacred shroud – was kept above the city gate of Edessa, wrapped in a white cloth and placed in a chest (that is, an ark or a case). This case had shutters that were opened only on certain days, inspiring in believers the sense of the sacred object’s inviolability and protection from the ey...