![]()

1 The Lord’s Arms: Knighthood, War and Play

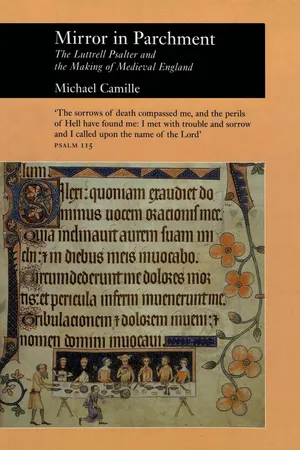

Few medieval manuscripts bear the stamp of personal ownership quite so insistently as the Luttrell Psalter, in which a splendid equestrian portrayal of its owner is introduced by the inscription ‘Dns Galfridus louterell me fieri fecit’ – ‘The Lord Geoffrey Luttrell caused me to be made’ (illus. 29). In contrast to the rich detail of the image of this man, what we know today about his life is sketchy, traceable only in official records like the royal Chancery rolls. In one such document, made at his father’s death in 1297, Geoffrey gave proof of his age, indicating that he was born at Irnham in May 1276, but no evidence remains of his childhood or education.1 Most surviving documents relate to his public life and are writs dated between 1297 and 1325 summoning him for the knightly military service he owed the king, but we do not know when he was officially dubbed knight.2 Yet here is a quintessential image of medieval knighthood, showing Geoffrey mounted on his great warhorse and depicted as the ideal representative of this warrior class in relation both to those whom he lorded over and to his own lord, God. Reproduced in hundreds of publications on English history and chivalry since 1794 (illus. 6), where it is usually isolated from its context, this is a picture that can be fully understood only when seen, as part of the double-page opening in which it appears (illus. 29–30) and integrated with the text of the psalms that surrounds it, as Geoffrey’s projected self-image – a portrait of the way he wanted the world to see him.

‘My Lord said to my Lord’

Traditionally, donors in manuscripts and other forms of medieval art are shown kneeling before the object of their devotion, usually Christ or the Virgin Mary. Not so Geoffrey Luttrell, whose gaze seems set not upon God, but upon himself. This ‘portrait’ is the only rectangular, framed picture in the whole psalter and appears not at the beginning of the book, as we might expect, but towards its end, at the bottom of fol. 202V. directly before Psalm 109, which begins at the top of the next page. The planner of the volume clearly intended that a miniature should fill this large space, which was left at the end of a quire which exceptionally consists of a gathering of ten, rather than the usual twelve, leaves. The scribe also wrote out the inscription before the portrait in the ornate Gothic script he had used throughout. It may have been Geoffrey himself who chose this crucial point at which to position himself in his book. It is at one of the five traditional major text divisions in fourteenth-century psalters, directly before Psalm 109, which was the first psalm sung at Sunday vespers and one of the most martial in its imagery: ‘Dixit Dominus Domino meo’, ‘The Lord said unto my Lord, sitteth thou at my right hand until I make thine enemies thy footstool’ (illus. 30).

The initial ‘D’ opposite, which opens the psalm, is itself unusual, for instead of the usual scene of two persons of the Trinity (the second ‘lord’ being Christ), here God the Father (the heavenly lord) talks to an enthroned King David (the earthly lord) who sits at his right hand. God holds the orb of the world, divided into its three continents, and David, who bears no halo, holds a sceptre. This comparatively rare iconography of David as the second lord strengthens the secular associations of Sir Geoffrey’s lordship opposite and is found in only a few other examples. The Commentary on the Psalms written by the Dominican Nicolas Trivet in 1318 provides a similar historical, as opposed to Christological, interpretation of the second lord, stating that ‘the Hebrew “don” can mean both God and man, as “Kyrios” in Greek and “dominus” in Latin’. Although Sir Geoffrey did not go as far as Charles V of France, who in his breviary of 1364–70 had himself represented within the initial of the same psalm as the lord invited to sit next to the deity, the juxtaposition of the knight and the historical conqueror King David is almost as audacious.3 Geoffrey’s own overlord and king when the psalter was commissioned was Edward III, who had succeeded his murdered and deposed father in 1327 but only took full control and the right to sit at the right hand of God some three years later.

The three ‘lords’ – knight, king and God – are differentiated as words in their palaeography (Sir Geoffrey is signified by the abbreviation Dns rather than Dominus) but as psalms were read aloud they would have sounded exactly the same. It was Geoffrey’s technical status as a baron – a particular form of landholding defined by the payment of relief – which gave him the right to call himself lord of Irnham. The title Dominus was an important distinction in fourteenth-century England and was used to address not only beneficed knights but also chaplains and monks. It had other connotations that mingled sacred and secular. According to a late thirteenth-century sermon on God’s love, ‘The Lord (dominus) has a just feudal service (servitium) and a just customary payment (censum) in all our lands because he is the Lord. Therefore, we who are his feudal tenants (feodotarii) owe him from the manor of our heart, the servitium of love.’4 But at this point in the psalter it is not the word, but the image which takes control.

The integration of picture and psalm is so close here that the two ends of the crest fixed to Geoffrey’s helm and the silver tip of his pennon break the frame to point to the letters ‘o’ and ‘u’ of his name. The second verse of the psalm that follows suggests that this weapon was also seen as a sacred sign of authority, the ‘virgam virtutis’ the ‘sceptre of thy power’ with which the lord God will destroy the ranks of his enemies ‘dominare in medio inimicorum tuorum’. Preparing ‘to make thine enemies thy footstool’ is literally what is depicted here for it was part of the knight’s duty of unpaid feudal service which he owed to his overlord, the king. Knighthood entitled one to bear a coat of arms but it was not hereditary in England as it was in France. It was conferred as an honour on the recipient by a king or magnate but was open to all those who held a certain degree of landed wealth, normally set at £40 a year. By 1324 there were about 860 knights in England, sixty-two of them in Lincolnshire alone.5 However, this was a period which saw a widening gap between nobles and other members of the social order and an actual decline in the number of knights in the county.6 Knights had first distinguished themselves by going on horseback centuries before, and the distinction between those who ride and those who go on foot is a major one in the articulation of status in the Luttrell Psalter.

What distinguishes this knight from all these others – and what took up most of the illuminator’s time, materials and skill – is the delineation, not of his physical appearance, but of his family arms. Although there were over 3,000 noble families in late medieval England, and coats of arms were assumed not only by them but increasingly by merchants and craftsmen, and even peasants, they were still an exclusive status symbol. As described in blazon (the conventional language of heraldry) these are Azure a bend between six martlets argent and can be seen on Geoffrey’s surcoat, his enormous square shoulder ailettes, his pennon and the fan-like crest of his helm.7 His warhorse or destrier, often the most expensive of all the items needed by a knight, also bears them on its saddle, fancrest and long flowing trapper.8 Silver (argent) not only shapes the charger’s shoes and the sharp warhead of Geoffrey’s lance, but is used to great effect in the metal tinctures of the martlets, the birds, which change from silver to gold. These have oxidized somewhat over the centuries but would have shimmered radiantly on the surface of the page. Significantly, this image is the work of the leading illuminator of at least six who were involved in the decoration of the book. Elsewhere this artist shows off his ability to evoke the textures and details of animals and plants but here the aim is the opposite – he alludes to the richness of what has been manufactured, particularly embroidered textiles, which were a far more expensive and prestigious form of art than most manuscripts. White highlights, a feature of this illuminator’s repertoire, are used not only to give definition to the mouth and wrinkles on Geoffrey’s profile, which protrudes under the protective skullcap or bacinet worn over his mail coif, but also to decorate the beautiful blue trapper with a swirling floral pattern. This splits open symmetrically at the front, another often-used pictorial device of this artist who, as we shall see, liked to open up and reveal linings and the insides or undersides of clothing worn by the whole range of social types. Here it shows off the rich red lining and also bares the horse’s dappled white flank (thus showing its pedigree) as well as the sharp metallic florettes of Geoffrey’s spurs. Another eyecatching effect is the raised and embossed background which seems to hang behind the figures like a sumptuous gold brocade.

Is this image, which is so ‘loaded’ symbolically and materially, the representation of an actual event? Arming knights for battle, popular in other visual and literary sources of the period, was a major ritual for defining chivalric identity. Handing Geoffrey his enormous helm, the most crucial of all the pieces of his protective armour in the clash of battle, is his wife Agnes, who was a daughter of Sir Richard Sutton, an important Nottinghamshire magnate and a nephew of Oliver Sutton, bishop of Lincoln (1280–99). We do not know the date of Agnes’s birth, nor when she married Geoffrey, but she was probably younger than her husband and died in 1340 after bearing him at least six children: four sons and two daughters. Her own important family ties are articulated on her gown, which bears the arms of Luttrell impaled with those of Sutton (Or a lion rampant vert). Her golden lions also run along the lower border of the facing page (illus. 30) and join in the corner with her husband’s martlets, framing the whole folio with their emblazoned union. This image of Agnes handing Geoffrey his warrior’s helm has often been compared with those of the knight being armed by his beloved, such as the female figure at the centre of the contemporary parcel-gilt silver plate, called ‘The Bermondsey Dish’, in the Victoria & Albert Museum (illus. 13).9 But the Luttrell image emphasizes lineage over love, relationships of power rather than games of desire. Whereas in the silver dish the lady stands in the superior inspirational position at its centre as the knight’s ideal and he kneels subject to her, Agnes looks up to her lord and master, to whom she is subject. The silver and blue Luttrell martlets on her gown mark her as the property of her husband; her role in the spectacle is not to stand out as an individual, but to blend into the sparkling surface through which Geoffrey projects, and in which he reflects, himself.

13 ‘The Bermondsey Dish’, parcel-gilt silver, c. 1340–50, from the parish church of St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey, London. | |

The third figure in the scene, who stands waiting to hand over the Luttrell shield, seems visually to be more important, and she is. This is Geoffrey’s daughter-in-law Beatrice Scrope, whose family arms (Azure a bend or and a label of five points argent) are impaled with those of Luttrell on her gown. Her father was the powerful and politically ambitious lawyer and diplomat Geoffrey le Scrope, the king’s seargent at law and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench.10 In 1320 Beatrice, who was still in our terms a child, had been married to the Luttrell’s eldest son Andrew when the boy was seven years old, in a joint marriage ceremony with her sister, Constance, who married Andrew’s even younger brother. It had been through a similar advantageous union – marriage to the heiress Frethesant Paynell – that Geoffrey’s great-grandfather, also called Geoffrey, had gained the Irnham estate in about the year 1200.11

But by the time the Luttrell Psalter was produced, probably ten years after the wedding, the younger of the Luttrell sons and his Scrope bride were both dead and hopes for a future Luttrell heir were focused sharply on the body of Beatrice. This is why she appears so prominently here, holding in her hands the most potent and public family symbol in the whole picture – the shield, which was identical to that on Geoffrey Luttrell’s seal.12 Originally, as Brigitte Rezak has explained, knights’ seals had carried the image of the mounted warrior because ‘it was the military function which had allowed their assimilation into the noble group’, but by the fourteenth century this had been replaced by the simple shield, which symbolized ‘. . . the identity of a family which, having freed itself from the status of domestic retainer, had developed personal power and judicial privileges, genealogical consciousnes and hereditary transmission: a family constituted as a dynastic lineage’.13 In recuperating the equestrian type for the portrait, Geoffrey’s image looks backwards self-consciously to an earlier, chivalric golden age, before signs became associated with surfaces, and to the previous great men in his blood-line. Dynastic concerns are also evoked in the preceding text, of Psalm 108 VV. 9–13, with its warnings that for the ungodly man, his wife will be a widow, his children orphans and, worst of all, ‘may his posterity be cut off; in one generation may his name be blotted out’. This image might indeed be seen as one which, as well as celebrating the family name, articulates exactly that anxiety about its continuity. As one leading historian of the English nobility has put it: ‘It is not generally realized how near to extinction most families were; their survival was always in the balance and only a tiny handful managed to hang on in the male line from one century to another.’14 It is precisely this future fertility of the Luttrell family, precarious at best and finally to f...