![]()

Introduction: Walter Benjamin and the Birth of Photography

Walter Benjamin was born into a world in which photography was becoming commonplace. In 1892, in Berlin, the year and place of his birth, photography wove its way into many people’s lives through the ritual visit of the bourgeois family to the studio to have portraits taken, an experience that Benjamin reflected on several times in his writings. In autobiographical reflections from the early 1930s, he relates how when as a child he was photographed in a studio with a crudely painted backdrop of the Alps, brandishing a kidskin hat, he felt that the screens and pedestals ‘craved my image much as the shades of Hades craved the blood of the sacrificial animal’. The photographic studio presented itself to him as a hybrid of boudoir and torture chamber.1 And there exists a photograph of him, at the age of five, standing alone, surrounded by a fuzzy oval, holding a sword and a flag and dressed up as a soldier. Studio photography compelled the subject, he noted, to adopt awkward poses, dress in clothes that are nothing but costumes, and gaze out from among a clutter of fake and random objects that engulf the fragile human body. Indeed, the imposturous and miserable but also simultaneously widespread nature of this experience is covertly publicized when Benjamin describes an image of Kafka that was in his possession. It is of Kafka as a boy, yet Benjamin describes it as if it were of himself:

I am standing there bareheaded, my left hand holding a giant sombrero which I dangle with studied grace. My right hand is occupied with a walking stick, whose curved handle can be seen in the foreground, while its tip remains hidden in a bunch of flowers spilling from a garden table.2

In Benjamin’s interpretation, mechanical reproduction, or photography in this case and at this moment, assaults humanity and provides legible images of the dysfunctional relationship of technology, nature and social world by which humans increasingly become mere props – an experience not reserved solely for the working-class ‘appendage of the machine’, as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described it in 1848 in The Communist Manifesto. This is how Benjamin saw a world of commercial photography designed to provide confidence-boosting photographs for well-heeled families to place inside heavy albums that rest as dust traps on dark sideboards in cluttered living rooms.

There were also more public encounters with photography in Benjamin’s childhood. The time of his growing up was the time of the emergence of the illustrated press, which was dependent on the rapid technical innovations in the field. In his year of birth, for example, the Berlin Illustrirte Zeitung3 (Berlin Illustrated Newspaper) first appeared, placing its speciality attention-grabbing pictures on its front cover. Engravings were soon replaced by photographs and, from 1901, photographs were printed inside the newspaper. Here was the start of photojournalism, and with it the professions of photojournalist and photo librarian were established.

As Benjamin grew, so too did access to making photographs. Processes simplified – cheaper cameras were made and roll film was invented. In February 1900, Eastman Kodak Co. introduced to the U.S. market the Brownie camera, designed and manufactured for the company by Frank Brownell of Rochester, New York; the name ‘Brownie’ was a reference to the pixie-like characters from Palmer Cox’s popular children’s books, and illustrations of them appeared on the cameras’ early packaging. The young camera was, after all, designed for children. The new photography was to be a hobby for children, for the apparatus could be ‘operated by any school boy or girl’, as an advertisement from the Youth’s Companion put it in May 1900. In the event, much larger sections of the population adopted it. With the Brownie, the notion of the snapshot was inaugurated. Rapidly other companies started making similar cameras and they came into the hands of Europeans too. Moments of daily life, or at least its exhilarated moments – at the beach, on the town, in the garden – were recorded for posterity.

The invention in Germany of the Leica camera prototype, by a microscope designer on the eve of the First World War, contributed further to the pervasion of the world by photography. Once the war was over and the prototype improved, the Leica revealed itself to be a versatile, eye-level, daylight loadable compact camera that could snap precise shots in magnificent detail, using 35 mm motion picture film, which enabled it to shoot up to 36 rapid sequential exposures. Fast-paced modern life could be framed and captured by this device. During Benjamin’s passage from baby to adult, photography had developed: it had become faster, more capable and yet, in some regards, less demanding of skill on the part of the photographer.

Private and public, collective and individual, active and passive, productive and consumerist engagements with photography were all possible in the world in which Benjamin grew up. Photography had entwined itself in the mediation of the world. It had become not just a mediator of history but by the 1920s also had its own rich history and assured future. Benjamin reflected on all this in his scattered writings and jottings on photography. His thoughts encompass production, reproduction, sitter, viewer, temporality in the photograph, the economic situation of the photographer and this vis-à-vis the painter, the status of art and craft in relation to photography, the relationship of his curious category of ‘aura’ to photography, the relation of photography and memory, and photography’s potentials for knowledge and pedagogy.

Benjamin was aware of some of the debates around and practices of photography, not just as a bystander but as a discussant. In the course of his life, he came to know several professional photographers, including Sasha Stone, Gisèle Freund and Germaine Krull, and he made the acquaintance of John Heartfield.4 He met László Moholy-Nagy through Arthur Müller-Lehning, the Dutch anarchist who was the publisher of the Dutch International Revue i 10, a journal for which Moholy-Nagy was photography and film editor from 1927 to 1929. A letter from Benjamin to Gershom Scholem from 14 February 1929 mentions meeting Moholy-Nagy: ‘A thoroughly delightful physiognomy – but perhaps I have written this before – is Moholy-Nagy, the former teacher of photography at the Bauhaus.’5 Some of Benjamin’s ideas on photography coincide with aspects of Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei Photographie Film (Painting Photography Film), published in 1925 as a contribution to the Bauhaus book series, with a second edition in 1927 (where the occurrences of ‘ph’ in Photographie were replaced by the more modern-sounding ‘f’ form. In this book, Moholy-Nagy argues that a ‘culture of light’, drawn from ‘the new vision’ that is produced by the camera as it extends the eye, will adopt the mantle of innovation from painting and provide the expressive means of the future.6

Photography in Weimar Germany

Walter Benjamin was not alone in turning to photography as a fount of interest. The Weimar Republic of Germany, in which he lived and studied until 1933 and where (having failed to secure an academic post) he became a reviewer and essay writer, housed a lively photographic culture. In 1929 the much-publicized ‘Film und Foto’ exhibition opened in Stuttgart, organized for the Deutscher Werkbund by Gustav Stotz in order to ‘bring together as comprehensively as possible works of all those who were the first to recognize that the camera is the most appropriate composition medium of our time and have worked with it’.7 Around 1,200 works were on view, selected from across Europe and the United States, and the show, in reduced form, toured for two years through Zurich, Berlin, Vienna, Danzig, Zagreb and Munich, and also went to Japan. ‘Film und Foto’ was a bold statement, phrased in Germany, about the importance of technological culture. The exhibition sampled some of the tendencies of photography in Europe of recent years. These tendencies, some of which were represented in the exhibition and all of which were practised in Germany, ranged from commercial photography to reportage photo-essays, art photography, avant-garde photobooks and political photomontage. Even within art photography, photographic trends ranged, within just a few years, from the quirky framings and high contrast of the Neues Sehen (New Vision), to the documentary precision and hyperrealism of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity, or ‘Straight Photography’ as it was called in the U.S.), to Dada and Surrealist approaches to the image.

Sasha Stone, The East, 1920s, published in Schünemanns Monatshefte (August 1929).

Photography was embraced by a panoply of users. Its origins in a mechanical device were overcome in its diversion into a bona fide art form; provided the basis for its rhetoric of objectivity, precision and truthfulness, which allowed it to be used as an investigative tool capable of capturing, assessing and retransmitting the contours of modern life; and allowed it to forward anti-art and post-art arguments among an avant-garde that rejected the association of art with individual creativity, originality and authorship. Numerous volumes of experimental photography were published in the 1920s, such as Erich Mendelsohn’s Amerika: Bilderbuch eines Architekten (America: Picture Book of an Architect, 1926), with its captioned day and night shots, reviewed favourably by El Lissitzky, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Bertolt Brecht; Werner Graeff’s Es kommt der neuer Fotograf! (The New Photograph is Coming, 1929); and Jan Tschichold and Franz Roh’s foto-auge / oeil et photo / photo eye, published in 1929.8 These collections were polemical. In foto-auge, a response to ‘Film und Foto’, Roh, eschewing the upper case, established the following context for the volume that conveyed a ‘new vision’:

for a long time we had photographers who clad everything in twilight (imitators of Rembrandt in velvet cap, or all softening impressionist minds). today everything is brought out clearly.9

It contained 76 photographs by Eugène Atget, Andreas Feininger, George Grosz, Max Burchartz, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Herbert Bayer, László Moholy-Nagy, Edward Weston and others. The cover illustration was a photomontage by El Lissitzky. But as well as photographs by named practitioners experimenting with montage, photograms, multiple exposures, negative prints and collage, in addition to photography combined with graphic, painterly or typographical elements, it contained anonymous photographs from newspapers, picture agencies and advertising, aerial photography, X-ray images and the results of other scientific uses of the camera. These were all jumbled together and without captions. Juxtaposition was one of foto auge’s modes of communication; for example, ‘Files’, a photograph by Sasha Stone of alphabetized index cards in a filing cabinet, was placed next to an image owned by the chemical concern IG Farben, of people relaxing on a beach. The meanings of each – work, leisure, mass society, loss of individuality, public, private, surveillance, bureaucracy – were modulated by the other.

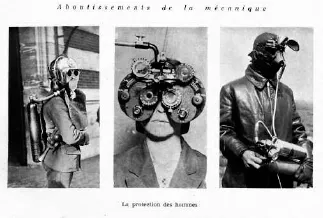

Achievements of Mechanics, published in Variétés (15 January 1930).

Periodically living in Paris, Benjamin also had at least an inkling of what was of interest among the francophone scene. He was aware of journals that dealt with modern photography and film, mentioning in particular the French journal Bifur and the Belgian Variétés, both of which had relationships with Surrealist photographers. To give a sense of the material on show in such a forum as Bifur, some of the contents of issue 5 from 1930 will suffice: photos by Claude Cahun and Tina Modotti and film stills from Sergei Eisenstein and Joris Ivens. Variétés made heavy use of photography too in its issues, under the influence of the Dada-Surrealist E.L.T. Mesens, who produced collages for the journal and published images by contemporary photographers, including Germaine Krull.10

In Europe in the 1920s, how photographs looked and how they could be made was a topic for excited debate. Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray experimented with direct photography and darkroom trickery. In the post-revolutionary Soviet Union, Aleksandr Rodchenko insisted on breaking with straight-ahead views and used the new lightweight cameras to take tilted shots, their perspectival shifts designed to signify the shift in political perspectives. John Heartfield and Hannah Höch snipped images from illustrated magazines, transforming the seemingly ordinary signs that they found into warning signals of oppressions to come. Neue Sachlichkeit rebuffed photomontage’s fractures with smooth, glossy images whose framing and tones oozed a cool attitude rather than the heat of the struggle. Some contemporaries – Benjamin among them – dismissed it as the photography of political impotence attuned to a period of stabilization. In 1924, Benjamin evoked the polar opposite of ‘objective’ photography in translating into German – with ‘awe-inspiring vim’11 – a short piece entitled ‘Insideout Photography’, for the June 1924 issue of G: Zeitschrift für elementare Gestaltung (G: Magazine for Elementary Form), journal of the ‘G’ group. The article was Tristan Tzara’s 1922 preface to Man Ray’s photograph album Les Champs délicieux, devoted to his Rayographs, which were photographs taken without the use of a camera. Tzara wrote:

When everything that called itself art was well and truly riddled with rheumatism, the photographer lit the lamp of a thousand candles and step by step the light-sensitive paper absorbed the blackness of several objects of use. He had discovered the momentousness of a tender and unspoilt flash of lightning, which was more important than all the constellations designed to bedazzle our eyes. Precise, unique and correct mechanical deformation is fixed, smooth and filtered like a head of hair through a comb of li...