![]()

1

Tribal Pakistan: The Epicentre of Global Terrorism

The Pakistani public as a whole is now more favorable toward the Taliban than it was before the attacks of September 11 and recognizes no compelling reasons to cut Pakistan’s traditionally strong links with the Taliban government.1

Pakistan has not been responsive to [American] requests that it use its full influence on the Taliban surrender of Bin Ladin.2

There are terrorists holed up in those mountains who murdered 3,000 Americans. They are plotting to strike again. If we have actionable intelligence about high-value terrorist targets and President Musharraf will not act, we will.3

Threat Landscape

Terrorism, guerrilla warfare and insurgency have emerged as the pre-eminent national security threats to most countries in the early twenty-first century. The threat is spreading from conflict zones to neighbouring regions and countries far away. Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan are among the best-known case studies. The spectrum of threat groups includes both Muslim and non-Muslim groups, but Al Qaeda presents the most formi dable threat.

Afghanistan, a conflict zone stemming from international neglect after the Soviet withdrawal, emerged as the epicentre of terrorism until the US-led intervention. Since then, the ground zero of international terrorism has shifted from Afghanistan to Pakistan’s tribal region. Many of the major terrorist attacks attempted or conducted in the West after 9/11 have been organized or inspired by Al Qaeda’s senior leadership located in this rugged and inaccessible mountainous region. Three profound developments characterize the post-9/11 global threat.

First, after the US-led intervention in Afghanistan, the ground zero of terrorism moved from Afghanistan to FATA, which is now the single most important base of operations, a place where leaders, trainers and planners are all located.

Second, after the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, Al Qaeda relocated to FATA, thereby gaining a foothold in the Middle East and esta blishing a forward operational base closer to the West. From FATA, Al Qaeda could direct operations globally, including the ongoing battle in Iraq.

Third, by investing in sustained communication and propaganda from FATA, Al Qaeda co-opted several like-minded groups in Asia and the Middle East. In place of one single Al Qaeda, there are several Al-Qaedas: Tawhid Wal Jihad became Al Qaeda in Iraq, the Salafist Group for Call and Combat became Al Qaeda Organization of the Islamic Maghreb, and Al-Jemmah Al-Islamiyah’s Noordin Mohammad Top Faction became Al Qaeda Organization of the Malay Archipelago.4

The long-term strategic significance of Al Qaeda successfully carving out a semi-safe haven in FATA is yet to be realized. In addition to the inaccessible Afghan–Pakistan border emerging as the new headquarters of the global jihad movement, Al Qaeda and its associates are seeking to change the geopolitics of the region. Together with self-radicalized, home-grown cells, they have recruited globally and struck at Al Qaeda’s enemies both through its operational network and through cells it has inspired. Groups trained in FATA are mounting attacks in western China (Xinjiang), Iraq, Algeria, Somalia and other conflict zones. As the assassination attempts on leaders in both Pakistan and Afghanistan show, Al Qaeda and its associated groups aim to eliminate leaders who are hostile to the terrorists and extremists. The subject of Al Qaeda dominates the inter national media, but until the London bombings in July 2005 its active presence in FATA was not a subject of intense international debate.

Tribal Pakistan

The variables that should be explored to understand this myriad of problems include colonial administrative/political and judicial structures of governance, Pashtun cultural code (Pashtunwali), the nature of the Pakistan–Afghan border, the socio-economic profile, the Pakistan military’s approach to counter militancy and the resultant rise of militant Islam.

Background

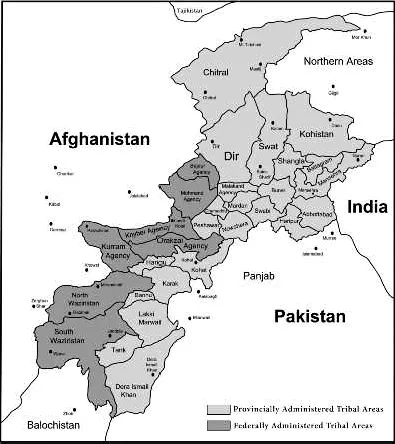

The tribal areas of Pakistan known as Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in the constitution of Pakistan5 comprise seven tribal agencies (Bajur, Orakzai, Mohmand, Khyber, Kurram, North Waziristan, South Waziristan) and six frontier regions: Frontier Region (FR) Peshawar, Frontier Region (FR) Kohat, Frontier Region (FR) Bannu, Frontier Region (FR) Laki Marwat, Frontier Region (FR) Dera Ismail Khan and Frontier Region (FR) Tank. The name FATA is a misnomer.6 Islamabad has never maintained jurisdiction over more than 100m either side of the few government-built roads in the tribal areas. FATA functions as a semi-autonomous region. In theory, tribal areas come under the federal government’s jurisdiction, but in practice they are autonomous.

The Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan.

FATA covers an area of 27,220 square kilometres and is located on the porous north-western border known as the Durand Line, 1,200km long, between Pakistan and Afghanistan. To the north is the Lower Dir district in the KP, and to the east are the KP districts of Bannu, Charsadda, Dera Ismail Khan, Karak, Kohat, Lakki Marwat, Malakand, Nowshera and Peshawar. The district of Dera Ghazi Khan in the Punjab province lies to the south-east, while the Musa Khel and Zhob districts of Baluchistan are situated to the south. Afghanistan lies to the west of FATA.7

The population of FATA stood at 3.2 million according to the 1998 national census (the current estimate is 3.5 million) and most belong to Pashtun tribes. The latest weaponry abounds because of the Afghan jihad and it is customary to carry arms. Basic amenities are scarce and religious conservatism holds sway. Afghan jihad, and the state’s deliberate attempt to promote pro-jihadist elements, has resulted in the local clergy’s monopoly over these areas.

Historically the British colonial administrators of India used FATA as a buffer against Russian expansionism in Central Asia. The colonial government did not exercise absolute control over FATA:

Colonial administrators oversaw but never fully controlled the region through a combination of British-appointed agents and local tribal elders. The people were free to govern internal affairs according to tribal codes, while the colonial administration held authority in what were known as ‘protected’ and ‘administered’ areas over all matters related to the security of British India.

Although various tribes cooperated with the British on and off in return for financial incentives . . . this quid pro quo arrangement was never completely successful. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, British troops were embroiled in repeated battles with various tribes in the area. Between 1871 and 1876, the colonial administration imposed a series of laws, the Frontier Crimes Regulations [FCR], prescribing special procedures for the tribal areas, distinct from the criminal and civil laws that were in force elsewhere in British India. These regulations, which were based on the idea of collective territorial responsibility and provided for dispute resolution to take place through a jirga (council of elders), also proved to be inadequate.8

After the promulgation of the FCR, FATA remained a constant source of trouble for the British government. The political autonomy to which FATA was entitled through the FCR always benefited non-state actors in one way or another. Since the British era inaccessible areas have existed where the state has had no presence, providing space for criminals and militants.9 Tribes regulated their own affairs according to their customs and unwritten codes. They never recognized the British-drawn Durand Line, a poorly marked border separating Pakistan and Afghanistan. The people of FATA and southern Afghanistan had, over the centuries, interacted very closely during all the major events in the region. This has been greatly facilitated by the porous border. It is not surprising that smuggling, particularly in narcotics from Afghanistan, has become lucrative.

When Pakistan gained independence from British rule in 1947, the existing administration of the tribal areas was preserved. The seven agencies of FATA came under the control of the President through the governor of KP. There was relative peace in the tribal region after the creation of Pakistan, with no major unrest or armed movement. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, however, the Afghan Jihad radically changed the social fabric of Pakistani society. The tribal belt of Pakistan became radicalized. Due to its geographic proximity to Afghanistan, FATA was affected the most. The tradition of carrying weapons that is part of tribal culture made possible the systematic militarization of FATA, which was used as the launching pad for the holy warriors coming from all over the world to fight against the ‘godless’ Soviets. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), through the Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI), funnelled in huge sums of money to help create madrasas to train a generation in warfare and militancy.10 The Jihadi forces, supported by Pakistan, the US, Saudi Arabia and other major western countries, emerged victorious and the Soviet forces were driven out of Afghanistan in 1989. After the Soviet withdrawal, however, Pakistan was abandoned to face the consequences of an unfinished war. According to some estimates, more than 70,000 warriors from Pakistan and other countries were recruited and trained for Afghan Jihad. For Pakistan, with its limited resources and capabilities, it was an impossible task to rehabilitate thousands of battle-hardened fighters and bring them back into the mainstream. A dominant majority of Afghan-trained fighters turned their guns against Pakistan and a few opted to move to the conflict zones of Kashmir, Chechnya, Arakan (Myanmar), Mindanao (Philippines), southern Thailand, Eritrea and Palestine.

Political Economy of FATA

FATA is Pakistan’s most impoverished and economically backward area. In the name of preserving traditional tribal culture and the independence of Pashtun tribes, these areas have been deliberately kept backwards over the years. Since independence, because no major development has taken place, we have seen political alienation, economic deprivation and deep-seated resentment against the centre. The political administration in FATA is the main vehicle for economic development and planning. As a result of state manipulation, developmental funds are neither invested in infrastructural development, nor do they reach the masses; instead they reach only the local elite, the state’s hand-picked functionaries.11 This manipulative and selective patronage of the local elite by the state authorities has resulted in a resource gap between those who have access to the administration and those who do not. The political agent’s economic tools and instruments of economic control include the allocation of permits for exports and imports in each agency.12

The colonial era legacy of using this region as a buffer has resulted in the chronic apathy of the central government and kept the region grossly underdeveloped. The socio-economic and demographic indicators are abysmally poor. By raising the bogus threat of Pashtun separatism, the central government has denied the people in the tribal areas their economic and political rights. The lack of a participatory system of governance at the grassroots, the bias in favour of a traditional feudal economic system, and a social hierarchy that creates conditions favourable for the perpetuation of a cycle of underdevelopment have promoted the growth of militancy and religious conservatism.13

FATA’s per capita income is half that of Pakistan’s national average (US$500). More than 60 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line and per capita development expenditure is one-third of the national average. Only 2.7 per cent of the population in the Tribal Areas lives in its towns, and the ratio of roads per square kilometre in FATA (0.017 per cent) compares to 0.26 per cent nationally. Overall literacy is 17.24 per cent, compared to 56 per cent nationally. While the male literacy rate is 29.5 per cent, female literacy is 3 per cent (32.6 per cent nationally). There are very few schools for females, and many have been closed, bombed or burned down because powerful religious leaders discourage female education. For the 3.1 million residents of FATA, there are only 41 hospitals, the people per doctor rate is 1:1,762 as compared to 1:1,359 nationally,14 and the population per bed in health institutions is 1:2,179, as against a national figure of 1:1,341. According to a World Health Organization report of 2001, nearly 75 per cent of the population has no access to clean drinking water. While problems of infant mortality are severe, the population growth rate is 3.9 pe...