![]()

1

Theories and Methods

As has been noticed by those few authors who have dealt at some length with iconoclasm, the destruction of art is a subject that most art historians prefer to ignore: Louis Réau saw it as a kind of taboo; Peter Moritz Pickshaus as a ‘non-theme’. David Freedberg, who considered that ‘in this case lack of interest is the same as repression’, explained that this was because iconoclasm ‘sears away any lingering notion that we may still have of the possibility of an idealistic or internally formalist basis for the history of art’, that is, the belief in an absolute autonomy of art (which, as we shall see, benefited much from iconoclasm).1

Images of iconoclasm

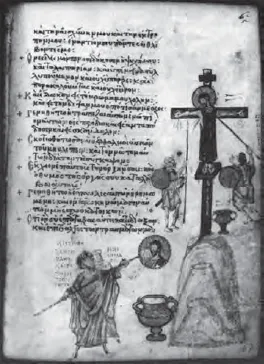

The sparse historiography on the subject that does exist belongs to the richer history of the condemnation of iconoclasm, a subject that has been explored even less, but can be traced in images as well as in texts.2 In Byzantium, iconoclasts were typically denounced as blasphemers, whose violence against religious imagery struck at the sacred prototype (illus. 3). But by the Reformation they tended to be exposed as ignorant as well as brutal, and art, just as much as religion, was seen to be their victim. The threat they represented thus played a negative but necessary part in kunstkamer paintings, programmatic representations of rooms displaying art, antiquities and natural curiosities painted by Flemish artists following the late sixteenth-century revolt of the Netherlands and the concurrent iconoclastic violence: several of these works include gesticulating figures with donkeys’ ears or faces – derived from allegories of Ignorance – menacing or destroying pictures with their clubs.3

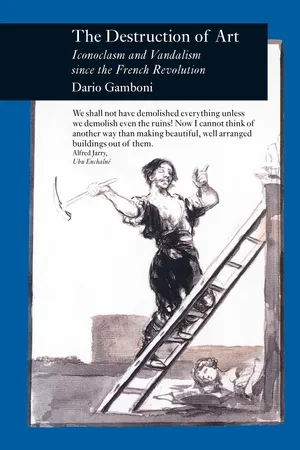

1 Francisco de Goya, No sabe que hace, c. 1814–17, brush drawing. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin. The drawing may allude to the anti-parliamentary violence that took place in Madrid in 1814 on Fernando VII’s return from France.

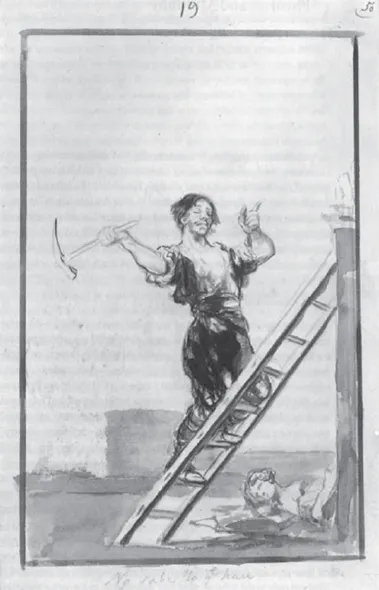

2 H. Baron, The Breaker of Images, etched by L. Massard, published in A. Challamel and Wilhelm Ténint, Les Français sous la Révolution (Paris, 1843). | |

Ignorance is a key concept in the stigmatization of iconoclasm. Encouragement of the arts, a feature of enlightened government, is presumed to dissipate the ignorance that fosters the destruction of art. Iconoclasts are presented as blind not only to the value of what they destroy, but to the very meaning of the acts they perform. Goya has supplied a striking expression of this idea (illus. 1). A man with his eyes shut tight is balanced precariously on a ladder, still waving the pickaxe he has just used to smash a bust; the caption reads: ‘He doesn’t know what he’s doing.’ Goya probably had in mind attacks directed against liberal institutions (represented by the smashed allegorical sculpture) rather than against art,4 but the opposition between destructive ignorance and creative enlightenment is the same. In his History of the Revolt of the Netherlands, written shortly before the French Revolution, Schiller attributed iconoclasm to the lowest sort of people caught up in riotous situations.5 Similar arguments were used by the Revolutionary defenders of the artistic heritage of the Ancien Régime, and the term ‘vandalism’ was coined to serve that end. A little-known engraving from the series of 1843 entitled Les Français sous la Révolution illustrates this common view of the destroyers of art (illus. 2). The gross appearance and ‘primitive’ features of the sans-culotte stress not only his low extraction but his underdeveloped nature (and, in the physiognomic and phrenological tradition, perhaps his criminal nature too); the elegant, demure and politically rather inoffensive character of the sculpture he is about to deface defines him as an enemy of beauty and culture much more than of tyranny.

Art destruction and art history

Since the history of art history is so closely associated with that of the growing autonomy of art, the historiography of iconoclasm cannot but possess a normative, even programmatic dimension. One major work belongs to the tradition of condemnation – Louis Réau’s Histoire du vandalism (1959). Réau really had two aims: one was to complete the history of French art, and especially of French architecture, with an inventory of works that had been lost; the other was to denounce the destruction, regardless of its causes, and prevent its continuation, or rather, to delegitimize in advance any future actions of that sort. His political ideal was obviously a stable hierarchic society in which the ‘base instincts of the crowd’ could be kept under control and where a high culture enjoyed the discriminating support and protection of the knowing and powerful. Not surprisingly, the ‘Vandalism’ of the French Revolution is given pride (or better, shame) of place in his ‘interminable obituary’, although none of the governments that followed is exempted from his reproaches.6 Réau’s polemical and pedagogical stance makes his ‘history’ an heir to the pamphlets by authors like Abbé Grégoire and Montalembert, who aimed at ‘inflicting publicity’ on the persons or institutions deemed responsible for destruction, ‘in order to mark out the guilty . . . and to caution ceaselessly the good citizens against errors of this kind’.7

At the opposite end, both theoretically and politically, is an equally important but incomparably more useful book, the collection of essays Martin Warnke edited in 1973 that bears the generalizing title Bildersturm (iconoclasm). This anthology was the result of the critical questioning of the idea of the autonomy of art in the context of the Ulmer Verein für Kunstwissenschaft, a radical university institution founded in West Germany in 1968. In his introduction Warnke stated that the authors’ common point of departure was the search for the historical roots of the idea, according to which any critical approach towards art amounted to a kind of ‘iconoclasm’.8 In a study of the ‘wars of images from late Antiquity to the Hussite revolution’ that was published two years later, Horst Bredekamp treated art as a ‘medium of social conflicts’ and saw their methodological value in the way they revealed how far what we consider retrospectively as pure ‘art’ had historically possessed other functions and significances.9 The war of reviews that followed these two books demonstrated that central issues were at stake.10

3 Comparison of the effacement of an image of Christ with the Crucifixion, from the Chludov Psalter, mid-9th century. State Historical Museum, Moscow. | |

In a first attempt at a general history of the destruction of art, published in 1915, the Hungarian historian Julius von Végh ascribed the relevance of his book to art as culture, or a part of culture, rather than to art as such.11 This was not only a way of justifying his enterprise and paying tribute to Jacob Burckhardt, for the conclusion of Vegh’s Bilderstürmer (iconoclasts), after pointing out the shortcomings of Tolstoi’s criticism of modern art, nevertheless defended the necessity for art to remain a part of broader ‘culture’.12 Most modern studies of iconoclastic episodes – which it is not my aim to enumerate here – are at least partly social histories of art and consider the violent treatment of the artefacts they examine as a special kind of reception and an indicator of functions, meanings and effects. Michael Baxandall thus resorted to an analysis of the destruction of statues in his book on the limewood sculptors of Renaissance Germany because of ‘what they imply about the status of the image before reformation’.13 David Freedberg integrated his interpretation of iconoclasm into the broader project of a ‘history of response’ that reclaimed for the history of images a ‘rightful place at the crossroads of history, anthropology and psychology’.14 Iconoclasm obviously stays on the agenda of a history of art that understands itself as part of the human and social sciences, and which is open to interdisciplinary exchanges. In recent years sociology and religious anthropology have greatly contributed to our understanding of the violent ‘uses of images’, as Olivier Christin acknowledged in his major study of Protestant iconoclasm in France.15 Unfortunately, destructive acts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have tended to be examined only superficially as elements of comparison, with the danger of postulating transhistorical continuities.

‘Iconoclasm’ and ‘vandalism’

So far, I have used the term ‘iconoclasm’ as equivalent to the ‘wilful destruction of art’, but the terminology must be examined here. English, like most European languages, has two terms to describe the kinds of destruction with which we are concerned: ‘iconoclasm’ and ‘vandalism’. Their perpetrators can be correspondingly identified as ‘iconoclasts’ or ‘vandals’. German proposes three possibilities in each case: Ikonoklasmus, Bildersturm and Vandalismus, and in turn the Ikonoklast, Bilderstürmer and Vandal. ‘Iconoclasm’ and its associates and equivalents come from the Greek terms for ‘breaking’ and ‘images’. They were used first in Greek in connection with the Byzantine ‘Quarrel of the Images’. During the Reformation they were translated into vernacular languages to give us Bildersturm and Bilderstürmer; a French equivalent for ‘iconoclast’, brisimage, did not survive.16 ‘Vandalism’, an adaptation from the French vandalisme, is generally associated with the French Revolution and more specifically with Abbé Grégoire, who boasted in his Memoirs of inventing it, writing in 1807–8 that ‘I coined the word to kill the thing.’ But it derives from a metaphorical use of the term ‘Vandal’, chosen from among other candidates to symbolize barbaric conduct, already in use in England by the early seventeenth century.17

Both terms have witnessed an important widening of their semantic field. ‘Iconoclasm’ grew from the destruction of religious images and opposition to the religious use of images to, literally, the destruction of, and opposition to, any images or works of art and, metaphorically, the ‘attacking or overthrow of venerated institutions and cherished beliefs, regarded as fallacious or superstitious’ (sometimes replaced in the latter sense in English by ‘radical’).18 ‘Vandalism’ went from meaning the destruction of works of art and monuments to that of any objects whatever, insofar as the effect could be denounced as a ‘barbarous, ignorant, or inartistic treatment’ devoid of meaning.19 Indeed, the reckoned presence or absence of a motive is the main reason today for the choice of one or the other term. ‘Iconoclasm’ is always used for Byzantium, and is the preferred term for the Reformation; for the French Revolution, ‘vandalism’ remains in favour, although sometimes it is offered (in quotation marks) as ‘Revolutionary vandalism’. ‘Iconoclasm’ implies an intention, sometimes a doctrine: thus Julius von Végh, for example, opposed individual vandalism to systematic iconoclasm.20 ‘Vandalism’ represents the prototype of the ‘gratuitous action’, so that a sociologist aptly described it as a ‘residual category’.21 Whereas the use of ‘iconoclasm’ and ‘iconoclast’ is compatible with neutrality and even – at least in the metaphorical sense – with approval, ‘vandalism’ and ‘vandal’ are always stigmatizing, and imply blindness, ignorance, stupidity, baseness or lack of taste. In common usage this discrimination may often be unconscious and amount to a social distinction, comparable to the one between ‘eroticism’ and ‘pornography’. (Alain Robbe-Grillet is said to have declared, with reference to the cinema, that ‘pornography is the others’ eroticism’.) But the same distinction remains true (and may not always be conscious) in scientific usage, as John Phillips neatly expressed when he wrote that ‘iconoclasm for the iconoclasts was an act far different from our later understanding of it as vandalism’.22 The polemical and performative character of ‘vandalism’ could not have been more plainly stated than in Grégoire’s proud explanation. The word aimed at excluding the ‘vandal’ – and at menacing potential ‘vandals’ with exclusion – from the community of civilized mankind, or more specifically, according to circumstances, of neighbourhood, city, nation, etc. Réau chose to write a history of ‘vandalism’ (and not of ‘iconoclasm’) for precisely this reason, and explained that ‘any attack whatever against a work of beauty . . . deserves the excommunication’ implied by this term.23

Needless to say, the origin and connotations of ‘vandalism’ make it particularly inappropriate for use in a scientific context aiming at interpretation. Moreover, even if the wilful degradation of works of art may in some cases have something in common with assaults on telephone booths, the broadening of the field of destruction attributed to ‘vandalism’ tends to refute the likelihood that the destruction of art is a specific phenomenon. In contrast, ‘iconoclasm’ and ‘iconoclast’ have the advantage of implying that the actions or attitudes thus designated have a meaning. Unfortunately, the term presents other difficulties. Even if a religious character regarding the images attacked or rejected is no longer automatically assumed, ‘iconoclasm’ does raise the expectation that attack and rejection concern images (Réau justified his rejection of it by stressing the importance of architecture), and the signified rather than the signifier; these limitations are lifted in the metaphorical sense, but it suppresses altogether artefacts as targets and introduces another limitation by regarding the critique and rejection of traditional authorities and norms only, and not that of anti-traditional manifestations.

Given this, one might think that the only terminological solution is a standard phrase like the one adopted for the title of this book. But even if the destruction of art avoids or dela...