![]()

1

DIGITAL CODES, TICKER TAPE, PUNCHED CARDS AND TELEPRINTING: ON THE ORIGIN OF DIGITALITY

There is not really a lot written about digitality or even the digital. To be sure, there is an abundance of texts, sites, blogs, dictionary entries, articles and books on digital data, digital computing, digital media or just about anything else that could use digital as an adjective. But just what is digitality if we think of it as a noun? What is digital? Even Wikipedia doesn’t help much. When I typed in ‘digital’ no Wikipedia page resulted. I got a range of possibilities, though: digital data, digital computer, digital electronics, digital media and digital signal. I even found that digital could refer to Digital: A Love Story, a 2010 indie video game by Christine Love.1 However, no helpful page of definitions, histories and other associations of the thing we call digital.

When you do start to piece together the bits that talk about digitality or the digital, you find that they tend to refer to a history, a genealogy, firmly attached to the beginning of electronic computing. If we go the formal definitional route, the Oxford English Dictionary, it seems that digitality has not yet arrived, officially, in the English language. We do find digital, however, with its uses as nouns and as adjectives. But even here in the definitive dictionary of the English language, we find digital qualifying forms of technology, most of which relates to computation or computers. There is reference to fingers and numerals below 10, even keyboards, but in the bastion of authoritative definitions, digitality seems to be firmly dependent on computation.

Histories of computing, which should shed light on digitality, are not much better. They refer loosely to the origins of the digital in Morse’s code, in the Jacquard loom and its foreshadowing of the punched card revolution of the twentieth century. Basically, anything that made a beep or punched a hole, and could carry information as a result, seemed to be a direct and self-evident forebear of the digital. But even if we accept that these beeping and hole-punching technologies of the nineteenth century inevitably led to digitality as we understand it today, which we are not going to do here except for the sake of argument, then what did all this beeping and hole-punching have to do with computation?

Of course this somewhat flippant aside is to draw our attention to what I argue are the demonstrable qualities of the digital. Here we will look at the nineteenth-century beeping and hole-punching technologies, but from a different perspective: that of what they did to develop the idea that messages, the printed word in particular, could be encoded and transmitted electrically over vast distances very rapidly; that it was both possible, and a good idea, to develop an encoding medium that allowed people to communicate written messages over wires.

Please note that in this chapter we will not discuss any of the computational technologies as forerunners, or forefathers, of the digital. In the nineteenth century there was a great deal of interest in computers, computation and algorithmic processes, but, as we will find out, these did not directly influence the digital – at least not until the mid-twentieth century. The nineteenth-century technologies we are going to explore in this chapter only dealt with these matters tangentially. It is the world of telegraphs and telecommunications – the premier technological and economic revolutions of the nineteenth century – that we will discuss.

Morse wasn’t digital

It was the new year 1825 when Samuel Morse, a portrait painter from Philadelphia in the relatively new United States, wrote to his wife, Lucretia, ‘I have just learned in confidence [that I have been given the commission], from one of the members of the committee of the corporation appointed to procure a full-length portrait of Lafayette.’2 The Lafayette referred to was none other than Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette, the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a general in the American Revolution and close friend of George Washington. Known simply as Lafayette in the USA, he was a real celebrity, and gaining the commission to paint his portrait was a considerable achievement for Morse.

Morse travelled to Washington, DC, where Lafayette was staying at the time, on 4–6 February that year, meeting with him on the 9th to begin the portrait. By all accounts, the meeting went well, and Morse and Lafayette would strike up a friendship that would last until Lafayette’s death in 1832. However, the day after Morse arrived in Washington, his father sent him an urgent letter imparting the tragic news of his wife’s sudden death. He did not receive the letter until Friday 11 February, whereupon he immediately left for the long trip back to Philadelphia.3

Today, we only have the faintest understanding of what it must have been like to communicate with our families while travelling in the 1820s. We have a vague understanding that it took a long time to get somewhere, and that communications, by letter or courier only, also took a long time. We may be surprised, when we recount Morse’s tragedy, that he and his family were corresponding with each other on almost a daily basis, albeit with the letters taking three or more days to travel the 225 km between Washington and Philadelphia. We can only imagine what it must have been like for Samuel Morse to make the three-day journey back to Philadelphia to his three children, the youngest only a few weeks old, to find his wife had already been buried two days previously.

There are two ways of thinking about this story. First, it is a common tale of a time when life expectancy, especially for childbearing women, was not long and communication over distance was lengthy. Even by the early 1800s, correspondence from Asia to North America, or Europe, would take a minimum of two months. That would be a third of a year for a letter to be sent from, say, Australia to England and a reply to return. That is, of course, if you were one of the very few people who could even afford to send a letter at all. The second way of thinking about this particular story is from Morse’s own point of view, for it was Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791–1872) who was one of the key players who would go on, over the next fifteen years, to utterly transform this situation and initiate the establishment of modern telecommunications. For Samuel Morse, our portrait painter from Philadelphia, is the Samuel Morse of Morse code fame and the single wire telegraph.

Legend has it that it was the death of Morse’s dear wife that motivated him to explore the possibility of electrical communication. There is, however, no real evidence for this, and Morse never alluded to this event as related in any way to his later work on electromagnetism and the telegraph. A more likely impetus was his meeting with Charles Thomas Jackson while sailing back from a European trip in 1832. Jackson was a geologist who had an expert knowledge of electromagnetism and was the inventor of Jackson’s electromagnet. It seems that their long conversations aboard ship sparked the keen interest of Morse, who began experimenting with electromagnets upon his return to New York. Also important was the help of Morse’s colleague Professor Leonard Gale, a professor of chemistry at New York University, who put Morse in touch with developments in telegraphy and relays in Europe. Despite having very little in the way of scientific or technical competencies, Morse managed, by 1837, to create a working telegraph that could transmit a message over 16 km.

This achievement was not his alone; such achievements never are of one person. Morse was a driving force and seemed to have a knack for building collaborations with really talented people. The development of the Morse key, for example, went through several working versions, each one improved by people Morse was working with, or who were working for him. Critical improvements were made by his hired assistant, Alfred Vail. Batteries and key relay technology were provided by the collaboration with Professor Gale. When Morse actually won a grant from the U.S. Congress to run a test telegraph from Baltimore to Washington, DC, the telegraph which is now portrayed as the ‘1st Telegraph’, he employed a farmer from upper New York State to lay the cable in the ground using a plough. The project faced disaster when Morse realized that the cable in the ground would not work over more than 10–12 km. The day after the test, which demonstrated that Morse would soon be bankrupt, the farmer, a Mr Ezra Cornell, intentionally drove his plough into a rock, a pretence that gave precious time to devise a solution. Cornell’s solution was to string the wire between posts on glass insulators above ground. The wire would soon transmit what was the first electric coded message, ‘What hath God wrought!’, sent by Morse from the Library of Congress to Alfred Vail in Baltimore on 24 May 1844. Ezra Cornell would go on to dominate the telegraph industry, ultimately forming, with partners, the Western Union company and donating a large portion of his fortune to found a university in his home town of Ithaca, New York.

Of course, it wasn’t really the telegraph device that made Morse’s name, though the basic design of the Morse key remains in use even today. The key invention of Morse’s telegraph was a code, Morse’s code. Morse’s first code, one that he devised soon after his opportune return from Europe to New York, was a code to transmit numbers. The idea, which was not uncommon at the time, was to create a dictionary of common words and phrases, each indexed with a number. As the telegraph would be expensive and transmissions not very fast, the idea was to transmit the numeric codes, which would be looked up in a dictionary at the receiving end and then written down. It was Morse’s assistant, Alfred Vail, who saw both the potential of an alphanumeric code, a code of both letters and numbers, and actually devised what we know today as Morse’s code – the varying sequences of dots and dashes.

The key advantage of Morse’s telegraph, unlike competing telegraphs in Europe, such as the Cooke and Wheatstone system which had been installed in London just a few years before, was that it offered a relatively rapid and easily learned code of letters and numbers for any form of message to be sent between operators electrically over a wire. Another advantage was that operators did not have to understand the message, or even the language, that was being transmitted. They simply had to correctly interpret the signal and transcribe the characters.

Original model for Morse’s code, from Alfred Vail’s notebook of 1837.

The relative simplicity and ease of Morse’s telegraph meant that, within a mere fifteen years, it was the standard telegraph system for most of the world, except for the British Empire, which kept the Cooke and Wheatstone system until the early twentieth century. The expansion of telegraphy and telegraph systems was extraordinarily rapid. The number of messages sent by Western Union alone was already 5.8 million in 1867, but rose to a staggering 63.2 million by 1900. When Samuel Morse died in 1872, there were more than 200,000 miles of telegraph wire across the United States alone, and much of the world was already joined by undersea cables.

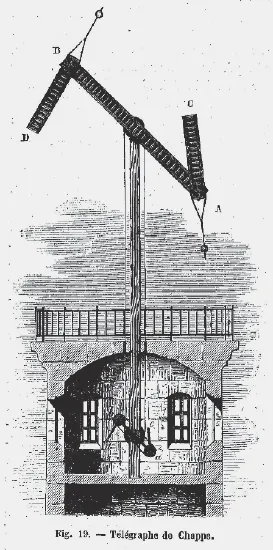

Despite the extraordinary success of the Morse system, and its survival throughout the twentieth century – largely owing to its applicability for radio communications – it did not spontaneously spring into life from a mere idea. From the end of the eighteenth century onwards, many developments took place in what we would call coded communications at a distance. Flags had been used to send very simple messages between ships for centuries, and are still used today, but a means to send simple messages over long distances was needed and several systems were devised in the eighteenth century. One of the most successful was the Chappe telegraph. Designed by Claude Chappe for Napoleon’s army, the Chappe telegraph was a series of line-of-sight semaphore buildings, built with a controllable beam and two arms. A code of 92 positions allowed for 8,462 coded words to be transmitted between stations. The words would be coded into combinations of the 92 positions of the arms, which would be repeated down the line to be translated with a code book at the destination. This was certainly the inspiration for Morse’s first idea for sending numeric codes using a code book, or dictionary, as many such systems existed by the 1830s.

The Chappe telegraph was extremely successful – a famous abuse of the system features in Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo (1844) – and continued in use well into the nineteenth century. Semaphore systems for communicating with ships at sea, from port, continued until the advent of ubiquitous radio communication in the mid-twentieth century.

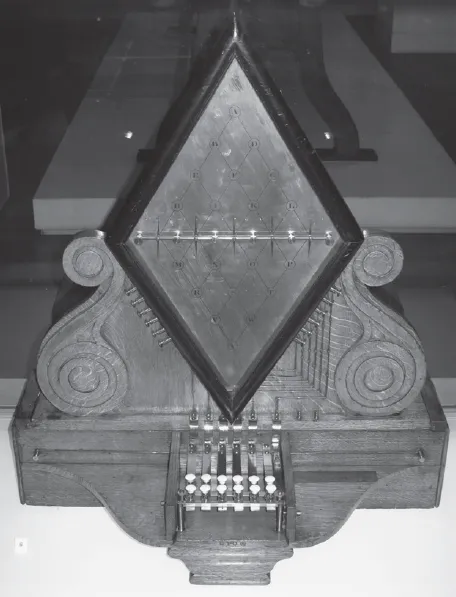

There were also other telegraphs in development, or even in use, in the early nineteenth century. I have already mentioned the Cooke and Wheatstone system. This was a two-dial telegraph which needed four wires, thus increasing the cost, yet the British used it throughout the empire until the end of the nineteenth century. There were also many improvements made to Morse’s initial system. As the telegraph industry exploded in the mid-nineteenth century, so did the need for new and improved telegraph technology. Most of this innovation was in the form of better and more reliable batteries, but transmission and reception devices were also improved. One area that received much attention both in the United States and Europe was the ability to record messages automatically.

| Workings of a Chappe telegraph, 19th-century engraving. |

Many histories of the telegraph and telecommunications identify Morse’s telegraph, and particularly Morse’s code, as the forerunner of digital communications. However, Morse’s code is not a binary, or digital, code. It is what we call a quinary code, as it is based on five elements:

Cooke and Wheatstone four-dial electric telegraph.

1short mark, dot or ‘dit’ (·)

2longer mark, dash or ‘dah’ (–)

3intra-character gap (between the dots and dashes within a character)

4short gap (between letters)

5medium gap (between words)

The major problem with such codes, like the Morse or even the Chappe and semaphore codes, is that they are very hard to interpret mechanically. As they need to be sent by an operator, each with their own ‘hand’, or style, the receiver must be equally skilled in ‘reading’ the transmission. There are...