![]()

ONE

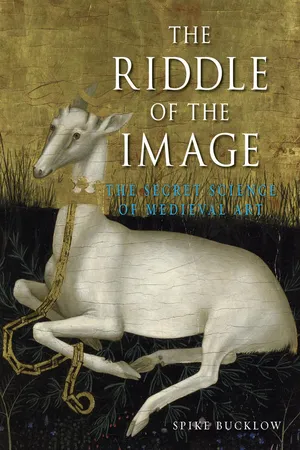

Lead White: Strange Matter

The illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings explored in this book were high-end cultural goods. Their position in the economy of medieval Europe was similar to that of today’s electronic goods – people can survive without them, but they have their uses, including displaying images and status. And, like TVs, computers and mobile phones, illuminated manuscripts and panel paintings were also technological products.

Modern hi-tech consumer items are made by complex chains of specialized activities. They are obviously hi-tech because we can use them without knowing anything about their manufacture, and what goes on behind the screen is a mystery that we do not need to understand. However, modern attitudes towards the technology that underlies paintings are quite different. Most of us painted at school, so, superficially, the process seems quite familiar – the only surprise is how the Old Masters did it so well.

No single person on earth could ever possibly make a TV, computer or mobile phone from its raw materials. But a single person could easily make a painting from scratch if they wanted. They could collect ores, build a furnace, smelt metals, make axes and knives, and then cut down a tree for a panel, or kill and skin an animal to prepare velum. Or they could make a plough, till soil, grow flax, spin linen, build a loom and then weave a canvas. If they wanted to use paper, they could make a sieve, find a pond or divert a stream and use wood pulp or waste cloth. They could prepare the panel, canvas, velum or paper with glue made from animal skin, wheat starch or old cheese. They could make brushes from sticks and squirrel or hog hair, or make quills from feathers. Then they could make a paint medium by bleeding resins from a tree, squeezing oil from flax seeds, or simply by collecting eggs from a hen. Finally, for pigments, they could pick up different coloured earths, grind, wash and maybe burn them, char bones or twigs, and extract colours from plants and insects.

One person could do all of these things and then combine the products to make a painting. Of course, they might be better at some tasks than others, but none is beyond a single individual and countless historic manuals describe each of the activities in great detail. It follows that people who looked at Old Master paintings during the artists’ lifetimes would have known much of what went into creating the images. Today, however, paintings are in museums and galleries, and are completely divorced from everyday experience. So, sadly, the origins of Old Master paintings have become almost as mystifying as the origins of digital images. A whole dimension associated with the artist’s materials and methods has been lost because even our childhood encounters with painting in school involved just being given paint, paper and brushes by a teacher. Modern materials are not prepared – they come from shops.

Materials are necessary for making images and, whether or not we paint, we all create images – be they careful, careless or carefree – by choosing particular clothes, haircuts or make-up. Everyone makes judgements based on the images that they see. Image has vast cosmological significance, which is why make-up and some surgical procedures are called ‘cosmetic’. Today, the cosmological significance of materials is largely forgotten but, once recalled, it can provide a powerful way of understanding art. Yet before painters could make art, they had to make their materials. So this chapter focuses on a modest material – lead white – which was an essential ingredient of every great European painting, right up to the mid-twentieth century. It happens to be the main ingredient for paint used in depictions of flesh, and it is no coincidence that it was also used as make-up to lighten living flesh for thousands of years (illus. 1). Painters may have made this particular pigment themselves, but they might also have bought it ready-made.1 In this case, they would usually have gone to the apothecary, where it was also sold as an ingredient for cosmetics and medicines.2 These crossovers helped make artists’ materials familiar to non-painters.

| 1 Westminster Retable, detail (see illus. 33). Lead white provides the colour for St Peter’s hair, eyes and flesh, as well as the highlights of his robe and its black-and-white ermine. |

Artists and doctors were also connected in the person of St Luke, patron saint of both, and the vocations were associated for millennia. For example, in the early sixteenth century the successful painter Lucas Cranach bought his local apothecary as an investment. He employed professionals to run it, but he also had a personal interest in alchemy, an integral part of the apothecary’s art. A little later, in the mid-sixteenth century, when the Academy of Drawing was set up in Florence by Cosimo de’ Medici on the instigation of Giorgio Vasari, a petition was made so that the painters could be released from the city’s Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries.3 The composition of paintings was informed by the pharmacological properties of pigment right up to the seventeenth century.4

In the seventeenth century, the relationship between painters and physicians was in decline, although the two vocations were still in the same division of the Haarlem Guild of St Luke.5 A manual that discusses Rubens’s and van Dyck’s painting techniques was written by London’s leading physician, Sir Théodore Turquet de Mayerne, doctor to kings.6 (About a century later, the connection between painters and physicians endured in William Hogarth’s involvement in establishing London’s Foundling Hospital.7) About 400 years earlier, a doctor had been among a fictitious group of pilgrims who went to Canterbury. Chaucer said of him

No one alive could talk as well as he did

… The cause of every malady you’d got

He knew, and whether dry, cold, moist or hot.8

‘Dry, cold, moist or hot’ are the four qualities that relate to the four elements – cold and dry earth, cold and wet water, wet and hot air, and hot and dry fire. A balance of these qualities results in good health, whereas imbalances led to a variety of illnesses. Exactly the same ideas governed artists’ techniques. So the ideas behind artists’ techniques were quite familiar to the people who commissioned and enjoyed paintings, if they had any interest in their own health.

However, the world has changed and the images that were created centuries ago are the product of beliefs that are now quite unfamiliar. Today, some of those images – and much of what went into them – might appear, to use Shakespeare’s words from Hamlet, ‘wondrous strange’. If we are to appreciate them fully, then we must follow Hamlet’s response to strangeness, which was ‘therefore as a stranger give it welcome’.9

Strangeness

Hamlet recommended an open mind in the face of the unfamiliar. But Shakespeare’s phrase owes much to an ancient theme: the traditional obligation to offer hospitality to strangers. Shakespeare knew this tradition from at least two sources – the Bible,10 and classical myth, where it occurs as the concept of xenia. Xenia, or hospitality, features in the Odyssey, for example, when a swineherd, Eumaeus, calls his ferocious dogs off a passing beggar. Eumaeus kills a pig to feed the hungry traveller, they share some wine and tell stories, and the ‘good host’ then gives his ‘strange guest’ the ‘portion of honour’ after first offering meat to Zeus, the god who protects strangers. (The ragged old man turned out to be the swineherd’s long-lost master, Odysseus, but he maintained his deception and enjoyed more hospitality as a stranger.11) The obligation to offer strangers hospitality is a convention that expresses the bond of solidarity between insiders, such as those defined by the ties of blood or creed, and outsiders who do not belong to a particular family or faith. Now, insiders and outsiders are the inevitable result of any grouping, such as the insiders who know how to paint and the outsiders who do not. In later chapters it will become clear that the concept of xenia can help to unravel the riddles presented by images.

Hamlet’s ‘welcome of a stranger’ was a response to his father’s ghost, suggesting a bond between those in the natural world and those of the supernatural. Indeed, Hamlet famously follows his advice about open-mindedness by saying, ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’12 Another of Shakespeare’s characters, Duke Vincentio in Measure for Measure, reinforces the message, advising against having ‘a stubborn soul / That apprehends no further than this world’.13

In order to appreciate the power of images in illuminated manuscripts and on panel paintings, the modern viewer has to be hospitable towards those aspects of the painter’s world that appear strange. A medieval image possesses something like the strange power of a relic. A painting may not contain venerated remains – channelling the spiritual powers associated with a saint – but the whole world back then was God’s creation, and every part of it was charged with spiritual power. Every colour in a painting had the potential to offer its social and spiritual significance to the finished image. In the Middle Ages, European paintings contained ultramarine blue made from lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan, vermilion synthesized by alchemists searching for the philosopher’s stone, and gold purified from African mines or recycled from ancient treasures.14 But even the most modest, home-grown colours had stories to tell and meanings to give to the best paintings.

This chapter looks at a pigment that is found in every one of the images explored in following chapters. Some aspects of that pigment might seem strange to the modern eye.

Making lead white

Lead white – known from classical times as ‘ceruse’ and called ‘basic lead carbonate’ by modern science – is rarely found in large amounts in nature. In the first century, Pliny said that most of it was manufactured.15 It was among artists’ materials found in the ruins of ancient Ur dating to around 3000 BC.16 Indeed, its manufacture is mentioned in cruciform tablets of about 1700 BC retrieved from Assurbanipal’s ruined library at Nineveh.17 Theophrastus described its manufacture 300 years before Christ.18 Later, Vitruvius described how it was made in Rhodes, where the natural version had once been mined, and it was the painter’s most important artificial white pigment until the mid-twentieth century.19

Of course, there were variations on the theme, but the way of making it changed relatively little for 4,000 years and was described regularly in European manuscripts. The early ninth-century artists’ manual Mappae Clavicula contains several recipes, and, 300 years later, ‘Theophilus’ (an anonymous German or Flemish monk) gave a full and detailed account of how to make the pigment.20 He said that you should take sheets of lead, place them in an oak chest, sprinkle them with vinegar and urine and bury them under horse dung for a month, then dig up the lead and scrape off the white-coloured rust.21 I have followed his recipe: it works, and it is as easy as it sounds (illus. 2).

Urine and horse dung might sound rather unlikely chemicals for the manufacture of a synthetic pigment, but they were standard alchemical ingredients. They are among the things mentioned in The Canterbury Tales when, bemoaning his fate in the service of a canon who was interested in alchemy, the Yeoman listed

Our urinals, our pots for oil-extraction,

Crucibles, pots for sublimative action,

Phial, alembic, beaker, gourde-retort,

And other useless nonsense of the sort.

...