![]()

1

The Theatre of Nature, 1723–50

Philosophers are made, not born – at least, according to Smith. As he writes in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a philosopher and ‘a common street porter’ might display ‘the most dissimilar characters’, but the apparent differences in personality, income and talent result ‘not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education’. As children, he notes, it would have been hard for their respective parents or playmates to see any difference between them. They were two boys like any others. One boy did not become a philosopher because of his extraordinary brain, nor did the other become a porter because he had been born with especially strong muscles suitable for carrying things around. The philosopher might subsequently deny this natural resemblance, insisting that he had become a philosopher because he was more intelligent than the porter. But that is just vanity.

It also reflects our desire to identify an aesthetically pleasing efficiency or fitness (what Smith calls ‘propriety’) in the way our society assigns men and women to different ranks and professions. It does not just hurt our pride, after all, to be told that our choice of career was the result of a series of accidents, chiefly of birth (in Smith’s day, as in ours, the main determinant of a child’s future income was its parents’ income, not its own ‘genius’ or intelligence). It induces anxiety by suggesting that our society is not as ordered as we desire it to appear. We like to think that the philosopher and the porter rightly belong in their respective positions in society. Together this vanity and this appetite for systems lead us to confuse causes with effects. ‘The difference of natural talents in different men is, in reality, much less than we are aware of,’ Smith notes, ‘and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much as the cause, as the effect of the division of labour’ (WN, 28). The porter has strong muscles because after boyhood he was set to work carrying things. Had he been given a different education and set to reading books, he would not have developed the muscles that made him appear a born porter. In considering Adam Smith’s early life, it does indeed seem as if ‘habit, custom and education’ played a greater role than ‘nature’.

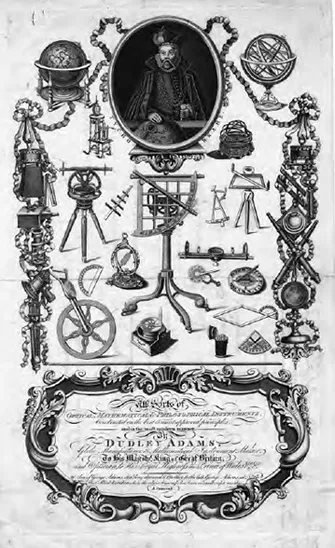

An eighteenth-century trade card advertising the scientific instrument maker Dudley Adams.

Adam Smith was born in the summer of 1723 in the Scottish port town of Kirkcaldy, which lies on the east coast, on the opposite side of the river Forth from the Scottish capital, Edinburgh. Today Kirkcaldy has a population of 46,000, largely supported by linoleum production. In Smith’s youth, however, its population was much smaller, and it may well have seemed as if the town’s heyday was long past. Kirkcaldy had won the right to hold a market in 1334. It gained administrative independence in 1644 when King Charles I made it a royal burgh. This status released it from the financial burdens and legal jurisdiction of the local feudal landlord, the abbot of Dunfermline. Elsewhere in Scotland, notably among the Highland clans, this medieval system of feudal land tenure continued into Smith’s day and beyond. Once free from these feudal ties, Kirkcaldy expanded as a port and trading centre, thriving on the North Sea trade, especially with the Netherlands. In the eighteenth century, however, the commercial tide turned from east to west, from the North Sea to the Atlantic, and from the trade in salt and coal to the trade in tobacco, sugar and other products exported to Glasgow (on the west side of Scotland) from Britain’s rapidly expanding colonies in North America.

The 1707 union of the monarchies of Scotland and England also led to increased taxation. Seven years later the British parliament sitting in London placed a German princeling (George, Elector of Hanover) on the British throne. King George I had few ties to Britain and did not even speak English, but was at least Protestant, like the vast majority of his new subjects. In placing George on the throne Parliament had had to jump over many other men with far stronger claims, but who were disqualified on the grounds of being Roman Catholic. The lead claimant (or pretender), James Edward Stuart, led his Scottish supporters in a revolt in 1715. Though unsuccessful, this insurrection brought further disruption and taxation to Kirkcaldy. Between 1655 and 1755 the population more than halved, to 2,296.

Smith would live to see this process begin to go into reverse, however, as Kirkcaldy turned from trade to manufacturing. Local supplies of timber and the port made shipbuilding a profitable endeavour, and nail-making was an established industry. Flax was imported from the Netherlands and the Baltic for working into linen, not in large mills but rather through cottage industry: under the ‘putting out system’, tenant farmers contracted with linen ‘factors’ (manufacturers) to produce linen on a piecework basis, being supplied with flax which they worked into linen on a loom at home. Annual Scottish linen output increased from 5.5 million yards to 13.5 million between 1746 and 1771.1 Later on, stocking manufacture was introduced to the area. The creation of linen floorcloths in the following century laid the foundations of the city’s linoleum boom. The immediate surroundings of Kirkcaldy were a mixed economy; alongside sheep-herding, forestry and agriculture there was proto-industrialization (the putting out system), industrialization (the nail works, the shipyards) and both local and international trade. What Kirkcaldy lacked in fine architecture it more than made up for in the range of economic activities it supported. Smith’s father was well placed to observe all this activity – indeed, it was his duty to do so – as a Kirkcaldy customs officer.

Unfortunately, Adam Smith never knew his father. Adam Smith senior, at the age of 44, died five months before his son was born. There were no siblings, apart from a half-brother, Hugh, the product of Adam Smith senior’s first marriage. Hugh was fourteen years older and probably also worked in the customs service – the customs were something of a family business, with other Smiths working for the customs in Alloa, Montrose and Aberdeen.2 Hugh and Adam had little contact. Even if they never met, the two Adam Smiths’ careers were surprisingly similar: both served as customs officials and both relied on a network of aristocratic patronage. The elder Smith was secretary to the third Earl of Loudoun, whose support doubtless helped him secure his appointment in 1714 as Controller of Customs in Kirkcaldy; other members of the Smith family worked in a similar capacity for the Duke of Argyll, an even more powerful Scottish landowner. Marriage to the daughter of another landowner and Member of Parliament in 1720 further boosted Adam Smith senior’s fortunes and network of contacts. Young Adam Smith was set to inherit a comfortable estate as well as these contacts, who served as guardians of his property until he came of age and was legally able to administer it himself.

‘Habits and customs’ of patronage thus linked father and son in service to a particular segment of the traditional Scottish landowning aristocracy. These earls and dukes supported the union of 1707 rather than the Jacobites. The Hereditable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act of 1746 stripped them and their peers of their remaining legal powers. But union with England did not just take, it also gave. In a process of co-option by the monarchy these noblemen’s support of the Union was rewarded. The British monarchy compensated them with new forms of patronage, with powers to nominate their retainers to new state offices in the customs service, in the courts and elsewhere. These noblemen’s dress, accent and manners gradually became more English, and some settled south of the border on a near-permanent basis. Many looked to England for the resources in capital and know-how they felt were necessary for the economic development of Scotland. By the 1770s the obscure dialect, dress and particularly the poetic traditions of the Highlands were beginning to appear quaint and desirably authentic, laying the foundations of that romantic image of Scotland that underpins today’s tourist industry. In the 1720s, however, they simply seemed barbaric and threatening (because of their Jacobitism). A new agenda of ‘Improvement’ was born, which sought to strike a balance between innovation and a patriotic respect for native institutions. Both Smiths played a part in this project, which they certainly would not have seen as compromising their Scottish identity.

But alongside ‘habits and customs’ such as patronage and patriotism, ‘education’ was equally important in shaping the younger Smith’s development. Smith’s mother Margaret would have taken the first steps, forging a mother-son bond that proved exceptionally strong. In 1723 Kirkcaldy’s town council had built a two-room school, which remained in use until 1843. The system of parish schools found across Scotland as well as the universities reflected a widespread respect for education, sufficient to lead almost all Scottish parents to make the financial and other sacrifices (such as the loss of their child’s labour – a valuable commodity in itself) necessary to send their children to school for a few years. In school Smith not only learned reading, writing and arithmetic but Latin and some Greek. In The Wealth of Nations Smith argues that this grammar school curriculum, which saw ‘the children of common people’ taught ‘a little smattering of Latin’, should be replaced with one with space for ‘the elementary parts of geometry and mechanicks’. As he noted, few trades demanded Latin, whereas ‘there is scarce a common trade which does not afford some opportunities of applying to it the principles of geometry and mechanicks’ (WN, 785–6).

Latin and Greek allowed the young Smith to read classical philosophical and historical texts in the original language. Indeed, that was the whole point to teaching these dead languages: to gain access to a classical world whose art and rhetoric were held to embody the greatest that human culture could achieve; whose philosophers, statesmen and military leaders eclipsed anything the modern world had to offer. Having recovered this culture in the Renaissance of the fifteenth century, in the eighteenth century western Europe was only just beginning to think that the moderns might in fact outdo the ancients. Smith may have been exposed to the thought of Stoic philosophers while still at Kirkcaldy: an eighteenth-century edition of the Encheiridion (Handbook, compiled by Epictetus’ pupil Arrian) survives with Smith’s name on it, and may date from his youth there.

The Encheiridion teaches us to rid ourselves of the fantasy that we have power over our bodies, possessions or other external things, when we only have power to control our inner state. We achieve true freedom or tranquillity (in Greek, ataraxia) through self-knowledge, silencing the desires that threaten to enslave us, and achieving command over our emotions (apatheia). We are then free to act as ‘a member of the vast commonwealth of nature’ (TMS, 140). The Stoics were often contrasted with the Epicurean school, which also emerged in third-century BCE Greece, but which Smith would have known mainly through the writings of the first-century BCE Roman poet Lucretius. Epicureans teach that humans achieve ataraxia through the pursuit of pleasure. Though the word ‘epicurean’ was and is often used to refer to individuals who see pleasure as the highest good (hedonists) and supposedly indulge in orgies of various kinds, true Epicureans recognize the pains of over-indulgence (hangovers, STDs, self-loathing) and hence seek pleasure in moderation. They seek a form of government founded on an ‘original contract’, which protects the members of society from harm and allows them to pursue pleasure.

Epictetus, Lucretius and other great philosophers of antiquity were lifelong companions for Smith, and university gave him further opportunities to study their teachings. In 1737 Smith left his hometown and entered the University of Glasgow. It was not unusual for boys to attend university at such an age. Thanks to the aforementioned trade in tobacco with the colonies across the Atlantic, Glasgow was a growing city, albeit half the size of Edinburgh, with a population of 23,500 in 1755. Today the university is based in a Victorian suburb of the city, in a large Gothic Revival complex. In Smith’s day the university was in the city’s heart, built around two Georgian quadrangles with a pleasant garden. Here Smith remained for three years, attending lectures on logic, Latin, Greek, moral philosophy, natural philosophy and mathematics. The majority of these would have been delivered in Latin, and all would have commenced with a prayer. Until 1726 the university smacked of a seminary, primarily intended to train priests for ordination in the Church of Scotland. The creation of new chairs in logic, moral philosophy and natural philosophy in that year formed part of an attempt to broaden the university’s appeal, attracting the sons of the merchant and aristocratic elite, for whom paying lecture fees was no hardship but who did not plan to spend their lives in the pulpit or the law courts. Rather than providing an apprenticeship for a guild of priests or lawyers, the Scottish universities increasingly sought to provide an education, a set of tools for thinking and discussing. This learning was defined as ‘polite’ rather than narrowly ‘useful’.

We know very little about Smith’s first Glasgow period, but he clearly learned much from the professor of moral philosophy, Francis Hutcheson. Born in County Down in Northern Ireland, Hutcheson had come to the University of Glasgow in 1710, aged sixteen. After establishing an academy in Dublin and publishing his Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (1725) he returned to Glasgow to take up his chair in 1730, delivering his inaugural lecture on ‘the social nature of man’. Though this lecture was delivered and published in Latin, Hutcheson otherwise fully supported the aforementioned project to modernize the university’s curriculum. He was the first professor at Glasgow to switch to lecturing in English and was rewarded with large audiences. But his ‘New Light’ views on the innate goodness of man angered orthodox Presbyterians. He seemed to suggest that humans could work their own salvation without turning to Jesus Christ, God’s only son, who had been sent to bring humans salvation by offering himself as the one perfect sacrifice for their sin. A year into Smith’s time at Glasgow, Hutcheson was hauled before the Church elders and charged with deviating from the 1647 Westminster Confession, the basis of Church of Scotland orthodoxy. Though he was not convicted, it doubtless provided his student Smith with a lesson in the need for public instructors to exercise professional prudence. In 1743 Hutcheson’s ally, professor of divinity William Leechman, was prosecuted for heresy, using information gathered by student informants.

The University of Glasgow in Smith’s day. John Slezer, ‘The Colledge of Glasgow’, engraving from Theatrum Scotiae (1697).

In his Inquiry and his inaugural lecture Hutcheson tackled those philosophers and moralists who saw humans’ passionate nature as making ‘the state of nature’ a miserable state of wanton violence. By ‘state of nature’ these thinkers were referring to a pre-social state, to the behaviour of humans before certain rules were laid down (in an ‘original contract’) and they entered a properly regulated society. For Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651) human life in this state was ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. Hobbes in turn influenced Samuel von Pufendorf, who, while little read today, was one of the most influential philosophers in early eighteenth-century Europe. Pufendorf’s De officio hominis et civis (1673) was translated into English in 1691 by Andrew Tooke as The Whole Duty of Man According to the Law of Nature. At least 145 other editions and translations appeared in the years to 1789. Pufendorf argued that humans acted virtuously only out of fear of divine punishment and the expectation of divine reward. Were this God-focused hope and fear to be removed, ‘no Man wo...