![]()

HISTORY

![]()

1 Before Prussia (until 1701)

When the ice receded, it left a shallow glacial valley strung with lakes and bogs, with peat and mud deposits. The higher ground was a mix of clay with lime. Almost everything else was sand. It is the same sand driven later by wind down the streets, covering piles of rubble after the Second World War. Or that today is the bane of construction crews still rebuilding a city reduced to the ground. More than a third of all trees lining today’s city streets are lindens, which can grow in sand and loam. Turn on your tap in Berlin and the water is unusually hard, having filtered through the lime. Even the ancient name of Berlin comes from this shifting landscape: the Slavic Brlo means a dry place in a bog.

This etymology hints at yet another aspect of Berlin’s origins, the fact that ‘Germans’ did not arrive here in numbers, to displace the Slavic ‘Wends’, until the rule of Albrecht the Bear, who invaded from Saxony (the Slavic world is still not far away, with the Polish border today only 50 km as the crow flies). ‘The Bear’ declared himself the Margrave of the Mark Brandenburg, the region surrounding Berlin, in the middle of the twelfth century. The phonetic, though not etymological, association of ‘Berlin’ with Bär (or bear) might be the reason the city adopted the animal as its heraldic beast by the fifteenth century.

Brandenburg is a basin, recognizable as soon as you pass into it by train from the south, carved out by the ice sheet, and distinguished from the more temperate Central Europe by its relentless flatness. But it also has softness, from what appear like endless forests, curving around the lakes. They make Berlin seem stuck in some verdant biosphere in midsummer when one peers from any gentle rise over the otherwise sheer landscape. Today, at the entrance of the exhibits of the German Historical Museum, there is a large-scale photograph of these woods. If you stand at an angle the ‘Germans’ appear superimposed in hologram, clothed in medieval garb: braided cloaks, woollen tunics, linen shirts or women’s long shifts. These people – defined more by their landscape, local culture and family connections than by anything they would recognize as ‘Germanness’ – established settlements at that dry place in the marsh, and built a bridge where the Spree river narrows ever so slightly.

Two market towns, called Berlin and Cölln, eventually faced one another, the latter located on an island in the river, now the Museum Island. But how early is a matter of debate – neither one of these small communities was significant enough to be dated by city charter. And the first times Berlin and Cölln are mentioned in writing, in 1244 and 1237 respectively, they appear in tax and administrative documents referring to the same person, which makes one wonder how distinct the two entities were in the early thirteenth century. Cölln so lacked its own civic identity that it took its name from somewhere else, Rheinlanders perhaps having named it after the great city with Roman origins in the West. And we know Berlin was tiny compared to nearby settlements, like Spandau, now just a Berlin suburb. When looking at the twelfth-century model in the Märkisches Museum, one sees that Spandau was just rows of rudimentary shacks surrounded by a timber wall. But the insignificance of Berlin-Cölln has not prevented civil authorities, as a matter of pride, from celebrating an exact founding date. The discovery of an oak plank from 1183 was heralded by the City of Berlin in 2008 as the first indication of settlement, making Berlin 54 years older than previously thought.

It was only in the late thirteenth century that Berlin-Cölln grew in wealth and numbers. It did so by taking advantage of its location. The two market posts flourished in the trade of fish and textiles from Flanders. By damming the Spree, the clever early Berliners forced traders to stop and sell their wares in the city. The crossing of Mühlendamm between Berlin and Cölln was so named because it was the location of water-powered grain mills. Focusing on these waterways, however, is only part of the story, as Berlin was also an important highway junction on both the east–west and north–south axes. Growing wealth brought with it the need for civil administration, and two councils were established that cooperated, facing each other across the long bridge. Today’s City Hall is situated at the same location as Berlin’s first authority. Many historians emphasize the fact that Berlin started as a divided city, but here we get ahead of ourselves. These towns were of course not under separate ideological systems, as Berlin would be in the mid-twentieth century. Cölln eventually joined Berlin administratively in 1307, in a town now of several thousand surrounded by a wall and gates. The Stadtmauer, or city wall of Berlin, endured in different versions, and increasing heights, in circumference around Berlin and Cölln island until the building of the much bigger Customs Wall in 1734. Remains of the early wall can be seen on Littenstrasse, not far from Alexanderplatz. Nearby are the medieval Nikolaikirche, where a Romanesque stone church once stood in the thirteenth century, and the ruins of a Franciscan monastery from around 1250 at Grunerstrasse.

St Nicholas Church (Nikolaikirche), 13th century.

From a beginning when we have a mercantile people profiting mostly off the goods that pass through a harsh landscape – rather than trying to soak their living out of the poor sandy soil – we now shift into a period of expansion. It would take the Hohenzollern family to shape this space and make it imperial in character. How striking that this dry place in a mucky mix of water and loose banks would become the capital of Europe’s largest and most troublesome power, a city at times feared and despised. Perhaps it is worth reflecting that only such a poor upstart of a city, this latecomer capital on a swampy plain, without natural boundaries in any direction, would need to remain so much on the offence.

It is remarkable that one royal house, the Hohenzollern, ruled Berlin for more than half a millennium, from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. But they were originally considered parvenu conquerors who had come to the city from the south and acquired Brandenburg only because the House of Luxembourg had defaulted on its debts. Their family castle at Zollern was hohe, or ‘high’, because it was located in the Swabian Alps, a landscape alien to the flatlands of the north. Their desire to build a palace in Berlin was not welcomed by the locals, who were unwilling to cede the power of their councils on the long bridge. Friedrich I (1371–1440) left the job unfinished for his successor, Friedrich II, the Irontoothed (1413–1471), who ran into trouble when the locals vandalized his efforts by flooding the island’s building site in 1448. Having already taken Berlin out of the Hanseatic League, he diminished civic power further by having the councils torn down; the piecemeal construction of the palace then continued for almost three hundred years. The struggle of a liberal, mercantile city population at odds with its conservative imperial rulers is a theme that can be charted even into the twentieth century. The later Baroque iteration of the palace – which was finished in 1716, damaged in the Second World War, then razed by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) – is now being rebuilt, much to the ire of many Berliners for whom it represents the ills of Prussian authoritarianism.

Remains of the medieval city wall on Littenstrasse.

By the sixteenth century, Berlin had 10,000 inhabitants, and its ruler Joachim II Hector (1505–1571) was determined to increase his royal trappings: a hunting palace in Grunewald, to the west, connected to the area around Berlin by a wooded avenue (the Kurfürstendamm, which is now Berlin’s most luxurious street). Too much time spent outside Berlin – at Grunewald and elsewhere – hunting instead of governing had unexpected consequences for the Elector. The floor of the country retreat of Grimnitz gave way one evening under him and his wife. She was impaled on the antlers of his hunting trophies below as he hung precariously from the beams. Although she survived the fall, her deformity gave him the excuse to set up with his mistress.

Ruins of the 13th-century Franciscan cloister, Grunerstrasse.

The Baroque Zeughaus (Arsenal) of 1695, home of the German Historical Museum.

Although Joachim II had promised his father to remain Catholic, he received Communion according to the Lutheran rite on 1 November 1539. Town and crown, however, would soon be further divided. Elector John Sigismund (1572–1619) converted to Calvinism, even though the majority of his subjects remained Lutheran.

Friedrich Wilhelm (1620–1688) consolidated Calvinist rule. It was the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), fought initially between the Protestant and Catholic kingdoms of Europe and resolved by the Treaty of Westphalia, which would have a defining influence on his reign. Brandenburg had been a battleground, and marauding soldiers still terrorized its lands. The young man of 23 returned to Berlin in 1643 to see his city in ruins. The population had been halved by war and plague, leaving it in a ‘zero hour’ (Berlin would have another). The devastation had a lasting impression on him, and he was determined to rebuild, keep the country on the offensive and raise a professional army. His rule saw an expansion of territories: the landlocked Mark Brandenburg, and islands of dependence to the west, absorbed a huge swathe of contiguous sea-coast in Pomerania in 1648, to add to the eastern Baltic Duchy of Prussia, which had been inherited by the Hohenzollerns in 1618. He earned the title ‘Great Elector’ through a series of military victories towards the end of the seventeenth century: at the Battle of Warsaw in 1656, and when routing the Swedes’ so-called invincible army at Brandenburg in 1675. By the end of his rule, his lands had a standing army of 20,000. With the Great Elector, one can see the foundations of the Prussian military state. Having experienced the trauma of being Europe’s battlefield for thirty years, Prussia would counter its vulnerability by investing heavily in armed protection.

Early 20th-century view of what was Cölln.

In Berlin, Friedrich Wilhelm’s urban renewal progressed with the building of a long avenue planted with lime trees and called Unter den Linden, leading from the royal palace to the location of what would be the Brandenburg Gate. Improvements in public infrastructure included building primitive sewers, cobbling streets, installing street lights and banishing barns outside the walls, as a fire risk, to the Scheunenviertel, or ‘Barn District’. Having studied among his co-religionists in Utrecht, the Netherlands (a land, of course, that was influential in the seventeenth century), he took from there some ideas for how to manage the problem of Brandenburg’s bogs and flooding by copying the canal system, building a series of waterways crossed by Dutch drawbridges between 1669 and 1671.

The Great Elector’s allegiance to Calvinism, however, is best observed in his response to a wave of émigré French Protestants. In 1685, the Edict of Nantes, which had resolved the Wars of Religion in France in 1598, was revoked. The Great Elector, in solidarity with his Calvinist co-religionists, eager to repopulate Brandenburg-Prussia after the wars, proclaimed the Edict of Potsdam, or of Tolerance, the same year. It allowed freedom of religious practice (Catholics, mind you, were not invited) and gave immigrants tax-free status for a decade. Twenty thousand of them would find their way to Brandenburg, meaning that almost a quarter of the population of the city was French-speaking by 1700. In the same spirit, Berlin would later host, in the eighteenth century, thousands of Bohemian Protestants who were followers of Jan Hus in exile.

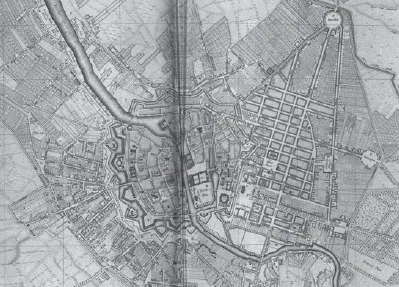

Berlin map from 1757, showing the centre divided by the river Spree.

The other major group that arrived as part of Berlin’s ‘imported bourgeoisie’ were the Jews. There had been flickers of Jewish life in Berlin before the seventeenth century: they had been subject to pogroms, one in response to a breakout of haemorrhagic fever in 1356, another when 38 Jews were hanged on the city gates in 1510 for allegedly desecrating the Host. The most significant event, however, was the arrival in 1671 of fifty Jewish families who had been expelled from Vienna. They were welcomed because they brought with them capital and paid for their right of residence. While the French were given tax-free benefits and special assistance in the organization of their visas and arrival in Berlin, and built a great church of thanks to the Germans in 1701 (the Germans built their response, a ‘German’ church, across the famous Gendarmenmarkt in the same period), the Jewish population, one thousand in number by 1701, was forbidden from building a public synagogue, subject to a revocable right of residence, a poll and many other forms of tax, and made collectively responsible for criminal acts. It was only forty years after the arrival of the Vienna Jews, in 1712, that a synagogue was finally built in Heidereuterstrasse. Jews were settled after 1737 in precarious conditions adjacent to the Barn District, where property prices far exceeded the quality of housing. Conditions in Berlin, though terribly unjust, were nonetheless better than elsewhere in Europe. At the turn of the eighteenth century, one can already observe the profoundly multicultural direction of the city and its remarkable ability to absorb peoples, but also the vulnerability of those wh...