![]()

1 Clouds in Myth and Metaphor

‘Tell me, Alvis! You’re the dwarf who knows everything about our fates and fortunes: what is the name for the clouds, that hold the rain, in each and every world?’

‘Men call them Clouds,’ the dwarf replied. ‘The gods say Chance of Showers and the Vanir say Wind Kites. The giants name them Hope of Rain, the elves Weather Might, and in Hel they’re known as Helmets of Secrets.’

Kevin Crossley-Holland, trans., ‘The Lay of Alvis’1

Some of the world’s earliest written documents grapple with the mysteries of clouds and weather. Ancient Egyptian and Babylonian texts, preserved on papyrus or clay tablets, are filled with foreboding over rains and droughts. ‘When a dark halo surrounds the moon, the month will bring rain or gather clouds’, says a 4,000-year-old Chaldean prophecy; ‘When a cloud grows dark in heaven, a wind will blow’, warns another. By the fifth century BC, weather bulletins were being displayed in the public squares of cities across the Mediterranean, filled with astro-meteorological predictions such as ‘September 5: Rising of Arcturus: south wind, rain and thunder’, or ‘September 12: The weather will likely change’. Shang-era Chinese scholars were already keeping detailed weather journals in which sightings of rainbows and haloes were logged, along with rainfall and prevailing winds.2 The harmonious doctrine of yin and yang had been established by the end of the fourth century BC, with yin associated figuratively with clouds and rain (as earthbound elements of the female principle), and yang associated with fire and the heat of the sun (as celestial elements of the balancing male principle). It is the warmth of the (yang) sun that nourishes the (yin) clouds through the mysterious agency of evaporation, while an overabundance of (yin) rain calls up a compensating bolt of (yang) fire to balance things out in the teeming atmosphere.

A few centuries later, Daoist clerics invoked a divine administration known as the Ministry of Thunder, complete with a god of lightning, an earl of wind and the master of rain, whose apprentice, a dissolute minor deity named T’un Y’un (‘The Little Boy of the Clouds’), was given the job of shepherding the rain-bearing clouds. It was he who was responsible for their unpredictable movements, and for the sudden unexpected downpours that soaked the people below. The Eight Immortals of Daoist mythology were usually depicted travelling on small flying clouds, although in one Ming-era text from the fifteenth century the Immortals abandon ‘their usual mode of celestial locomotion – by taking a seat on a cloud’ and demonstrate the scope of their talents by placing objects on the surface of the sea and travelling on them instead.3 Meanwhile, as the meteorologist Ralph Abercromby noted in an 1887 lecture on clouds in folklore, Daoist mythmakers conjured airborne dragons from the turbulence of passing thunderclouds:

‘AD 1608, 4th moon. A gyrating dragon was seen over the decorated summit of a pagoda; all around were clouds and fog, the tail only of the dragon was visible; in the space of eating a meal it went away, leaving the marks of its claws on the pagoda.’

These manifestly refer to the long narrow funnel, or tail-shaped cloud, which constitutes the spout of a tornado or whirlwind.4

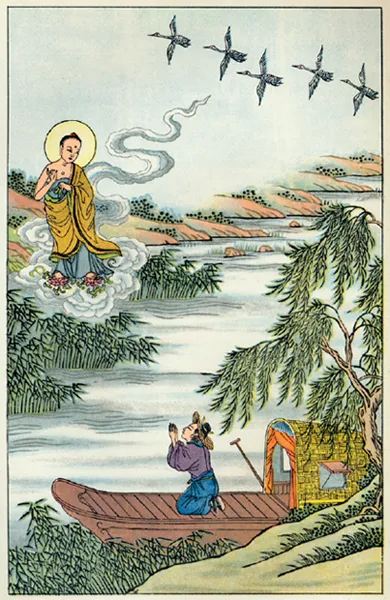

Clouds as a means of divine transportation are also a feature of the Buddhist tradition. A story from the early life of Buddha tells how he summoned a small cloud which obediently ferried him over the Ganges, while the Buddhist cosmology contains a tenfold cloud taxonomy whose stages mirror the tenfold ascent towards enlightenment:

namely: 1) the great bright clouds of perfection; 2) the great bright clouds of mercy and compassion; 3) the great bright clouds of wisdom; 4) the great bright clouds of Prajna; 5) the great bright clouds of Samadhi; 6) the great bright clouds of Srivatsa; 7) the great bright clouds of blissful virtues; 8) the great bright clouds of meritorious virtues; 9) the great bright clouds of refuge; and 10) the great bright clouds of praise.5

The Buddha, needing to cross the Ganges, summons a small cloud which dutifully ferries him over. Anon. Chinese illustrator, 1920s.

Could this have been the origin of the happy phrase ‘to be on cloud nine’, meaning, in this case, to be one step away from enlightenment?

As the boundary between the world above and the world below, clouds have always been the haunt of myths and deities. The ‘cloud damsels’ of Sri Lanka, who emerge from the painted mists of the Sigiriya Rock in a series of well-preserved fifth-century frescoes, are thought to represent the celestial nymphs of Mount Kailash, the revered Tibetan abode of the gods, while in the old Norse pantheon, Odin’s wife, Frigg, sits in the Hall of the Mists, spinning the golden threads to be woven by the winds into morning and evening clouds. These high cirriform clouds were her special preserve, untouched by the hands of other gods, such as the uncouth sons of Bor, who flung Ymir the frost giant’s brains into the air ‘and turned them into every kind of cloud’.6

The ancient Greeks were just as preoccupied with the weather’s moods and appearances, and their philosophers embarked on enquiries into ‘brontology’ (the study of thunder), ‘ceraunics’ (the study of lightning) and ‘nephology’ (the study of clouds). Thales of Miletus (c. 625–545 BC), who is often referred to as Europe’s first scientist, was an impressive meteorological theorist; like the ancient Chinese (whose ideas may well have travelled west along the trade routes), he entertained a semi-mystical reverence for water as the sustainer of life on earth. This reverence, combined with the Homeric belief that the earth was held afloat by a vast aqueous bed, led him to picture a universe based entirely on water, a mobile medium that rose and fell between heaven and earth. Thales’s aqueous ideas attracted many followers, most notably a fellow Milesian, Anaximander (c. 610–547 BC), author of one the world’s first scientific treatises, in which he argued that lightning is caused by friction building up inside turbulent clouds. This was an impressive insight, given that these pre-Socratic philosophers had no instruments with which to test or develop their ideas.

One of the celestial ‘cloud damsels’ of Sri Lanka, depicted emerging from the mist in a well-preserved 5th-century fresco at the Sigiriya complex.

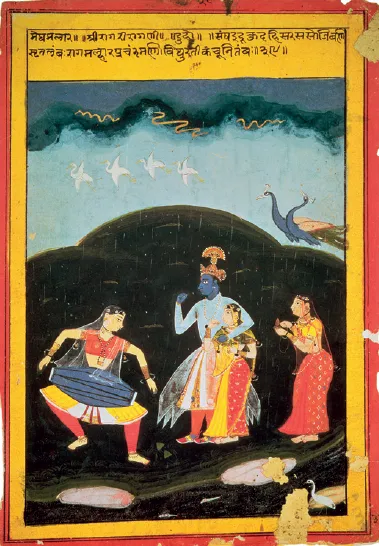

Krishna and Radha in the Rain, 18th century, gouache. Krishna, a much-revered Hindu deity, is described in the Mahabharata as being the colour of a rain-dark cloud. | |

They did, however, have a complex mythology in which clouds were more than just the seats of the gods. Nephele (from nephos: ‘cloud’) was a nymph whom Zeus had shaped from a cloud into the image of his wife, Hera, as a trap to ensnare Ixion, the king of the Lapiths, who had attempted to force himself upon Zeus’ queen. The ruse worked, and Ixion raped the cloud-in-disguise, who subsequently gave birth to the race of centaurs (in this version of the story, all centaurs are the offspring of Ixion and Nephele) in a rain shower upon Mount Pelion. Ixion was aptly punished for his crime by a blast from Zeus’ thunderbolt. In another story, told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Jupiter/Zeus reluctantly arms himself with the thunderbolts that will destroy his lover, Semele, as she beholds the blazing sight of his divine form – the vision that she had tricked the god into promising, but which would prove fatal to her mortal sight. Jupiter weeps as he helplessly ‘gather[s] the foggy clouds around him’, in the words of Ted Hughes’s luminous verse translation:

Now he piled above him the purple

Topheavy thunderheads

Churning with tornadoes

And inescapable bolts of lightning.

Yet he did what he could to insulate

And filter

The nuclear blast

Of his naked impact . . .7

The Norse goddess Frigg spinning cirrus clouds from golden thread in J. C. Dollman’s illustration for H. A. Guerber’s Myths of the Norsemen (1909).

But the doomed Semele was already dead, atomized by Jupiter’s implacable Olympian weather.

Antonio da Correggio, Jupiter and Io, 1531, oil on canvas. In Ovid’s tale from the Metamorphoses, Jupiter assumed the form of a raincloud in which to hide from his wife, Juno.

Clouds come into play once more as Jupiter falls in love with Io, daughter of the king of Argos, disguising himself inside a dark, enveloping rain cloud as a means of evading his jealous wife Juno. The scene, from Ovid, was painted in the 1530s by Antonio da Correggio, as part of the ‘Loves of Jupiter’ series commissioned by the Duke of Mantua, in which Correggio shows the god’s face emerging from a rain-heavy cumulus cloud that clasps the helpless mortal in its damp, misty embrace.

Clouds of prediction

As has already been seen, the idea of weather prognosis is as old as civilization, with clouds – as the only reliably visible portions of the atmosphere – featuring in many of the world’s weather sayings. ‘When the clouds rise in terraces of white, soon will the country of the corn priests be pierced with the arrows of rain’, says a Zuni Indian proverb, while the early Hopi people of Arizona carved rain-cloud petroglyphs onto boulders, perhaps as a means of summoning rain in times of drought.8 A Zuni prayer song recorded in New Mexico in the 1920s pays homage to the U’wanami (water spirits) who are called upon to nourish the land with their rain-bearing clouds:

From wherever you abide permanently

You will make your roads come forth,

Your little wind blown clouds,

Your thin wisps of clouds,

Your great masses of clouds

Replete with living waters,

You will send forth to stay with us.9

In San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, the Cloud Dance is performed every other ...