![]()

1

FLOWING CRYSTALS

what is a liquid crystal?; Friedrich Reinitzer, 1888; Otto Lehmann, 1889; Circus Lehmann; imaging the liquid crystal; naming; physical and chemical life and vitalism; living liquid crystal machines; crystal life; crystal individuals; crystals simplex and complex; blood crystals; liquid crystal nerve casings; life in dust; Haeckel and Lehmann; crystal souls; monism and life; snow souls; strange seas; Urforms and artforms; Michelet and La Mer; jelly and thought; atomic souls; Daniel Sennert’s atoms; abstract gardening; mythic seas; ridicule; crystals, congealments and Marx; crystallized capital; undersea commodity caves; Crystal Palace; commodity crystals; Dresden’s gems; crystals of time; rock crystal; dream crystals

Changeable

Cracked ice in pools of greasy water. Rods with bubbles crowding round drifting spikes. Dense sequins in a pile-up, with black crosses at each centre. Twisting lines of two-tone silk. Crumpled, intricate coils of lines etched in darker hues with reflecting pools between isolated circles afloat in dark space. Pearlescent baubles floating in a shimmery soup. Like Klee. Like Klimt. Like van Gogh. Crinkled and blobby. Spidery legs around dark globules with flecks of glitter dust. Contour marks of maps with dark edging and amoeba-like forms pressing in. They are brightly coloured, should you view them through a polarizing microscope with a hot plate. Light waves are usually unpolarized and so they oscillate or vibrate in many different planes, and in three dimensions. Linear polarized light vibrates in one plane only and this means that liquid crystals may create dazzling, prismatic patterns when viewed between crossed polarized filters. Under polarized light, liquid crystals resemble shattered rainbows, swirling seas of dye, dazzling jewels come to life. These threads, steps, terraces, planes, droplets are as if alive, for they move, under their own power. They meet and coalesce. They copulate, forming new shapes and colours. They seem to be little life forms.

Liquid crystals are animated, a heap of tubular molecules sliding and vibrating and pulling together and away from each other. There are substances that when cold, or starved of energy, are rigid and their particles are arranged in regular patterns. In this state, forces hold the particles together and there is just the smallest amount of jiggle. The substance is a crystal. A crystal consists of layers composed of particles, where each has an allotted place and the molecules in neighbouring layers slot into each other’s gaps, forming a lattice in which the position and direction of each particle is alike. This crystal vibrates, but it is without perceptible movement as such.

If the same substance is heated, the crystal lattice melts. Some of the weak attracting forces are overpowered by thermal motion, while others hold fast. The neighbouring areas of mesh disperse. The molecules scatter in different directions, though each remains on its layer. This means that the substance retains something of its crystalline structure, but at the same time the molecules slide around more or less fluidly. The positional order of the particles only holds in one direction, though orientational order remains. In such a state, the substance possesses, at one and the same time, properties of liquid and of crystal. This is a state of liquid crystallinity, a slimy state of being.

If the heat persists, the molecules loosen all their bonds and the layers begin to wriggle and fragment. There is no positional order: the molecules scatter where they will, though they are still lined up with the same orientation. Each molecule has a proper direction, but no proper place. What was once crystal now flows.

If more heat is introduced, the particles start to bounce around randomly, abandoning any common orientation. Eventually the substance is fully liquid. Molecules distribute themselves in all directions and broken symmetry is introduced, which means that all directions become equivalent. Heated further, it becomes gas, and the molecules crash around randomly at high speed.

Solid, liquid, gas: these are the schoolbook-familiar states of matter. Movement between these states, as one becomes another, is called phase transition. But in between these common phases, forms of liquid crystallinity interpose. Liquid crystallinity is a crossbreed form. The liquid crystal phase exists only for a few minutes on the way from hot to cold or cold to hot. If a substance in the liquid phase is viewed under cross-polarizing light, whereby the polarizers either side of the sample eliminate light with exactly perpendicular polarizations, only blackness is seen. At the moment that liquid crystallinity occurs, colours and shapes flash into view, like a little abstract animated film. This is an animation made by nature itself.

This momentary phase of liquid crystallinity was caught in view for the first time in the 1880s. Liquid crystals were closely observed, if unnamed, in 1888 when Friedrich Reinitzer, an Austrian chemist and botanist in Prague at the Institute of Plant Physiology, experimented with the cholesterol of carrots in the form of cholesteryl benzoate and cholesteryl acetate. Reinitzer was attempting to discover the chemical composition of cholesterol, which had been observed in plants and animals alike, in order to find out if the substance was shared across living forms. He began with crystals and subjected them to heat in order to watch them cool again. As his compounds became colder, he noticed, as others had done before him, a burst of colours just before solidification. But he also noticed, as he heated his sample of cholesteryl benzoate, that it melted in a peculiar way, or, rather, ways. First it melted into a cloudy liquid at 145.5°C. That was to be expected. Compounds melt and solidify at a repeatable and precise temperature. Each solid has a melting point. Each liquid has a freezing point. However, in the case of cholesteryl benzoate, at an even higher temperature, 178.5°C, the cloudy liquid became clear. It melted twice. The same phase transitions were seen as it cooled. Remarkably, too, close to the points of transition between phases, colours flashed up. Reinitzer wrote in March 1888 of how, upon cooling cholesteryl benzoate,

violet and blue colours appear, which rapidly vanish with the sample exhibiting a milk-like turbidity, but still fluid. On further cooling the violet and blue colours reappear, but very soon the sample solidifies forming a white crystalline mass.1

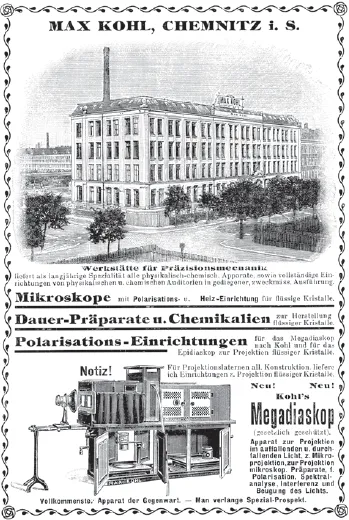

| Advertisement for microscopes, chemical preparations and optical equipment for visualizing and projection, in Otto Lehmann’s Die scheinbar lebenden Kristalle (Apparently Living Crystals, 1907). |

It appeared that this substance could melt into a liquid twice as the temperature increased. Reinitzer also discovered that in its cloudy phase it polarized light in the way that a crystal does: that is, it refracts it twice, in different directions. Reinizter had to conclude that the substance seemed to be crystalline and liquid at once. Reinizter was perplexed and passed his findings to a physicist in Germany, Otto Lehmann. Reinitzer and Lehmann exchanged letters and samples by post.2 They pondered what might be at work as the bright colours briefly flashed up. Lehmann was adept with a microscope and the first task was to examine the substances closely using his home-built one, a crystallization microscope, with polarizers and a moveable object table. Later, he integrated micro-photographic and screening mechanisms into the microscope, making it possible to reproduce and objectify that which the aided eye could perceive.

Lehmann peered at the samples through a polished lump of Iceland spar, which refracts light. Lehmann had stared at crystals for a long time: in his teenage years, his fascination with snowflakes had led to various sketches of their patterns of growth. In addition, he had developed his polarizing microscope to include a hot stage, so that he could make observations under the effects of high temperatures. He described what he did and saw in an article in August 1889:

The substance is heated until a clear melt is formed, and then cooled down slowly. Small blue-white spots appear over all the whole liquid. These grow in number and finally cover the whole space, which now appears as a cloudy-white mass. On further lowering the temperature, plates of common crystals are generated here and there. These quickly grow and eventually consume the cloudy mass; conversely they disperse into it on heating.3

Lehmann confirmed that impossibility appeared possible. He saw

a substance whose crystals could be regarded as in a state of flow from direct observations, yet did not disintegrate and reform, but rather maintained their internal correlation under constant deformation in the same manner as do amorphous and liquid bodies.4

As he looked at the murky fluid, he observed tiny crystals, or crystallites, refracting light. He saw a crystal substance in a state of flow.

If the present interpretation of the observations is to be believed, a unique phenomenon is reported here for the first time. A crystalline and strongly birefringent substance has been observed which possesses such low physical strength that it cannot resist the effect of its own weight. As soon as it is not constrained by a liquid of equal density, it flows like syrup or gum; in this respect it would resemble the swimming oil ball of Plateau, were it to be removed from the influence of gravity.5

Lehmann’s Plateau reference was to the recently deceased scientist from Ghent, Joseph Plateau, who experimented with oil bubbles in water. This was apparently a fascination unleashed by an assistant’s spilling of oil into a mixture of water and alcohol, upon which Plateau observed that the oil formed perfect spheres. If the oil and water have the same density, the bubble freely floats and is not subjected to gravity – its shape being, therefore, the result of molecular forces working in a very thin surface layer.6 When Plateau transferred his experiments with surface tension to soap bubbles, he motivated the study of foam, a physical state that occupies the remaining spaces on a wheel of matter between liquids and gas (mists and liquid foams) and gases and solids (smokes and solid foams).

Lehmann observed of his objects between solids and liquids: ‘The mysterious crystals flow together with the fluid as if they were a part of it, except that they are endowed with a polarization capacity.’7 They flow with it, but they keep themselves aggregated and are able to split light. He poked at his sample with a dissecting needle and observed how along the flow lines crystals and bright spots ran together, forming striations that became broader and broader. Whether the view through the microscope was bright or black depended on the orientation of the sample in respect of the polarizing lenses. He altered the thickness of his samples to obtain different polarization colours.

Lehmann concluded that what he saw was crystalline just as it was liquid, and he named the strange occurrences whose cloudiness stemmed from ‘large star-like radial aggregates of needles’ ‘flowing crystals’, though he did not yet understand them. He also wrote of ‘slimy liquid crystals’, ‘crystalline fluid’ and ‘liquid crystals which form drops’.8 These different forms flowed more or less reluctantly. He wrote about these forms in florid, rhetorical prose. His essay of 30 August 1889 begins with an exclamation and the recognition of paradox:

Flowing crystals! Is that not a contradiction in terms? Our image of a crystal is that of a rigid well-ordered system of molecules. The reader of the title of this article might well pose the following question: ‘How does such a system reach a state of motion, which, were it a fluid, we would recognize as flow?’ For flow involves internal and external states of motion, and indeed the very explanation of flow is usually in terms of repeated translations and rotations of swarms of molecules which are both thermally disordered and in rapid motion.9

‘Flowing crystals’ was the first name of liquid crystals. The crystal had a fluid form. Lehmann seemed to assume that these forms really were liquid and crystalline at once. He had observed their liquid and their crystal behaviours.

In his 1901 lecture Physics and Politics, a reflection on the interconnections of science, technology, power and history, Lehmann emphasized the importance of seeing:

Observation and making discoveries is an art, which must be learned like many others. Anyone who has worked in a physics laboratory knows how difficult it is for the novice to carry out accurate observations. To a certain extent, he has to learn to see first.10

Lehmann added artificial dyes to bring out the patterns in liquid crystals. He sliced through them. He smudged them between glass plates. He applied magnetic fields. All this he captured visually. Lehmann pointed his Zeiss lens at the liquid crystals that he found and witnessed and photographed them, using his specially adapted hot-plate microscope with built-in camera. He built his equipment such that it might make the capturing and visualization of liquid crystals, in their transient and mobile states, possible.11 He had learned to see them and to bring them into visibility. He sought audiences to provide further witness. He worked energetically to present the liquid crystals as extraordinary and himself as their discoverer. The results were shown to audiences in spectacular lectures, in which he and his apparatuses rolled in and out of the performance space of the lecture, as if conjured forth by a magic spell. Seeking to induce wonder in his audience, he projected these curious liquid crystal forms from the microscope plate onto a screen.12 The visuality and animated appearance of his objects formed a key element of his argument: what he showed were particularly vivacious forms. He staged exhibitions, with sequences of images, projections and microscopes. He included microphotographs, drawings and diagrams in all his various publications. Photography was an essential part of the process, for the changeability of the phenomena showed up the limits of unaided human perception.13 Countless images pictured the vivacity of liquid crystals. He also set a research assistant to colouring in some of the reproductions, replicating their rainbow nature. These woodcuts showed circle after circle with crosses and spirals and lines and dots and a range of colours. In 1907, Lehmann participated in the making of a film about liquid crystals, providing samples for the filmmakers, a crystallographer, Ernst Sommerfeldt, and Henry Siedentopf, who in 1903 was the co-inventor, with Richard Zsigmondy, of the ‘ultra-microscope’ for the observation of colloids. Lehmann showed this film, with its wriggling worms of ethyl ester of para-azoxy cinnamic acid, whenever he could.14 In 1921, Lehmann began to make an animated film under the title Liquid Crystals and their Apparent Life. It had four sections and was approved by the Film Censors in Berlin in November 1922. The fi...