![]()

1 CONSUMING WORDS ON THE STREET: 1840–1950

In an article of March 1851 in the periodical Household Words, Charles Dickens described the perfect way to kill a man in Victorian London. He would uncover a secret about his victim and print it on a poster, and would then place a large impression in the hands of an active billsticker. ‘I can scarcely imagine a more terrible revenge. I should haunt him, by this means, night and day.’ In this way, provocative posters would be

glaring down on him from the parapets, and peeping up at him from the cellars. If he took a dead wall in his walk, it would be alive with reproaches. If he sought refuge in an omnibus, the panels thereof would become Belshazzar’s palace to him. If he took [a] boat, in a wild endeavour to escape, he would see the fatal words lurking under the arches of the bridges over the Thames. If he walked the streets with downcast eyes, he would recoil from the very stones of the pavement, made eloquent by lamp-black . . . If he drove or rode, his way would be blocked up by enormous vans, each proclaiming the same words over and over again from its whole extent of surface.

Dickens concluded that his rival would naturally grow thin and pale, reject food and die, his revenge complete.1 He may have exaggerated the pull of the man’s conscience, but his understanding of words in the cityscape was only a slightly inflated one. By the middle of the nineteenth century rapid developments in printing technology dwarfed the gradual transformations that had occurred in the 300 years following Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible. Based on a fortuitous alignment of emerging lithographic print technology, steam-driven presses and a ready availability of cheap ink and paper, the modern poster is a product of the Industrial Revolution. While Plato imagined Athens as a logopolis, a ‘city of words’, he would probably have been astounded at Victorian London. If buildings were not enough, printed advertisements were placed on pavement flagstones, covered commercial carriages and vans that slowly trundled through city streets and even appeared on the sides of boats on the River Thames. At one time, many busy London thoroughfares featured poster-covered cabinets that supported large clock faces. The poster may have made London into a new kind of city of words, but the words were predominantly urging sales. Dickens’s posters announced a world of mass consumption.

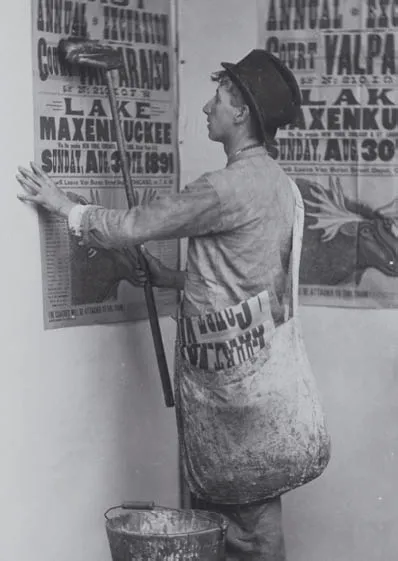

William McConnell, ‘Advertise’, 1863.

The world described by Dickens has disappeared, and another has appeared in its place. And yet we still sense the urgency behind Victorian posters and handbills. Cutting across class lines, these typeset town criers hawked ‘genteel comedies’ and railway timetables; they drummed for local and national politics, lost children or goods, trade-union strikes and rewards for escaped felons. But their primary purpose was to sell. Posters served as classified advertisements, announcing sales of houses, household items and other objects frequently sold in an urban marketplace upon a move, bankruptcy or death. The poster was not just a communicator but also a seller; it was so well established that it was hard to imagine selling goods any other way. ‘How, our commercial forefathers contrived to announce what commodities they had on sale,’ one observer remarked, ‘in this our long famed commercial country, is difficult to discover.’2 Posters opened our horizons, allowed us to look far afield, see new lands and bury ourselves waist deep in the products that they hawked.

Walter Benjamin would later decry how ‘script is pitilessly dragged out into the street by advertisements’.3 Certainly, the brash, bold visual styles representative of the dynamic cities that came of age in nineteenth-century Europe and North America were hard to ignore. Using bombastic, fat faces and other decorative and display type, Victorian handbills carved a new terrain of readership, a space dominated by the strategic use of short declarations, exhortations and aggressive questions intended to catch the eyes of consumers on the move. When Susan Sontag claimed the poster as a capitalist invention, she was not far off;4 with wildly daring abandon, posters materialized an emerging culture of consumption.

The Gallery of the Streets

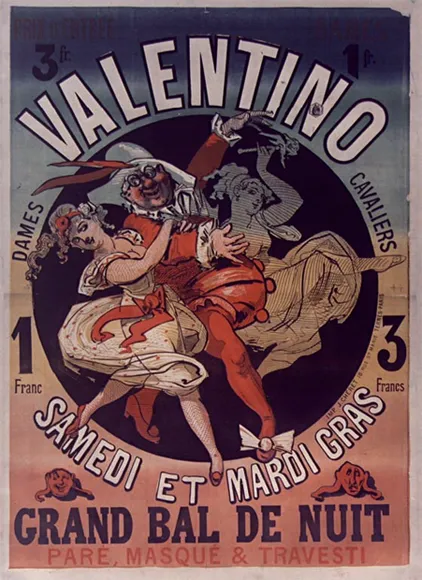

But this consumer landscape was still quite beyond advertising as we understand it today; only when illustrations arrived did posters truly begin to animate streets, alleyways and boulevards while also leaping off fences and into collectors’ portfolios. In 1869 Jules Chéret introduced to France a system of three-colour lithographic printing that assured accurate colour registration, transmuting the poster into artistic gold; a happy confluence of technology, talent and legitimacy made posters into ‘frescos, if not of the poor man, at least of the crowd’.5 Printed in what the poet Camille Lemonnier called ‘electric ink’,6 common street posters were rapidly reconceived as art. Watching with a kind of passive wonder, residents of Paris saw boulevards and alleyways transformed into a ‘gallery of the streets’.

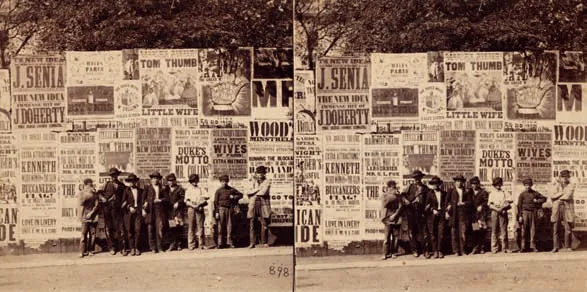

Of course, posted images were not new. Hand-painted signs sometimes included pictures, and from time to time woodcut posters might contain limited illustrations. For many years, Barnum & Bailey, for instance, covered barns and fences alike with crudely worked but bright and vividly illustrated advertising, all carefully timed to precede the circus’s arrival in town. The bootblacks on a stereoscopic card from about 1866 stand before a hoarding in New York’s City Hall Park; they are overwhelmed by P. T. Barnum’s huge advertisements touting Tom Thumb’s wedding, among other posters. But these relatively crude woodcuts were gradually swept aside by the chromolithograph. In France, Chéret’s innovation received a huge boost with the advent of the democratic Third Republic and the passage of the Loi sur la liberté de la presse du 29 juillet 1881, or Press Law of 1881. Posters rapidly came of age. This new legislation not only granted posters protection from censorship, but also from vandalism; furthermore, it inadvertently opened up physical spaces where posters could hang freely and ply their trade. In a sweeping shift, bridges, moving carts and major monuments were all fair game to the city’s legions of billstickers. At first working as freelancers, these unrefined men, often ex-cons or otherwise unemployable, took up the task of papering nineteenth-century cities. Female billstickers were rare, but men quickly took advantage of a new freedom tolerated everywhere except on churches, voting halls and areas designated by local mayors. All else became a backdrop for selling.

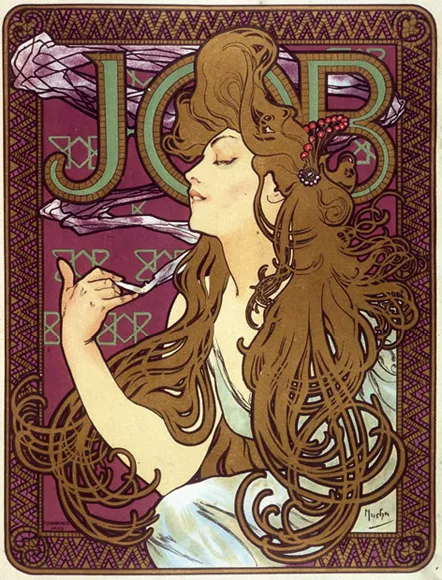

Alphonse Mucha, poster for Job cigarette papers, 1898.

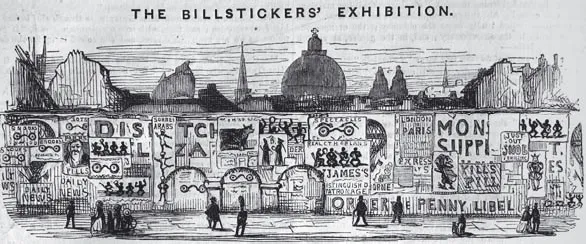

‘The Billstickers’ Exhibition’, cartoon from Punch (1847).

‘The Brigade of Shoe Blacks, City Hall Park’, c. 1866.

Sigmund Krausz, ‘Bill Poster’, 1891. | |

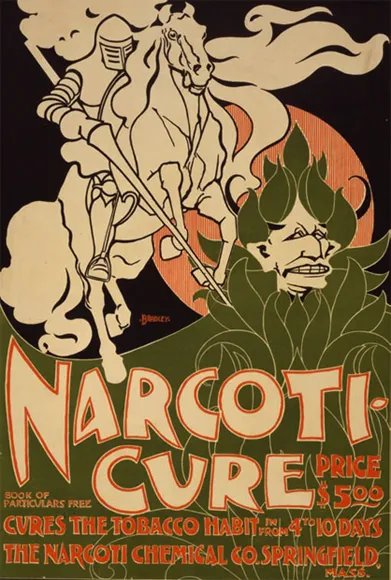

Illustrated posters advertised soap and patent medicine, tickets for travel on steamers and to plays, but they could also hawk new ideas and behaviours. Posters marketing bicycles for women also bespoke freedom to go around the city unencumbered; advertisements for cafés and bars shook off associations of dingy slothfulness and instead suggested an easing of social class lines while cultivating a veneer of cheerful depravity. Alphonse Mucha, for example, began his career promoting theatre productions, but quickly branched out, hawking gas lamps and tyres, chocolate and beer. Advertising was a kind of ether, translating things into products. Mucha’s posters for ‘Job’ cigarette papers promoted paper that could wrap tobacco into cigarettes. Other designers’ work announced dairy milk transmuted by Nestlé into ‘Swiss milk, richest in cream’. Pears Soap was touted as easing’ the White Man’s Burden [by] teaching the virtues of cleanliness’. Nevertheless, before the late 1890s most political posters developed haltingly and often exhibited an almost literary sense of decorum; striking workers, for example, exhorted their fellows in posters covered in huge blocks of texts, their complex arguments meant to be read and digested.7 Occasionally, some posters using wooden type included crudely cut or garishly printed images. But it was only at the very end of the century that politically active artists like Théophile Steinlen and Jules Grandjouan germinated forceful images. Even these, however, were most often used to sell special issues of left-leaning periodicals and books.

In effect, the first picture posters were linked more with capitalism and less frequently with politics; chromolithographs captured buyers’ imagination in ways that were impossible for text-only posters. They tried to foist on the consumer a series of obligations, first insisting that their images be viewed, then pushing the reader to read their text and finally expecting them to buy what was being recommended. They required readers to give themselves up to a fantasia of shaving creams and soaps, theatre productions and circuses. They animated streetscapes, allowing the passer-by to travel into unreality, driven by the imaginary breezes of Turkish cigarettes, cheap chocolate and ‘dirt-killing’ chlorine bleach. Throughout the period, commentators feared that posters appealed to the basest instincts. Many, one British commentator feared, were ‘deplorably bad, from a moral standpoint’.8 Another decried the ‘pandemonium of posters’, while also fretting that ‘much ill’ could ‘be wrought through the eyes’.9 As one worried French politician nervously reflected in 1880, an illustrated poster

William H. Bradley, ‘Narcoti-Cure’, 1895.

George William Joy, The Bayswater Omnibus, 1895, oil on canvas.

Startles not only the mind but the eyes . . . stirring up passions, without reasoning, without discourse . . . [addressing] all ages and both sexes . . . speaking even to the illiterate.10

For good or bad, the French were usually blamed as the first to treat public imagery as potent tools of communication. The illustrated poster came of age in Paris, the art capital of the nineteenth century.11 On the one hand, cheap penny prints had circulated in France for many years; on the other, the elite French Ecole des Beaux-Arts and annual Salon were widely known and imitated across Europe. Unsurprisingly, once censorship laws were lifted, large-scale, easily legible posters with dazzling colours quickly burst on the scene, filling alleyways and omnibus interiors alike. Art, the English aesthete Vyvyan James explained, ‘is laying violent hands on the bill-postering stations’. But, he argued, this transformation of poster hoardings was good, ‘transforming their hideousness into galleries of pictorial beauty’.12

Jules Chéret, poster for the Valentino ball, 1869.

As the lowly handbill was transformed, some commentators argued that the poster pushed to one side ...