![]()

|

ONE

ORIGINS: THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE

|

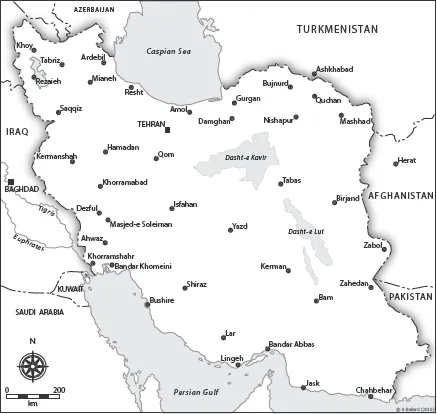

The land into which the ancient Persians moved during the second millennium BC was the belt of alpine mountains which swathe the western and southern fringes of the great plains of Central Asia. These stretch from Europe to East Asia and in most places they consist of two or more enormous ranges separated by high plateaux. In the land occupied by the Persians these ranges are generally aligned in a west-to-east direction. In the north the main mountain range is the Kuhha-ye Alborz – the Alborz – which is part of a sequence of ranges stretching from Anatolia to Afghanistan. The highest mountains of this range lie to the south of the Caspian Sea and the highest peak is Mount Damavand, which reaches a height of 5,601 metres. Damavand is also the highest mountain in the Middle East and the Alborz range constitutes a formidable barrier to movement in the north of the Persian lands.

Lying to the south of this range and separated from it by a series of plateaux is the Kuhha-ye Zagros, the Zagros range. This is a complex series of mountains with a number of peaks reaching over 4,500 metres. The plateaux separating these two alpine ranges are for the most part between 1,000 and 1,500 metres in height. The plateaux are themselves crossed by a number of smaller ranges. The most important of these are the Kuhha-ye Qohrud, which separate the eastern deserts from the rest of the country. On the southwestern flank of the northern Zagros range lies the great fluvial basin of Mesopotamia, drained by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Here the land is far lower than the rest of Iran and consequently the overall conditions are very different.

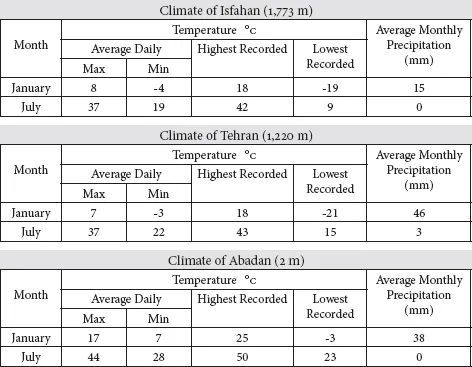

The climate of the country is continental, with considerable annual extremes of temperature and in most places relatively low rainfall. Isfahan, the former capital in the heart of the country lying just to the north of the Zagros range at a height of 1,773 metres, has average temperatures of below zero throughout the winter months, rising to over 30 degrees Celsius during the summer. The annual rainfall is 108 mm and between June and September there is no recorded rainfall. The present capital, Tehran, situated on the southern flanks of the Alborz mountains at a height of 1,220 metres, has similar sub-zero temperatures in the winter with again temperatures rising to over 30 degrees in the summer. The temperature ranges of these two places are very similar but Tehran’s rainfall of 250 mm is far higher than that of Isfahan and there is no month without recorded rainfall.

In general, the continental features of the climate, with extremes of temperature and low average rainfall, are most in evidence on the central plateaux, while the north adjacent to the Caspian Sea and the south constituting the northern shore of the Persian Gulf have heavier rainfall and generally far less extreme temperatures. The centre of the plateau consists of the Dasht-e Kavir (Great Salt Desert) in the north and the Dasht-e Lut (Great Sand Desert) in the east. Surrounded as they are by the northern and southern mountain ranges, these are some of the driest lands in the world, subject to long periods of complete drought and fierce sandstorms. Mesopotamia to the west of the Zagros has many climatic differences and far fewer extremes of temperature.

CLIMATE STATISTICS OF IRAN

Physical map of Iran and the adjacent parts of the Middle East.

The natural vegetation cover of Iran is very varied. While the lower lands around the mountains support forms of steppe grassland, the high mountains themselves support only plants characteristic of alpine environments. Since the centre of the plateau consists mostly of desert and semi-desert, it has very little natural vegetation of any kind. The far north around the southern coast of the Caspian Sea has the heaviest rainfall of all and this has resulted in a Mediterranean-type evergreen forest.

Mount Damavand is the highest mountain in Iran and the whole of the Middle East.

These diverse geomorphological and bio-geographical characteristics determine the suitability of those lands between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf for the support of human societies. This is what the early migrants discovered when they moved southwards during the second millennium BC, and the environmental conditions they encountered strongly influenced the nature of the societies which subsequently evolved in these areas.

The People

The land of Iran has been settled by human beings for many millennia. While primitive pastoralists lived around the mountains and on the more favourable parts of the plateaux, far more advanced societies were developing in the Mesopotamian basin on its western fringes. These were the first civilizations, town-dwelling people who evolved a sophisticated way of life, built fixed settlements, grew crops and developed the use of metals. On the boundary between the two in modern Khuzestan was one of the most advanced of these societies. These were the Elamites, who extended their territory from the plains into the mountains from where they obtained metals and engaged in trade with the east. Their capital was Susa and this was the base from which they were able to gain control over a considerable part of Mesopotamia. They also developed strong trading relations with Sumer and other cities in the region. By the second millennium BC, Babylon had become the dominant city in Mesopotamia and it proceeded to create its own imperial state. Eventually the Elamites were themselves brought into the Mesopotamian political system and incorporated into the Babylonian Empire.

The Alborz mountains form a formidable barrier across northern Iran.

During the second millennium BC, these advanced urban civilizations of Mesopotamia were shaken by the arrival of new groups of people from the centre of Asia. This is known to history as the Völkerwanderung – the movement of peoples or Migration Period – that took place over a number of centuries. This extended migration was probably caused by changing physical and human conditions in their Asian homelands, including deterioration in the climate mixed with population pressures. These people came mainly from the steppes, the temperate grasslands that form a great belt across Eurasia from Eastern Europe to East Asia, and were primarily nomadic pastoralists and animal herders. Changes in climate conditions, which included diminishing rainfall, encouraged them to move away in the hope of finding better land. Such extended nomadic migrations created the conditions for tribal conflicts and eventually for more movements of people in search of new lands.

These migrants to the Middle East were in almost all ways very different from the native inhabitants. They have become generally referred to as Aryans, a word meaning noble birth in Sanskrit. The extensive migrations of the Aryans took them to a variety of places, but they moved in a generally southerly direction. The theory that they were all originally the same people is based on a number of factors, important among which is the discovery by linguists that there were great similarities in the languages spoken by the various branches of peoples who migrated into Europe, India and the Middle East.1 The original homeland of the Aryans who moved to the south is now widely thought to have been the lands west of the Urals and north of the Black Sea, concentrated in present-day Ukraine and adjacent parts of southern Russia.2

Important among those who moved into the Middle East were the peoples who became known to history as the Medes and the Persians. Their most likely routes were either around the west or the east coasts of the Caspian Sea, where passes would have allowed them to penetrate through the mountains. It is known that large numbers first settled in the western parts of modern Iran around Lake Urmia. There they came into contact with the Assyrian Empire, a powerful and highly developed state centred in northern Mesopotamia. This state soon reduced the newcomers to a position of subjection. While the Persians moved away eastwards, the Medes consolidated themselves in the west and by the eighth century BC had established a strong state with its capital at Ecbatana on the edge of the plateau and just north of the Zagros mountains. The Medes then turned on their former overlords and in 612 BC, in alliance with the Babylonians, attacked Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, and within a few years had defeated the Assyrian Empire. Soon after this the Medes also gained ascendancy over the Persians, who were now settled well to the east. Persians had continued to move eastwards, well away from the major Middle Eastern conflict zone, and had settled in the area north of the main range of the Zagros. Known as Pars or Fars, by the early part of the first millennium BC this had become the main area of their settlement and the centre of the state that they proceeded to create. Although they continued to move widely, they came to regard Pars as their homeland and it always retained a very special place in their affections. From this came Persia, the name by which present-day Iran was known to the Europeans in earlier times.

Over time there came to be two centres of power in the lands that were occupied by these Persians. There was Pars itself, and another state called Anshan lying to the west. This division seems to have arisen from the fact that in the middle of the seventh century BC there had been two claimants to the throne and the failure of either to succeed in gaining it resulted in the creation of the two states. When this situation came to an end and the Persian lands were united, the new and more powerful state this created began to exercise a profound influence on the whole of the Middle East.

![]()

| TWO THE ACHAEMENID DYNASTY |

The Achaemenid dynasty was established and given its name by Achaemenes, its eponymous ancestor, around 700 BC. The lands over which he had once ruled soon divided into the two separate kingdoms of Anshan and Parsa. It was not until 559 BC that Cyrus, the son of Cambyses I, ascended the thrones of both Anshan and Parsa and in so doing became the undisputed ruler of the Persian world. He was Cyrus II, the grandson of the first Cyrus, king of Anshan. In acknowledgement of his seminal role in the creation of the first Persian Empire, he has become known to history as Cyrus the Great.

Cyrus set about organizing the new state under his rule with a view to increasing its power and, in this way, gaining greater independence from its overlords, the Medes. It was not long before the Medes became aware of what was taking place under the new Persian king and alarm bells started ringing. They realized that they had to bring their vassal to heel without delay. It had to be made clear to Cyrus who really wielded the power in the Middle East. We learn from a contemporary source, the ancient cuneiform Babylonian Chronicles, that, ‘King Astyages (of Media) called up his troops and marched against Cyrus, King of Anshan, in order to meet him in battle.’

The army of the Medes marched through Anshan and penetrated deep into Pars. There they confronted the forces of Cyrus at Pasargadae in the foothills of the Zagros mountains. They had come a long distance, while the Persians were on home territory. At Pasargadae the Persians conclusively defeated the Mede army and forced it to retreat. Cyrus pursued the Medes and besieged their capital, Ecbatana, forcing the city to surrender.

Seeing the way in which the geopolitical situation in the region was changing fast, Croesus, king of Lydia in western Anatolia, determined to take advantage of the instability. In 547 BC he invaded Media with the intention of replacing Mede domination with his own. Cyrus was certainly not prepared to allow this to happen and he moved westwards from Ecbatana, meeting the Lydian army at Pteria in the heart of Anatolia. Like the Medes before them, the Lydians were defeated and Cyrus continued to move westwards. As he had done with the Mede capital, he besieged Sardis, the Lydian capital, and this city also soon surrendered to the Persians. Following this surrender, the Lydian state collapsed and the whole of Anatolia was soon occupied by the Pers...