![]()

CHAPETER ONE

Tintoretto, Titian, Michelangelo

Tintoretto and Titian

Tintoretto’s artistic identity evolved as a kind of conscious and continual revolution against the model provided by Titian for painting in Venice.1 If the work of many younger painters in the city was specifically indebted to Titian’s towering example, that Tintoretto was, from the very outset of his career, self-consciously defined against it. But the very intensity of Tintoretto’s reaction was, like that of a rebellious son against his father, an admission of Titian’s continued influence in artistic matters. Titian became a point of reference to which the young painter was constantly compelled to return in order to define himself. Tintoretto’s sustained polemic made sense only while the authority of the old painter in Venice lasted. The gradual withdrawal of Titian from the city’s artistic culture after 1560 coincided with the delayed emergence of Tintoretto as a fully independent master whose manner of painting was finally freed of its merely reactive tendencies. But the intensity of this antagonistic relationship left its mark, for in his mature and later work Tintoretto developed (rather than denied) the rebellious pictorial schemas of his youth, arriving at an individualistic manner which had few precursors and even fewer followers.

The reasons for the peculiar intensity of the young Tintoretto’s reaction to Titian are not wholly clear, and certainly cannot be fully explained by any one factor. It would be tempting to follow, in the first place, the reports of Ridolfi and Boschini, who record the ejection of the young painter from Titian’s workshop ‘as soon as possible’. Ridolfi makes Titian’s action a result of his recognition and jealousy of his apprentice’s talent, while Boschini goes one step further, interpreting it as a response to the innate eccentricity of Tintoretto’s designs (‘Titian banished him from his house, having seen him so ardent, bizarre and capricious in the greenness of youth’).2 Both accounts are certainly embroidered to make Tintoretto’s banishment a proof of his genius via the revered opinion of Titian. But they may nonetheless have some basis in historical truth. If Tintoretto did indeed spend a short time in Titian’s workshop, this would have been in the early 1530s. He is first recorded as an independent painter in 1539, and his earliest works cannot be dated much before this. For much of the fourth decade, then, Tintoretto’s activity remains largely unknown. His apprenticeship to another painter is not recorded, a historical lacuna which undoubtedly gave rise to Ridolfi’s notion that he was an auto-didact, but recent historians have rightly doubted this possibility. By May 1539, as we have seen, Tintoretto had almost certainly matriculated from the Arte dei Depentori, a qualification dependent on his successful completion of an apprenticeship with a Venetian master. But no convincing teacher for Tintoretto has been found. The style of the major works from this period – the Conversion of St Paul (illus. 8), the Christ Among the Doctors (illus. 11) and Sacra Conversazione (illus. 13) – certainly bears analogy with those of prominent painters in Venice in the 1530s such as Bonifazio de’ Pitati, Andrea Schiavone and Paris Bordone. But his manner is not closely or consistently tied to any one of these masters.3

If the details of Tintoretto’s apprenticeship remain mysterious, the early paintings illustrated here do have two related qualities in common. They share a marked distance from the favoured pictorial idiom of Titian while at the same time making pointed references to ideas and models derived from central Italian art. To some extent, of course, the self-conscious modernity of these paintings merely reflects the young Tintoretto’s responsiveness to contemporary stylistic fashion. By 1540 the formal values of central Italian Mannerism had spread to Venice, not least through the contemporary working visits to the city by painters such as Francesco Salviati, Giovanni da Udine and Giorgio Vasari. But these recent developments in artistic style might not wholly account for Tintoretto’s immediate independence from Titian. If we allow that Tintoretto was banished in acrimonious circumstances from Titian’s workshop shortly before, then the immediate assertion of difference must have contained a polemical edge.4

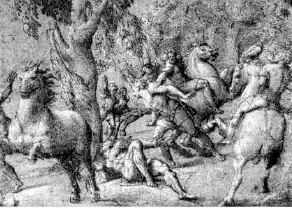

In the Conversion of St Paul (illus. 8) Tintoretto refers directly to Titian’s recently completed battle painting in the Ducal Palace, the Battle of Spoleto (finished in 1538, destr. 1577). But the reference is, at the same time, offered as a kind of corrective revision. Tintoretto’s equestrian conception of the scene owes more to the work of the Michelangelesque painter Pordenone than to Titian. He seems to have known Pordenone’s drawing for a Conversion of St Paul (illus. 9) although his borrowing of the rearing horse at the left might equally be based on a fresco on the facade of the Palazzo d’Anna by the same master (see illus. 30). The key figures of God and Saul owe more, however, to Raphael’s now lost tapestry cartoon which had been present in the Grimani Collection in Venice since 1521. Tintoretto thus thoroughly modified his source with reference to artistic ideas derived from central Italy.5 The reference to Pordenone is, as we shall see, a significant one, given the Friulian’s own overt challenge to Titian’s position at Venice in the 1530s (Pordenone had even offered to paint the Battle of Spoleto, following Titian’s delay). The borrowing from a work in the Grimani Collection, on the other hand, is indicative of one important source for Tintoretto’s burgeoning interest in central Italian art. The young painter undoubtedly knew well the famous collection of antique and Renaissance art housed in the family palace of Giovanni and Vettore Grimani at Santa Maria Formosa. He painted a portrait of Giovanni Grimani and possessed a cast of a Roman bust in the collection, after which he and his pupils made repeated studies. The palazzo, decorated in 1539–41 with all’antica ceilings by Francesco Salviati and Giovanni da Udine, was itself the single most important monument to artistic Romanism (romanitas) in mid-cinquecento Venice, and a centre for the dissemination of central Italian culture in the city. As such, it was a site of especial importance for the young Tintoretto.6

9 Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone, Conversion of St Paul, c. 1532–3, pen and brown ink with brown wash, heightened with white on grey-green paper, 27.2 × 41.1. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. | |

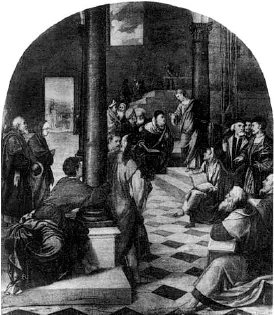

In another large-scale work from this period, Christ Among the Doctors (illus. 11), a breathtaking plunge into pictorial space is necessary in order to arrive at the tiny figure of the young Christ in the background.7 The radicalism of Tintoretto’s formal inversion is evident when one considers that narrative composition in Venice was usually closely tied to the picture plane, the viewer’s eye processing in orderly fashion across the image from left to right (see illus. 23, 24). The whole composition is animated by rapid and exposed brushwork which quickens our apprehension of individual form even while it leaves the picture surface as a kind of scarred battleground. Tintoretto’s bold spatial manipulations undoubtedly owe much to contemporary painting in Florence and Rome, where sophisticated departures from the ‘simple’ centralizing compositions of the preceding High Renaissance period (1480–1520) were already a commonplace. But, as so often in the early career of Tintoretto, influence from abroad was mediated through the practice of local painters. An interest in spatial effects is already very evident in narrative paintings by Bonifazio and Bordone dating from the 1530s, where it is generated by the inclusion of theatrical architectural perspectives. These were typically based on the designs of Sebastiano Serlio, a former pupil of Baldissare Peruzzi in Rome, who had arrived in Venice in 1527. The violently recessional architecture in Tintoretto’s Christ Among the Doctors may not be directly dependent on a Serlio design, but the theatrical qualities of the composition already reflect the new expressive possibilities these had created for narrative painting. In a number of subsequent works by Tintoretto from the 1540s, Serlio’s continuing influence can be traced to specific illustrations in L’architettura (published in six parts between 1537 and 1551) (see illus. 68).8

10 Bonifazio de’ Pitati, Christ Among the Doctors, c. 1536, oil on canvas, 200 × 180. Palazzo Pitti, Florence. | |

Tintoretto’s compositional inversion in the Milan painting may have been directly suggested by Bonifacio’s depiction of the same subject painted around 1536 for a room in the Venetian treasurer’s palace (Palazzo dei Camerlenghi), where the protagonist is likewise removed from the centre foreground into depth (illus. 10). But there is no model here for the massive ancillary figures which dominate the foreground of Tintoretto’s picture. The complex twisting postures of these figures continually return the viewer’s eye back to the picture plane, creating a vibrating tension between surface and depth that was to become a leading characteristic of Tintoretto’s manner. These huge figures increase the drama of Tintoretto’s spatiality, providing a dramatic contrast in scale with the distant figure of Christ. But their movements are essentially arbitrary, the exaggerated torsions and foreshortenings owing more to the painter’s volition than to the dictates of nature. Here again, a distinction is marked from the naturalism of Titian’s preferred mode.

Despite the playfulness of the composition, the Chr...