![]()

1

Independent Landscape

The first independent landscapes in the history of European art were painted by Albrecht Altdorfer. These pictures describe mountain ranges and cliff-faces, skies stacked with clouds, rivers, stream-beds, roads, forts with turrets, church steeples, bridges, and many trees, both deciduous and evergreen. Tiny, anonymous figures appear in some of the landscapes. But most are entirely empty of living creatures, human and animal alike. These pictures tell no stories. They are physically detached from any possible explanatory context – the pages of a book, for example, or a decorative programme. They are complete pictures, finished and framed, which nevertheless make a powerful impression of incompleteness and silence.

These landscapes are small enough to hold in one hand. They were meant for private settings. Extremely few have survived: two were painted not directly on wood panel like ordinary narrative or devotional paintings, but on sheets of parchment glued to panel; three others were painted on paper. Altdorfer also made landscape drawings with pen and ink, and he published a series of nine landscape etchings. Altdorfer signed most of his landscapes with his initials. He dated one of the drawings 1511 and another 1524, and one of the paintings on paper 1522. In Altdorfer’s time, drawings and small paintings were seldom signed or dated. A signed landscape, given its unorthodox content and ambiguous function, is doubly remarkable.

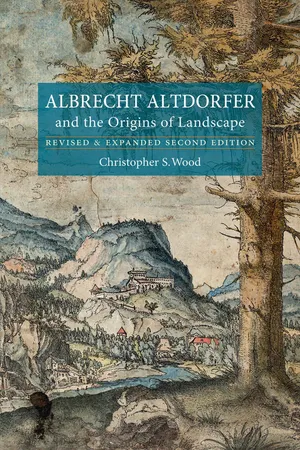

The Landscape with Woodcutter in Berlin, painted with translucent washes and opaque bodycolours on a sheet of paper 20.1 centimetres high and 13.6 wide, opens at ground level on a clearing surrounding an enormous tree (illus. 1). At the foot of this tree sits a figure, legs crossed, holding a knife, with an axe and a jug on the ground beside him. From the trunk of the tree, high above his head, hangs an oversized gabled shrine. Such a shrine might shelter an image of the Crucifixion or the Virgin; in this case we cannot say, for it is turned away from us. The low point of view and vertical format of this picture reveal little about the place. Is this a road that twists around the tree? Are we at the edge of a forest or at the edge of a settlement? The tree poses and gesticulates at the centre of the picture as if it were a human figure, splaying its branches into every corner. And yet it is truncated by the black border at the upper edge of the picture.

1 Albrecht Altdorfer, Landscape with Woodcutter, c. 1522, pen, watercolour and gouache on paper, 20.1 × 13.6. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin.

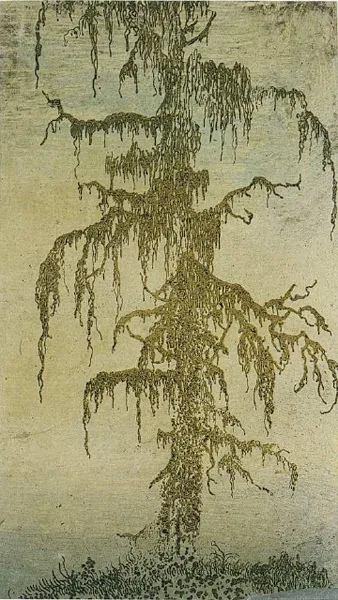

2 Hercules Segers, Mossy Tree, c. 1620-30, etching on coloured paper, 16.9 × 9.8. Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam.

To this iconographic austerity corresponds a great simplicity of means. Many effects are achieved with few tools. The picture is imprecise, shambling, genial, candidly handmade. The branches of the tree sag under shocks of calligraphic foliage, combed out by the pen into dripping filaments. This pen-line emerges from under layers of green or brown wash at the margins of the tree-trunk and the copse at the left, in licks and tight curls, legible traces of the movement of the artist’s hand. Contours do not quite coincide with masses of colour. Behind the tree-trunk, a row of trees was outlined in pen, but never coloured in. The brittle buildings tilt to the right. The picture is touched by a slightly manic spirit of exaggeration, which makes the woodcutter’s passivity and the silence of the place even more uncanny. These are rough-hewn and generous effects. A curtain of blue wash creates a breathy, sticky ether that fades into white near the profile of the mountains. The mountains – blue, like the sky – are overlaid with a ragged net of white streaks. Masses of leafage, by contrast, are made tangible by a speckling of bright green, so unreal that it conspicuously sits on the surface of the picture rather than in it. Paint adheres to paper like a sugary residue. All the picture’s technical devices are disclosed, yet they look unrepeatable.

Such a picture as Altdorfer’s Landscape with Woodcutter – as rich as a painting, as frank and gratuitous as a drawing – is not easily located either within an art-historical genealogy or within a cultural context. No Netherlandish or Italian artist of the early sixteenth century produced anything quite like it. Some German contemporaries and followers of Altdorfer did make independent landscapes. Wolf Huber of Passau, it appears, even established a kind of trade in landscape drawings. Altdorfer published some of his own ideas about landscape in his brittle, spidery etchings, and indeed through these etchings he exerted an impact that can be traced for several generations. But by and large this is not a success story. The independent landscape staked only the feeblest of claims to the surfaces of wood panels, which in southern Germany around 1500 were still largely the territory of Christian iconography. Nothing like Altdorfer’s mute landscape paintings, with their elliptical idioms of foliage and atmosphere, would be seen again until the close of the sixteenth century, in the forest interiors of Flemish painters working in the wake of Pieter Bruegel: Jan Bruegel the elder, Jacques Savery, Lucas van Valckenborch, Gillis van Coninxloo.1

Not until the tree studies of Roelandt Savery, Hendrick Goltzius, and Jacques de Gheyn II did anyone again twist a trunk or attenuate a branch with such single-minded fantasy.2 But the most apt comparisons of all are the moody etchings of Hercules Segers, an eccentric and still dimly perceived giant of early seventeenth-century Dutch landscape, pupil of Coninxloo and powerful inspiration to Rembrandt, working a full hundred years later than Altdorfer. Only a single impression survives of Segers’s Mossy Tree, an etching on coloured paper of a nameless, spineless specimen that might have been plucked from a fantastic landscape, perhaps from one of Altdorfer’s etchings (illus. 2).3 Indeed, the affinity between Segers’s prints and those of Altdorfer’s earliest followers was remarked on as early as 1829 by J.G.A. Frenzel, the director of the print cabinet in Dresden.4

Altdorfer’s independent landscapes, as strange and unprecedented as they were, left no discernible traces in contemporary written culture. They are mentioned in no letter, contract, testament or treatise. The earliest documentary reference to a landscape by Altdorfer dates from 1783; that picture has since disappeared. One of the surviving landscapes can be traced back to a late seventeenth-century collector, but no further. Thus we do not even know who originally owned or looked at these pictures.

What does an empty landscape mean? Christian and profane subjects in late medieval painting were often staged in outdoor settings. Many pictures juxtaposed and compared earthly and heavenly realms, or civilization and wilderness. Many stories about saints revolved around spiritual relationships to animals or to wilderness. German artists, and Altdorfer in particular, addressed these themes also through rejuvenated pagan subjects, such as the satyr, or through autochthonous mythical characters, such as the forest-dwelling Wild Man. Literary humanists – many of whom kept company with artists – debated the historical origins of Germanic culture and its peculiar entanglement with the primeval forest. But none of these themes is simply illustrated by Altdorfer’s landscapes. These pictures lack any argumentative or discursive structure. They make no move to articulate a theme. Instead, they look like the settings for missing stories.

Deprived of ordinary iconographic footholds, one might well wonder whether the early independent landscape is not simply an image of nature. But German pictures in this period, particularly small and portable pictures on paper or panel, had limited tasks: they told stories; they articulated doctrine; they focused and encouraged private devotion. To ask the landscape of the sixteenth century to be a picture ‘about’ nature in general is to impose a weighty burden on it. We would probably not think to do it had not some Romantics elevated the landscape into a paradigm of the modern work of art. Schiller, for example, expected the landscape painting or poem to convert inanimate nature into a symbol of human nature.5 The difficulty of the early landscape is that it looks so much like a work of art.

Both Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer, Altdorfer’s older contemporaries, had something to say about nature. Nature for Dürer meant the physical world. This nature ought to curb the artist’s impulse to invent and embellish, to pursue private tastes and inclinations. ‘I consider nature as master and human fancy [Wahn] as a fallacy’, wrote Dürer.6 His erudite friend Willibald Pirckheimer, in a humanist ‘catechism’ of 1517, an unpublished and only recently discovered manuscript, numbered the ‘striving for true wisdom’ among the highest virtues: ‘Observe and study nature’, he advised; ‘inquire into the hidden and powerful workings of the earth’.7 Cognition of nature, in Pirckheimer’s catechism, became an ethical duty. In his book on human proportions, published posthumously in 1528, Dürer warned that ‘life in nature reveals the truth of these things’. Nature provided examples of beauty and correct proportions, and therefore the controlling principles of art: ‘Therefore observe it diligently, go by it, and do not depart from nature according to your discretion [dein Gutdünken], imagining that you will find better on your own, for you will be led astray. For truly art is embedded in nature, and he who can extract it, has it.’8 For Dürer, the study of nature was a discipline, and nature itself the foundation of an aesthetic of mimesis. ‘The more exactly one equals nature [der Natur gleichmacht],’ he stated in two different treatises, ‘the better the picture looks’.9 But Dürer never suggested that nature should become the basis for an independent landscape painting, and indeed he did not make any such objects. In his drawings he left first-hand accounts of his investigations into the morphologies of animals, plants and minerals. But these were private experiments and memoranda, not public works. His watercolour and silverpoint landscape views registered the impressions of a traveller. Dürer’s eye was too hungry, and often he did not spend enough time on the paper to finish the drawing. Instead, a change of sky or a suddenly perceived riddle of foliage would distract him from the discipline of pictorial organization, and the work would never be concluded. Water-colours like the Chestnut Tree in Milan10 or the Pond in the Woods in London (illus. 74) break off in the middle – appealingly, to our eyes. When Dürer ran out of patience, or light, he simply stopped adding layers of wash. Dürer was charmed by the random datum and the ephemeral impression. His Fir Tree in London, rootless, floats on perfectly blank paper (illus. 3).11 Pedantry would have killed the tree, robbed the boughs of their spring and splay. Instead Dürer wielded the brush with a draughtsman’s agitated hand. He animated the fir with a mass of short, wriggling strokes overlaid on a base of yellow and green washes; the strokes escape around the edges like fingertips. Such a transcription of a particular tree manifests neither the vagaries of personal inclination nor the stable certainties of intelligible nature. Dürer’s watercolour studies, even if completed, were never offered to the world as pictures.

3 Albrecht Dürer, Fir Tree, c. 1495, watercolour and gouache on paper, 29.5 × 19.6. British Museum, London.

Leonardo, whose thinking was more involuted, escaped this impasse. Science or knowledge, for Leonardo, would reveal the principles and dynamic processes of nature – an ideal or ‘divine’ nature – while painting would accurately represent the visible data – the works of nature. But those principles of dynamic or generative creativity uncovered in nature could then serve as a model for the inventive and fictive capac...