![]()

1 The Science of Comets

This is a golden age in comet science. Until recently our study of comets has been almost entirely hands off – photos from Earth or from orbital telescopes – but we are now able to observe and sample up close. Since the first years of the twenty-first century, scientists have directly sampled the tails of comets; sent spacecraft to rendezvous with comets; slammed impactors into comets to study their substance and structure; and on 12 November 2014 even landed a probe on a comet for the first time. Some of what scientists are learning is brand new information, some discoveries have helped to confirm what we learned from afar and some they are still trying to figure out. All of the data tells us that comets are some of the most fascinating objects in the Solar System; but first, let us discuss where comets come from and what they are made of.

When you look at the Solar System you see a lot of rocky planets, plus the asteroids, nestled in close to the Sun; further out the planets, moons and other objects tend to be gas and ice. Saturn’s rings, a number of major moons and most of the bodies beyond Neptune are made of ice – in this case, ice includes not just frozen water, but frozen carbon dioxide, frozen methane and a number of other gases cooled to cryogenic temperatures. The Solar System is, in effect, sorted out by temperature: the Sun boiled off many of these volatile materials from the inner Solar System, leaving behind mostly rock; temperatures in the outer Solar System were lower and the gas and ice remained.

Somewhere between five and six billion years ago, there was no Solar System. In our part of the Milky Way, there was only a cloud of gas and dust spinning slowly in space. Even today our galaxy has thousands of dust and gas clouds lacing its structure; some of these clouds are as old as our galaxy and nearly as old as the universe itself. Left on its own, our gas and dust cloud would have remained quietly occupying its own corner of the galaxy. But it was not left on its own – about five or six billion years ago (give or take a little), a nearby star exploded, and when the shockwave ploughed through space, it compressed some of the gas and dust ever so slightly, creating regions that were fractionally denser than others; the denser areas contained more mass and exerted slightly more gravitational force than their more rarified neighbours. Over time an increasing amount of gas and dust collected in these denser areas, increasing their gravity even more. In a handful of millions of years, the cloud had collapsed, forming a nascent star surrounded by a swarm of planets. Minor planets collided and merged, eventually settling out into the Solar System we see today: a few rocky planets warmed by the Sun, a few chilly gas giants and a host of rubble (the asteroids) in between.

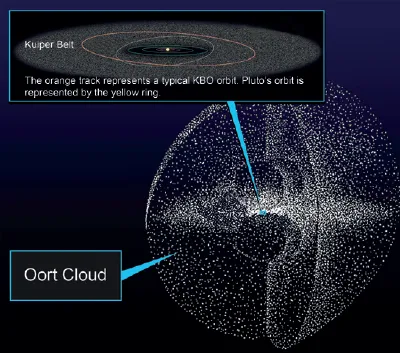

Nothing in the universe seems to stand entirely still, and the solar nebula (as the gas and dust cloud is known) was no exception – it was rotating slowly in space. As it collapsed, it spun up, rotating ever faster the smaller it got to conserve angular momentum (the classic example of this sort of thing is an ice skater who spins faster as she pulls in her arms). But there’s more to it than that – spinning objects experience centrifugal force. So picture a big cloud of gas that is spinning in space: the rotational velocity will be highest in the middle (equivalent to the equator on Earth) and will be lowest at the top and bottom (the ‘poles’). The Earth is solid so this centrifugal force only creates a slight bulge round the equator; a cloud of gas is something else entirely. There comes a point at which the inward pull of gravity is balanced by the outward centrifugal force; when the cloud gets to this point, it will continue to collapse at its poles, but the equator maintains about the same radius. This balance of forces means that the inner part of the cloud becomes a disc. This is why our galaxy is disc-shaped and why all of the major planets in the Solar System are roughly aligned with the Sun’s equator in a plane called the ecliptic. But comets are born far outside where the planets reside – in the frigid outer reaches of the Solar System, the centrifugal force is minuscule so there is no longer a disc; comets are knots of material scattered throughout the sky in a sphere centred on the Sun.1

These knots of material – ‘dirty snowballs’ in the words of the American astronomer Fred Whipple (1906–2004)2 – are generally stuck in the outskirts of the Solar System. Tethered only tenuously by the Sun’s gravity and warmed not at all, these lumps of ice and dust circle the Sun more slowly than any of the closer objects – an object loitering in the outermost Solar System moves at the speed of a brisk walk. Objects this far out are also easily perturbed by passing stars: although most of the bodies in the Solar System had settled out into the ecliptic, repeated tugging by the stars and gravitational scattering by Jupiter and Saturn pulled the furthest ones into more random orbits until they formed a spherical cloud that extended outwards halfway to the nearest stars. Every now and again one of them will be perturbed even more and it will plunge in towards the Sun. As they warm up, the most volatile gases boil off, carrying dust with them and forming spectacular tails. These are the comets and they are among the most ancient objects circling the Sun.

The structure and substance of comets

Comets have a distinct structure: when they are in the outer reaches of the Solar System, there is the comet itself; as it draws closer to the Sun, the outer layers of ice boil off and the comet grows one or more tails along with an envelope of gas that is loosely bound by the comet’s feeble gravity. When we look at a comet in our skies, the tiniest part of what we see is what contains the most material, the nucleus. The outer layers (coma and tails) come and go but the nucleus is the heart of the comet. We can have a comet without the tails, but without the nucleus there is no comet.

| The Oort Cloud, which contains billions or trillions of comets, and dwarfs the roughly 500 million km radius of the inner Solar System. |

As long as the comet is out where it normally resides, far away from the Sun in the Oort Cloud – named for the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, who first proposed its existence – or in the Kuiper Belt near Neptune, comets are nothing more than chunks of ice mixed with dust and rocks. Comets have also been described as piles of rubble – masses of ice and rock, although more ice than rock, clumped together and loosely held in place by the objects’ weak gravity. Add a sprinkling of interplanetary and interstellar dust to the surface, along with the odd cluster of other molecules, and you have Whipple’s dirty snowball. Whether we call them piles of rubble or snowballs is almost immaterial; the important thing to remember is that they are small – the nucleus is usually only about 10 km (6 miles) in diameter – and composed mostly of ice with a smattering of other material, such as dust, rock and some complex molecules. The molecules can include simple gases (such as methane, carbon dioxide and cyanogen), as well as more complicated molecules such as amino acids, the molecular building blocks from which proteins are manufactured by our cells. These molecules – both simple and complex – form in the space between the planets and stars; there are some scientists who believe that these might have helped seed the early Earth with the ingredients from which life eventually formed.3

The Earth is differentiated: there is a core made of iron and nickel, a mantle made of iron-rich minerals and a crust composed of minerals rich in silica. In fact, all of the major bodies in the Solar System are differentiated; minor objects are not. The deciding factors are size and chemical composition. The same supernova whose shock wave initiated the collapse of the solar nebula also produced uranium, thorium and even more exotic radioactive elements; these give off heat when they decay, and whatever object contains them will warm up. The larger an object is, the more radioactivity it will contain and the more heat it will retain – smaller objects generate only traces of heat and that heat radiates rapidly into space.

Size has another effect as well – it affects an object’s shape. Larger objects have higher gravity, and this gravity will pull them into a spherical shape; even the Earth, with all its mountains and deep-sea trenches is (relatively speaking) more spherical than a ball bearing.

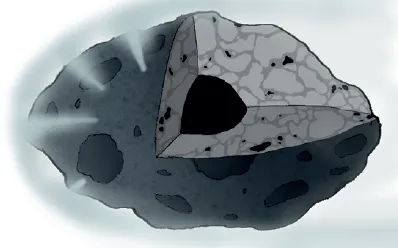

Comets are, by Solar System standards, tiny – the nucleus is usually no more than a few tens of kilometres in diameter. They are too small to be pulled into a spherical shape, too small to generate much in the way of radioactive heat (and far too small to retain it) and too small to become differentiated. What this means is that comets are fairly simple: with no internal structure to speak of, they are merely piles of ice (including frozen gases), dust and rock, hence Whipple’s ‘dirty snowball’. In the outer Solar System, that is about all there is; but as comets approach the Sun, things start to get more interesting.

The structure of a comet. | |

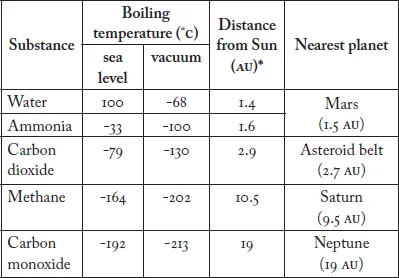

*AU (astronomical unit) is the average distance from Earth to Sun, or about 150 million km.

Every substance has a temperature at which it turns to vapour – its boiling point – and this includes the substances of which comets are made. The table here summarizes the boiling temperatures for a number of these substances as well as the distance from the Sun at which these temperatures will be encountered. This helps to explain why comets lack a tail in the outer Solar System and why their comas and tails form as they approach the Sun. Water, for example, boils at 100°C (212°F) at sea level, but as low as −68°C (−90°F) in the vacuum of space. At atmospheric pressure, ammonia vaporizes at a temperature of about −33°C (−27°F), but in a vacuum that temperature drops to about −100°C. The other volatile substances of which comets are composed each have their own vaporization temperatures: as the comet falls into the inner Solar System, it warms, and the substances boil off into space, carrying with them some of the dust and other molecules that coat the comet’s surface and that are mixed into the ice. As the comet passes the orbit of Neptune, the carbon monoxide begins to boil and, around Saturn, it starts to off-gas methane – but these make up less than 10 per cent of the comet. By the time the comet passes the asteroid belt, it is starting to give off carbon dioxide, and around Mars, both water and ammonia are boiling off into space.

The nucleus of Comet Tempel 1, photographed by the Deep Impact probe prior to impact on 15 September 2005. | |

Significantly, the material does not evaporate uniformly across the surface of the comet, and the gas comes out in jets. Some places, for example, will be shaded, while others are darker-coloured and absorb more solar energy. Some areas might be paved with gravel or dust; some might be covered with materials that have a lower boiling temperature; some locations might simply be stronger or weaker than others. What this means is that some areas are more likely to evaporate first. As the ice melts and boils, it starts to form a crater, and as this crater deepens, it becomes almost like a rocket nozzle, focusing the gas into a narrower jet.4

The gases that boil off the comet form some distinct features. One is the coma, a tenuous envelope of gas and dust that surrounds the comet and that gives it a characteristically fuzzy appearance. In the chilly outer Solar System, the coma might only be the size of the Earth; closer to the Sun it can swell to the size of Jupiter or more. Warmer temperatures mean more out-gassing, and more out-gassing means more gas and dust surrounding the comet – in 2007 Comet Holmes had an outburst of gas and dust that made it temporarily larger than the Sun.

The coma changes size as the comet approaches the Sun, but not in the way that one might expect. As mentioned earlier, the coma will grow in size as the comet warms up, but the solar wind (the flow of gas outwards from the Sun) strengthens as well. By the time the comet reaches the orbit of Mars, the solar wind is starting to strip off the outer layers, and the coma begins to shrink again.

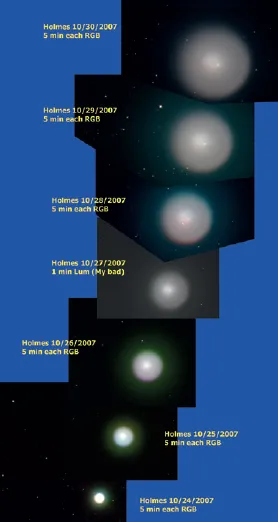

Photo montage of Comet 17P/Holmes following its spectacular outburst on 24 October 2007.

The coma can be impressive, but the tail is what makes comets so spectacular. A comet’s nucleus might be no more than a few tens of kilometres in diameter, and the coma can be more than 1 million km (620,000 miles) across. A comet’s tail can extend over 500 million km, stretching halfway across the sky. But of course there’s more to the comet’s tai...