![]()

1

ART AND ITS DISPLAY IN THE EARLY MODERN ERA

On 26 February 1876, the Treaty of Kanghwa was concluded after much violence and weeks of negotiations. It forced Chosŏn to establish diplomatic relations with Japan and to open its ports for trade.1 It also granted extraterritoriality to the Japanese, who became exempt from import taxes, had the right to use their own currency in Korean ports and, when in Korea, became subject to Japanese law. In the next decade similar ‘unequal’ treaties were signed with Western nations, the first being the U.S.– Korea Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1882.2 Contact with foreign nations initiated heated debates among Chosŏn intellectuals on Western civilization and modernization. On the one side was the conservative majority that advocated the adoption of ‘Western skills’ but urged the upkeep of ‘Eastern morality’ (tongdo sŏgi, literally ‘Eastern way, Western skill’). On the other was a growing number of advocators of modernization and enlightenment (kaehwa). In 1894, Kojong (r. 1863–1907), the last king of the Chosŏn kingdom, oversaw the first major attempts to restructure the government and introduce social change. Commonly referred to as the Kabo Reforms, they signified the formal move towards modernization.3 The drive for change also impacted the cultural scene as new art materials and techniques as well as new understandings of art were introduced. In the 1880s the term misul first came into use in Korea. Meaning fine art, it is the Korean pronunciation of the Japanese term bijutsu that had been coined in 1872 as a translation of the German words Kunstgewerbe and Bildende Kunst.4 Mi (bi in Japanese) means beauty and sul (jutsu in Japanese) means skill. The Japanese origins of misul did not go unnoticed and during the colonial period the term sŏhwa (literally ‘calligraphy and painting’) was sometimes preferred instead.5

The adoption of the word misul precipitated increased exposure to ‘modern art’, with which Western art, particularly oil painting, became synonymous. In contrast to China and Japan, where Western art had been introduced over the course of several centuries, in Korea it entered the peninsula alongside significant political changes that had enormous consequences for the future of the peninsula. Thus the development of Korean modern art cannot be framed purely within a cultural context. Rather, it formed part of the highly politicized tangle of local and international events that unfolded rapidly, within just a couple of decades.6 The appropriation of modern art was further complicated by the fact that Korea’s early encounters with Western art were closely linked to Japan’s presence on the peninsula. In other words, Korea’s engagement with Western art never formed part of a two-way relationship but was entwined in a triangle with Japan as a dominant pole, a point that will be explored in more detail in this and in the following chapter.

Early encounters with Western art

With the termination of the policy of isolation, increasing numbers of Japanese and Westerners made their way to the peninsula for various reasons. Among them were amateur as well as professional artists. Prior to the late nineteenth century, only a small number of men from the upper classes had seen Western forms of art, either in books or in Beijing where Catholic churches were decorated with Western-style murals. The scholar Pak Chi-wŏn (1737–1806) was deeply impressed by his encounter with artworks in these churches when travelling to Beijing in 1780. In his travelogue he noted that the techniques of perspective and shading were beyond description and that it seemed as if the subject matter was alive.

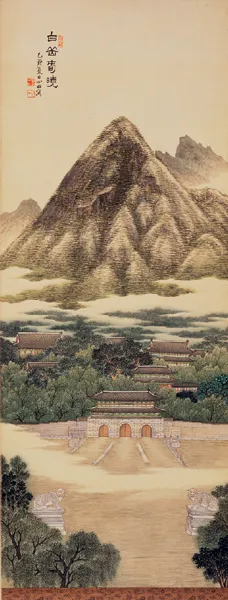

In the nineteenth century some Korean artists began to adopt Western painting techniques like linear perspective and chiaroscuro, suggesting an emerging interest in new types of art.7 Among them were An Chung-sik (1861–1919) and Cho Sŏk-chin (1853–1920), both of whom were highly esteemed painters in the Bureau of Painting (Tohwasŏ) that supplied paintings for the Chosŏn court. In 1881 they had been selected to accompany a diplomatic mission to Tianjin in China where they learnt Western drawing techniques at the Chinese Bureau of Machinery.8 The one-year-long stay offered them the opportunity to experience new forms of art, including Western-style painting, the principles of which they applied in their own works. This is reflected in an album leaf that Cho Sŏk-jin painted a few years after his return to Korea (illus. 1). The painting depicts a meeting of the Bureau of National Defence on 26 July 1894. In the centre fourteen officials sit on benches around a large table strewn with paper and writing materials. Cho’s use of Western-style one-point perspective creates an illusion of space and distance that was not widely employed by Korean painters at this time. Similarly, An Chung-sik’s composition of Kyŏngbok Palace (the main royal palace in Seoul) in spring merges Western-style linear perspective with the aesthetics of traditional East Asian painting (illus. 2). He adopted one-point perspective for the pathways leading up to the main gate of the palace. However, for the background he turned to conventional East Asian ways of expressing spatial distance by placing horizontal bands of clouds between the palace buildings and Paegak mountain (present-day Pugak mountain). Other painters such as Min Yŏng-ik (1869–1941), a nephew of Empress Myŏng-sŏng (1851–95), better known as Queen Min, were instrumental in transmitting the style of the Shanghai School and Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) to Korea.9

With the establishment of trade and diplomatic relations with Japan and Western nations, exposure to new forms of art was no longer channelled exclusively through China. The arrival of Japanese and Western artists facilitated direct access to art that challenged conventional East Asian ways of visual expression through the use of different materials and painting techniques. It seems that there was great interest in Western art, at least among the upper classes, as noted by Arnold Henry Savage-Landor (1865–1924). On meeting the royal family in 1891, he wrote: ‘Both king and princes were very anxious to see what “European” painting was like, as they had never yet seen a picture painted by a European.’10 Savage-Landor was an amateur British explorer who travelled extensively through Africa, Persia, Tibet and China, among other regions. In December 1890 he arrived to Pusan on the southeastern tip of the peninsula and spent the following months journeying throughout the peninsula. Though he was modest about his artistic skill, by the time he arrived in Korea he had painted the portraits of several noteworthy individuals whom he had met on his travels, including the U.S. president Benjamin Harrison and Countess Kuroda, second wife of the Japanese prime minister Kuroda Kiyotaka (in office 1888–9).11 When in Korea, his ability to rapidly sketch local people and scenes roused the curiosity of the royal family, leading to him painting their portraits. His first sitter was Prince Min San[g]-ho, whose life-size portrait in oil wearing court dress received much praise from Landor-Savage’s royal clients.12 Landor-Savage explained the fascination with the artwork as follows:

1 Cho Sŏk-chin, Meeting of the Bureau of National Defence, 1894, ink and colour on paper.

Unaccustomed to the effects of light, shade, and variety of colour in painting, the work merited a great deal of admiration, and many were the visitors who came to inspect it. It was not, they said, at all like a picture, but just like the man himself sitting donned in his white court robes and winged cap.13

King Kojong was so satisfied with the work that he asked Savage-Landor to paint portraits of Prince Min Yŏng-hwan (1861–1905), Commander in Chief of the Korean army, and Prince Min Yŏng-jun (1852–1935), Minister of the Interior (illus. 3).14 The following story testifies to how unfamiliar these distinguished sitters were with Western conventions of perspective and shade. Savage-Landor had prepared a sketch of Min Yŏng-hwan in frontal view and had omitted details of his attire that were out of view. Much to Min’s despair, they included the jade buttons (kwanja) that were sewn onto his headband (manggŏn) and situated on either side behind his ears. As they formed an important part of his court costume, he asked the artist to draw up another sketch in profile, but that also failed to satisfy the sitter. The jade button was now visible but to Min’s disappointment the portrait showed only his left eye (illus. 4).15

2 An Chung-sik, Spring Dawn at Mt Baegak, 1915, ink and light colour on silk.

3 Henry Savage-Landor, Prince Min Yŏng-jun, 1891, sketch.

The first Western professional painter to work for the Chosŏn court was the Dutch Hubert Vos, who arrived in Seoul nine years after Savage-Landor (illus. 5). Born in Maastricht, he studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels and in Paris under Fernand Cormon (1849–1924), an influential French Academic painter. Vos exhibited widely in various European venues, including the Royal Academy in London, where he opened his own studio in 1888 and established himself as a portrait painter. In 1893 he participated in the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago as a commissioner for the Netherlands.16 His encounters with ‘different people of the Globe’ led to an interest in ethnology that motivated him to paint portraits of people from different ethnic backgrounds, beginning with Native Americans.17 Following his marriage to the Hawaiian princess Kaikilani in November 1897, Vos and his bride set out on their honeymoon – a round-the-world trip that would take them to Paris in time for the opening of the 1900 Universal Exposition.18 In spring 1899 Vos travelled from Beijing to Seoul where he met the above-mentioned Min Sang-ho, then mayor of Seoul, who had sat for Savage-Landor a few years earlier.19 Min was aware of Vos’s ...