![]()

1 Angelfish

‘Strange doings go on secretly in this life of her mind.’

Ida Tarbell, The Ways of Woman (1915)

In 1905, when seventy-year-old Mark Twain began to collect a bevy of adolescent girls, whom he called his ‘angelfish’, he defended his predilection by insisting that he longed for grandchildren. His own daughters were grown – his favourite, Susy, was dead by then – and he was lonely. But grandfathers can have grandsons as well as granddaughters, and Twain, creator of one of literature’s most famous adolescents, surely celebrated boys’ cheeky energy. There was more, then, to his strange sorority than an elderly man’s yearning for grandchildren, more even than nostalgia for his daughters’ childhoods. ‘As for me,’ Twain wrote at the age of 73, ‘I collect pets: young girls – girls from ten to sixteen years old; girls who are pretty and sweet and naive and innocent – dear young creatures to whom life is a perfect joy and to whom it has brought no wounds, no bitterness, and few tears.’1

Innocent they were, but not as naive as he seemed to think. Certainly they knew that he was a celebrity: that was how it started, when fifteen-year-old Gertrude Natkin saw him leaving Carnegie Hall on 27 December 1905, after a matinee song recital by the German soprano Madame Johanna Gadski. Twain, after all, was instantly recognizable, even before he decided to wear only white. He noticed her, to be sure, saw that she wanted to speak to him, introduced himself and shook her hand. The next day, she wrote to thank him: ‘I am very glad I can go up and speak to you now . . . as I think we know each other.’ Describing herself as his ‘obedient child’, she ended her note, ‘I am the little girl who loves you.’2 He responded immediately, calling himself Gertrude’s ‘oldest & latest conquest’.3 Their correspondence was playfully flirtatious: he called her his ‘little witch’; she called him ‘darling’.4 He sent her a copy of his favourite book, the writings of ‘a bewitching little scamp’ named Marjorie, who had died just short of her ninth birthday, in Scotland in 1811. ‘I have adored Marjorie for six-and-thirty years,’ he confessed in an essay. The child, who confided startlingly sophisticated remarks about books, history and religion in her journal, seemed to him ‘made out of thunderstorms and sunshine’: ‘how impulsive she was, how sudden, how tempestuous, how tender, how loving, how sweet, how loyal, how rebellious . . . how innocently bad, how natively good,’ he exclaimed.5 ‘May I be your little “Marjorie”?’ Gertrude asked coyly.6 That is how Twain addressed her, in letters filled with what the two called ‘blots’, or kisses – until 1906, when he was taken aback by her turning sixteen. ‘I am almost afraid to send a blot, but I venture it. Bless your heart it comes within an ace of being improper! Now back you go to 14! – then there’s no impropriety.’7 Their correspondence ended, and Twain set his sights on younger girls.

Buoyed by Gertrude’s effusive declarations of love, Twain discovered that it was easy to find other young admirers, primarily from among his fellow passengers on holiday trips to Bermuda. By 1908 he had collected ten schoolgirls, dubbed them his ‘angelfish’, and awarded them membership in his Aquarium Club. In Bermuda, he had special shimmering enamel lapel pins designed for them to wear on their left breast, above the heart. In the spring and summer of 1908, one biographer notes, Twain’s letters to his angelfish comprised more than half of his correspondence: one letter sent or received every day.8 Many contained invitations to the girls to visit him in his palatial house in Redding, Connecticut, which he named Innocence at Home. ‘I have built this house largely, indeed almost chiefly, for the comfort & accommodation of the Aquarium,’ Twain announced in a mock-serious document that he sent to his angelfish, containing the rules and regulations of the club. The lair of the angelfish was his Billiard Room.9

Twain recounted, in an autobiographical entry, how he found his ‘jewels’. One morning in Bermuda, as he walked into the breakfast room,

the first object I saw in that spacious and far-reaching place was a little girl seated solitary at a table for two. I bent down over her and patted her check and said, affectionately and with compassion, ‘Why you dear little rascal – do you have to eat your breakfast all by yourself in this desolate way?’

They arranged to meet after breakfast and, he reported, ‘were close comrades – inseparables in fact – for eight days’.10 A friend later told him that the twelve-year-old girl had asked if he was married, and when learning that he was not – his wife had died – said, ‘If I were his wife I would never leave his side for a moment; I would stay by him and watch him, and take care of him all the time.’ Twain attributed the remark to the girl’s ‘mother instinct’, and willingly submitted, characterizing himself as a ‘degraded and willing slave’.11

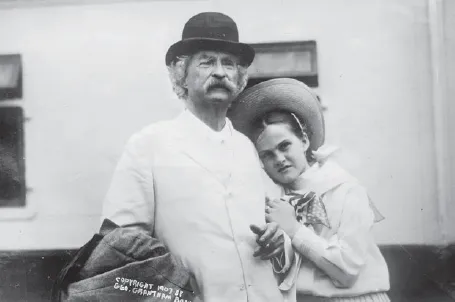

Mark Twain and Dorothy Quick, one of Twain’s Angelfish, 1907.

In 1907, on board a ship taking him to England, where he would receive an honorary degree from Oxford, Twain found the sixteen-year-old Frances Nunnally, with whom, he said, he ‘grew quite confidential’,12 and who became, however briefly, an angelfish; on the return trip, he befriended nine-year-old Dorothy Quick, who, a newspaper reporter noted, ‘guarded him closely during the voyage’, sitting on his lap, with her head leaning against his shoulder.13 He called her ‘mon amie’, another reporter wrote, and stood on deck with his arm ‘thrown paternally around the child’s shoulder’, at one point giving her ‘a fond little hug’.14

Twain’s collection of girls was well known, inspiring some adult women to press for membership. One came for dinner ‘dressed for 12 years, & had pink ribbons at the back of her neck & looked about 14 years old’. Impressed, Twain gave her an angelfish pin. ‘There’s lots of lady-candidates,’ he wrote to a young angelfish, ‘but I guess we won’t let any more in, unless perhaps Billie Burke.’15 The vivacious and youthful comedienne, 23 at the time, was a favourite actress of Twain’s: ‘Billie is as good as she is pretty,’ he remarked to an angelfish after dining with Burke and a few other Broadway performers.16 He had met her after a performance of My Wife, a play whose May-to-December theme fitted his fantasies, and Burke often visited him at his Manhattan townhouse whenever she was working in the northeast.

Innocence at Home, Mark Twain’s residence in Connecticut.

During the years that Twain collected his angelfish, he spurned the companionship of his real daughter, Jean, who had been living in medical institutions where her epilepsy could be monitored. In the summer of 1908 Twain’s secretary and assistant, Isabel Lyon (the Lioness, he called her, and she called him King), arranged for Jean to live in Gloucester, Massachusetts; she stayed there briefly, unhappily, until she left the country with friends. In 1909 Jean returned to Twain’s home, where she drowned in a bathtub, having suffered a seizure.

By the time Jean died, Twain’s blatant cavorting with angelfish had been thwarted by his other daughter, Clara. In the summer of 1908 Clara returned from a European concert tour and was appalled by her father’s new interest. Rechristening the Redding house Stormfield, she put an end to the angelfishes’ visits. The house had lost its innocence, and by that winter Twain began to complain irritably about his declining health and spirits. An odd resurfacing of the angelfish obsession occurred in 1910, just weeks before his death, in letters and notebook entries regarding the fifteen-year-old Helen Allen, a moody young woman who fascinated him. ‘She is bright, smart, alive, energetic, determined, high-tempered, intense,’ he wrote; but she was also disappointing, preferring romance literature to poetry, and responding to Twain’s witticisms and attempts at banter with ‘mute indifference’.17 More disappointing still, she had a boyfriend, and Twain was jealous: he cautioned Helen to preserve her innocence; he wanted the younger man out of the way.

Twain’s obsession with adolescent girls can be explained in part by his exalting of his own teenaged years – years of daring and adventure. His wife, after all, had nicknamed him ‘Youth’, and his most memorable fictional characters, of course, are the adolescent Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. Twain focused not on young boys, though, but sexually innocent girls from ages ten to sixteen, with undeveloped boyish bodies and with whom he carried out titillating flirtations. Photographs of Twain and his angelfish show them standing or sitting close to him, their bodies touching his, with his arms around their shoulders or waists. They might be his daughters; or they might be his lovers. His notes about Helen Allen reveal a yearning to be more than protector, mentor and grandfather. Twain regretted ageing, claiming the vigour of a much younger man. ‘At 2 o’clock in the morning I feel old and sinful,’ he remarked, ‘but at 8 o’clock, when I am shaving I feel young and ready to hunt trouble . . . as though I were not over 25 years old.’18

At the turn of the twentieth century, the image of a man of Twain’s age in the company of an adoring young girl was no anomaly. In literature, such as Jean Webster’s novel Daddy-Long-Legs of 1912, in cartoons and later in movies, the character of a daddy’s girl fulfilled a male fantasy: an older man, usually wealthy, sometimes famous, basked in the attentions of a girl in need of protection and love. Real daughters fed the fantasy. As mothers took on the major role of raising children while their husbands worked in business, daughters learned that fathers were not omnipotent authoritarian figures who must be obeyed, but men who loved to be petted. Daughters read to their fathers, curled up on their laps, nuzzled them. These intimacies stopped short of sex, but fuelled men’s desire for the kind of precocious sexuality that pubescent girls represented. Daddy’s girls were a seductive substitute. Men exerted their power over the girls – they could bestow, or withdraw, attention and gifts; but girls had power, too: to make an older man feel young and virile and valued, and to serve as adornments.

The popular image of the daddy’s girl reflected a prevalent sense of the adolescent female as a sexualized, mysterious being, different from what their mothers had been at the same age, and difficult to control. They were out of their parents’ sight more: in school, on bicycles, shopping in towns. Some talked to friends, privately, on the phone. ‘Strange doings go on secretly in this life of her mind,’ according to writer and reporter Ida Tarbell, whose early career had included teaching. If a girl’s thoughts and desires were revealed, ‘they would throw her elders into fits’.19 Who were these new creatures, parents and educators asked, with urgency and alarm.

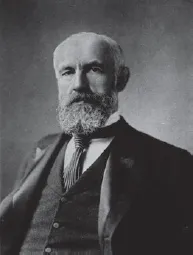

G. Stanley Hall, c. 1910. His two-volume Adolescence (1904) was widely influential.

Their yearning for an explanation was fed by an assortment of men and women boasting particular expertise in observing or studying adolescent girls. None, however, became as famous for his views – detailed, long-winded and insistent – as the educator and psychologist Granville Stanley Hall.

The expert

G. S. Hall was aged fifty in 1894 when he began to work on the two-volume compendium that would appear, ten years later, as Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relation to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education. The book promised to reveal everything that could be known about the physical, mental and emotional development of boys and girls as they passed through puberty. Synthesizing a vast number of sources, he filled more than 1,200 pages with charts, tables and data about the body’s physical transformation, the development of genitals and the trajectory of psychological and intellectual maturity.

He brought in anthropological studies to make his case that humans recapitulated evolution in their development. He portrayed young people as volatile and intense, moody and passionate, as they weathered the storm and stress of growing into adults. Boys culminated in humanity’s highest achievement: the adult male. Girls had different needs, and, Hall asserted, far different potential, intellectually and socially, from boys. His unwieldy, digressive and opinionated tome spoke to an abiding concern among his readers to name and make sense of girls’ experience of adolescence, to formulate educational policy and to guide their daughters. Besides the volumes themselves, which sold well and went into a second printing within months of their publication in March 1904, Hall travelled the country speaking on the topic of which he had made himself an acclaimed expert.

Like his former mentor William James, whose Principles of Psychology ensured his reputation when it was finally published, also after a ten-year g...