![]()

ONE

Nasty, Brutish and Short

‘Nasty, brutish and short’ was how the seventeenth-century authoritarian philosopher Thomas Hobbes described human life in an imagined primitive state of nature, before government came along, with everyone at war with everyone else. And that certainly seems to have been the story for our forerunners, the Neanderthals, who began roaming the earth perhaps 200,000 years ago. An anthropologist who has examined dental records from 130,000 years ago declared of Neanderthals, ‘no-one survived past 30.’ This hardly seems surprising when you discover that Neanderthal remains show that nearly all of them had suffered serious wounds or broken bones, and most had been victims of malnutrition. Neanderthals died out around 40,000 years ago, but some anthropologists believe there was a dramatic increase in human lifespan while our ancestors, Homo sapiens, were living in the Stone Age, about 30,000 years ago, with perhaps two-thirds of those who did not die in childhood surviving past 30, and a few living beyond 50.

The story is all very different in the Book of Genesis. Methuselah, we are told in chapter 5, verse 27, lived for ‘969 years’. We learn little else about him, except that he was the son of Enoch (and the great-great-great-great-great-grandson of Adam) and that he ‘begat Lamech’. Lamech himself did not do badly, chalking up 777 years, but the longest survivor apart from Methuselah was his grandfather, Jared, who lived to 962. We know nothing much about him, either, but the third-oldest person in the Bible is one of the most famous of all Old Testament characters, Noah, whose age when he died, according to Genesis, was 950. He was also the last of the so-called ‘pluricentenarians’. The very good old days ended with the Great Flood that floated his ark. Afterwards, longevity went, along with so much else, to the dogs: Abraham lasted only 175 years and Jacob 147, while Moses shuffled off this mortal coil at just 120. So why were these claims of extraordinary longevity made about the ancient patriarchs? For those who believe in a literal interpretation of the Bible, the answer is straightforward: in those antediluvian times, before God had to punish man’s wickedness so severely, people really did survive to these amazing ages. The more sceptical offer a variety of other explanations. Perhaps an ancient translator confused months and years, or maybe someone simply multiplied the ages by, say, ten. (Both these suggestions generate some odd results, however, such as patriarchs fathering children before they were three years old.) Some thought they had detected an attempt to manipulate ages so that those of notables such as Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph were linked by complex mathematical formulae. Or maybe an ancient writer simply thought that attributing these fabulous ages to the biblical patriarchs would make them appear more important.

Still, even Methuselah’s days seem like the blink of an eye when compared with the Sumerian king En-men-lu-ana, who is alleged to have ruled for 43,200 years. Indeed, stories of extreme longevity are found far and wide in the ancient world. So the Persians had a tyrannical emperor named Zahhak, who is supposed to have reigned for 1,000 years before being overthrown. Three thousand years ago in China, Peng Zu, a highly respected figure in Taoism, was said to have reached the age of 800, while the ancient Greeks had the Cretan seer Epimenides, who, when sent to look after a flock of sheep, nodded off in a cave for 57 years. His age was given variously as 154, 157 and 290. What unites all these claims of extreme longevity is that there is not a shred of evidence to support them.

From ancient Greece, though, we do start to get some clearer statistical evidence about how long individuals lived. A biological anthropologist who examined nearly 150 skeletons from Athens and Corinth concluded that the men survived to an average age of 45, and the women to 36. Until modern times, average life expectancy was dragged down by high infant mortality, and there are clear indications that some ancient Greeks did reach a ripe old age. Men were required to do military service until they were 60, while you had to have passed that age to be eligible for the senate in Sparta. We also become confident enough about the dates of birth and death of some notable people to say Socrates lived to 70 (and even then it took a dose of hemlock to get rid of him). His great pupil, Plato, survived until 80, while the famous playwright Sophocles reached 90, and was still creating new dramas right up until the end. The endocrinologist Professor Menelaos Batrinos has suggested that there are 83 Greek ‘men of renown’ of the fourth and fifth centuries BC about whose life spans we can be certain. Batrinos calculated their average age as about 70. This is strikingly similar to the life span the Bible allocates to humans in Psalm 90: ‘The days of our years are threescore years and ten,’ unless ‘by reason of strength they be fourscore. Plainly, Batrinos’s group is not representative of the ancient Greek population as a whole, and might well be expected to live longer. (Better-off people always tend to survive longer. An American study in the 1960s suggested that those listed in Who’s Who generally had longer lives than the rest of us.) Professor Batrinos notes the factors that would have helped these early great and good: a mild climate, good sanitation and plenty of slaves to do the heavy lifting. They also had the beginnings of the Mediterranean diet – regarded today as among the most healthy in the world. Some of its modern ingredients, such as oranges, lemons and tomatoes, were not grown in Greece at that time, but other fruits and vegetables featured prominently alongside fish, olive oil, mushrooms, onions, garlic and lentils. Ancient physicians advised eating meat and sweet things only in moderation, while recommending tropical spices like pepper, ginger and cinnamon to those who could afford them. Hippocrates counselled, ‘Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,’ but Professor Batrinos considers that the most important factor in ancient Greek longevity may have been the ‘animated social life in which the aged actively participated’ and the ‘great respect’ shown to them. Whatever the exact formula, it seems to have worked. The historian of medicine Mirko Grmek said that in ancient Greece, ‘average lifespan reached heights that were not attained again until the twentieth century.’

Methuselah stained-glass window, Canterbury Cathedral.

Sixteenth-century depiction of the tyrant Tiran Zahhak imprisoned in a cave.

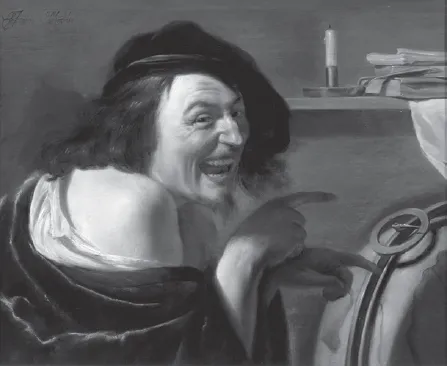

So could the ancient Greeks provide plausible candidates for the title of first known centenarian? An expert on British centenarians, Roger Thatcher, who was Registrar General for England and Wales from 1978 to 1986, calculated it was ‘unlikely’ that anyone reached 100 ‘before about 1700’. But the American demographer John Wilmoth reckons that from around 2500 BC, the world’s population was big enough for the occasional person to make the century, under the law of averages – the idea being that the more humans there are, the greater the chance that the odd one will evade the thousand natural shocks of life to attain the magic mark. And an American actuary named Kenneth Faig, who made a study of longevity in ancient times, gives cautious credence to claims that a philosopher called Gorgias may have been a centenarian. He seems to have been born around 485 BC in Sicily, to have gone to Athens in his fifties as an ambassador, and to have died around 380 BC. Faig says the idea that Gorgias reached 100 should not be ‘rejected outright as implausible’. Around the same time, according to a number of ancient authorities, another philosopher, Democritus of Abdera, may have made it to 109. Democritus was one of the first people to advance the theory that the world is built of atoms. He was known as the ‘laughing philosopher’ and was a great advocate of ‘cheerfulness’, achieved when ‘the soul lives peacefully and tranquilly, undisturbed by fear or superstition or any other feeling’. Sceptical about religion, he thought that people believed in the gods in order to find a way of explaining extraordinary natural phenomena such as thunderstorms and earthquakes.

It seems that when Rome took over from Greece as the centre of Western civilization, life expectancy did not improve. An analysis of inscriptions on tombstones in parts of the Roman Empire revealed that men on average lived to about 45, and women only 30 – but these figures are almost certainly optimistic, since poorer people, who would tend to die younger, would not have been able to afford tombstones. A pioneer of population dynamics named E. S. Deevey gave a lower estimate, of 35, for people in ancient Greece, declining to 32 in classical Rome, but evidence is so scarce that these figures remain highly speculative. Rather than trying to come up with an average age for the whole population, a British neurophysiologist, J. D. Montagu, took a similar approach to Professor Batrinos, considering only Greek and Roman men about whose dates we can be certain. Excluding those who met a violent end, he was left with just 70 individuals, plus another 228 for whom he had reasonable approximate dates. Readily acknowledging that his subjects would have an average life span higher than that of the population as a whole, because they were more prosperous and also excluded those who died in childhood, Montagu concluded that men born before 100 BC survived for a strikingly high average span of 72 years. Intriguingly, though, for those born after that date, the figure falls dramatically, to around 62. Montagu thought this might be because the Romans used lead pipes for drinking water. He also compared his ancient life expectancy figures to those of eminent men who died between 1850 and 1899, and between 1900 and 1949, which averaged out at 71.5 and 71 years, respectively. It was only in the 40 years after 1950 that he detected a significant move up, to 78. Echoing Grmek’s comments, Montagu concluded that it was only since the Second World War ‘that advances in medicine have allowed us to outlive those ancients of the BC era who managed to survive the early perils’.

Johannes Moreelse, Democritus, 1630.

Even though life expectancy seems to have slipped backwards during the Roman era, centenarian candidates continued to appear, such as St Anthony of Egypt, who endured the famous temptations. Considered the father of monasticism, Anthony, during a nineteen-year retreat to a mountain, had to keep fighting off the Devil, who might appear as a monk, a soldier, a wild beast or a seductive woman. Sometimes the Satanic visions beat him to within an inch of his life, but still he was supposed to have lived to 105.

The fall of the Roman Empire was followed by the Dark Ages, and exact information about dates of birth and death generally got lost in the pervading gloom, but as the Renaissance approached things once again become a little clearer. Research on the records of aristocratic families in England in the thirteenth century suggests that men who managed to survive until the age of 21, provided they could then avoid death from violence or accidents, might expect to live on average for another 43 years, a figure that was virtually unchanged in 1745. There were one or two ups and downs on the way, with the figure falling to just 24 in the fourteenth century, when so many died from the Black Death, and reaching its highest at just over 50 between 1500 and 1550. Because this sample group is so small, it would be wrong to read too much into these fluctuations, but they do suggest that even for the privileged few there was not much significant improvement in adult life expectancy from 1200 to 1745.

At all times, overall life expectancy was dragged down by infant mortality, with around one child in ten dying at birth or within its first year, and at least one in four perishing before they reached ten. Children were carried off by a variety of diseases – apart from plague under its various names, there was dysentery, smallpox, measles, typhus and so on. And there were other, more prosaic causes: infections from unsterilized instruments used to cut the umbilical cord, parasitic worms, diarrhoea, gangrene as babies cut their teeth. There were accidents, such as drowning in streams or ponds or even in washing tubs. Lack of sanitation meant that human waste was usually dumped close to the home, spreading disease, while thatched roofs provided a habitat for insects and rodents, and the bacteria they carried. Two Cambridge historians of population, E. A Wrigley and R. S. Schofield, reckoned that life expectancy at birth in England was just over 33 in 1541, fluctuating in the thirties until 1841 when it moved to just above 40.

Still, in spite of the lack of any significant increase in general life expectancy, could medieval and early modern times have provided us with an exceptional person who made it to 100? How about Thomas Parr? A humble farmworker from Shropshire, he lies in Westminster Abbey among the kings, queens, poets, composers, statesmen and generals. His claim to fame is stated on the inscription over his grave, which says he lived during the reigns of ten monarchs. Born in 1483, while the Wars of the Roses were still raging, Parr was said to have made it right through the Tudor dynasty – Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. Then he outlasted the first Stuart king, James I, before finally shuffling off this mortal coil during the reign of James’s successor, Charles I, in 1635. When he learned of Parr’s prodigious age, Charles had the old man brought up to London in a specially built litter, and crowds flocked to see him. He became a national celebrity, as ‘the old, old, very old Thomas Parr’, and was painted by Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, while to this day his likeness adorns bottles of Old Parr whisky. A diet of green cheese, onions, coarse bread and mild ale, or, on special occasions, cider, was his recipe for long life, along with keeping ‘your head cool by temperance and your feet warm by exercise. Rise early, go soon to bed’ and ‘keep your eyes open and your mouth shut’. But the change of air from the purity of the countryside to the putrefaction of the capital did not agree with him, and caused his death after just a few weeks. Or at least that was the view of the great physician Sir William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of the blood, and who carried out a post-mortem at the King’s instruction. Harvey pronounced Parr’s organs to be in exceptionally fine fettle, especially the genitals, which led the doctor to believe the story that the old man and his second wife, whom he married at 122, had intercourse ‘exactly’ as other couples do. He also noted that Parr had had to do penance for adultery and fathering an illegitimate child after his 100th birthday. The old man further proved his fitness by threshing corn at the age of 130. A poetic description of him noted, ‘From head to heel his body had all over/A quick-set thick-set natural hairy cover.’ It is a wonderful story, but nowadays nobody much believes that Parr lived to 152. One possible explanation for how the story gained credence is that his birth date got mixed up with his grandfather’s.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst, The Temptation of St Anthony, c. 1543–50.

William Harvey dissecting the body of Thomas Parr, c. 1900, painting.

Parr’s claimed feat of longevity is not unique. About the same time, in Ireland, the Countess of Desmond was said to have lived to 140, while an 1833 guide to Richmond in North Yorkshire – ‘celebrated’, we are told, ‘for the longevity of its inhabitants’ – recounts the story of Henry Jenkins, who was ‘about’ 169 when he died in 1670. And a churchyard at Brislington in Bristol holds a tombstone with the inscription ‘1542. Thomas Newman. Aged 153. The stone was new faced in the year 1771 to perpetuate the great age of the deceased.’ Bizarrely, a church at Bridlington in East Yorkshire has a board carrying a virtually identical inscription. None of these claims, though, meets the standards of proof required by modern students of the oldest old. (Nor, of course, do the centenarian candidates from ancient Greece and Rome.) So who was the first person we can be sure reached the age of 100? One contender who attracted a lot of support was a Norwegian peasant, Eilif Philipsen, from a fairly prosperous rural area near Bergen. Parish records say he was christened at Kinsarvik church along with his twin sister on 21 July 1682. In 1701, in the first Norwegian census, he is recorded as being eighteen years old. As he approached 40, in 1721, he got married to a 22-year-old. In 1727 he inherited a farm which, 26 years later, he handed on to the husband of his adopted daughter. His death is recorded at Kinsarvik on 20 June 1785, sho...