![]()

PART ONE

A Common Culture

On 14 February 2008, as the contest to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee heated up into the desperate struggle for delegates from Texas and Ohio, Hillary Clinton sent a special valentine to her opponent. Sensing that Barack Obama’s gift for speechmaking was leaving her policy wonkery far behind, she warned workers at the General Motors plant in Lordstown, Ohio, that ‘Speeches don’t put food on the table. Speeches don’t fill up your tank, or fill your prescription, or do anything about that stack of bills that keeps you up at night.’ She continued: ‘Some people may think words are change. You and I know better. Words are cheap.’1

Obama’s answer came swift and certain:

Don’t tell me words don’t matter! ‘I have a dream.’ Just words. ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’ Just words. ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself.’ Just words? Just speeches?

‘Speeches don’t solve all problems’, he admitted, ‘but what is also true is that if we cannot inspire the country to believe again, then it doesn’t matter how many policies and plans we have.’2

Though effective as a quick-fire put-down, this riposte also reached well beyond the local political contest. Obama was alluding to words that really did change American history, Great American Speeches uttered by men like Franklin Delano Roosevelt, John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, a rhetorical tradition of public speaking and writing that runs back through the Declaration of Independence to the first days of settlement in the New World.

More to the point, Obama’s allusions to this long tradition were picked up and understood by a mass audience. This is highly significant, because it challenges the recurrent lament of American writers and intellectuals, from Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James and T. S. Eliot down to the educational theorist E. D. Hirsch, that Americans lack the historical awareness to place the flux of everyday events into the context of a shared culture.

And while it’s true that only a minority of Americans would recognize a quote from Shakespeare or Wordsworth, or even Herman Melville, Mark Twain or Philip Roth, the highly diverse population really does share a culture – not in great literature, or in cathedrals, country houses and traditional social practices, but in public speeches about the values that bind the country together. The Great American Speech is the national culture.

The King’s Speech

Speeches work differently in British culture, where they are seldom delivered to large crowds in the open air. At times the means of their delivery have taken up as much attention as their content. It never occurred to George V to address the empire until the BBC suggested it. As the likelihood grew that his second son would succeed him, so did the panic about Bertie’s stammer. The popular and much awarded film The King’s Speech (dir. Tom Hooper, 2010) is about how he overcame this handicap to grow into his public role as George VI.

The medium is so important because, though British history can claim a share of great election addresses to large crowds, most of the country’s best remembered speeches have occurred indoors, in places to which few, if any, members of the public were allowed access: Lord Mayors’ banquets, party conferences – above all, parliament.

In the nineteenth century the momentous words were conveyed to the public through verbatim newspaper reports, often with helpful guides to the audience’s response: ‘(applause)’, ‘(hearty laughter)’. Most of Churchill’s great wartime speeches were first delivered in the House of Commons; the people got to know them only through the newspapers or when he re-read them on the BBC. More recently television has relayed the big set speeches given at party gatherings, like Margaret Thatcher’s ‘You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning’ (Brighton, 1980) and Neil Kinnock’s attack on Derek Hatton and his Liverpool councillors of the Militant Tendency, ‘the grotesque chaos of a Labour council – a Labour council – hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers’ (Bournemouth, 1985).

Memory and Rhetoric

Sound bites like these are how the British remember speeches – not always fondly. Others include Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of the technological revolution’ (Scarborough, 1963) and Enoch Powell’s ‘the Tiber foaming with much blood’ (West Midlands Area Conservative Political Centre, 1968). But how many can now remember the rest of these speeches, or even their contexts? For that matter who can recall the particular policy on which Mrs Thatcher was refusing to make a U-turn?

In Britain – England in particular – rhetoric and stage-managing are considered suspect. Kinnock was called a ‘Welsh windbag’. Great attention has been paid to how Margaret Thatcher trained her voice to sound at a lower register to give it more authority. Even Churchill came in for criticism from his contemporaries. After the Conservative Party elected him party leader in 1940, one Tory MP commented that he was ‘a word-spinner, a second-rate rhetorician’. His most famous speech, the one on 19 June 1940 that ended ‘People will say, “This was their finest hour”’, was thought to be an indifferent performance in the House of Commons, and when he repeated it that night on the BBC, Cecil King, owner of the Daily Mirror, thought he must be either ill or drunk.

Reviewing a recent book on Churchill’s speeches (Richard Toye’s The Roar of the Lion),3 the historian David Reynolds points out that the great man’s rhetoric was often received with ‘an undercurrent of criticism about his ego, showmanship and propensity to talk – even after his biggest rhetorical hits’. The people trusted Churchill when he told them the truth, Reynolds writes, even if the news was bad, not when he tried to gloss over bad things, like the German warships’ escape from Brest up the English Channel in February 1942.4

Americans, on the other hand, accept the rhetoric of public speaking as part of the form. And they often remember great speeches as a whole rather than in sound bites, because they have had to memorize them at school as a patriotic lesson in American national identity.

Topics

In their long history of parliamentary debate the British have encompassed a wide variety of topics. Some of their best remembered speeches have focused on constitutional issues: Charles I on trial for treason in 1649, claiming that a king ‘cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth’; Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1872) on the role of the monarch and the House of Lords; Labour Party leader Michael Foot opposing piecemeal reform of the House of Lords in 1969. Others have argued for reform, from John Wilkes pleading for a wider franchise to include the new industrial towns in 1776 and William Wilberforce proposing the abolition of the slave trade in 1789, to Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in Cape Town recognizing that a ‘wind of change is blowing through this continent’. Vows to defend the realm, too, have stirred the emotions, from Elizabeth I’s at Tilbury in 1588 to confront the Spanish Armada with ‘the heart and Stomach of a King’, to Churchill’s that ‘we shall fight them on the beaches, we shall fight them on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills, we shall never surrender’.

By contrast the canonical American speeches are about America itself – particularly on how it might be better than it is. And here is the unexpected thing, when you consider that the overriding American ideology is supposed to be all about free enterprise and every man for himself: in the Great American Speech ‘better’ has meant more communitarian, more sharing, more tolerant, not more competitive, richer or more prosperous. Gordon Gekko’s ‘Greed is Good’ speech in Wall Street (dir. Oliver Stone, 1987) to the shareholders of Teldar Paper shocks and amuses the film audience by how it inverts the usual pieties.

Monumental Occasions

Recent research has shown that Great American Speeches, like elegies and inauguration addresses, often fall far short of their intended effect, whether on Congress or the people. Yet they are revered as national monuments – indeed they often become physically part of national monuments, like the excerpts from Franklin Roosevelt’s 1932 acceptance speech promising ‘a new deal for the American people’ in the Roosevelt Memorial, and the Gettysburg Address on the wall behind the big statue in the Lincoln Memorial, itself the site of Martin Luther King Jr’s ‘I have a dream’, delivered to the vast crowd in the mall at the rally for jobs and freedom in 1963.

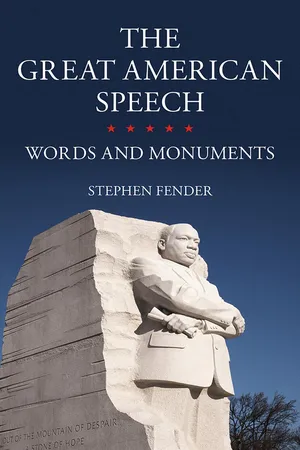

By 2011 King had his own monument, of course, on the southwest corner of the Tidal Basin of the National Mall, near the Roosevelt Memorial, on a sightline between the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials. The great man stands 30 ft high, with his arms folded, emerging in high relief from a rough-hewn granite block. Behind him are two further granite forms, through which the visitor has to pass to get to the figure of King himself. The concept is based on a phrase in his ‘I have a dream speech’ given before the 1963 march on Washington: ‘Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope.’ A long inscription includes fourteen excerpts from King’s sermons and other speeches.

The British don’t do this with their memorials, though they have put a poem – Wordsworth’s ‘Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802’ – on the entrance to the London Eye. The contrast is revealing: instead of being directed didactically to the country’s loftier ideals, the visitor is invited to consider this new view of London in the historical context of an earlier perspective.

Competing Ideologies

This is what makes the moral orientation of the Great American Speech so unexpected: that it runs directly counter to the ‘American Dream’, that promise held out to the world’s poor and downtrodden that if they were willing to risk the disruptive move to America, work hard when they got there, save their money and put off satisfying their immediate whims, they could become as rich and successful in the New World as their former masters in the Old.

Over time this promise hardened into a set of values to be prized above all other human qualities. The virtues of self-reliance, individual risk, private enterprise, energized by relative freedom from government control, grew into the chief constituents of American national self-identity. This is what historians and populists alike have called the American Dream.

Yet fewer have noticed that all this time Americans have also identified in themselves another, quite opposite, set of ideals, going just as far back into the country’s past as the dream of personal success. According to this tradition, the principles distinguishing the nation from the rest of the world are community and equality, in spite of social and economic status.

More often spoken than written – that is, personally presented live and tested by the responses of a live audience – this opposing claim on American identity has always held mass appeal. In popular culture, from sermons and speeches (whether for presidential inaugurations, or just to celebrate the nation), right down to present-day films, the Great American Speech has functioned as a correcting focus on communal themes and values.

![]()

1

Immigrants and the American Dream

EARLY EXPLORERS and settlers carried opposing ideals to America. Puritans like Robert Cushman and John Winthrop wanted a sharing society, while adventurers like Captain John Smith thought the settler could be set free from Old World social and economic constraints in order to better himself in the New.

Though the Puritans may have considered Smith’s ambition to be the selfish default position of fallen mankind, it was a competing ideology, in its way as radical as the proposition that America should form itself into a communitarian polity. In fact, the impulse for self-improvement had been there from the beginning: a fully articulated programme of its own, part of the argument for ‘western planting’, as they called the settlement of the Americas, and it was tightly woven into the proposal for American settlement from the beginning.

This argument was advanced, not in stirring speeches but in vigorous prose, both visionary and concrete in its command of the English vernacular. Smith was the resourceful, energetic and courageous leader of the Virginia Colony at Jamestown, from 1608 the first permanent English settlement in North America. While exploring the Chickahominy River and trading with the natives for food, as he was later to tell the story in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624), Smith was captured, sentenced to death and saved only at the last minute by Pocahontas, daughter of the Algonquin Chief, Powhatan. Smith’s negotiations with the natives and Pocahontas’s supposed love for him, with its figurative marriage of Native and European, conquered and conqueror, nature and culture, became one of the founding myths of America.

After being wounded by a gunpowder explosion, Smith sailed home for England in October 1609. It was to be some time before he was active again in trans atlantic affairs, but in 1614 he sailed to what he was the first to name New England, mapping the coastline and exploring the interior for marketable raw materials.

Like Richard Hakluyt the Younger and those whose accounts Hakluyt collected in The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589), Smith would become a great propagandist for the western planting. They wanted to extend English military power, commerce and reformed Christianity to counterbalance the Catholic settlements already established by the Spanish in the New World. They wanted raw materials for home manufactures. Some even wanted a dumping ground for the increasing number of vagabonds displaced by the enclosures of common lands begun in the sixteenth century.1

Smith shared these motives, especially the emphasis on raw materials. His A Description of New England (1616) contains ample catalogues of New World minerals to be extracted and trees to be cut down, as well as of animals of air, sea and land to be caught for food to nourish the early settlers before they could plant their crops:

Oke is the chiefe wood; of which there is great difference in regard of the soyle where it groweth; firre, pyne, walnut, chesnut, birch, ash, elme, cypresse, ceder … Eagles, Gripes [vultures], diverse sorts of Hawkes, Cranes, Geese … Meawes, Guls, Turkies, Dive-doppers [dabchicks], and many other sorts, whose names I knowe not. Whales, Grampus, Porkpisces [porpoises], Turbut, Sturgion, Cod, Hake, Haddock … Oysters, and diverse others etc.

Moos, a beast bigger than a Stagge, deere, red and Fallow, Bever...