![]()

Creatures of fable from F. J. Bertuch, Bilderbuch für Kinder (1801). Some popular mythical creatures: 1, roc bird; 2, cockatrice; 3, phoenix; 4, unicorn; 5, tatary lamb; 6, dragon.

ONE

THE TRUE UNICORN

Now I will believe

That there are unicorns; that in Arabia

There is one tree, the phoenix’ throne, one phoenix

At this hour reigning there

Shakespeare, The Tempest (III, iii)

BY THE START of the seventeenth century, the existence of the unicorn was widely doubted among educated people. The Reverend Edward Topsell, in his History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents and Insects (1658), had this to say about the sceptics:

of the true unicorn, whereof there were more proofs in the world, because of the nobleness of his horn, they have ever been in doubt; by which distraction it appears unto me that there is some secret enemy in the inward degenerate nature of man, which continually blindeth the eyes of God to his people, from beholding and believing the greatness of God his works.1

The syntax here is a bit tangled, but he is accusing doubters of atheism, perhaps even of being under the sway of diabolic powers.

Now, Topsell was actually a person of fairly liberal inclinations, and certainly not one who habitually engaged in hunting for witches. The purpose of this finger-pointing may have been largely defensive – to head off charges of idolatry against himself. Topsell had been writing in a period of intense religious conflict throughout Britain and the rest of Europe. As a clergyman in the Church of England, he sought divine instruction in what he believed was a universal language that transcended creeds: the natural world.

Topsell did not claim to be a naturalist himself, but he studied the lore of animals in old books, largely from pre-Christian times, in search of moral lessons. To give just one example, he wrote in the dedication of his book, ‘Who is so unnatural and unthankful to his parents, but by reading how the young storks and woodpeckers do in their parents’ old age feed and nourish them, will not repent, mend his folly, and be more natural?’2 He upheld the ant as an example of industry, the lion of steadfastness, and the wren of courage. The overwhelming number of the lessons he found in nature were moral or practical, not religious. But the capture of a unicorn had become an exceptionally intricate allegory of the birth, Passion and execution of Christ.

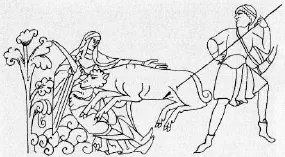

The unicorn was also mentioned by several early theologians, and found its way into the popular work known as Physiologus, probably written by Didymus of Alexandria near the end of the second century CE. According to Physiologus, the unicorn cannot be captured by force but will lay his head in the lap of a virgin, and allow himself to be led away. The author clearly identified the virgin with Mary and the unicorn with Christ, saying of it: ‘neither principalities, powers, thrones, nor dominions can comprehend him, nor can Hell hold him’.3 Upset by this deification of an animal, Pope Gelasius I condemned the story of the virgin and the unicorn as heresy in 496 and had Physiologus placed on the Church’s list of forbidden books, but the tale continued to gain in popularity. Physiologus was not only copied but expanded and incorporated into other books, and it eventually provided the basis for the medieval bestiaries, with their moralized natural history, that became popular around the eleventh century.

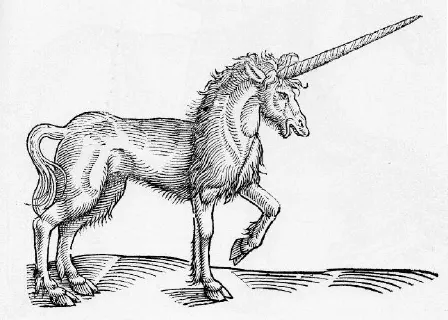

| Unicorn, from Conrad Gesner’s Historia Animalium (1551). Despite appearing in a book of natural history, this unicorn strikes a dignified, heraldic pose. |

In the European Middle Ages, the symbolism of the unicorn was far more important than any question of its physical existence. People regarded nature as composed of allegories, through which God revealed a divine plan. The authors of medieval bestiaries were not interested in documenting tales about animals, only in expounding their symbolic meanings. The lore of the unicorn reflected not only traditional Christianity but also the practice of chivalry, especially of courtly love. A knight was expected to be, like the unicorn, fierce and unyielding in battle yet endlessly gentle in his devotion to his lady, whom he would serve selflessly.

‘Virgin Capturing a Unicorn’, after an illustration in a 12th-century European bestiary. It is hard to tell whether the maiden is beckoning to the armed man or trying to shield the animal.

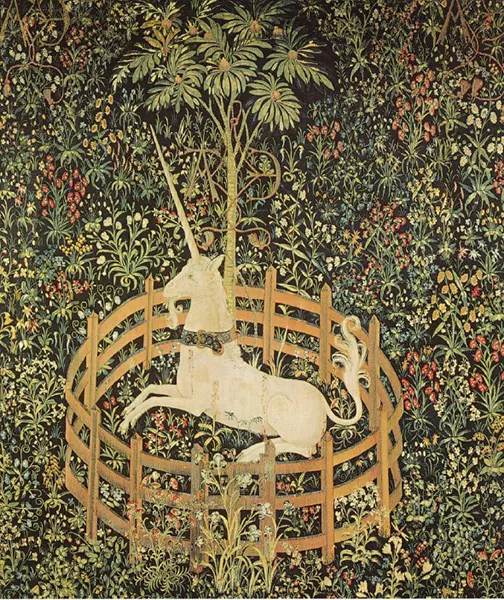

From the Unicorn Tapestries, Flanders, 1495–1505. The spear wound in the unicorn’s side is like that of Christ, and the holly around its neck recalls Christ’s crown of thorns. The man pointing on the left may anticipate the animal’s immanent resurrection. | |

The allegories in the early bestiaries were fairly simple. As the eagle rejects any eaglets that will not stare directly at the sun, for instance, so God will reject any person who cannot bear the divine light. Gradually, some of these extended metaphors became more complicated, ambivalent and mysterious. These reached a sort of culmination in the Verteuil tapestries, also known as the ‘Unicorn Tapestries’, produced around the end of the fifteenth century and now in the Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Here, a maiden and hunters are depicted going about the brutal work of capturing a unicorn as a solemn ritual, rather like a Mass, aware that they are sinners yet also cognizant that the transgression is necessary for repentance and, finally, redemption. Late medieval and Renaissance pictures of a virgin holding a slain unicorn on her lap at times resembled those of the pietà – depictions of Mary holding the dead Christ.

But why was this allegory necessary? Its purpose was surely not to explain the story of Christ to the unlettered, for it was at least as complicated as the original tale. The story seems as much designed to conceal the religious references as to elucidate them. This is the sort of concealment that one might expect from a forbidden religion, one that had gone underground, not the religion of the overwhelming majority. The problem was that conflicts among Christians had become so intense that it was hard for even the most devout believers to talk about their religion without giving offence to somebody.

‘Sight’, one of a series of six tapestries representing the senses, Brussels or northern France, 1480–1500 CE. The mirror, a traditional attribute of the Roman goddess Venus, was often used in the early modern era as a symbol of feminine vanity, but here, contrary to convention, the woman is not looking into the glass. Instead, she is placing the mirror in front of the unicorn, which has its forefeet in her lap. The intricate allegory of this and the other tapestries in the series has not been definitively explained. One theory, however, holds that the unicorn represents the lady’s deceased beloved, to whom she will remain faithful.

‘The Unicorn Defends Itself,’ from the Unicorn Tapestries, Brussels or Northern France, 1495–1505. The wounded unicorn is a symbol of Christ, and the hunters pursue it in a stylized, solemn manner, a bit like the re-enactment of the capture and Crucifixion of Jesus at a Mass.

‘The Unicorn in Captivity’, from the Unicorn Tapestries, Brussels, 1495–1505. This is the last in a series of tapestries showing the hunt, killing and resurrection of the unicorn, which form a complex allegory that has never been entirely explained. Here the unicorn, triumphant over death, is held only by a thin chain and a low fence, yet it willingly accepts the bonds of love.

Topsell wrote as the culture of the Elizabethan age was fading, and Puritanism was on the ascent. The animal guides, sages and companions found in traditional folklore and fairy tales were being demonized as familiars of witches. Any supernatural tales risked being viewed as frivolous or worse: as idolatrous or even diabolical. But, in his History of Four-footed Beasts, Topsell included not only the unicorn but also the satyr, sphinx, manticore, gorgon, basilisk, winged dragon, lamia and many other legendary beasts, even though their existence was far from being accepted in scholarly communities. His book is filled with fantastic stories drawn from many sources, from Graeco-Roman mythology to English folklore; he reported that weasels give birth through their ears and that elephants become pregnant by eating the mandrake root. For Topsell and others in the early modern period, the lore of exotic animals became a refuge for the fantasy that was increasingly discouraged by Puritan codes.

From 1642 to 1651, the Engli...