![]()

ONE

The Artist in Search of an Audience

RTISTS IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY Italy worked for an audience. The idea that they would create a painting or a sculpture simply to express themselves is almost unimaginable. Major works were commissioned, while more routine productions stocked in workshops were aimed at a known market – a nicely crafted crucifix or Madonna and Child painting could always find a buyer. Michelangelo began his artistic career in a workshop that catered particularly well to client needs. In 1488, when Michelangelo was thirteen years old, his father signed an agreement that placed the boy as an apprentice in the Ghirlandaio workshop; another document reveals that he had already worked there at least a year earlier.

1 At the time the Ghirlandaio shop was one of the most active in Florence; altarpieces, portraits and frescoes were produced efficiently and in great number by the brothers, Domenico and Davide, and their large workshop. Best known are the fresco decorations in chapels commissioned by some of the most prominent families in Florence. Located in churches that served the larger community, the paintings gave visual form to important religious narratives so that ordinary Christians could understand and

remember those stories. The chapels also served the families who commissioned them: they affirmed the family’s status since they were demonstrations of their taste and wealth, and they served as permanent memorials for deceased family members who were buried there. The Ghirlandaio workshop specialized in a type of painting that acknowledged the patrons in a most direct way: members of the family and their political allies would figure as supporting cast members within sacred dramas.

It is commonplace to cast Michelangelo as the brilliant student who completely rejected Domenico Ghirlandaio’s style; Michelangelo himself can be credited with creating that impression, since late in his life he had his biographer Ascanio Condivi state that Ghirlandaio did not help him at all. Ghirlandaio plays the role of the plodding, prosaic old master to Michelangelo’s fiercely creative, energetic young genius. But Ghirlandaio certainly taught him something. Undoubtedly he learned the technical skills needed to paint both panels and fresco. He probably learned something about colour from him as well, since Ghirlandaio’s frescoes have a freshness and variety that aid their readability in dark chapels. These are skills that would be necessary some twenty years later when Michelangelo, rather unexpectedly, was given the commission to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

We see something of what Michelangelo learned from Ghirlandaio by turning to his early drawings. Those that survive typically show only one or two heavily draped, bulky figures derived from frescoes by Giotto or Masaccio (illus. 2).2 Copying was the normal practice in a Renaissance workshop. A young artist first learned from other masters; only when the student had absorbed the styles of the best of his predecessors did he begin to develop his own style. Although none of the surviving drawings are related to Ghirlandaio’s projects, the technique still owes much to Ghirlandaio. These are finely worked, beautifully observed pen-and-ink drawings, showing layers of cross-hatching to create subtle variations of light and dark. Some are done with different coloured inks or heightened with white to give them a more colouristic effect. Ghirlandaio himself used layers of cross-hatching on his pen-and-ink figure studies, although they are looser and less controlled. When Ghirlandaio wanted to study light falling on folds of cloth he often used wash on linen or paper – a technique that closely approximated painting – or chalk on coloured paper.3 The sizes and focused nature of Michelangelo’s early drawings are quite close to Ghirlandaio’s drapery studies, but Michelangelo consistently relied on pen. Perhaps he was trying to outdo Ghirlandaio’s pen technique, but there was probably another source of inspiration too. Michelangelo’s subtle webs of cross-hatching may have been inspired by engravings, like the Temptation of St Anthony by Martin Schongauer, which Michelangelo’s friend Francesco Granacci brought to him. Vasari says he copied the engraving first in pen and then with coloured paint on panel.

2 Michelangelo, Three Standing Men, c. 1492, pen and brown ink.

And yet there are many things that these drawings are not. No composition sketches survive from this period, but this is something that Ghirlandaio, as master of the shop, took upon himself and for which he became renowned. The early drawings do not show spatial constructions, although Vasari notes that Michelangelo made a drawing of his fellow artists from Ghirlandaio’s shop at work on the scaffolding in the Tornabuoni Chapel. Was this Michelangelo’s attempt to demonstrate that he could set figures on realistically depicted stages just as Ghirlandaio did? Most conspicuously, Michelangelo’s drawings are not portraits of respected members of Florentine society – one of Ghirlandaio’s trademark methods of connecting with the viewers of his painting. Michelangelo’s lifelong aversion to portraiture may have already been at work, but painting the portraits was another task Ghirlandaio kept to himself. Ghirlandaio’s manner of inserting contemporary figures into sacred stories may have seemed too obvious or too jarring a break with the religious scene.

Though these surviving drawings were never used in a finished painting, they and the stories that surround them speak to the importance of sharing drawings. Michelangelo’s memories of his conflict with Ghirlandaio centre on not getting access to a model book. Granacci encouraged Michelangelo’s earliest artistic endeavours by bringing him drawings as well as the Schongauer print. The size and degree of finish of Michelangelo’s early drawings suggest that he hoped to use them as models for other works. These drawings were kept, and although sketches on the back or in the margins reveal that they were reused later, the early finished figures are not obscured. It is easy to imagine Michelangelo himself looking at them and remembering his earliest efforts.

Michelangelo worked in Ghirlandaio’s shop for as long as three years, but then he moved on to a very different kind of environment. Lorenzo de’ Medici, the de facto ruler of Florence, had become interested in reviving the art of sculpture there, since two of the best sculptors of the city were no longer available: Andrea del Verrocchio had died in 1488, and Antonio del Pollaiuolo was involved in projects outside of the city. It is possible that Michelangelo’s friend Francesco Granacci, five years older than him and a fellow painter in the Ghirlandaio shop, suggested that they present themselves to Lorenzo, but it is more likely that, as Vasari says, Ghirlandaio was asked for recommendations. However it happened, Michelangelo was brought to the Medici garden near San Marco to learn the art of sculpture. Bertoldo di Giovanni, a former assistant of Donatello, was head sculptor there, and he may have instructed Michelangelo and the other young sculptors in whatever technical problems they encountered. But the Medici sculpture garden was not an art academy; rather, it was a place where performances took place and where some of Lorenzo’s collection of ancient sculpture was displayed.4 The young men who came to the garden to learn sculpture learned from his collection, just as they learned about painting from the frescoes in local churches.

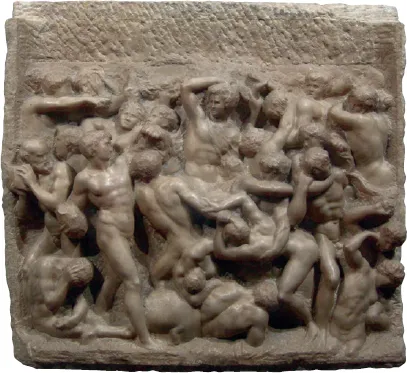

Lorenzo not only allowed Michelangelo access to his collection, but made him part of his household. Michelangelo shared experiences with Lorenzo’s son Giovanni and nephew Giulio, who as popes Leo X and Clement VII would later become his patrons, and he was taught by the learned men whom Lorenzo had gathered around him. The men in Lorenzo’s circle were brilliantly creative; their projects involved synthesizing the classical myths with Christian beliefs, searching for ever more ancient truths and exploring new modes of writing and thinking. One of those scholars, Angelo Poliziano, served as a tutor to the Medici children, and from him Michelangelo heard the stories of the Lapiths and Centaurs and the rape of Deianira. In Michelangelo’s relief Battle of the Centaurs (illus. 3), he merged them into a chaotic scene that evoked both stories but quoted neither. It may have been Poliziano who encouraged the young sculptor to leave the stone unfinished – it was he who felt that poetry was never finished.5 In Lorenzo’s household Michelangelo experienced something about what the creative process was; how to take a literary source and make something more of it and how to stop before all details were defined, leaving something for the viewer to complete. This early exposure to classical art, poetry and philosophy surely allowed him to see how art could be imbued with meaning. More importantly, in the Medici household Michelangelo learned how a true patron would allow a creative person the freedom to explore and experiment.

3 Michelangelo, Battle of the Centaurs, c. 1492, marble.

The two surviving pieces that Michelangelo created in the Medici garden are both creative adaptations of early models; they seem not to have been commissioned to serve a particular purpose. His Battle of the Centaurs is a tangle of bodies that refers to a specific literary source only in the most subtle way – through a horse’s rump and hoof at the lower edge, and the fact that the lower body of the man in the centre dissolves into what we can imagine is the body of a centaur. The piece is riotous and dense, but open to interpretation. A bald and bearded man at left prepares to hurl a rock; a younger man in the lower left corner holds his head as if injured; a woman wraps her arm around the neck of a man – is she struggling or holding on? Whether Michelangelo wanted the relief to be read in a particular way is unknown, but we do know that he treasured this early effort; years later, he told Condivi that he should have known then that he was meant to be a sculptor.

The other sculpture probably made while Michelangelo was in the household of Lorenzo de’ Medici is the Madonna of the Steps (illus. 4). This relief is in many ways opposite to the Battle of the Centaurs – in fact, it has been suggested that the two sculptures are pendants, although this can only be true in a metaphorical sense, since they are very different in format and size. In terms of subject-matter they are opposites, one pagan and the other religious. They also display very different marble carving techniques: Battle of the Centaurs is carved in half-relief, with some figures approaching full three-dimensionality, while the Madonna of the Steps is carved in very low relief, known as schiacciato. This challenging technique relies on visual effect rather than three-dimensional, tactile form. The sculptor attempts to make sculpture do what drawing or painting is best suited for, such as creating subtle recession in space and atmospheric effects. Several of Donatello’s experiments in schiacciato were easily accessible in Florence at the time (illus. 5), and similar, very low-relief sculptures were done by other artists, including Bertoldo.6 The contrasting carving techniques in the two reliefs can be seen as another similarity: both are attempts to learn from and perhaps surpass two great models. In the Centaurs relief, Michelangelo is emulating the ancients, since his model was ultimately a Roman sarcophagus owned by Lorenzo de’ Medici, while the Madonna relief invites comparison to Donatello, the greatest sculptor of the fifteenth century. The Madonna of the Steps may not have ...