![]()

1

FROM FANTASY TO PHYSICS

‘Television means . . . to subject all the complexities of the image to high tech. . . . Literatures or fantasies are therefore irrelevant. In contrast to film, television could not be dreamed of before its development. . . . Television was no wish of so-called man, but a civilian by-product of mostly military electronics.’

Friedrich Kittler, Optical Media (2002)1

As the quote suggests, despite the television’s material origins in technological invention and discovery, as well as its relationship to war, the television as an object first arises as an element in literature, specifically Victorian science fiction. From the 1880s, the new writing that connected fantasy, technology and the imperial confidence of the era was founded on the increasing security of the middle and upper classes, but held in tension by the contradictions of wealth against continuing poverty, science against religion, imperialism against liberalism, conflicts in Ireland, the rise of Germany and the suppression of the Paris Commune. Out of this emerged a scene of writing and representation that orchestrated the threats and securities that assailed the Victorian imagination, and in this context, writers began to re-imagine the world as science fiction. The form gave rise to a new sensationalist narrative involving travel, war and new media communications. Arguably taking Jules Verne’s radical step into an alternative Victorian present, in which technology, empire and travel became the themes of his novels, many writers began to explore the idea of technology facilitating sight from afar.

Early science fiction dramatized spatial conquest through technology: machines made possible the conquest of oceans and interplanetary space by balloon, submarine, gun-launched moon capsule. From Verne onwards, the literature of travel simply framed as ‘getting there’ to describe the exotica of arrival turns travel into an ‘end and not means’. Being bourgeois, the intoxicating velocities of travel could not entirely unseat its middle-class solidity; such quantitative flights of mechanical fancy therefore conducted themselves from within the ‘comfortably upholstered interior’ of these ‘space machines’.2 The literary and visual representation of Victorian television reworked the real electrical, mechanical and magnetic advances in mid-nineteenth-century technology. Science fiction projected these energies into a putative future, science concerned with distance and time. Instead of the colonial expansion across oceans and close description of the means which achieved this, the early fantasy of television collapsed time and space in order to render distance and difference a matter of safe proximity. Early science fiction used television to bring world events into the living room. The British middle class viewed wars, tennis matches and operas on their screens and conversed with Australian friends from the safety of their armchairs and parlours.

In 1884 Edward Robinson and George A. Wall wrote a prophetic novel, The Disk. Contrary to Verne’s desire to implant bourgeois standards of comfort within new travel technology, it incorporated the latest secret inventions within the middle-class home:

He then placed a small, polished disk upon an easel, and, connecting it with the wire leading to the sitting-room across the hall, broke the circuit connecting with the walls and ceiling, when, with the exception of a small circle of light coming from the disk, the room was in total darkness. Through the medium of this disk, as though a small aperture, one seemed to be looking into another room, where, in the soft, mellow light, the furniture and the hangings were distinctly visible. Mabel, too, appeared, seated in an easy-chair, and busily engaged upon some sort of needlework, unconscious of the interested eyes that were watching her movements.3

The disk is then marketed by the Photo-Electrophone Company, and from their armchairs the wealthy owners of Chicago are able to witness the explosion of the Panama Canal and the separation of the North and South American continents.

Ismar Thiusen’s ‘varzeo’, in The Diothas, or A Far Look Ahead (1883),

displayed before our eyes distant scenes, not as they had been at some past time, but as they appeared at that moment. The mirror was, in reality, a peculiar metallic screen, to which were transferred, somewhat as sound is by the telephone, the pictures falling upon a suitably prepared screen placed before the scene to be transferred.4

In his speculative novel of 1877, The Fatal Curiosity, or A Hundred Years Hence, James Payn invokes the image of ‘wall-pictures’. Set on Christmas Day 1979 at 10 a.m., its protagonist, Sir Rupert, muses on the diminishing expense of his Pandi-optic’s ability to ‘get instantaneous reflections on my wall, and at a very reasonable figure, of what all my friends are doing all over the world’.5 He reflects on the technology required to reverse the upside-down images of people in Australia. Here the comparison is technological. From the 1870s to the 1890s bourgeois domestic science fiction pre-empted this imminent arrival of telephony and the possibility of images crossing the air between two machines.

Robert Cromie’s story A Plunge into Space (1890) captures the journey of the television image:

A message of sight or sound is flung upon the air, is plunged into the sea, is fired into the ground. At the end of its journey – be that a mile or a million – it is picked up by the waiting machine . . .6

Yet as the imagination of these early explorers projected a Victorian society of the future, it instigated an emerging literary genre in which the contradictions of expansion through commerce and technology met with the contraction and condensation of the middle-class vision of the world as a private space in which the outside environment could be filtered through a bourgeois prism of tastes and fancies. In this transaction, the visual and literary language of the pre-technological image of the television found its discourse. This dream of television connected with the desire to unite the Victorian domestic inhabitant with prevailing forms of leisure and spectacle, such as the opera and the popular music halls, or similar spectacles open to discerning and select audiences. In Ismar Thiusen’s The Diothas; or, A Far Look Ahead (1883) the ‘varzeo’ enabled its viewers to supply an accompaniment that for readers of this reassuring futurology took the edge off an otherwise alien intrusion: ‘While the audience gazed in silence on this living picture, Ulmene, at the fine instrument belonging to the hall, softly played an improvisation, introducing such selections from the national airs as her exquisite taste judge appropriate to the scene.’7

Albert Robida’s 1883 novel Le Vingtième siècle envisions life in 1952, in which the character Hélène Colobry searches for a profession in a world of technological opportunity. The world has harnessed the téléphonoscope as a familiar and instant communication device:

The device consisted of a simple crystal plate, built into the wall or placed as a mirror above any fireplace. The theatre lover, without leaving the home, simply sits in front of the screen, chooses his theatre, sets up the communication and the show begins immediately.8

Albert Robida’s novel La Vie électrique projected a 1950s world, one in which technology is prone to malfunction:

thousands of confused images and sounds from all the rumours filled houses like the roar of a new and fiercer storm . . . condensed into a general noise, and then rendered en bloc through each of these devices with a frightful intensity!9

Robida’s futuristic machines envisaged a coherent social and cultural network, in which his televisions reflect and engender customs and attitudes. They affect attitudes to gender equality and patriarchy, and scientific progress. In La Vie électrique, female emancipation and patriarchy find contradictory expression in the new technology that facilitates freedom from the domestic space with increased control from afar. The engineer Sulfatin has jealous designs on an actress, Sylvia, whom he can view on the téléphonoscope behind the scenes at the theatre and whom he asks: ‘You tell me right away [Sylvia] who was that gentleman who just went by? I want information!’ Sylvia replies:

I tell you I’m tired of your incessant scenes! I have had enough surveillance from TV [le télé] or phonograph! Do you know that you insult me with all your machines which record my actions. I do not want to support these ways!10

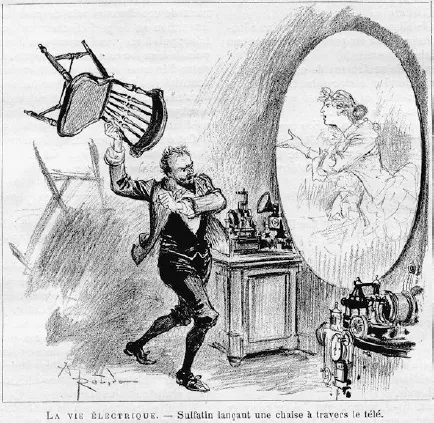

Sulfatin throws a chair at the screen and the image of Sylvia shatters.

| Albert Robida, ‘Sulfatin Threw a Chair through the Telly’, La Vie électrique (1890 edn). |

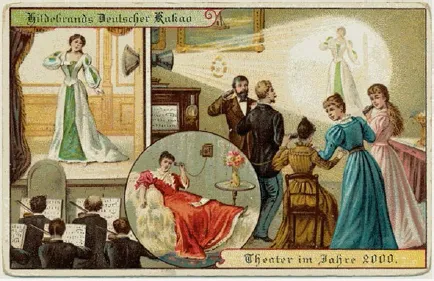

A Victorian trade card from the A Hundred Years Hence series, imagining televisual projection of an opera in the 1990s. | |

Television’s cultural fantasies did not exist in isolation from the discoveries, research and invention of mid-nineteenth-century communications technology and the major developments in the investigation and harnessing of electro-magnetism. However, this branch of physics only appeared abstractly or figuratively through the characters that stood for progress, experiment and the future: the engineer, doctor, industrialist or gentleman amateur-inventor. Although the advent of telegraphy at the dawn of the electric age brought the new fields of physics into popular discourse, other discourses intruded on these fledgling sciences. As Stefan Andriopoulos observes, a determinist view of the history of the television failed to locate its source in one field, whether engineering, physics or occultism; rather ‘it is the interaction between these ostensibly strictly separated spheres that marks not so much the “invention” as the gradual emergence of the medium known as television.’11

Clairvoyance, telepathy and spiritualism foreshadowed and accompanied the theoretical and practical development of telegraphy, telephony, radio and electrical television. Their roots lay in the late eighteenth-century philosophical idealism that likened technology such as the magic lantern to a demonstration of the uncertainty of sensory perception, and the mistaken identification of subjective ideas for objective conditions. This highlighted a concern with interrogating the limits of philosophy in order to see the empirical world as construed by intuition, indicating however an unknowable substratum beyond the senses.

Such ‘shadow’ discourses comprised a constellation of sciences that later receded with the rise of positivist science. They foregrounded the sense of the body and mind as a medium exposed to gradual electrification and communication by wire and rays passing through the ‘ether’. These residual natural sciences included the revival of mesmerism, a popular craze from the 1840s, which promoted the flow of ‘animal magnetism’ between bodies and hypnotism to cure maladies, connect minds and generate visions of the future. They drew on prevailing assumptions of social and psychological adjustment in a time of rapid transformation, not least in the changing role of women. This appeared in popular fiction, in novels devoted to questioning female self-control: ‘the subject’s body, mind and possession are vulnerable to appropriation’ where hypnotic scenes ‘deprive the female subject of “ownership” of her thoughts, feelings, words and actions’.12 Metaphors of control abounded; loss of control, remote control. The fantastic literature of the nineteenth-century telescope delineated and ascribed gender roles in constructions of the television, where men watched and women appeared on screen. These narratives compounded anxieties about new legislation on women’s ownership of property, self-governance and increasing access to labour markets as typists or telegraphers.

Bodies were becoming media and communication channels within an electrified environment that saturated them. Such visions dramatized and extended the early technological advances in research on electricity, including precursors to the cathode ray tube. A debate on the emanation of light in cathodes being a wave or a torrent of molecules became a focus that would draw in wider discussions on the connection of energy flows between the living and spirit world. The English engineer and electrician Cromwell Fleetwood Varley had pioneered telegraphy using transatlantic cables before turning to the mystery of electrical discharge through rarefied gases and the indistinct boundary between visible and invisible states. Varley’s interest in spiritualism and ‘remote sensing’ (or seeing events clairvoyantly, a skill that his wife practised) followed his successful network of electric telegraphy and would enable him to understand and even gain access to a ‘spiritual telegraph’. Varley tested mediums and their ‘spirits’ to illustrate his belief that the expertise and resources he had used in constructing successful electric telegraphs could unite science and the occult.13

Varley’s assumption was built on earlier claims for a medium that connected two worlds, the material with the immaterial and the spirit world with the living. The German chemist Karl von Reichenbach had proposed a new force, which he termed ‘od’, and claimed experimental evidence for it that could only be perceived by sensitive recipients attuned to multicoloured auras around objects such as magnets or crystals. This ‘sober scientific investigation’ would dispense with the ‘wretched magical trash’ of Mesmer and install a new kind of radiation – the Od ray.14 Observation and repeatability of experiments gradually coaxed this ray into scientific light. In 1855 Heinrich Geissle...