- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

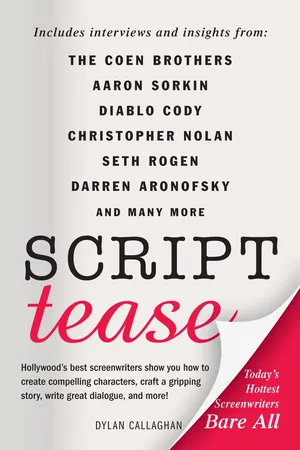

About this book

The Newest Screenwriting Secrets

What do an erstwhile stripper, an ex–gambling addict, and a stoned Canadian teenager have in common? They wrote your favorite movies, and they're not who you'd expect.

Diablo Cody (Juno), Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler), and Seth Rogan (Superbad) are among the scribes interviewed in Script Tease, your main line to the most current screenwriting wisdom. Their funny, even touching tales of how they made it despite the odds will give you a revealing look into what it really takes to get into the industry.

With the guidance of recent greats like Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network) and the Coen Brothers (True Grit), you will learn how to hone your craft and make it in an industry where only the best succeed.

What do an erstwhile stripper, an ex–gambling addict, and a stoned Canadian teenager have in common? They wrote your favorite movies, and they're not who you'd expect.

Diablo Cody (Juno), Darren Aronofsky (The Wrestler), and Seth Rogan (Superbad) are among the scribes interviewed in Script Tease, your main line to the most current screenwriting wisdom. Their funny, even touching tales of how they made it despite the odds will give you a revealing look into what it really takes to get into the industry.

With the guidance of recent greats like Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network) and the Coen Brothers (True Grit), you will learn how to hone your craft and make it in an industry where only the best succeed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Script Tease by Dylan Callaghan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Creative Writing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ERIC ROTH

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS:

Forrest Gump; Ali; The Horse Whisperer; The Insider

“It will come to you, whether it’s in a dream or some song you hear or a feeling you have or some memory. I don’t know what the reasons are, whether they’re subconscious or unconscious, but something always seems to save the day.”

—ERIC ROTH

Eric Roth speaks in an almost tepid tone, like a weary man thinking out loud in an empty room. But it’s not apathy. The Oscar- winning scripter’s pleasantly rumpled, modest manner stems from a thoughtful mind that long ago realized a distaste for loud speakers with little to say.

So, like a Zen master who never wanted to be asked, the veteran writer answers questions in a bare, hovering voice that makes you listen more carefully for all its quietness. Of course, what he says helps hold listeners after they lean in. There is also the matter of his career, as notable for huge successes as for the genre-jumping diversity of his credits, from Forrest Gump to The Horse Whisperer and The Insider to Ali.

A good story is what connects them all.

Here, in an expansive, at times personal chat, Roth talks about The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, his own mortality, and the unavoidable truth of classic dramatic structure.

He says he writes more to theme than he does to story and that the first twenty or so pages of a script are where all the work happens. He rewrites those first pages over and over until he breaks the script and knows where it goes from there.

Was the scope and time frame of this narrative [of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button] as similar to Forrest Gump as it seems like it might have been?

I guess you could say that, but you could also probably say Ali is like that. I think it’s not inaccurate, but this is really from cradle to grave and Forrest Gump isn’t. It was certainly from a boy to a man.

To what extent was the scope reminiscent of work you’d done before, or was it a pretty singular experience?

I tried to make it singular, let’s put it that way. Whatever is reminiscent is not by design.

Right, and I don’t mean to say that …

No, no, I think it’s a fair question because obviously I created both, so I’m bringing something with me. There’s probably some similarity in style, but I think they’re very different movies. I think Benjamin deals with different subjects.

What is this story about to you?

I think it’s a look at mortality in a way, the natural qualities of life and death. There’s nothing really extraordinary about his life except for the fact that it’s extraordinary because he ages backwards. He’s sort of an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances.

Other than being a novelty, what does the fact that he ages backwards do to the story?

I think it makes you think about all sorts of things. On face value, you’d think it would be great. You’d become young again, you’d have great vision again and great stamina and great love, things that sound sort of wondrous. And yet, when one would experience it, it seems to me there is a major component of loneliness. And also, you’re simply aging toward your demise in a different way.

The simple conclusion, without giving too much of the movie away, is that, whether you live your life backwards or forwards, it’s best to live it well.

How did this story strike you on a personal level?

I can talk to you about my parents’ death. They both died during the writing of this. They informed the whole writing of this.

Oh, I didn’t know that.

That’s why I was a little hesitant [when you asked earlier on background] about them … I don’t want to … I love them.

Did they pass in the same year?

They passed about three years apart, but the [writing] process began when my mother was passing away. I’m not trying to be exploitive of either of their deaths, but it did make me a more mature writer. It’s like the Joan Didion quote about how you have to go to this land of grief that you’re not prepared to go to, but that you have to go to when a loved one dies.

When your parents die it’s obviously a very unique brand of grief because you’re losing a person that’s beloved, but it also must bring up questions of your own mortality.

Completely. I remember one particular day, my son, who was twenty-five or so at the time, was having a child and my father had had a stroke so they were at the same hospital. I was going from one room to another. So my son having a child makes me a grandfather and I’m also a son going to visit his father. It just happened that they all fell at the same time.

That does bring up your mortality. Look, I know I’m not only on deck, I’m up to bat right now. But that’s not necessarily bad. If one believes in the natural qualities of life and death, there’s nothing wrong with it. That’s one of the things about the movie that we deal with.

That story you describe in the hospital sounds so Buttonesque, literally going from your newborn grandchild to your father. And this was right at the beginning of the writing process?

This was more in the middle of it.

Did you feel the universe was messing with you at all?

I don’t know … I’m not sure the universe is that interested in me. I think you just hopefully come to terms with the conditions of life. There’s going to be all sorts of experiences—good, bad, and indifferent. You have to face these things.

Is it a matter of acceptance?

Yeah. I mean, I’m not telling you I’m all that accepting, but I think acceptance is key to some form of peace. But what would I know?

Well, you might know a few things.

I don’t think I know anything. I really don’t. Not any more than anyone else.

Because of your parents’ passing, your new grandchild, and writing this movie, did the completion of this script feel different than other films you’ve written?

Yeah, I would say more than anything else I’ve written, this one is the most personal. It’s also one that has helped me find some acceptance. That’s a great question. I love that.

If you can get technical for a minute, with this particular story, what was your first step in terms of grappling with it given its scope and its source material?

There were two, I think. One was trying to decipher what I was going to use from the short story, which became almost nothing. That was painful because obviously F. Scott Fitzgerald is a hundred times the writer I could ever be. But I had to make a decision about what spoke to me in doing this.

I knew that he had written this as a whimsy. I spoke to a few of his biographers and neither felt that he thought this was one of his important works. It was something that had been dashed off.

INTERVIEWER

Was it important for you to know that?

ERIC ROTH

Well, to me it was. Most important was the core of it, which is the idea of a man aging backwards, which actually came from an essay Mark Twain had written about how interesting it would be if we could age the other way and avoid all the infirmities of old age. Maxwell Perkins, F. Scott’s editor, gave him the [Twain] essay, and he wrote a story for a magazine. He’d also just had a baby so he probably needed some money for diapers and alcohol.

Diapers and booze: a classic combo.

Diapers and booze, what else is there? So eighty years later it’s given to me. A number of people had taken a shot at it, including the wonderful Robin Swicord, but for whatever reason it hadn’t really landed. So they gave me a little bit of free rein.

So despite F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story and Robin Swicord’s previous drafts, you were essentially operating with a blank slate except for the general concept?

Yes.

Having dealt with the decision about the source material, what was the next step?

The next thing was finding the theme, which is something I’m always interested in. As I said earlier, I wanted to tell a story that lent itself to the idea that, whether you live your life backwards or forwards, you should live it well. That’s how I wanted to tell the story.

The next step was the technical decision of how I wanted to tell the story, which was through a framing device. It doesn’t feel like a device, I think it feels very natural being told by this old woman who’s dying. Once I had that, I knew what the beginning and end was because I knew what was going to happen to her. I knew I was going to start it with a baby being born under unusual circumstances. I decided I was going to take the story through his life—with jumps in time and all—but that it would go from cradle to grave, or grave to cradle as it were.

So first off you found your sort of thematic ethos?

Which, if you want to talk about screenwriting, is true of all my work. I’m as interested in the theme as I am in what the story is. I feel like I write more toward theme than I do toward story.

Once you comprehend your theme, it sort of navigates you through the narrative?

Yeah, I think it does. Then I start to populate it. Part of the storytelling is all these people that come through your life. Some make an impact and some don’t. And in the long run, these people have helped give you your point of view on life. It’s this pastiche of people that helps create the fabric of who you are.

Also, you might find it interesting with this movie, I don’t think there’s a bad person in it. There are complicated people and people who don’t live up to what we’d hoped they’d be, but nobody really arch, I hope.

How much did this population of characters refer to people you’ve known?

I don’t think too much except for the woman dying. There are all kinds of personal things that enter into it, but no specific people, I think, except for her. And then there are several metaphorical things about destiny and chance and fate, which is an overriding thing.

And the woman telling the story is referential to your mother?

Completely. Some of it, I just used actual words she said to me. When she was dying I asked her if she was afraid and she said, “No, I’m curious.” That’s in the movie.

And then there’s the notion, what if a person is telling you things you didn’t know about them in the last moments of their life? There was nothing startling about my mother at the end of her life that she hadn’t told me, but you still sort of learn things about people as they’re going away that makes you appreciate them even more.

So you go from theme to characters …

Then I had to think about the story. The storytelling is very picaresque. It has a structure, but it’s very episodic. I’ve done that in a couple films before, even though I can write in the classical, three-act dramatic structure.

Structure is so dominant in modern screenwriting. It’s obviously crucial to effective screenwriting, but how do you balance it against emotion, abstraction, and originality in a script?

I don’t think you can avoid the classical dramatic structure. You can stand on your head and try to have four acts instead of three, but you’re still going to have a beginning that presents a problem, a second act that complicates it, and a third or fourth [act] that resolves it or doesn’t resolve it. I don’t think you can escape it.

Sure, in that macro sense, but on a more micro sense, during the actual writing process some approaches are more reliant on mapping and outlining the skeletal structure to feed the narrative, versus the narrative feeding the structure.

Yeah, with me, even though I’m well aware of structure and where the act breaks should be, the narrative is first. It’s difficult to say which is the chicken and which is the egg. You know, in the back of your head that the structure is there, the act, and so forth.

Do you think you’ve ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Darren Aronofsky

- Shane Black

- Ian Brennan and Brad Falchuk

- Diablo Cody

- Joel and Ethan Coen

- Sofia Coppola

- Emilio Estevez

- Geoffrey Fletcher

- Vince Gilligan

- Garrison Keillor

- Steve Kloves

- Elmore Leonard

- Richard Linklater

- Allan Loeb

- Danny McBride and Jody Hill

- Christopher and Jonathan Nolan

- Adam Rapp

- Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg

- Melissa Rosenberg

- Gary Ross

- Terry Rossio and Ted Elliott

- Eric Roth

- James Schamus

- Aaron Sorkin

- Nicholas Sparks

- Sylvester Stallone

- Mike Sweeney

- Emma Thompson

- Gus Van Sant

- Rob Zombie

- Copyright