eBook - ePub

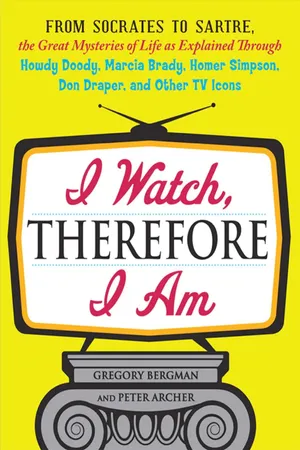

I Watch, Therefore I Am

From Socrates to Sartre, the Great Mysteries of Life as Explained Through Howdy Doody, Marcia Brady, Homer Simpson, Don Draper, and other TV Icons

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

I Watch, Therefore I Am

From Socrates to Sartre, the Great Mysteries of Life as Explained Through Howdy Doody, Marcia Brady, Homer Simpson, Don Draper, and other TV Icons

About this book

Let Gilligan's Island teach you about situational ethics.

Learn about epistemology from The Brady Bunch.

Explore Aristotle's Poetics by watching 24.Television has grappled with a wide range of philosophical conundrums. According to the networks, it's the ultimate source of all knowledge in the universe! So why not look to the small screen for answers to all of humanity's dilemmas?There's not a single issue discussed by the great thinkers of the past that hasn't been hashed out between commercials in shows like Mad Men and Leave It to Beaver. So fix yourself a snack, settle into the couch, grab the remote...and prepare to be enlightened.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Watch, Therefore I Am by Gregory Bergman, Peter Archer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

What’s the World

Made Of?

Donuts! And Beer!

Histories of philosophy divide early philosophers into two groups: the pre-Socratics and everybody else. Pre-Socratics are called that because they came before Socrates. (Not too tough, huh? Maybe this philosophy stuff will be easier than you thought.)

The pre-Socratics are also sometimes called the Ionians, because they came from a part of the coastline of what is now Turkey. At the time, this area was called Ionia—so naturally the people from that area were called…you guessed it.

See? Philosophy’s pretty easy, right? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Some of the Ionian philosophers in particular were important enough that Aristotle (whom we’ll talk about later) wrote about some of what they believed. All of them were interested in one of the most important questions of the day: What’s everything made of?

Now if Homer Simpson had been around at that point, it’s easy to imagine his answer to this problem. Clearly, the most important thing in the world is donuts, washed down by cooling draughts of Duff Beer.

“Donuts! Is there anything they can’t do?”

—Homer Simpson

Like Homer, the philosophers of Ionia looked around for the most important thing they could find in their world and then imagined the entire world was made of it.

THALES OF MILETUS

Thales, who lived around the beginning of the sixth century B.C. (the one date that’s reliably associated with him is 585 B.C.), figured he had this philosophy stuff down. The world and everything in it, he proclaimed, is made of water. Not only is everything made of it, he said, but it’s the original substance that everything else came from in the first place. This isn’t completely unreasonable. After all, we need water to live; we’re usually not that far away from some body of water (unless you’re reading this in the middle of Death Valley or the Sahara Desert).

You can imagine, though, what might have transpired if Thales had ever met Homer—possibly over a drink at Moe’s.

Thales: The world is made of water.

Homer: Who’s the guy with the funny accent?

Moe: Uh, that’d be Thales. He, uh, he ain’t from around here. He’s from Greece. He’s one of dem philosopher guys.

Homer: Oh, really. Well, let me tell you, Mr. Big Shot Greek Hoity Toity Philosopher Guy that here in Springfield we’re patriotic Americans. And we know that everything is made of beer! And donuts!

Thales: [taking a drink of Duff] Beer, you say. Well, perhaps you are right.

Homer: Hey, Moe! We should get Apu in here. This guy kinda talks like him.

Your perception of what the world is made of, in other words, has a great deal to do with what is most important to you. The Ionian Greeks’ world was dominated by water—a source of food, drink, transportation, and irrigation. So we can certainly see Thales’ point.

THALES WAS A GENIUS!

The human body is composed of somewhere between 55 percent and 78 percent water. Old Thales is sounding smarter and smarter.

Thales’ contemporary, Anaximander, disagreed with Thales to the extent that he thought everything comes from some primal substance that’s not water. This substance was the basis of the four most important elements: fire, water, earth, and air. Again, this is pretty understandable from our point of view. Thanks to Einstein, we know that matter and energy are different forms of each other—a bit like Anaximander’s cosmic “stuff.”

Finally, another Ionian, Anaximenes, argued that everything is made of air.

All the Ionian philosophers said, as would many other philosophers, that even though the world appears to be made up of many different things, beneath this appearance is a basic unity. This is an important concept in the history of philosophy: What a thing looks like and what it is aren’t necessarily the same.

The disparity between form and substance, something that philosophy has spent a lot of time on, is one of the staples of television sitcom jokes. Consider this exchange from the late seventies sitcom Mork and Mindy (the show that broke out Robin Williams’s career). Mindy, played by Pam Dawber, has been tossed in jail and is talking to her cellmate, Louise Bailey, played by Barbara Billingsley:

Louise Bailey: Funny the way things happen. I’m in here because of a silly old parking meter.

Mindy McConnell: You’re kidding!

Louise: No, I went into a hardware store and when I came out, there was a policeman writing me a ticket.

Mindy: I don’t believe it. They threw you in jail for a parking ticket.

Louise: Well, in a roundabout way. You see when I put the shovel in the trunk, Walter’s arm fell out.

Mindy: Who’s Walter?

Louise: My husband.

Mindy: What was he doing in the trunk?

Louise: Not much…he was dead.

Mindy’s made an assumption about reality based on surface appearances. It takes Louise to explain to her the underlying truth of the situation.

Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes wanted to go beneath surface appearances and understand the real truth of the world. Once they figured out what everything was made of, they assumed the rest would be easy.

In the same way, Homer tends to assume a simple answer to most of life’s problems. This isn’t exactly naive—just hopeful.

“Here’s to alcohol: the source of, and answer to,

all of life’s problems.”

all of life’s problems.”

—Homer Simpson

This issue of substance versus appearance was taken up in a much more profound way by Plato in his theory of Forms (more about that later).

PYTHAGORAS

Anyone who stayed awake in high school math class probably recognizes the name Pythagoras—wasn’t he the guy who made up that theorem? Something about a square on the hypotenuse of a right-angle triangle…well, anyway, he had something to do with math, right?

Right. Except that, ironically, he may not have made up the Pythagorean theorem after all. Still, he was the first philosopher to be preoccupied with numbers. He was sort of the sixth-century B.C.’s version of The Simpsons’ Mathemagician, a party entertainer working with math. Pythagoras must have been a blast at Greek parties.

Pythagoras’s basic point is that appearances are deceptive and unreal (remember Thales and company?), and only numbers are real. That’s comforting if you’re into numbers, but for most of us, not so much.

“No! I can’t take another minute in the cold unyielding

world of numbers!”

world of numbers!”

—Mikey from Recess

Actually, a lot of Pythagoras’s attitudes about the underlying reality of mathematics played out on the TV show Numb3rs. The show’s main character, Charlie Eppes, helped his brother Don, who was an FBI agent, solve crimes through applied mathematics.

“Some people drink, some gamble. I analyze data.”

—Charlie Eppes

Charlie, a brilliant mathematician, constantly runs into the problem of the disparity between the elegance of equations and the ugliness of reality. Rather like Pythagoras, he’s inclined toward numbers as the true expression of “reality.” However, others challenge that rigid viewpoint.

Charlie: Larry, something went wrong, and I don’t know what, and now it’s like I can’t even think.

Dr. Larry Fleinhardt (played by Peter MacNicol): Well, let me guess: You tried to solve a problem involving human behavior, and it blew up in your face.

Charlie: Yeah, pretty much.

Larry: Okay, well, Charles, you are a mathematician, you’re always looking for the elegant solution. Human behavior is rarely, if ever, elegant. The universe is full of these odd bumps and twists. You know, perhaps you need to make your equation less elegant, more complicated; less precise, more descriptive. It’s not going to be as pretty, but it might work a little bit better. Charlie, when you’re working on human problems, there’s going to be pain and disappointment. You gotta ask yourself, is it worth it?

Charlie responds by finding ways to adapt his equations to account for human behavior, to try to understand the mathematical realities behind the way things really are. It’s a quest of which Pythagoras would be proud.

WHO’S THE REAL MATH WHIZ?

David Krumholtz, who plays Charlie on Numb3ers, failed algebra in high school and hated math. Ironically, Dylan Bruno, who plays a math-challenged FBI agent on the show, graduated from MIT with an engineering degree, for which he had to know a ton of math. Just goes to demonstrate the magic of television, doesn’t it?

HERACLITUS AND THE RIVER

The pre-Socratics hadn’t yet exhausted the topic of what everything was made of. Heraclitus, a contemporary of Pythagoras, thought everything was made of fire. (You can see how the Greeks were working their way through the elements: Thales, water; Anaximenes, air; Heraclitus, fire.…) This led him to an interesting conclusion: Since fire is constantly flickering and changing its shape and color, the only constant is change. Change is the real reality, and the stability that we see around us is an illusion. Famously, he said that time was like a great river, and you couldn’t step into the same river twice.

Along with this belief, he concluded that the order of things is created by the conflict of opposites with one another, the whole thing controlled by what the Greeks called logos, which we roughly translate as “reason.”

Let’s hark back a moment to Numb3rs. The show is really about two brothers, Charlie and Don. Charlie is all mind, the ultimate nerd (although one with a drop-dead gorgeous girlfriend—who’s also a numbers nerd; how likely is that?). Don, on the other hand, is the muscle in the family, the rough-and-tough agent who kicks down doors and plunges into crack dens, gun drawn and ready.

And then there’s the father, played by Judd Hirsch. He’s the voice of reason (logos, if you will), who reconciles the opposites, promotes both their strengths, and makes it possible for them to work together in harmony. That’s what Heraclitus was talking about.

You can find this same pattern in other TV sitcoms: the two characters with opposing temperaments, regulated by the calm, wise figure of logos. That was more or less the idea on ensemble shows like The Partridge Family (where the logos was played by Shirley Jones) and Eight Is Enough, starring Dick Van Patten.

DEMOCRITUS AND THE ATOMISTS

One of the very frustrating things about this early period of Greek philosophy is how much we don’t know about it. None of the people we’ve been talking about left any writings, and we have to guess at their doctrines based on what other people—mainly Aristotle—said about them.

Democritus was probably a very remarkable man, but we don’t know when he was born...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 What’s the World Made Of? Donuts! And Beer!

- Chapter 2 Protagoras, Gorgias, Captain Kirk, and Denny Crane

- Chapter 3 Socrates The Sergeant Schultz of Ancient Greece

- Chapter 4 Plato Is the New American Idol

- Chapter 5 Aristotle Loves Lucy

- Chapter 6 Charlie Harper’s Non-Epicurean Lifestyle

- Chapter 7 St. Augustine’s Highway to Heaven

- Chapter 8 Scully Shaves Mulder with Ockham’s Razor

- Chapter 9 Larry Hagman Dreams of Descartes

- Chapter 10 Locke versus Hobbes, or The Brady Bunch Takes on Survivor

- Chapter 11 Can or Can’t Kant Like Vampires?

- Chapter 12 Reading Hegel in Outer Space

- Chapter 13 John Stuart Mill and the Utilitarian Heroism of Dexter Morgan

- Chapter 14 Karl Marx and Adam Smith, Meet Alex P. Keaton

- Chapter 15 Dr. Gregory House and the Nietzschean Superman

- Chapter 16 Don Draper, George Costanza, and the Non-Meaning of Life

- Chapter 17 Jersey Shore’s “The Situation” The Randian Ideal Man with a Tan?

- Chapter 18 Earl Hickey Meets Karma in My Name Is Earl

- Chapter 19 Lost But Not Least

- Conclusion

- APPENDIX A Glossary of Philosophical Terms

- APPENDIX B Who’s Who in Philosophy

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author