- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

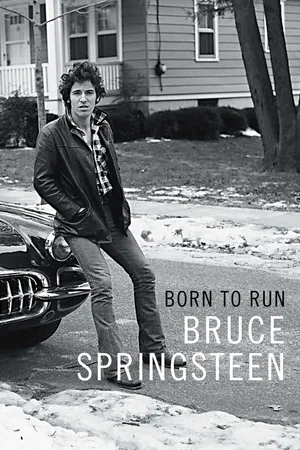

Born to Run

About this book

The revealing, wildly entertaining, and bestselling memoir from the legendary Bruce Springsteen, one of the greatest songwriters and performers of any era. Born to Run is the greatest rock ‘n’ roll story ever told.

Essential reading for the 50th anniversary of Springsteen’s seminal album Born to Run, the long-awaited release of Nebraska ’82, and a companion to the acclaimed film Deliver Me from Nowhere, starring Jeremy Allen White and Jeremy Strong, about the writing and recording of Springsteen’s classic Nebraska record.

Following his 2009 Super Bowl halftime performance, Bruce Springsteen privately devoted himself to writing the story of his life. The result is “an utterly unique, endlessly exhilarating, last-chance-power-drive of a memoir” (Rolling Stone) that offers the same honesty, humor, and originality found in his songs.

He describes growing up Catholic in Freehold, New Jersey, amid the poetry, danger, and darkness that fueled his imagination, leading up to the moment he refers to as “The Big Bang”: seeing Elvis Presley’s debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. He vividly recounts his relentless drive to become a musician, his early days as a bar band king in Asbury Park, and the rise of the E Street Band. With disarming candor, he also tells for the first time the story of the personal struggles that inspired his best work.

Rarely has a performer told his own story with such force and sweep. Like many of his songs (“Thunder Road,” “Badlands,” “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” “The River” “Born in the USA,” “The Rising,” and “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” to name just a few), Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography is written with the lyricism of a singular songwriter and the wisdom of a man who has thought deeply about his experiences.

“Both an entertaining account of Springsteen’s marathon race to the top and a reminder that the one thing you can’t run away from is yourself” (Entertainment Weekly), Born to Run is much more than a legendary rock star’s memoir. This book is a “a virtuoso performance, the 508-page equivalent to one of Springsteen and the E Street Band’s famous four-hour concerts: Nothing is left onstage, and diehard fans and first-timers alike depart for home sated and yet somehow already aching for more” (NPR).

Essential reading for the 50th anniversary of Springsteen’s seminal album Born to Run, the long-awaited release of Nebraska ’82, and a companion to the acclaimed film Deliver Me from Nowhere, starring Jeremy Allen White and Jeremy Strong, about the writing and recording of Springsteen’s classic Nebraska record.

Following his 2009 Super Bowl halftime performance, Bruce Springsteen privately devoted himself to writing the story of his life. The result is “an utterly unique, endlessly exhilarating, last-chance-power-drive of a memoir” (Rolling Stone) that offers the same honesty, humor, and originality found in his songs.

He describes growing up Catholic in Freehold, New Jersey, amid the poetry, danger, and darkness that fueled his imagination, leading up to the moment he refers to as “The Big Bang”: seeing Elvis Presley’s debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. He vividly recounts his relentless drive to become a musician, his early days as a bar band king in Asbury Park, and the rise of the E Street Band. With disarming candor, he also tells for the first time the story of the personal struggles that inspired his best work.

Rarely has a performer told his own story with such force and sweep. Like many of his songs (“Thunder Road,” “Badlands,” “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” “The River” “Born in the USA,” “The Rising,” and “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” to name just a few), Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography is written with the lyricism of a singular songwriter and the wisdom of a man who has thought deeply about his experiences.

“Both an entertaining account of Springsteen’s marathon race to the top and a reminder that the one thing you can’t run away from is yourself” (Entertainment Weekly), Born to Run is much more than a legendary rock star’s memoir. This book is a “a virtuoso performance, the 508-page equivalent to one of Springsteen and the E Street Band’s famous four-hour concerts: Nothing is left onstage, and diehard fans and first-timers alike depart for home sated and yet somehow already aching for more” (NPR).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Music BiographiesBOOK ONE

GROWIN’ UP

ONE

MY STREET

I am ten years old and I know every crack, bone and crevice in the crumbling sidewalk running up and down Randolph Street, my street. Here, on passing afternoons I am Hannibal crossing the Alps, GIs locked in vicious mountain combat and countless cowboy heroes traversing the rocky trails of the Sierra Nevada. With my belly to the stone, alongside the tiny anthills that pop up volcanically where dirt and concrete meet, my world sprawls on into infinity, or at least to Peter McDermott’s house on the corner of Lincoln and Randolph, one block up.

On these streets I have been rolled in my baby carriage, learned to walk, been taught by my grandfather to ride a bike, and fought and run from some of my first fights. I learned the depth and comfort of real friendships, felt my early sexual stirrings and, on the evenings before air-conditioning, watched the porches fill with neighbors seeking conversation and respite from the summer heat.

Here, in epic “gutter ball” tournaments, I slammed the first of a hundred Pinky rubber balls into my sidewalk’s finely shaped curb. I climbed upon piles of dirty snow, swept high by midnight plows, walking corner to corner, the Edmund Hillary of New Jersey. My sister and I regularly stood like sideshow gawkers peering in through the huge wooden doors of our corner church, witnessing an eternal parade of baptisms, weddings and funerals. I followed my handsome, raggedly elegant grandfather as he tottered precariously around the block, left arm paralyzed against his chest, getting his “exercise” after a debilitating stroke he never came back from.

In our front yard, only feet from our porch, stands the grandest tree in town, a towering copper beech. Its province over our home is such that one bolt of well-placed lightning and we’d all be dead as snails crushed beneath God’s little finger. On nights when thunder rolls and lightning turns our family bedroom cobalt blue, I watch its arms move and come to life in the wind and white flashes as I lie awake worrying about my friend the monster outside. On sunny days, its roots are a fort for my soldiers, a corral for my horses and my second home. I hold the honor of being the first on our block to climb into its upper reaches. Here I find my escape from all below. I wander for hours amongst its branches, the sound of my buddies’ muted voices drifting up from the sidewalk below as they try to track my progress. Beneath its slumbering arms, on slow summer nights we sit, my pals and I, the cavalry at dusk, waiting for the evening bells of the ice-cream man and bed. I hear my grandmother’s voice calling me in, the last sound of the long day. I step up onto our front porch, our windows glowing in the summer twilight; I let the heavy front door open and then close behind me, and for an hour or so in front of the kerosene stove, with my grandfather in his big chair, we watch the small black-and-white television screen light up the room, throwing its specters upon the walls and ceiling. Then, I drift to sleep tucked inside the greatest and saddest sanctuary I have ever known, my grandparents’ house.

I live here with my sister, Virginia, one year younger; my parents, Adele and Douglas Springsteen; my grandparents, Fred and Alice; and my dog Saddle. We live, literally, in the bosom of the Catholic Church, with the priest’s rectory, the nuns’ convent, the St. Rose of Lima Church and grammar school all just a football’s toss away across a field of wild grass.

Though he towers above us, here God is surrounded by man—crazy men, to be exact. My family has five houses branching out in an L shape, anchored on the corner by the redbrick church. We are four houses of old-school Irish, the people who have raised me—McNicholases, O’Hagans, Farrells—and across the street, one lonely outpost of Italians, who peppered my upbringing. These are the Sorrentinos and the Zerillis, hailing from Sorrento, Italy, via Brooklyn via Ellis Island. Here dwell my mother’s mother, Adelina Rosa Zerilli; my mother’s older sister, Dora; Dora’s husband, Warren (an Irishman of course); and their daughter, my older cousin Margaret. Margaret and my cousin Frank are championship jitterbug dancers, winning contests and trophies up and down the Jersey Shore.

Though not unfriendly, the clans do not often cross the street to socialize with one another.

The house I live in with my grandparents is owned by my great-grandmother “Nana” McNicholas, my grandmother’s mother, alive and kicking just up the street. I’ve been told our town’s first church service and first funeral were held in our living room. We live here beneath the lingering eyes of my father’s older sister, my aunt Virginia, dead at five, killed by a truck while riding her tricycle past the corner gas station. Her portrait hovers, breathing a ghostly air into the room and shining her ill-fated destiny over our family gatherings.

Hers is a sepia-toned formal portrait of a little girl in an old-fashioned child’s white linen dress. Her seemingly benign gaze, in the light of events, now communicates, “Watch out! The world is a dangerous and unforgiving place that will knock your ass off your tricycle and into the dead black unknown and only these poor, misguided and unfortunate souls will miss you.” Her mother, my grandma, heard that message loud and clear. She spent two years in bed after her daughter’s death and sent my father, neglected, with rickets, off to the outskirts of town to live with other relatives while she recovered.

Time passed; my father quit school at sixteen, working as a floor boy in the Karagheusian Rug Mill, a clanging factory of looms and deafening machinery that stretched across both sides of Center Street in a part of town called “Texas.” At eighteen, he went to war, sailing on the Queen Mary out of New York City. He served as a truck driver at the Battle of the Bulge, saw what little of the world he was going to see and returned home. He played pool, very well, for money. He met and fell in love with my mother, promising that if she’d marry him, he’d get a real job (red flag!). He worked with his cousin, David “Dim” Cashion, on the line at the Ford Motor plant in Edison and I came along.

For my grandmother, I was the firstborn child of her only son and the first baby in the house since the death of her daughter. My birth returned to her a life of purpose. She seized on me with a vengeance. Her mission became my ultimate protection from the world within and without. Sadly, her blind single-minded devotion would lead to hard feelings with my father and enormous family confusion. It would drag all of us down.

When it rains, the moisture in the humid air blankets our town with the smell of damp coffee grounds wafting in from the Nescafé factory at the town’s eastern edge. I don’t like coffee but I like that smell. It’s comforting; it unites the town in a common sensory experience; it’s good industry, like the roaring rug mill that fills our ears, brings work and signals our town’s vitality. There is a place here—you can hear it, smell it—where people make lives, suffer pain, enjoy small pleasures, play baseball, die, make love, have kids, drink themselves drunk on spring nights and do their best to hold off the demons that seek to destroy us, our homes, our families, our town.

Here we live in the shadow of the steeple, where the holy rubber meets the road, all crookedly blessed in God’s mercy, in the heart-stopping, pants-dropping, race-riot-creating, oddball-hating, soul-shaking, love-and-fear-making, heartbreaking town of Freehold, New Jersey.

Let the service begin.

TWO

MY HOUSE

It’s Thursday night, trash night. We are fully mobilized and ready to go. We have gathered in my grandfather’s 1940s sedan waiting to be deployed to dig through every trash heap overflowing from the curbs of our town. First, we’re heading to Brinckerhoff Avenue; that’s where the money is and the trash is finest. We have come for your radios, any radios, no matter the condition. We will scavenge them from your junk pile, throw them into the trunk and bring them home to “the shed,” my grandfather’s six-by-six-foot unheated wooden cubicle in a tiny corner of our house. Here, winter and summer, magic occurs. Here in a “room” filled with electrical wire and filament tubes, I will sit studiously at his side. While he wires, solders and exchanges bad tubes for good, we wait together for the same moment: that instant when the whispering breath, the beautiful low static hum and warm sundown glow of electricity will come surging back into the dead skeletons of radios we have pulled from extinction.

Here at my grandfather’s workbench, the resurrection is real. The vacuum silence will be drawn up and filled with the distant, crackling voices of Sunday preachers, blabbering pitchmen, Big Band music, early rock ’n’ roll and serial dramas. It is the sound of the world outside straining to reach us, calling down into our little town and deeper, into our hermetically sealed universe here at 87 Randolph Street. Once returned to the living, all items will be sold for five dollars in the migrant camps that, come summer, will dot the farm fields on the edge of our borough. The “radio man” is coming. That’s how my grandfather is known amongst the mostly Southern black migrant population that returns by bus every season to harvest the crops of rural Monmouth County. Down the dirt farm roads to the shacks in the rear where dust-bowl thirties conditions live on, my mother drives my stroke-addled grandpa to do his business amongst “the blacks” in their “Mickey Mouse” camps. I went once and was frightened out of my wits, surrounded in the dusk by hard-worn black faces. Race relations, never great in Freehold, will explode ten years later into rioting and shootings, but for now, there is just a steady, uncomfortable quiet. I am simply the young protégé grandson of the “radio man,” here amongst his patrons where my family scrambles to make ends meet.

• • •

We were pretty near poor, though I never thought about it. We were clothed, fed and bedded. I had white and black friends worse off. My parents had jobs, my mother as a legal secretary and my father at Ford. Our house was old and soon to be noticeably decrepit. One kerosene stove in the living room was all we had to heat the whole place. Upstairs, where my family slept, you woke on winter mornings with your breath visible. One of my earliest childhood memories is the smell of kerosene and my grandfather standing there filling the spout in the rear of the stove. All of our cooking was done on a coal stove in the kitchen; as a child I’d shoot my water gun at its hot iron surface and watch the steam rise. We’d haul the ashes out the back door to the “ash heap.” Daily I’d return from playing in that pile of dust pale from gray coal ash. We had a small box refrigerator and one of the first televisions in town. In an earlier life, before I was born, my granddad had been the proprietor of Springsteen Brothers Electrical Shop. So when TV hit, it arrived at our house first. My mother told me neighbors from up and down the block would stop by to see the new miracle, to watch Milton Berle, Kate Smith and Your Hit Parade. To see wrestlers like Bruno Sammartino face off against Haystacks Calhoun. By the time I was six I knew every word to the Kate Smith anthem, “When the Moon Comes Over the Mountain.”

In this house, due to order of birth and circumstance, I was lord, king and the messiah all rolled into one. Because I was the first grandchild, my grandmother latched on to me to replace my dead aunt Virginia. Nothing was out of bounds. It was a terrible freedom for a young boy and I embraced it with everything I had. I stayed up until three a.m. and slept until three p.m. at five and six years old. I watched TV until it went off and I was left staring alone at the test pattern. I ate what and when I wanted. My parents and I became distant relatives and my mother, in her confusion and desire to keep the peace, ceded me to my grandmother’s total dominion. A timid little tyrant, I soon felt like the rules were for the rest of the world, at least until my dad came home. He would lord sullenly over the kitchen, a monarch dethroned by his own firstborn son at his mother’s insistence. Our ruin of a house and my own eccentricities and power at such a young age shamed and embarrassed me. I could see the rest of the world was running on a different clock and I was teased for my habits pretty thoroughly by my neighborhood pals. I loved my entitlement, but I knew it wasn’t right.

• • •

When I became of school age and had to conform to a time schedule, it sent me into an inner rage that lasted most of my school years. My mother knew we were all way overdue for a reckoning and, to her credit, tried to reclaim me. She moved us out of my grandmother’s house to a small, half-shotgun-style house at 391/2 Institute Street. No hot water, four tiny rooms, four blocks away from my grandparents. There she tried to set some normal boundaries. It was too late. Those four blocks might as well have been a million miles. I was roaring with anger and loss and every chance I got, I returned to stay with my grandparents. It was my true home and they felt like my real parents. I could and would not leave.

The house by now was functional only in one room, the living room. The rest of the house, abandoned and draped off, was falling down, with one wintry and windblown bathroom, the only place to relieve yourself, and no functioning bath. My grandparents fell into a state of poor hygiene and care that would shock and repel me now. I remember my grandmother’s soiled undergarments, just washed, hanging on the backyard line, frightening and embarrassing me, symbols of the inappropriate intimacies, physical and emotional, that made my grandparents’ home so confusing and compelling. But I loved them and that house. My grandma slept on a worn spring couch with me tucked in at her side while my grandfather had a small cot across the room. This was it. This was what it had come to, my childhood limitlessness. This was where I needed to be to feel at home, safe, loved.

The grinding hypnotic power of this ruined place and these people would never leave me. I visit it in my dreams today, returning over and over, wanting to go back. It was a place where I felt an ultimate security, full license and a horrible unforgettable boundary-less love. It ruined me and it made me. Ruined, in that for the rest of my life I would struggle to create boundaries for myself that would allow me a life of some normalcy in my relationships. It made me in the sense that it would set me off on a lifelong pursuit of a “singular” place of my own, giving me a raw hunger that drove me, hell-bent, in my music. It was a desperate, lifelong effort to rebuild, on embers of memory and longing, my temple of safety.

For my grandmother’s love, I abandoned my parents, my sister and much of the world itself. Then that world came crashing in. My grandparents became ill. The whole family moved in together again, to another half house, at 68 South Street. Soon, my younger sister, Pam, would be born, my grandfather would be dead and my grandmother would be filled with cancer. My house, my backyard, my tree, my dirt, my earth, my sanctuary would be condemned and the land sold, to be made into a parking lot for St. Rose of Lima Catholic church.

THREE

THE CHURCH

There was a circuit we could ride on our bikes that took us completely around the church and the rectory and back alongside the convent, rolling over the nuns’ beautiful, faded blue slate driveway. The slightly raised edges of the slate would send vibrations up through your handlebars, creating tiny pulsing rhythms in your hands, bump—ump—ump—ump . . . concrete, then back around we’d go again. Sleepy afternoons would pass with our winding in and out of the St. Rose compound, being scolded through the convent windows by the sisters to go home and dodging stray cats that wandered in between the church basement and my living room. My grandfather, now with nothing much to do, would spend his time patiently wooing these wild creatures to his side in our backyard. He could get near and pet feral cats that would have nothing to do with another human. Sometimes the price was steep. He came in one evening with a bloody foot-long scratch down his arm from a kitty that was not quite ready for the love.

The cats drifted back and forth from our house to the church just as we drifted to school, to home, to mass, to school again, our lives inextricably linked with the life of the church. At first the priests and nuns were just kind faces peering down into your carriage, all smiles and pleasant mystery, but come school age, I was inducted into the dark halls of communion. There was the incense, the men crucified, the torturously memorized dogma, the Friday Stations of the Cross (the schoolwork!), the black-robed men and women, the curtained confessional, the sliding window, the priest’s shadowy face and the recitation of childhood transgression. When I think about the hours I spent devising a list of acceptable sins I could spout on command . . . They had to be bad enough to be believable . . . but not too bad (the best was yet to come!). How much sinning could you actually have done at a second-grade level? Eventually, St. Rose of Lima’s Monday-through-Sunday holy reckoning would wear me out and make me want out . . . bad. But out to where? There is no out. I live here! We all do. All of my tribe. We are stranded on this desert island of a corner, bound together in the same boat. A boat that I have been instructed by my catechism teachers is at sea eternally, death and Judgment Day being just a divvying up of passengers as our ship sails through one metaphysical lock to another, adrift in holy confusion.

And so . . . I build my other world. It is a world of childhood resistance, a world of passive refusal from within, my defense against “the system.” It is a refusal of a world where I am not recognized, by my grandmother’s lights and mine, for who I am, a lost boy king, forcibly exiled daily from his empire of rooms. My grandma’s house! To these schmucks, I’m just another spoiled kid who will not conform to what we all ultimately must conform to, the only-circumstantially-theistic kingdom of . . . THE WAY THINGS ARE! The problem is I don’t know shit, nor care, about “the way things are.” I hail from the exotic land of . . . THINGS THE WAY I LIKE ’EM. It’s just up the street. Let’s all call it a day and just go HOME!

No matter how much I want to, no matter how hard I try, “the way things are” eludes me. I desperately want to fit in but the world I have created with the unwarranted freedom from my grandparents has turned me into an unintentional rebel, an outcast weirdo misfit sissy boy. I am alienating, alienated and socially homeless . . . I am seven years old.

Amongst my male classmates, there are mainly good souls. Some, however, are rude, predatory and unkind. It is here I receive the bullying all aspiring rock stars must undergo and suffer in seething, raw, humiliating silence, the great “leaning up against the chain-link fence as the world spins around you, without you, in rejection of you” playground loneliness that is essential fuel for the coming fire. Soon, all of this will burn and the world will be turned upside down on its ass . . . but not yet.

The girls, on the other hand, shocked to find what appears to be a shy, softhearted dreamer in their midst, move right onto Grandma’s turf and begin to take care of me. I build a small harem who tie my shoes, zip my jacket, shower me with attention. This is something all Italian mama’s boys know how to do well. Here your rejection by the boys is a badge of sensitivity and can be played like a coveted ace for the perks of young geekdom. Of course, a few years later, when sex rears its head, I’ll lose my exalted status and become just another mild-mannered loser.

The priests and nuns themselves are creatures of great authority and unknowable sexual mystery. As both my flesh-and-blood neighbors and our local bridge to the next life, they exert a hard influence over our daily existence. Both everyday and otherworldly, they are the neighborhood gatekeepers of a dark and beatific world I fear and desire entrance to. It’s a world where all you have is at risk, a world filled with the unknown bliss of resurrection, eternity and the unending fires of perdition, of exciting, sexually tinged torture, immaculate conceptions and miracles. A world where men turn into gods a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Book One: Growin’ Up

- Book Two: Born To Run

- Book Three: Living Proof

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- Photo Credits

- About the Author

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.