eBook - ePub

Dreamers and Deceivers

True Stories of the Heroes and Villains Who Made America

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

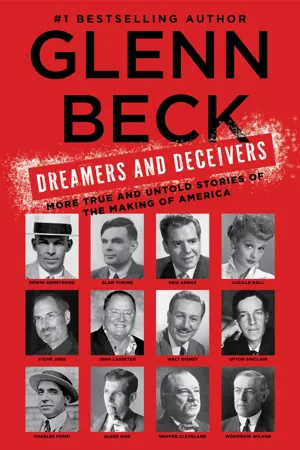

From Glenn Beck, the New York Times bestselling author of The Great Reset, comes the powerful follow-up to his national bestseller Miracles and Massacres, which was praised as “moving, provocative, and masterful” (Michelle Malkin, bestselling author of Culture of Corruption).

Everyone has heard of a “Ponzi scheme,” but do you know what Charles Ponzi actually did to make his name synonymous with fraud? You’ve probably been to a Disney theme park, but did you know that the park Walt believed would change the world was actually EPCOT? He died before his vision for it could ever be realized. History is about so much more than dates and dead guys; it’s the greatest story ever told. Now, in Dreamers and Deceivers, Glenn Beck brings ten more true and untold stories to life.

The people who made America were not always what they seemed. There were entrepreneurs and visionaries whose selflessness propelled us forward, but there were also charlatans and fraudsters whose selfishness nearly derailed us. Dreamers and Deceivers brings both of these groups to life with stories written to put you right in the middle of the action.

From the spy Alger Hiss, to the visionary Steve Jobs, to the code-breaker Alan Turing—once you know the full stories behind the half-truths you’ve been force fed…once you begin to see these amazing people from our past as people rather than just names—your perspective on today’s important issues may forever change.

Everyone has heard of a “Ponzi scheme,” but do you know what Charles Ponzi actually did to make his name synonymous with fraud? You’ve probably been to a Disney theme park, but did you know that the park Walt believed would change the world was actually EPCOT? He died before his vision for it could ever be realized. History is about so much more than dates and dead guys; it’s the greatest story ever told. Now, in Dreamers and Deceivers, Glenn Beck brings ten more true and untold stories to life.

The people who made America were not always what they seemed. There were entrepreneurs and visionaries whose selflessness propelled us forward, but there were also charlatans and fraudsters whose selfishness nearly derailed us. Dreamers and Deceivers brings both of these groups to life with stories written to put you right in the middle of the action.

From the spy Alger Hiss, to the visionary Steve Jobs, to the code-breaker Alan Turing—once you know the full stories behind the half-truths you’ve been force fed…once you begin to see these amazing people from our past as people rather than just names—your perspective on today’s important issues may forever change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dreamers and Deceivers by Glenn Beck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Grover Cleveland: The Mysterious Case of the Disappearing President

Albany, New York

July 21, 1884

Governor Grover Cleveland stared in disbelief at the front page of the Buffalo Telegraph. Just ten days earlier he had received the Democratic Party’s nomination for president, and given his reputation for unwavering honesty, he knew that he had a real chance to win. His Republican opponent, the notoriously corrupt James G. Blaine—a man who would soon become known as “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the Continental liar from the state of Maine!”—was vulnerable. If Cleveland managed to parlay his sterling reputation into a victory in November, he would be the first Democrat elected since before the Civil War.

But now, as Cleveland stared in disgust at the newspaper sitting on his desk, victory looked a lot less likely. A TERRIBLE TALE, screamed the morning’s headline. A DARK CHAPTER IN A PUBLIC MAN’S HISTORY.

The Telegraph’s article told the story of Maria Halpin, a widow in Cleveland’s hometown of Buffalo, who had a child named Oscar Folsom Cleveland.

Cleveland, a bachelor, had never acknowledged that his former lover’s child was his. After all, several of his drinking buddies had also shared Maria’s bed—could he really be sure of his paternity? But those friends were all married, so Cleveland had agreed to give the child his last name and his financial support. When the boy was sent to an orphanage after Maria’s excessive drinking and deteriorating emotional state led to her stay in a mental institution, Cleveland had dutifully paid the orphanage bill of five dollars a week.

Now, in the midst of Cleveland’s presidential campaign, the nine-year-old child’s very existence threatened to derail his White House hopes—unless he could find a way to turn this crisis into an opportunity.

As Cleveland read through the article, much of which was exaggerated and sensationalized, the governor began to formulate a strategy. The American people, he reasoned, would forgive a sexual indiscretion. In fact, if he was completely honest about something so embarrassing—something so many men lied about almost out of habit—voters might actually reward him. His candor would reinforce the trustworthiness that had been his calling card ever since he’d been elected to replace Buffalo’s corrupt mayor in 1881 and New York’s corrupt governor in 1882. Now, in a meteoric rise to national prominence, that same forthrightness would save his nomination for president of the United States.

“Write this down, and send it to all my friends in Buffalo,” Cleveland ordered his press secretary and close confidant, Daniel Lamont. “I have a simple message for anyone who is asking anything about Maria Halpin.” His voice now boomed with confidence and authority. “Whatever you do . . . tell the truth!”

• • •

Cleveland’s strategy worked perfectly. By the narrowest of margins, and, in large part thanks to the trust inspired by his response to the Maria Halpin scandal, the governor of New York was elected president of the United States of America. Joseph Pulitzer, of the New York World, spoke for millions when he explained the four reasons he supported Grover Cleveland: “1. He is an honest man; 2. He is an honest man; 3. He is an honest man; 4. He is an honest man.”

Nine Years Later

From Washington, D.C., to New York City

July 1, 1893

The president grimaced as he climbed into the presidential carriage for the trip down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Baltimore & Potomac train station. It took quite an effort for the six-foot, one-inch, three-hundred-pound chief executive to get from the ground to his seat. Even though Grover Cleveland was more than strong enough, the fifty-six-year-old didn’t enjoy physical exertion. He’d once told Daniel Lamont, who was now serving as secretary of war, that even walking was an annoyance to be avoided whenever possible.

Lamont was at Cleveland’s side for the ride to the train station, just as he had been for the better part of the last decade. The president thought of his friend, who was fourteen years younger, as the son he’d never had. Lamont even looked in some ways like a slightly thinner and balder version of Cleveland, right down to the bushy walrus mustache they both sported. Unfailingly loyal, Lamont and Cleveland shared an affinity for whiskey, cigars, hunting, and fishing.

Lamont was by Cleveland’s side when he won the presidential election in 1884, and he was there when Cleveland lost the White House in 1888, despite having won the popular vote. Four years later, Lamont reprised his role as press secretary in Cleveland’s bid to reclaim the presidency. They celebrated together in 1892 when Cleveland defeated Benjamin Harrison by a landslide.

In his second term Cleveland promoted his friend to secretary of war, but the president continued to rely on Lamont’s judgment and counsel in all critical matters of state. First among those matters was the “money question.”

The Silver Purchase Act of 1890 required the United States Treasury to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver each month and to print large amounts of paper currency that could be redeemed for that silver. The consequence was inflation—wild, catastrophic, panic-inducing inflation. By Cleveland’s inauguration in March, the United States was in the midst of the worst economic recession in its history: the aptly labeled Panic of 1893.

Cleveland and Lamont arrived at the train station and boarded a special car prepared for them by the railroad’s owner. The president placed a supremely high value on discretion. Once aboard, his first priority was to order a cigar and a whiskey. His second order of business was to pull down the window shades. A private man even under ordinary circumstances, Cleveland knew the purpose of this trip was anything but ordinary. The press and public were on a “need to know” basis, and as far as he was concerned, there was nothing about this journey that any of them needed to know.

Cleveland had frequently received good press, especially as it related to his anticorruption efforts as mayor, governor, and president, yet he still despised reporters. As the train left the station, he recalled all the times journalists had poked their noses in where they didn’t belong, beginning with their coverage of the Maria Halpin affair.

At times, Cleveland’s rage at reporters turned to fits of anger. At other times, he found an outlet for his frustration by writing blistering letters to newspaper editors. To one publication, he wrote that “the falsehoods daily spread before the people in our newspapers are insults to the American love for decency and fair play of which we boast.” To another, he blasted “keyhole correspondents” for using “the enormous power of the modern newspaper to perpetuate and disseminate a colossal impertinence.”

The whiskey soon arrived, as did the cigar. With all the shades pulled down, Cleveland was able to relax for the first time since he’d hoisted himself into the presidential carriage. Only after he and Lamont were safely away from the Washington, D.C., area did Cleveland raise the shades to enjoy the views as the New York Express chugged northward.

The sights outside the president’s window, however, were not always pleasing to his eye. Occasionally the train would pass by shantytowns filled with jobless vagabonds and homeless families making the most of what tin, cardboard, and spare lumber they could find to create shelter.

The train was moving fast, but he could still see the misery in the sunken eyes of the unfortunate inhabitants. Cleveland knew that unemployment was at an all-time high, that stocks were anemic, that banks, railroads, and factories were failing, that farm foreclosures were rampant, and that all the wrong rates were rising: interest rates, unemployment rates, and, if the papers were to be believed, suicide rates as well. Even so, Cleveland was not prepared for the wretched, impoverished conditions he saw from his window. The shantytowns looked like refugee camps in some third-world, war-ravaged country.

The tragic sights of suffering steeled the president’s resolve to repeal the Silver Purchase Act. Just that morning, before surreptitiously leaving the capital, he had called for a special session of Congress to consider repealing the law he blamed for the country’s woes. He was sure he could persuade them to eliminate the act. He was coming off a landslide election and the political momentum was squarely on his side. Only public disclosure of the purpose of the trip he was now on could stop him.

Cleveland arrived in Jersey City, New Jersey, and boarded a ferry for Manhattan. His destination was a luxurious yacht anchored in the East River, which would then sail him to his vacation home in Massachusetts, on Buzzards Bay, off Cape Cod. Before he could get there, however, he had to deal with a handful of reporters who had discovered that the president was no longer at the White House. They were curious to know why he had left Washington on the eve of debate over the Silver Purchase Act.

“I have nothing to say for publication, except that I am going to Buzzards Bay for a rest.”

New York City

July 1, 1893

Early Evening

Among the reporters who had been on the ferry with Grover Cleveland was Elisha Jay Edwards, known to readers of his almost daily column by his one-word penname: Holland.

With a thick, light brown mustache that did little to obscure his handsome, angular face, Edwards was among the most diligent and respected journalists in the nation. A skilled researcher and writer, he had graduated from Yale Law School in 1873 and then stayed in New Haven to practice law. Those plans changed when he purchased an interest in New Haven’s Elm City Press. Before long, his photographic memory, penchant for dogged investigations, and ability to write quickly, clearly, and elegantly made him the best reporter in that Connecticut city.

The early 1870s were the beginning of a drastic, two-decade media expansion. New printing technologies and a rise in literacy were the driving forces behind a threefold increase in newspaper sales. During that era, no publisher was as respected and feared as the New York Sun’s Charles Dana. It was Dana who plucked the talented Edwards out of obscurity and brought him from New Haven to New York in 1879.

After ten years of twelve-hour days with Dana, Edwards took a job as the New York correspondent for the Philadelphia Press. It was there that “Holland” became one of the most read syndicated columnists in the country.

Six days a week, in newsrooms across the nation, reporters would begin their day by asking the same question: “What does Holland say today?”

As the evening sun set outside his window in the Schermerhorn Building on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Edwards wrote out the next day’s column in longhand. It included a bit of gossip about Interior Secretary Hoke Smith, “the only member of the cabinet who has dared to assert himself in the presence of the president,” and a little news about “a delegation of starving miners” who “may be sent to Washington from Colorado and Montana demanding from President Cleveland not bread but silver, which is the same to them.” Finally, near the end of the column, was a note about how President Cleveland and his friend Elias Benedict were planning to spend much of July together at their vacation homes on Buzzards Bay. “Mr. Benedict says that Mr. Cleveland is as impatient for the sea bass fishing and as hungry for a day’s sport trolling for bluefish as a schoolboy is for the first day of his vacation.”

On Board the Oneida

East River, New York City

July 2, 1893

10:30 A.M.

As the Oneida pulled anchor on a warm, sunny morning and set sail northward, the president of the United States smiled and relaxed comfortably on her deck. He always felt his best when surrounded by old friends, and he had plenty of them now lounging beside him: his friend Elias Benedict, Lamont, and Joseph Bryant, who was his brother-in-law, family doctor, and frequent fishing companion. Over the years, Cleveland had traveled more than fifty thousand miles on the Oneida, often with some combination of these three men at his side and a fishing pole in his hand.

Cleveland’s affinity for the boat was understandable, perhaps even unavoidable. With two masts and a glistening white 144-foot hull, she was a sleek, spectacularly gorgeous yacht. In 1885, the vessel—then named the Utowana—won the prestigious Lunberg Cup race. Soon after that, Elias Benedict purchased it and rechristened her Oneida.

The p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Author’s Note

- 1. Grover Cleveland: The Mysterious Case of the Disappearing President

- 2. “I Did Not Kill Armstrong”: The War of Wills in the Early Days of Radio

- 3. Woodrow Wilson: A Masterful Stroke of Deception

- 4. Streets of Gold: Charles Ponzi and the American Scheme

- 5. He Loved Lucy: The Tragic Genius of Desi Arnaz, the Inventor of the Rerun

- 6. The Muckraker: How a Lost Letter Revealed Upton Sinclair’s Deception

- 7. Alan Turing: How the Father of the Computer Saved the World for Democracy

- 8. The Spy Who Turned to a Pumpkin: Alger Hiss and the Liberal Establishment That Defended a Traitor

- 9. The City of Tomorrow: Walt Disney’s Last and Lost Dream

- 10. “Make It Great, John”: How Steve Jobs and John Lasseter Changed History at Pixar

- Appendix: Letter from Upton Sinclair

- About Glenn Beck

- About the Writing of This Book

- Copyright