- 50 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

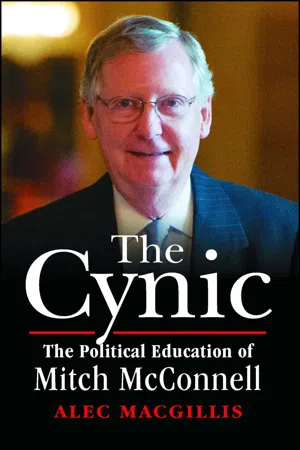

From a dogged political reporter, an investigation into the political education of Mitch McConnell and an argument that this powerful Senator embodies much of this country’s political dysfunction.

Based on interviews with more than seventy-five people who have worked alongside Mitch McConnell or otherwise interacted with him over the course of his career, The Cynic, which will be published as an original ebook, is both a comprehensive biography of one of this country’s most powerful politicians and a damning diagnosis of this country's eroding political will.

Tracing his rise from a pragmatic local official in Kentucky to the leader of the Republican opposition in Washington, the book tracks McConnell’s transformation from a moderate Republican who supported abortion rights and public employee unions to the embodiment of partisan obstructionism and conservative orthodoxy on Capitol Hill. Driven less by a shift in ideological conviction than by a desire to win elections and stay in power at all costs, McConnell’s transformation exemplifies the “permanent campaign” mindset that has come to dominate American government.

From his first race for local office in 1977—when the ad crew working on it nicknamed McConnell “love-me-love-me” for his insecurity and desire to please—to his fraught accommodation of the Tea Party, McConnell’s political career is a story of ideological calcification and a vital mirror for understanding this country’s own political development and what is wrought when politicians serve not at the behest of country, but at the behest of party and personal aggrandizement.

Based on interviews with more than seventy-five people who have worked alongside Mitch McConnell or otherwise interacted with him over the course of his career, The Cynic, which will be published as an original ebook, is both a comprehensive biography of one of this country’s most powerful politicians and a damning diagnosis of this country's eroding political will.

Tracing his rise from a pragmatic local official in Kentucky to the leader of the Republican opposition in Washington, the book tracks McConnell’s transformation from a moderate Republican who supported abortion rights and public employee unions to the embodiment of partisan obstructionism and conservative orthodoxy on Capitol Hill. Driven less by a shift in ideological conviction than by a desire to win elections and stay in power at all costs, McConnell’s transformation exemplifies the “permanent campaign” mindset that has come to dominate American government.

From his first race for local office in 1977—when the ad crew working on it nicknamed McConnell “love-me-love-me” for his insecurity and desire to please—to his fraught accommodation of the Tea Party, McConnell’s political career is a story of ideological calcification and a vital mirror for understanding this country’s own political development and what is wrought when politicians serve not at the behest of country, but at the behest of party and personal aggrandizement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cynic by Alec MacGillis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter Three

FOLLOW THE LEADER

Bob Graham, the idiosyncratic Florida Democrat perhaps best remembered for keeping minutely detailed daily journals, joined the Senate in 1987, just two years after Mitch McConnell. Yet so much did McConnell keep to himself, and to his own party, that Graham had barely gotten to know his colleague from Kentucky—until, that is, they both had heart surgery within three days in early 2003 at Bethesda Naval Hospital.

McConnell had gone for a stress test recommended by the Capitol physician, and had failed it, leading to cardiac catheterization and instructions to undergo triple bypass surgery, pronto. Graham was there to have nonemergency surgery on his aortic heart valve. And in the week of convalescence that followed, they became postsurgical kindred spirits. Day after day, they walked up and down the hallways together to regain their strength. And they spent a lot of time talking, about, as Graham recalls it, “our families, what had brought us into politics, what we hoped to accomplish in politics.”

Somewhat to his surprise, Graham liked his fellow patient. “I developed a very warm feeling toward Mitch,” he says. “Mitch is by nature a little aloof—he doesn’t have what some in politics have, that natural affinity and warmth for people. When I got to know him, I found him to be a more open and sympathetic and friendly person than under previous circumstances.”

Yet that week away from the Sturm und Drang on Capitol Hill was not transformative in the broader sense. Both senators returned to a Senate more riven with every month. The upper chamber of the legislature had long prided itself on being less defined by partisan markers than the House of Representatives. The smaller size of the Senate gave it a clubby solidarity that the House lacked, its members served for longer terms and typically longer tenures than their counterparts in the House, giving them more time to get to know each other. They also represented entire states, encouraging a broadness of perspective that a House member representing a narrowly defined district might be less likely to have.

That singularity had been fading for some time, though. The parties had been sorting themselves out geographically and ideologically. One was far less likely than three decades prior to encounter a Northern liberal Republican senator or a conservative Southern Democrat. The increased cost of campaigning meant more time spent fund-raising and catering to party leaders or deep-pocketed funders who did not look so kindly on cross-aisle forays. Cable news had not helped matters. And the growing hegemony of the thirty-second ad as the ultimate campaign weapon had spurred senators to offer irrelevant amendments on bills to force the opposition to cast votes on hot-button issues that could be construed in unflattering ways in an eventual negative ad.

The evolution of the chamber could be traced in institutional increments, notably to the rise in the use of the filibuster—which in the past had been resorted to almost exclusively for the rare historic conflict, as on civil rights legislation—to stall or block routine legislation and nominations, to the point where it became necessary to have sixty votes to accomplish even the most rudimentary business. And it could be traced in episodes where the breakdown in comity was on display, from the judicial confirmation hearings for Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas to the ads run in 2002 against Georgia Democrat Max Cleland, a triple-amputee Vietnam War veteran, by his Republican challenger, Saxby Chambliss, that linked Cleland to images of Osama bin Laden and declared Cleland did not have the “courage to lead” because he voted against Republicans on the structure of the new Department of Homeland Security. Chambliss won Cleland’s seat, only heightening the partisan ill will in the chamber to which McConnell and Graham returned after their bipartisan recuperation in January 2003.

And it would get much worse. In 2007, after Democrats reclaimed majorities in both chambers in 2006 and Mitch McConnell ascended to become his party’s leader in the Senate, the use of the filibuster soared—when Democrats were in the Senate minority during the Reagan years and George W. Bush years, there were, respectively, about 40 and 60 “cloture motions” to break or preempt filibusters filed per session, one commonly used measure of obstructionism. With the Republicans back in the minority in 2007 under McConnell’s leadership, cloture motions spiked to 140 per session. By 2009, when the Democrats gained back the White House, the use of the filibuster spread, far more than ever before, to block presidential nominees of even the most pedestrian offices. “The idea of a filibuster as the expression of a minority that felt so intensely that it would pull out all the stops to block something pushed by the majority went by the boards,” wrote Ornstein, the congressional scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, in 2014. “This was a pure tactic of obstruction, trying to use up as much of the Senate’s most precious commodity—time—as possible to screw up the majority’s agenda.”

By 2011, the Senate and the rest of the gridlocked government found themselves on the brink of a national credit default, a brink reached again in another partisan standoff two years later, with the added bonus of a two-week-long shutdown of the federal government.

Bob Graham left the Senate in 2005, two years before McConnell took the helm of the Republican caucus. And from the vantage of southern Florida, Graham struggled to understand why the veteran senator whose company he had enjoyed in the hospital hallways had allowed Senate politics to come to this pass—in particular, why he had allowed the ideological wing of his caucus, a camp with so little regard for custom and comity that it often bordered on the gleefully nihilistic, to acquire such sway in Washington. Graham remembered other Republican leaders he had served alongside, and found it hard to believe they wouldn’t have responded differently.

“I don’t think that if the leader were of the ilk of a Bob Dole, if he had a sense of history and used history as a guide, that it would have happened like this,” Graham says. “I don’t know why they have fallen into what may bring short-term gains and maybe even some pleasure, but which maybe on a longer view of history is going to be very damning. . . . He is accommodating his hottest members, and they have not demonstrated any responsibility to the future or to how their actions are going to be seen in that long procession of time. I guess Mitch has made a decision that this wasn’t a battle that he was going to take on.”

The only thing Mitch McConnell wanted as much as winning elections for the Senate was winning elections within the Senate. Let other senators dream of running for president. For him, the dream was running the institution he had been revering since he was a boy. In this ambition, he was following the example of countless Southern politicians who had made the Senate their home in decades past, capitalizing on their own longevity in safe seats and the Senate’s seniority system to dominate the institution well into the twentieth century. The Senate, wrote veteran New York Times congressional correspondent William S. White in the mid-1950s, was “peculiarly Southern both in flavor and structure,” so much so that it had become, essentially, “the South’s unending revenge . . . for Gettysburg.” With its very Southern emphasis on courtliness and decorum—all those rules that “imposed a verbal impersonality on debate to ensure civility and formality,” as LBJ biographer Robert Caro puts it—the Senate was the one political venue where McConnell’s detached manner was not only not a hindrance, it was an asset. Here, formality conveyed authority, not discomfort.

Where other aspiring politicians steeped themselves in the legends of the White House, McConnell had immersed himself in the lore of the legislative branch’s upper chamber. “He’s a great student of the institution,” says Dave Schiappa, who until 2013 served as McConnell’s chief aide on the Senate floor. “He loves the history, loves to read everything he can get his hands on.” This study wasn’t just sentimental; it was geared toward learning the precedents and procedures that governed the chamber, a command that had helped McConnell’s Southern forebears gain control over the institution. The lords of the Senate were his idols, and he wanted to be counted among them: “He’s made a whole career of being the master of [the] Senate—the Republican version of LBJ, without the physical attributes,” says Al Cross, a longtime political reporter with the Courier-Journal who now works at the University of Kentucky.

Partly, the drive to be majority leader was just a matter of ticking off the top item on the checklist. “There are things that he wants to accomplish in his career—while he’s been majority whip, he’s never been majority leader, and that’s something he wants to have on his resume,” says Lula Davis, a former chief aide to Harry Reid, the Democratic Senate leader. But one former Senate caucus leader notes that it goes deeper than that. Leadership in the chamber comes with its own kind of power high, one that seems to have held an especially strong allure for introverts like McConnell and his eventual counterpart, Reid. “The intensity, the extraordinary rush to be in those positions, it’s addictive,” the former caucus leader said. “It’s the extraordinary exhilaration that comes with having these positions. . . . The intensity is almost like a drug.”

McConnell had tried twice for the job of National Republican Senatorial Committee chairman, losing both times to Phil Gramm of Texas, before getting the post in 1997. As successful as he was at fund-raising and as much goodwill as he’d earned from his colleagues for leading the fight against campaign finance reform, his record at the helm of the campaign committee was mixed. In 1998, the Senate balance remained unchanged despite Democrats having to defend more seats, and in 2000 the Democrats gained a net total of four seats. In 2001, the Senate Republican caucus voted to replace him with Bill Frist, of Tennessee.

This setback did not dissuade McConnell from continuing his climb. He set about lining up votes for the next election for majority whip, the second-ranking spot in leadership. He had in his favor the gratitude for his stand against McCain-Feingold, and his performance in the 1995 sexual harassment investigation of fellow Republican Bob Packwood, of Oregon. In the role of Ethics Committee chairman, McConnell had come down hard on Packwood while taking the heat from Democrats for not making the investigation more transparent. Working against his ascension, though, was the fact that plenty of Republicans had not warmed to their tightly wound Kentucky colleague. Sure, there were occasional flashes of a dry, almost English sense of humor. That said, McConnell was, as his former chief of staff observed to the Atlantic in 2011, “the least personal politician I’ve ever been around.”

But McConnell had a wingman. Bob Bennett, the towering senator from Utah who had stood almost alone with McConnell in opposing the anti-flag-burning amendment in 1995, would head out into the Republican caucus, one by one, feeling out senators about whether they might be inclined to support his friend over Larry Craig of Idaho, the other aspirant for the spot, who had not yet seen his career ended by a flirtatious encounter with an undercover male policeman in a bathroom at the Minneapolis airport. “He would go through every Republican in the Senate and say, ‘This one doesn’t like me,’ ‘You go see this one, I’ve talked to him as far as I can go, if I push any further I’ll push him over, you go see him,’ ” says Bennett. “He knew every single one of them.”

The wingman would head out. “I would size up the opposition. Many times it was ‘I really don’t like Mitch that much, but I really don’t like Larry.’ You had to be careful—you can’t be blatant about it. You go up and say, ‘There’s a leadership fight coming up, how do you feel between the two of them?’ ‘Well, you know, Mitch has his strengths,’ and then you get them talking about Mitch’s strengths. . . . Then I get the things he doesn’t like about Mitch. Pretty soon I get the sense of how he feels about Mitch. I go back and say, ‘He didn’t like what you did here, you need to have a conversation about this, you need to do that.’ So when Mitch would go see him, he was fore-armed with the intelligence I’d given him: ‘Senator, you probably don’t like what I did on such and such, I owe you an explanation on that.’ So the door opened and Mitch would come back and say, ‘Okay, we got him.’ ” When necessary, Bennett would try to undermine the opposition—subtly, of course. For instance, Bennett says, “John Warner [the former senator from Virginia] would say, ‘It’s far too early, I don’t want to discuss it,’ and I’d say, ‘Okay, that’s not a no,’ and I’d keep at it: ‘John, did you hear this [about Craig]?’ and he’d say, ‘I didn’t like that.’ ” To which Bennett would respond, “ ‘Well, there’s always Mitch. . . .’ ”

McConnell and Bennett started this process with a year and a half to go before the vote would be held, a lesson McConnell told Bennett he had learned from Bob Livingston, the Louisiana congressman who had lined up all the support he needed to become House Speaker long before Newt Gingrich stepped down. “McConnell said, ‘Livingston didn’t get the speakership because he was the best candidate—he got it because he was the first.’ ” The early start paid off. By the time the summer of 2002 rolled around with the leadership elections looming later that year, McConnell sat down with Craig and presented him with a list of all the commitments he’d gotten. “Mitch was elected whip unanimously and Larry Craig decided he was going to do something else, because Mitch had it all lined up,” Bennett says.

Soon afterward, McConnell and Bennett started using the same tactics to ready a run for the final rung, Republican leader—which at that point, in 2005, was also majority leader. They were well aware that Bill Frist had imposed a two-term limit on himself and would be gone after 2006—more aware than anyone else, says Bennett. “I don’t think anyone else was thinking about what to do when Bill Frist leaves. Well, Mitch was thinking the first day Frist was chosen [as leader in 2002], what do we do when Frist leaves. We were talking about it. He knew exactly what he had to say to each senator, what he had to do to neutralize the ones opposed to him.”

This calculus was rooted in McConnell’s acute political instincts. Even if he wasn’t close to that many of his colleagues, he knew where they were coming from, what they worried about, what they needed. “He knows what people are going to do long before they themselves see it,” says Judd Gregg, the former Republican senator from New Hampshire. On Election Night in 2004, when Lincoln Chafee—whose father had stood with McConnell and Bennett in opposing the flag-burning amendment—saw George W. Bush holding on for a second term, it occurred to him that his reelection campaign in 2006 as a Republican in Rhode Island was going to be a whole lot tougher with Bush, who’d lost Chafee’s state by 20 points, still in the White House.

The next day, McConnell called his liberal colleague to reassure him about his prospects two years hence—and to make sure he wasn’t toying with switching parties, as his fellow liberal New Englander James Jeffords of Vermont had done three years earlier. “I was considering options—do I change parties, what do I do here, and he called me right away and said, ‘Linc, I know what you’re thinking. We want you to stay a Republican.’ He was a mind reader that way. We all know you’re going to have a rough race, and we’ll get you the money we need.’ ” And they did. Asked by McConnell what sort of assistance he could use in Rhode Island, Chafee mentioned the hulking old bridge from the mainland to Jamestown, which the cash-strapped state had been meaning to take down for a dozen years. It cost $15 million. McConnell “immediately got it for me,” and the bridge was detonated at last. There was a road project in Warwick that had run out of money, which required another $9 million. McConnell got that, too. It irked many in the party, going to such lengths for a Republican who had voted against Bush’s tax cuts, the invasion of Iraq, and Supreme Court nominee Samuel Alito, and had even refused to support Bush’s reelection in 2004. “There are many that would rather just purge the party, but he knew it was all about the math—he was going to need a Republican to keep the majority,” Chafee says.

So determined was McConnell to hold the Senate majority in 2006, regardless of the cost, that in September of that year, with polls looking bleak for Republicans, he sought out Bush in a private meeting in the Oval Office to ask him to withdraw troops from Iraq to improve the party’s chances in that fall’s midterm election. Publicly, McConnell had been staunchly defending the war, but according to Bush, McConnell was so focused on the coming election cycle that he was willing to challenge Bush on the primary mission of his presidency. As Bush recounts in his memoir, McConnell told him, “Mr. President, your unpopularity is going to cost us control of the Congress.” Bush said he responded: “Well, Mitch, what do you want me to do about it?” McConnell, in Bush’s account, answered: “Mr. President, bring some troops home from Iraq.” Bush’s answer, as he recalls: “Mitch, I believe our presence in Iraq is necessary to protect America, and I will not withdraw troops unless military conditions warrant.” He would, he told McConnell, “set troop levels to achieve victory in Iraq, not victory at the polls.”

In the end, though, it was to no avail. Chafee lost his reelection, one of six incumbent Republican senators to lose that fall, giving the Democrats control of the chamber by a single vote. With his and Bennett’s groundwork laid, McConnell would be elected Republican leader, but not majority leader.

And as diligent as his pursuit of his party’s top spot had been, the effort required to attain it suggested that he would be able to rely less on sheer collegial affection to feel secure in his place than some of his predecessors had. It was a vulnerability that, if felt keenly enough, would have implications for managing the burgeoning right wing of his caucus, whose loyalties would come at a cost far greater than scattered millions for an old rusting bridge.

There was a taut silence in the room that day in the summer of 2007 as the Senate Republican caucus absorbed what their leader had just said. Mitch McConnell had assembled the caucus behind closed doors to address a major setback, the passage of a sweeping ethics reform package with barely any input from Republicans. The Senate had passed an ethics bill that did contain plenty of points of agreement between McConnell and Harry Reid, the new majority leader, but that bill had never made it to a conference committee, where it could be melded with the version passed by the House. The reason? Jim DeMint, the first-term, hard-right Republican from South Carolina, had placed a hold on the appointment of conferees, claiming that he could not trust the committee not to water down provisions he had gotten into the Senate bill requiring much greater transparency for earmarks. So House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Reid had figured out a way to pass a bill on their own, based primarily on the House version, and written to the liking of the Democrats.

Without naming DeMint, McConnell alluded to the hold and faulted it for leaving the Republicans in the lurch. It was an opaque allusion, but not so opaque that many members did not realize that McConnell had just called out DeMint in front of his colleagues. DeMint flared up and denied that he had forced the bad result, recalls Bob Bennett.

In a quiet but “very cold” voice, McConnell replied to the effect of: Yes. Yes, you did.

That’s not fair, protested DeMint.

No, Jim. You’re the one who did this, McConnell continued. You’re responsible for this outcome. . . . We did this to ourselves.

There had never been anything like it. “It was the only time I have ever seen Mitch McConnell deal with a colleague in that kind of manner,” Bennett says. “It was just a single sentence, but it left the whole room in stone-cold silence, because it was, ‘All right, this is a rebuke that really matters.’ ”

The confrontation helped cement the rivalry between McConnell and the South Carolinian who had arrived in the Senate in 2005 burning to take on not only Democrats but Republicans complicit in deficit-widening travesties such as the Medicare drug benefit supported by McConnell and signed by President Bush. DeMint was at the helm of a small but vocal group of senators who interpreted their party’s loss of the Senate as punishment for the party’s drift from budget-cutting orthodoxy. They had little patience for institutional niceties, among them deference to leadership.

What was most notable about the confrontation, though, was what Bennett stressed in recounting it—its singularity. McConnell was willing to give DeMint opaque reprimands behind closed doors on matters of institutional prerogative—senators’ right to award earmarks, or relying on seniority in making assignments to the influential Appropriations Committee, another issue where McConnell resisted DeMint. (“Jim, you can’t change the Senate,” he chided, according to DeMint.)

But when it came to the big issues, what McConnell would project to the public was the spectacle of a leader submitting to the gravitational pull of DeMint and the wing of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- A Note on Sources

- Preface

- One: Run, Run, Run

- Two: No Money Down

- Three: Follow the Leader

- Coda: Victory

- About the Author

- Copyright