- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

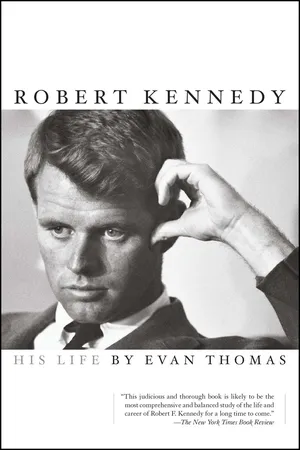

He was "Good Bobby," who, as his brother Ted eulogized him, "saw wrong and tried to right it . . . saw suffering and tried to heal it." And "Bad Bobby," the ruthless and manipulative bully of countless conspiracy theories. Thomas's unvarnished but sympathetic and fair-minded portrayal is packed with new details about Kennedy's early life and his behind-the-scenes machinations, including new revelations about the 1960 and 1968 presidential campaigns, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and his long struggles with J. Edgar Hoover and Lyndon Johnson.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Robert Kennedy by Evan Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Biografie in ambito storico. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 RUNT

FOR ALL HIS DESIRE to shape and promote his children, Joseph P. Kennedy does not seem to have paid much attention to the schooling of his third son and seventh child. In September 1939, Kennedy Sr. enrolled thirteen-year-old Robert at St. Paul’s School, an establishment training ground, but within a month RFK was gone. St. Paul’s was too Protestant for his mother, Rose. In early October, Ambassador Kennedy wired Rose that it would be acceptable to send Bobby to the local day school near their house in Bronxville, New York. Instead, Rose sent Bobby to Portsmouth Priory, a small boys’ school run by Benedictine monks. There is no record that Joe objected, or even particularly noticed.

The ambassador was intensely preoccupied at the time. On September 1, a few weeks before Bobby entered St. Paul’s, Germany invaded Poland. Ambassador Kennedy, who had hoped to hold back Hitler with appeasement, called President Franklin Roosevelt and cried out, “It’s the end of the world, the end of everything.” Kennedy was intensely fearful that his two draft-age sons, Joe Jr. and Jack, would be swept away by a world war. He was not unduly concerned with whether his third son was reading from a Protestant prayer book at morning chapel.

Set on a windswept hillside above Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, Portsmouth Priory aimed to funnel the sons of well-to-do Catholics to Harvard and Yale, not Holy Cross or Fordham. Supported by newly prosperous Irish families in Boston and New York, the school flourished at first. But when the Depression hit in the ’30s, the money for a second brick dormitory dried up. The boys lived in wooden prefabs so drafty that they hung blankets in the windows and mockingly called their school Beaverboard Prep.

Bobby was ill-suited to life in a boys’ dormitory. Not yet fourteen, he was shy and sweet. He had been very attentive to Luella Hennessey, his nanny. She recalled his making a great show of asking the police to stop traffic in busy London intersections so that she could cross the street. When she returned to the ambassador’s residence after a free afternoon, Bobby would rush past the footmen and swing open the door for her. Bobby was even more considerate to his mother. In the evenings, when Rose Kennedy went out, as she often did, he would wait by the front door to tell her how beautiful she looked. Years later Hennessey wondered if Bobby, sensing his mother’s loneliness and isolation, was trying to comfort her. “He was so close to her,” said Hennessey, adding, in an unguarded moment, “Someone had to be.”

Within his family, Bobby was described, with some derision, as his mother’s “pet.” To be allied with Rose was to be at the wrong end of the table in the Kennedy household. Within the Kennedy family there was a clear hierarchy of talents and expectations. The older boys and their sister Kathleen (“Kick”) were the “golden trio,” the children deemed most likely to succeed. Bright, athletic, outgoing, they shone in their father’s eye. His boundless ambitions lay with them, especially the oldest boy, Joe Jr. Lost in a crowd of younger girls—Eunice, Pat, and Jean—Bobby, born in 1925, ten years after Joe Jr. and eight years after Jack, had to turn to his mother for attention. Vivacious and intelligent as a young girl, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy was a proper and ambitious matron. But she had been subtly undermined, first by her dominating father, who denied her heartfelt wish to go to Wellesley and sent her to a convent school instead, and then by her husband, whose show of marital respect did not include fidelity. By the time Bobby was a boy in the early 1930s, Rose was somewhat fey and emotionally detached, consoling herself against Joe’s indiscretions by piety and periodic withdrawal into a make-believe world of fashion and royalty. Rose could join in the dinner table teasing and she still “managed” the family, setting schedules and acting as day-to-day disciplinarian, but Joe was the vital center. At family dinners, while Joe argued politics with Joe Jr. and John (switching sides from time to time to keep the debate alive), Bobby sat quiet and apart with the younger girls. Bobby’s grandmother, Josie Fitzgerald, worried about Bobby’s spending so much time surrounded by women. She feared he would become a “sissy.” Rose, too, worried that RFK would become “puny” and “girlish.” Joe Sr. seems to have written him off. Joe Kennedy wanted his sons to be conquerors, strong and independent men who could push their way into the Protestant establishment but owe loyalty to no one save their family. There was no room in this plan for a sweet momma’s boy. Lem Billings, Jack’s Choate roommate, remarked to Joe Sr. that Bobby was “the most generous little boy.” Joe Sr. gruffly replied, “I don’t know where he got that.” The only similarity between father and son that Billings could discern was in their eyes, a kind of icy pale blue.

The Kennedy household was full of laughter, but it was often at someone else’s expense. The older children learned to give back as good as they got. As a little boy, Bobby was not quick. He suffered in awkward silence or turned his humor on himself. Bobby was, in his father’s description, the “runt” of the family. He was not only smaller and slower than his brothers, he looked afraid. He lacked the jaunty, glowing air of a young Kennedy. A group portrait taken in about 1935, when Bobby was ten, shows the other Kennedy children looking sporty and sure. Bobby, however, perches by his mother’s side, his face tense with anxiety. His siblings cut him no slack. Teased hard, Bobby would look crushed. Rose would console him. “You’re my favorite,” she would say, in a half-kidding tone. In about 1939, the same year RFK left for boarding school, a friend asked his sister Eunice how the Kennedy brood was doing. All very well, except for Bobby, came the reply. He was “hopeless” and would “never amount to anything.” Many years later, Robert Kennedy seemed to have felt the same way about himself. He told writer Jack Newfield, “What I remember most vividly about growing up was going to a lot of different schools, always having to make new friends, and that I was very awkward. I dropped things and fell down all the time. I had to go to the hospital a few times for stitches in my head and my leg. And I was pretty quiet most of the time. And I didn’t mind being alone.”

At Portsmouth Priory, he was known as “Mrs. Kennedy’s little boy Bobby,” said David Meehan, his fourth form (sophomore) roommate. Robert would bring his mother around and gravely introduce her to the other boys, who predictably made fun of him and her. Bobby was hotly defensive of his mother. A boy in the class below, Pierce Kearney, passed along a mild dig he had heard from his own mother—that Mrs. Kennedy used so much lipstick she looked “like a Hollywood star.” Bobby screamed at Kearney, “How can you say such a thing!” and chased the younger boy out of the dormitory. Kennedy defended himself with a temper and a contemptuous air. He was regarded by most as standoffish. “He didn’t invite friends,” recalled Cleve Thurber, a classmate. “He wanted to be alone. This was his choice, but people saw it as snobbery.” In the survival-of-the-fittest world of an all-boys school and in the even more Darwinian competition of his own family, RFK discovered sarcasm as a defense. Eager to please, he was sweet. Unable to please, he was caustic. Kennedy was “not arrogant,” said another classmate, Frank Hurley, “but he had a sarcasm that could be biting.”

The monks who ran the school regarded him as a moody and indifferent student. “He didn’t look happy, he didn’t smile much,” said Father Damian Kearney, who was two classes behind RFK and later became a teacher at Portsmouth Priory (the school was renamed Portsmouth Abbey in 1967). According to Father Damian, who reviewed RFK’s records, Kennedy “was a poor-to-mediocre student, except for history.” He was a dogged but uncoordinated athlete. “Bob had trouble with his hands,” said Father Damian. “He dropped things. It was recommended that he squeeze a tennis ball. He was self-conscious about it until he was told that [heavyweight boxing champion] Gene Tunney did it.” (Kennedy’s tendency to drop things was “not a physical problem,” recalled his sister Eunice. “He just didn’t pay attention.”) Kennedy’s records show considerable correspondence between Mrs. Kennedy and the school. “She was intensely concerned about the minutiae. Nothing was too trivial,” said Father Damian. “Bob’s handwriting was atrocious. Couldn’t the school get a calligrapher for him?” Bobby Kennedy enjoyed a brief moment of fame when he spotted a fire in the barn then being used as a gym. Joe Kennedy Sr. gave the school $2,000 towards a new gym, almost enough, said Father Damian, “to build a squash court.”

Mostly, though, Bobby stood out for his religiosity. As a little boy, he had served as an altar boy at St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church in Bronxville. He was more pious than his siblings, showing off to them his knowledge of church Latin. Kennedys were taught that they belonged on a great stage. They were introduced by their ambitious father to the president, the pope, and the queen of England. They posed for newspapers and absorbed their father’s gospel of winning. The older, more confident children were clearly groomed to take their rightful place alongside the movers and shakers. For Bobby, the overlooked “runt,” the future was perhaps not so clear. But as an altar boy, he was able to play a small but indispensable role in reenacting the greatest drama in the history of the Christian world, Christ’s Last Supper. As he swung the censer and smelled the incense, waving the perfumed smoke in the processional, or ringing the bell as the priest consecrated the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, Kennedy could forget, for a moment, his insignificance at the family dinner table. He had found a place, a minor and subservient part, to be sure, in support of more blessed and worthy men, but still essential and charged with mystery and meaning.

At Portsmouth, where “most boys wore the Catholic mantle very lightly,” said his classmate Frank Hurley, Bobby went to mass more than the required three times a week and was often seen lingering afterwards, as if seeking refuge. He once prayed for three straight hours, though he was careful to mask the experience in self-deprecating sarcasm when he wrote home. “I feel like a saint,” he wrote, trying to be droll, lest anyone think he was taking himself too seriously.

Bobby could be dryly funny, but he was not lighthearted. He lacked the careless charm of his older siblings, who mocked him for his heaviness. His brother Jack, the Kennedy who worked the hardest at being effortless, called him Black Robert. In a later era of child-rearing, RFK would have been described, perhaps diagnosed, as depressed. In the summer of 1940, a few weeks after Bobby came home from his first year at Portsmouth, Rose wrote an anxious letter to Joe Sr. at the American embassy in London. Their son Jack, who had just graduated from Harvard, was having “the most astounding success” with his college thesis-turned-bestseller, Why England Slept, Rose reported. But “Bobby is a different mold. He does not seem to be interested particularly in reading or sailing or his stamps. He does a little work in all three, but no special enthusiasm. . . .” On July 11, she wrote Joe, “I am trying to get Bob to do some reading. He doesn’t seem to care for sailing as much as the other boys. Of course he doesn’t want to go to any of the dances. . . .” To not do the “work” of sailing at Hyannis was a significant dereliction. Kennedys were supposed to win on the water. In 1937, her first summer working as a nanny for the Kennedys, Luella Hennessey crewed for Jack in a race. When the wind began to die, he told her to jump overboard to lighten the boat and allow it to go faster. “He wasn’t kidding,” she recalled.

Other families muttered about the Kennedys’ win-or-else ethic. Joe Kennedy had brought his family to the low-key summer colony in the mid-1920s from slightly tonier Cohasset after he had been blackballed by the Cohasset Golf Club. The WASPs of Hyannis were somewhat more accepting, but anti-Irish prejudice lingered. The comfortable white-shingled house bought by Kennedy for his family was locally known as the Irish House. Decades later, members of the yacht club grumbled that the Kennedy children—frequent trophy winners in the 1930s—had cheated by adding extra canvas to their sails. The older siblings by and large ignored the sniping. But Bobby was more easily wounded. From an early age, he seems to have been the most self-consciously Irish of the brood, the one who identified most closely with the Irish history of oppression. In 1967, in an article in Look magazine, Bobby suggested that his father had left Boston in 1927 because of the signs that said “No Irish Need Apply.” An editor at another magazine wrote to gently chide him for exaggerating, pointing out that when Joe Kennedy’s family left Boston that year, it was in a private railway car. “Yes but—It was symbolic,” Bobby wrote back. “The business establishment, the clubs, the golf course—at least that was what I was told at a very young age. . . .”

Extremely defensive about his family, he seemed to have responded to his own low standing in the family hierarchy by adopting a rigid and fierce protectiveness about the family name. He was in awe of his father and older siblings; feeling insignificant, he may have felt that the family name was all he had. In the fall of 1940, his second year at Portsmouth, Joe Kennedy became the object of intense public scorn. The ambassador was increasingly pessimistic about the war raging in Europe. That November, he foolishly told some newspapermen, “Democracy is all done. . . . Democracy is finished in England. It may be here.” The remarks finished Kennedy as ambassador to England. At school, in angry shouting matches and sometimes with his fists, Bobby defended his father against charges of defeatism. When Kennedy Sr. slightly redeemed himself with a speech defending President Roosevelt’s lend-lease program for England in January, Bobby optimistically wrote his mother from school, “I listened to Daddy[’s] speech last night and I thought it was wonderful. I think it was the best speech that he ever made. I thought he really cleared himself from what people had been saying about him. . . .” Bobby had apparently been receiving some hate mail himself. In the same letter, he told his mother, “I got another one of those Post cards telling me like the last one how awful we Catholics are.”

From his spare and chilly dormitory, Bobby watched apprehensively as his family entered a bleak time in 1941. His post untenable, Joe Sr. came home in February. Roosevelt would not give his disgraced ambassador another appointment, at least not one Kennedy deemed worthy enough, so he brooded. Sitting with a friend in Palm Beach, he gloomily watched the ocean undermine the seawall in front of his house. He wasn’t going to fix it, he said. Let it go. The world was collapsing anyway. His oldest daughter, Rosemary, now twenty-three, was increasingly given to tantrums and outbursts. Kennedy was afraid that she would become uncontrollable and was especially fearful that she might throw herself at a man. That summer, he arranged to have her undergo a radical new medical procedure, a lobotomy, to cut off the frontal lobe of her brain. Something went wrong with the operation. Rosemary emerged not just quieter but zombie-like. Totally unable to care for herself, she had to be institutionalized.

Kennedy did not tell his own wife the nature of the operation. Rose was informed only that Rosemary, whom she had struggled to give a near-normal life, was being sent away, and that Rose—for her own good—would not be able to visit her for a long time. The rest of the family was told almost nothing. Their sister simply disappeared.

A mystery so strange and awful can haunt a family for generations. Yet the Kennedy children, Robert included, were accustomed to living with secrets. Joseph Kennedy was a secretive man. His phone was equipped with a special cupped mouthpiece to thwart eavesdroppers. He never discussed his business activities with his children. They could see him sitting in his “bullpen,” an enclosure that allowed him to conduct business while he sunbathed in Palm Beach or Hyannis. But they could only wonder to whom he was talking on the phone. He didn’t want them to know. His job was to make the money that would free them to follow more noble pursuits.

There were other secrets less well kept. Since the day in 1929 when Joseph Kennedy landed in Hyannis in an amphibious plane and stepped out with Gloria Swanson, his older children could not miss the parade of women on his arm. After his barely concealed affair with the movie goddess, there were more actresses and models and “secretaries” sitting beside Joe in the movie theater he built in the basement of the Hyannis house. In 1941, Jack casually talked to a friend about his father’s infidelities. He observed that Joe bought off Rose with presents, “a big Persian rug or some jewelry.”

Bobby probably knew less about his father’s indiscretions. But in his eagerness to please, he was keenly attuned to the moods of his parents. He must have sensed their remorse—and their alienation from each other—in the summer and fall of 1941. Like many sensitive children, he may have in some way blamed himself and tried even harder not to disappoint. His behavior in these months displays classic signs of teenage depression: withdrawal, overcompensation, then a self-destructive outburst to get attention.

Bobby was very down over Christmas vacation in Palm Beach during his third year at Portsmouth. His shyness became reclusiveness. Bobby is “very unsociable and should step out a little more,” Rose wrote Joe just after New Year’s 1942. “He absolutely refused to go to the Bath and Tennis [Club] and when he has gone out he doesn’t seem to like any of the boys here.” A week later, Bob’s dismal grades from school arrived. “I was so disappointed in your report,” Rose wrote her “favorite.” “The mark in Christian Doctrine was very low . . . Please get on your toes,” she instructed. “I do not expect my own little pet to let me down.” It is doubtful that she realized how anxious he was to please her—and even more so, his indifferent father. Shortly after this scolding, he tried to prove his faithfulness by sending his pious mother “two or three recommendations about serving mass.” He longed to correspond with his father about world events—he knew that Joe Jr. and Jack had routinely received missives from the ambassador. To prepare himself, Bob made his roommates quiz him every Sunday night on current affairs from the New York Times News of the Week in Review. But his father did not write. In Rose’s chatty, newsy missives to her children, Bobby is mentioned only in passing, usually after the exploits of the older children.

While generally inarticulate and diffident, Bobby was capable of sudden, almost wild acts that can be seen as cries for help. His father insisted on punctuality, so Bobby was, his mother recalled, “spectacularly prompt.” As a very little boy, rushing to make it to the table on time for dinner, he crashed through a glass partition, badly cutting his face. Slow to learn to swim, he apparently decided to hurry the process by plunging off a yawl into Nantucket Sound. His older bro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: Runt

- Chapter 2: Tough

- Chapter 3: Moralist

- Chapter 4: Manipulator

- Chapter 5: Protector

- Chapter 6: Testing

- Chapter 7: Goad

- Chapter 8: Intrigue

- Chapter 9: Play

- Chapter 10: Crisis

- Chapter 11: Brink

- Chapter 12: Causes

- Chapter 13: Threats

- Chapter 14: Worn

- Chapter 15: Mourner

- Chapter 16: Searcher

- Chapter 17: Conscience

- Chapter 18: Ghosts

- Chapter 19: Courage

- Chapter 20: Quest

- Chapter 21: Legend

- Photographs

- About the Author

- Source Notes

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photo Credits

- Copyright