eBook - ePub

Connections

About this book

Connections is a brilliant examination of the ideas, inventions, and coincidences that have culminated in the major technological achievements of today.

How did the popularity of underwear in the twelfth century lead to the invention of the printing press? How did the waterwheel evolve into the computer? How did the arrival of the cannon lead eventually to the development of movies?

In this highly acclaimed and bestselling book, James Burke brilliantly examines the ideas, inventions, and coincidences that have culminated in the major technological advances of today. With dazzling insight, he untangles the pattern of interconnecting events: the accidents of time, circumstance, and place that gave rise to the major inventions of the world.

Says Burke, "My purpose is to acquaint the reader with some of the forces that have caused change in the past, looking in particular at eight innovations—the computer, the production line, telecommunications, the airplane, the atomic bomb, plastics, the guided rocket, and television—which may be most influential in structuring our own futures....Each one of these is part of a family of similar devices, and is the result of a sequence of closely connected events extending from the ancient world until the present day. Each has enormous potential for humankind's benefit—or destruction."

Based on a popular TV documentary series, Connections is a fascinating scientific detective story of the inventions that changed history—and the surprising links that connect them.

How did the popularity of underwear in the twelfth century lead to the invention of the printing press? How did the waterwheel evolve into the computer? How did the arrival of the cannon lead eventually to the development of movies?

In this highly acclaimed and bestselling book, James Burke brilliantly examines the ideas, inventions, and coincidences that have culminated in the major technological advances of today. With dazzling insight, he untangles the pattern of interconnecting events: the accidents of time, circumstance, and place that gave rise to the major inventions of the world.

Says Burke, "My purpose is to acquaint the reader with some of the forces that have caused change in the past, looking in particular at eight innovations—the computer, the production line, telecommunications, the airplane, the atomic bomb, plastics, the guided rocket, and television—which may be most influential in structuring our own futures....Each one of these is part of a family of similar devices, and is the result of a sequence of closely connected events extending from the ancient world until the present day. Each has enormous potential for humankind's benefit—or destruction."

Based on a popular TV documentary series, Connections is a fascinating scientific detective story of the inventions that changed history—and the surprising links that connect them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Trigger Effect

In the gathering darkness of a cold winter evening on November 9, 1965, just before sixteen minutes and eleven seconds past five o’clock, a small metal cup inside a black rectangular box began slowly to revolve. As it turned, a spindle set in its centre and carrying a tiny arm also rotated, gradually moving the arm closer and closer to a metal contact. Only a handful of people knew of the exact location of the cup, and none of them knew that it had been triggered. At precisely eleven seconds past the minute the two tiny metal projections made contact, and in doing so set in motion a sequence of events that would lead, within twelve minutes, to chaos. During that time life within 80,000 square miles of one of the richest, most highly industrialized, most densely populated areas in the Western world would come to a virtual standstill. Over thirty million people would be affected for periods of from three minutes to thirteen hours. As a result some of them would die. For all of them, life would never be quite the same again.

The moving cup that was to cause havoc unparalleled in the history of North American city life was mounted inside a single back-up electric power relay in the Sir Adam Beck power station at Niagara Falls. It had been set to react to a critical rise in the power flowing out of the station towards the north; the level at which it would trip had been set two years before, and although power levels had risen in the meantime, the relay had not been altered accordingly. So it was that when power on one of the transmission lines leading from Beck to Toronto fluctuated momentarily above 375 megawatts, the magnets inside the rectangular box reacted, causing the cup to begin to rotate. As the spindle arm made contact, a signal was sent to take the overloaded power line out of the system. Immediately, the power it had been carrying was rerouted on to the other four northward lines, seriously overloading them. In response to the overload these lines also tripped out, and all power to the north stopped flowing. Only 2.7 seconds after the relay had acted the entire northward output automatically reversed direction, pouring on to the lines going south and east, into New York State and New York City, in a massive surge far exceeding the capacity of these lines to carry it. This event, as the Presidential Report said later, “occurring at a time of day in which there is maximum need for power in this area of great population density, offered the greatest potential for havoc”.

The first effect was to immobilize the power network throughout almost the entire north-east of America and Canada. Power to heat and light, to communicate and control movement, to run elevators, to operate pumps that move sewage, water and gasoline, to activate electronic machinery is the lifeblood of modern society. Because we demand clean air and unspoiled countryside, the sources of that power are usually sited at some distance from the cities and industries that need it, connected to them by long transmission lines. Due to the complex nature of the way our industrial communities operate, different areas demand power at different times; for this reason the transmission lines operate as a giant network fed by many generating stations, each one either providing spare power or drawing on extra, according to the needs of the particular area. As a result of this network, failure in one area can mean failure in all areas. The generators producing power for the transmission lines can be run at various speeds, which determine the frequency of the current; in order that all the inputs to a network may work together they must all be set to produce the same frequency, so the generators must run at whatever speed their design demands to produce that frequency. This maintains what is called a “stable” system. When something goes wrong, such as the massive overload of November 9, the system becomes wildly unstable. Protective devices automatically cut in, to protect individual generating stations from the overload by isolating them from the network. This means that they will then be producing either too much power for the local area, or too little. The sudden change in speed on the part of the generators to match output to the new conditions can cause serious damage, and for this reason the generators must be shut down.

This is what happened throughout most of north-east America in the twelve minutes following the relay operation at Beck. Over almost all of New York City the lights flickered and went out. Power stopped flowing to the city’s services. An estimated 800,000 people were trapped in the subways. Of the 150 hospitals affected, only half had auxiliary power available. The 250 flights coming into John F. Kennedy airport had to be diverted; one of them was on its final approach to landing when the lights on the runway went out, and all communication with the control tower ceased. Elevators stopped, water supplies dried up, and massive traffic jams choked the streets as the traffic lights stopped working. All street lighting went out in a city of over eight million inhabitants. To those involved the event proved beyond shadow of doubt the extent to which our advanced society is dependent on technology. The power transmission network that failed that night is a perfect example of the interdependent nature of such technology: one small malfunction can cripple the entire system.

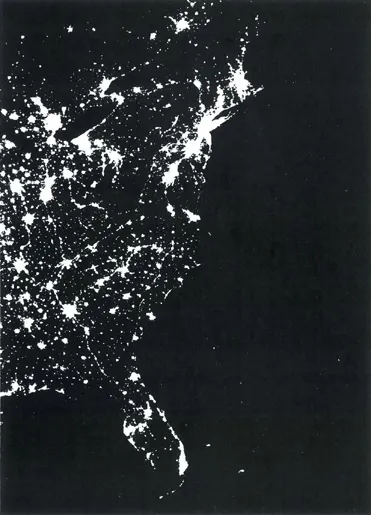

In this satellite photograph of the eastern seaboard of the United States, taken at night, the cities blaze with light, from Boston (top right) to Miami (bottom right). The area affected in the 1965 blackout ran north from New Jersey, and included the most highly illuminated concentration of population in the photograph, New York and Boston.

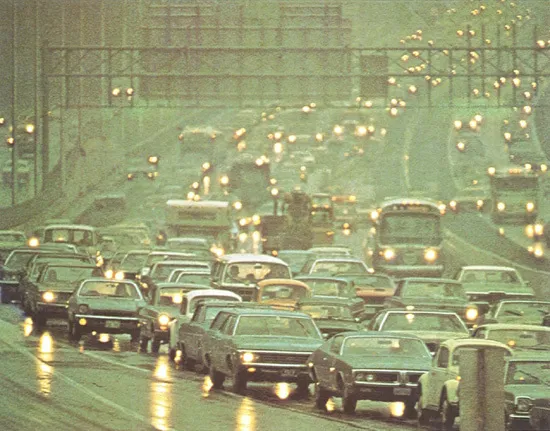

The prime example of man’s love—hate relationship with technology: the motor car, which makes mobility possible, and the traffic jam, which makes it impossible. Will freeways remain, long after the motor car has become obsolete, as monuments to the ability of technology to alter the shape of the world around us?

This interdependence is typical of almost every aspect of life in the modern world. We live surrounded by objects and systems that we take for granted, but which profoundly affect the way we behave, think, work, play, and in general conduct our lives and those of our children. Look, for example, at the place in which you are reading this book now, and see how much of what surrounds you is understandable, how much of it you could either build yourself or repair should it cease to function. When we start the car, or press the button in an elevator, or buy food in a supermarket, we give no thought to the complex devices and systems that make the car move, or the elevator rise, or the food appear on the shelves. Today we are almost totally dependent on the products of science and technology. They have already changed our lives: at the simplest level, the availability of transport has made us physically less fit than our ancestors. Many people are alive only because they have been given immunity to disease through drugs. The vast majority of the world’s population relies on the ability of technology to provide and transport food. There is enough food only because of the use of fertilizers. The working day is structured by the demands of the mass-production system. Roads are built to take peak hour traffic and remain half-empty outside those hours. We can neither feed, nor clothe, nor keep ourselves warm without technology.

The objects and systems produced by technology to perform these services operate interdependently and impersonally. A mechanical failure or industrial unrest in a factory that makes only one component of an automobile will affect the working life of thousands of other people working in different factories on other components of the same car. Step across the road into the path of an oncoming vehicle and your life may depend on the accuracy with which the brakes were fitted by someone you do not know and will never meet. A frost in Brazil may change your coffee-drinking habits by making the price prohibitive. A change of policy in a country you have never visited and with which you have no personal connections may radically alter your life—as was the case when the oil-producing states raised the price of oil in 1973 and thus set off rampant inflation throughout the Western world. Where once we lived isolated and secure, leading our own limited lives whose forms were shaped and controlled by elements with which we were intimately acquainted, we are now vulnerable to change which is beyond our own experience and control. Thanks to technology no man is an island.

Paradoxically this drawing-together of the community results in the increasing isolation of the individual. As the technological support systems which underpin our existence become more complex and less understandable, each of us feels less involved in their operation, less comprehending of their function, less confident of being able to operate without them. And although international airlines criss-cross the sky carrying millions of passengers every day, only a tiny fraction of the world’s population has ever flown, let alone visited a foreign country or learned a foreign language. We gain our experience of the world from television. The majority of the people in the advanced industrialized nations spend more time watching television than doing anything else besides work. We plug in to the outside world, enjoying it vicariously. We live with the modern myth that telecommunications have made the world smaller, when in reality they have made it immeasurably bigger. Television destroys our comfortable preconceptions by showing us just enough to prove them wrong, but not enough to replace them with the certainty of first-hand experience. We are afforded glimpses of people and places and customs as and when they become newsworthy—after which they disappear, leaving us with an uncomfortable awareness that we know too little about them.

In the face of all this most of us take the only available course: we ignore the vulnerability of our position, since we have no choice but to do so. We seek security in the routines imposed by the technological systems which structure our lives into periods of work and rest. In spite of the fact that any breakdown in our interdependent world will spread like ripples in a pool, we do not believe that the breakdown will occur. Even when it does, as in New York in 1965, our first reaction is to presume that the fault will be rectified, and that technology will, as it always has, come to the rescue. The reaction of most of the New Yorkers trapped in subways, elevators, or unlit apartment blocks was to reach out to the people immediately around them—not to organize their own escape from the trap, but to share what little warmth or food they had so as to pass the time until danger was over. To have considered the possibility that the failure was more than a momentary one would have been unthinkable. As one of the sociologists who studied the event wrote: “We can only conclude that it is too much to ask of us poor twentieth-century humans to think, to believe, to grasp the possibility that the system might fail . . . we cannot grasp the simple and elementary fact that this technology can blow a fuse.” The modern city-dweller cannot permit himself to think that his ability to cope in such a situation is in doubt. If he did so he would be forced to accept the uncertainty of his position, because once the meagre reserves of food and light and warmth have been exhausted, what then?

At this point another myth arises: that of the escape to a simpler life. This alternative was seriously considered by many people in the developed countries immediately after the rise in oil prices in 1973, and is reflected in the attitudes of the writers of doomsday fiction. The theory is that when sabotage or massive system failure one day ensures the more or less permanent disruption of the power supply, we should return to individual self-sufficiency and the agrarian way of life. But consider the realities of such a proposal. When does the city peasant decide that his garden (should he possess one) can no longer produce enough vegetables (should he know how to grow them and have obtained the necessary seeds and fertilizer) and animal protein and fats (should he know where to buy an animal and rear it) to support him and his family? At this stage, does he join (or worse, follow) the millions who have left the city because their supplies have run out? Since the alternative is to starve, he has no choice.

He decides to leave the city. Supposing he has the means of transport, is there any fuel available? Does he possess the equipment necessary for survival on the journey? Does he even know what that equipment is? Once the decision to leave has been taken, the modern city-dweller is alone as he has never been in his life. His survival is, for the first time, in his own hands. On the point of departure, does he know in which direction to go? Few people have more than a hazy notion of the agriculturally productive areas of their own country. He decides, on the basis of schoolbook knowledge, to head for one of these valleys of plenty. Can he continue to top up his fuel tanks for as long as it takes to get there? As he joins the millions driving or riding or walking down the same roads, does he possess things those other refugees might need? If so, and they decide to relieve him of them, can he protect himself? Assuming that by some miracle the refugee finds himself ahead of the mob, with the countryside stretching empty and inviting before him, who owns it? How does he decide where to settle? What does a fertile, life-sustaining piece of land look like? Are there animals, and if not, where are they? How does he find protection for himself and his family from the wind and rain? If shelter is to be a farmstead—has it been abandoned? If it has not, will the occupier be persuaded to make room for the newcomers, or leave? If he cannot be so persuaded, will the refugee use force, and if necessary, kill? Supposing that all these difficulties have been successfully overcome—how does he run a farm which will have been heavily dependent on fuel or electricity?

Of the multitude of problems lying in wait at this farm, one is paramount: can the refugee plough? Plants will grow sufficiently regularly only if they are sown in ploughed ground. Without this talent—and how many city-dwellers have it?—the refugee is lost: unless he has a store of preserved food he and his family will not survive the winter. It is the plough, the basic tool which most of us can no longer use, which ironically may be said to have landed us in our present situation. If, as this book will attempt to show, every innovation acts as a trigger of change, the plough is the first major man-made trigger in history, ultimately responsible for almost every innovation that followed. And the plough itself came as a result of a change in the weather.

At the end of the last ice age, in about 10,000 B.C., the glaciers began to retreat and the summer temperature began to rise. With the increase in temperature came a diminution of rainfall. This climatic change was disastrous for the hunting nomads living in the high grasslands: vegetation began to dry up and disappear, taking with it the herds on whose survival the nomads depended. Water became scarcer, and eventually, some time between 6000 and 5000 B.C., the hunters came down from the plateaux in search of regular food and water. They came down in northern India, central America, Syria and Egypt; they may also have come down in Peru. They came initially looking for animals which had themselves gone in search of water, and found it in river valleys. One of these valleys was uniquely suited to the development of a unified community: the Nile.

The nomads who, for example, descended to the rivers Tigris and Euphrates in Syria spread out and eventually formed themselves into individual city states. But in Egypt the new settlers found a fertile ribbon of land 750 miles long, limited on either side by inhospitable scrubland and desert; they were united by the continuity of the great river common to all. There was nowhere else to go. “Egypt”, said the Greek historian Herodotus, “is the gift of the Nile”. Initially the gift was of animals, sheltering in and living off the reeds and marshland along the edge of the river, and including birds, fish, sheep, antelope, wild oxen and game animals. As the settlers erected their primitive shelters against wind and rain and attempted to domesticate the animals—there are even records in their tombs of attempts to tame hyenas and cranes—someone may have noticed the accidental scattering by the wind of seeds on newly watered ground at the river’s edge, and the growth of new plants that followed. This action must have been imitated successfully, because at some time around 5000 B.C. the nomads decided not to move on as before, but to remain permanently. This decision can only have been made because of sufficient food reserves. The gift of the Nile was now something different from animals: it was fertility of soil.

The Nile itself is formed of two rivers, the White Nile, rising in the African lakes far to the south, and the Blue Nile, which falls from the Abyssinian plateau. One brings with it decaying vegetable matter from the lakes, and the other carries soil rich in potash from the plateau. This is a perfect mixture for fertilizing the ground. The land on the edge of the Nile had no need of manure. It would, with the minimum of tillage, produce full crops of emmer wheat and barley. Initially tillage was probably done by hand, the farmer merely breaking open the ground and laying the seeds in separate holes. But as this produced more grain to feed more mouths, the population must have increased to the point where such haphazard methods were insufficient, and the next step was taken. Pointed digging sticks pulled by hand would open the ground faster. The decisive event occurred some time befo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Description

- Author Bio

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Author’s Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Trigger Effect

- Chapter 2: The Road from Alexandria

- Chapter 3: Distant Voices

- Chapter 4: Faith in Numbers

- Chapter 5: The Wheel of Fortune

- Chapter 6: Fuel to the Flame

- Chapter 7: The Long Chain

- Chapter 8: Eat, Drink and Be Merry

- Chapter 9: Lighting the Way

- Chapter 10: Inventing the Future

- Further Reading

- Index

- Picture Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Connections by James Burke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.