eBook - ePub

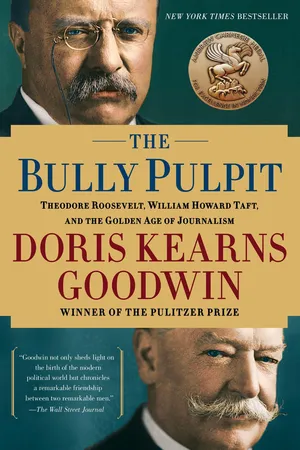

The Bully Pulpit

Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism

- 928 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Bully Pulpit

Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism

About this book

Pulitzer Prize–winning author and presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s dynamic history of Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft and the first decade of the Progressive era, that tumultuous time when the nation was coming unseamed and reform was in the air.

Winner of the Carnegie Medal.

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit is a dynamic history of the first decade of the Progressive era, that tumultuous time when the nation was coming unseamed and reform was in the air.

The story is told through the intense friendship of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft—a close relationship that strengthens both men before it ruptures in 1912, when they engage in a brutal fight for the presidential nomination that divides their wives, their children, and their closest friends, while crippling the progressive wing of the Republican Party, causing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to be elected, and changing the country’s history.

The Bully Pulpit is also the story of the muckraking press, which arouses the spirit of reform that helps Roosevelt push the government to shed its laissez-faire attitude toward robber barons, corrupt politicians, and corporate exploiters of our natural resources. The muckrakers are portrayed through the greatest group of journalists ever assembled at one magazine—Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and William Allen White—teamed under the mercurial genius of publisher S.S. McClure.

Goodwin’s narrative is founded upon a wealth of primary materials. The correspondence of more than four hundred letters between Roosevelt and Taft begins in their early thirties and ends only months before Roosevelt’s death. Edith Roosevelt and Nellie Taft kept diaries. The muckrakers wrote hundreds of letters to one another, kept journals, and wrote their memoirs. The letters of Captain Archie Butt, who served as a personal aide to both Roosevelt and Taft, provide an intimate view of both men.

The Bully Pulpit, like Goodwin’s brilliant chronicles of the Civil War and World War II, exquisitely demonstrates her distinctive ability to combine scholarly rigor with accessibility. It is a major work of history—an examination of leadership in a rare moment of activism and reform that brought the country closer to its founding ideals.

Winner of the Carnegie Medal.

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit is a dynamic history of the first decade of the Progressive era, that tumultuous time when the nation was coming unseamed and reform was in the air.

The story is told through the intense friendship of Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft—a close relationship that strengthens both men before it ruptures in 1912, when they engage in a brutal fight for the presidential nomination that divides their wives, their children, and their closest friends, while crippling the progressive wing of the Republican Party, causing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to be elected, and changing the country’s history.

The Bully Pulpit is also the story of the muckraking press, which arouses the spirit of reform that helps Roosevelt push the government to shed its laissez-faire attitude toward robber barons, corrupt politicians, and corporate exploiters of our natural resources. The muckrakers are portrayed through the greatest group of journalists ever assembled at one magazine—Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and William Allen White—teamed under the mercurial genius of publisher S.S. McClure.

Goodwin’s narrative is founded upon a wealth of primary materials. The correspondence of more than four hundred letters between Roosevelt and Taft begins in their early thirties and ends only months before Roosevelt’s death. Edith Roosevelt and Nellie Taft kept diaries. The muckrakers wrote hundreds of letters to one another, kept journals, and wrote their memoirs. The letters of Captain Archie Butt, who served as a personal aide to both Roosevelt and Taft, provide an intimate view of both men.

The Bully Pulpit, like Goodwin’s brilliant chronicles of the Civil War and World War II, exquisitely demonstrates her distinctive ability to combine scholarly rigor with accessibility. It is a major work of history—an examination of leadership in a rare moment of activism and reform that brought the country closer to its founding ideals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Bully Pulpit by Doris Kearns Goodwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Hunter Returns

Theodore Roosevelt receives a hero’s welcome in New York on June 18, 1910, following his expedition to Africa.

ROOSEVELT IS COMING HOME, HOORAY! Exultant headlines in mid-June 1910 trumpeted the daily progress of the Kaiserin, the luxury liner returning the former president, Theodore Roosevelt, to American shores after his year’s safari in Africa.

Despite popularity unrivaled since Abraham Lincoln, Roosevelt, true to his word, had declined to run for a third term after completing seven and a half years in office. His tenure had stretched from William McKinley’s assassination in September 1901 to March 4, 1909, when his own elected term came to an end. Flush from his November 1904 election triumph, he had stunned the political world with his announcement that he would not run for president again, citing “the wise custom which limits the President to two terms.” Later, he reportedly told a friend that he would willingly cut off his hand at the wrist if he could take his pledge back.

Roosevelt had loved being president—“the greatest office in the world.” He had relished “every hour” of every day. Indeed, fearing the “dull thud” he would experience upon returning to private life, he had devised the perfect solution to “break his fall.” Within three weeks of the inauguration of his successor, William Howard Taft, he had embarked on his great African adventure, plunging into the most “impenetrable spot on the globe.”

For months Roosevelt’s friends had been preparing an elaborate reception to celebrate his arrival in New York. When “the Colonel,” as Roosevelt preferred to be called, first heard of the extravagant plans devised for his welcome, he was troubled, fearing that the public response would not match such lofty expectations. “Even at this moment I should certainly put an instant stop to all the proceedings if I felt they were being merely ‘worked up’ and there was not a real desire . . . of at least a great many people to greet me,” he wrote one of the organizers in March 1910. “My political career is ended,” he told Lawrence Abbott of The Outlook, who had come to meet him in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, when he first emerged from the jungle. “No man in American public life has ever reached the crest of the wave as I appear to have done without the wave’s breaking and engulfing him.”

Anxiety that his star had dimmed, that the public’s devotion had dwindled, proved wildly off the mark. While he had initially planned to return directly from Khartoum, Roosevelt received so many invitations to visit the reigning European sovereigns that he first embarked on a six-week tour of Italy, Austria, Hungary, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway, Germany, and England. Kings and queens greeted him as an equal, universities bestowed upon him their highest degrees, and the German Kaiser treated him as an intimate friend. Every city, town, and village received him with a frenzied enthusiasm that stunned the most sophisticated observers. “People gathered at railway stations, in school-houses, and in the village streets,” one journalist observed. They showered his carriage with flowers, thronged windows of tenement houses, and greeted him with “Viva, viva, viva Roosevelt!” Newspapers in the United States celebrated Roosevelt’s triumphant procession through the Old World, sensing in his unparalleled reception a tribute to America’s newfound position of power. “No foreign ruler or man of eminence could have aroused more universal attention, received a warmer welcome, or achieved greater popularity among every class of society,” the New York Times exulted.

“I don’t suppose there was ever such a reception as that being given Theodore in Europe,” Taft wistfully told his military aide, Captain Archie Butt. “It illustrates how his personality has swept over the world,” such that even “small villages which one would hardly think had ever heard of the United States should seem to know all about the man.” The stories of Roosevelt’s “royal progress” through Europe bolstered the efforts of his friends to ensure, in Taft’s words, “as great a demonstration of welcome from his countrymen as any American ever received.”

In the week preceding his arrival in America, tens of thousands of visitors from all over the country had descended upon New York, lending the city’s hotels and streets “a holiday appearance.” Inbound trains carried a cast of characters “as diversely typical of the American people as Mr. Roosevelt himself . . . conservationists and cowboys, capitalists and socialists, insurgents and regulars, churchmen and sportsmen, native born and aliens.” More than two hundred vessels, including five destroyers, six revenue cutters, and dozens of excursion steamboats, tugs, and ferryboats, all decked with colorful flags and pennants, had sailed into the harbor to take part in an extravagant naval display.

An army of construction workers labored to complete the speaker’s platform and grandstand seating at Battery Park, where Roosevelt would address an overflow crowd of invited guests. Businesses had given their workers a half-holiday so they could join in the festivities. “Flags floated everywhere,” an Ohio newspaper reported; “pictures of Roosevelt were hung in thousands of windows and along the line of march, buildings were draped with bunting.”

The night before the big day, a dragnet was set to arrest known pickpockets. Five thousand police and dozens of surgeons and nurses were called in for special duty. “The United States of America at the present moment simulates quite the attitude of the small boy who can’t go to sleep Christmas Eve for thinking of the next day,” the Atlanta Constitution suggested. “And the colonel, returning as rapidly as a lusty steamship can plow the waves, is the ‘next day.’ It is a remarkable tribute to the man’s personality that virtually every element of citizenship in the country should be more or less on tiptoes in the excitement of anticipation.”

SHORTLY AFTER 7 A.M. ON June 18, as the bright rising sun burned through the mists, Theodore Roosevelt, as jubilant with anticipation as his country, stood on the bridge of the Kaiserin as the vessel headed into New York Harbor. Edith, his handsome forty-eight-year-old wife, stood beside him. She had journeyed halfway around the world to join him in Khartoum at the end of his long African expedition. Edith had found their year-long parting, the longest in their twenty-three years of marriage, almost unbearable. “If it were not for the children here I would not have the nervous strength to live through these endless months of separation from Father,” she wrote her son Kermit after Theodore had been gone only two weeks. “When I am alone & let myself think I am done for.”

Edith was no stranger to the anxiety of being apart from the man for whom she “would do anything in the world.” They had been intimate childhood friends, growing up together in New York’s Union Square neighborhood. She had joined “Teedie,” as he was then called, and his younger sister Corinne, in a private schoolroom arranged at the Roosevelt mansion. Even as children, they missed each other when apart. As Teedie was setting off with his family on a Grand Tour of Europe when he was eleven years old, he broke down in tears at the thought of leaving eight-year-old Edith behind. She proved his most faithful correspondent over the long course of the trip. She had been a regular guest at “Tranquillity,” the Roosevelts’ summer home on Long Island, where they sailed together in the bay, rode horseback along the trails, and shared a growing passion for literature. As adolescents, they were dancing partners at cotillions and constant companions on the social scene. Roosevelt proudly noted that his freshman college classmates at Harvard considered Edith and her friend Annie Murray “the prettiest girls they had met” when they visited him in New York during Christmas vacation.

In the summer of 1878, after his sophomore year, however, the young couple had a mysterious “falling out” at Tranquillity. “One day,” Roosevelt later wrote, “there came a break” during a late afternoon rendezvous at the estate’s summerhouse. The conflict that erupted, Roosevelt admitted, ended “his very intimate relations” with Edith. Though neither one would ever say what had happened, Roosevelt cryptically noted to his sister Anna that “both of us had, and I suppose have, tempers that were far from being of the best.”

The intimacy that Edith had cherished for nearly two decades seemed lost forever the following October, when Roosevelt met Alice Hathaway Lee. The beautiful, enchanting daughter of a wealthy Boston businessman, Alice lived in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, not far from Cambridge. The young Harvard junior fell in love with his “whole heart and soul.” Four months after his graduation in 1880, they were married. Then, in 1884, only two days after giving birth to their only child, Alice died.

A year later, Theodore resumed his friendship with Edith. And the year after that they were married. As time passed, Edith’s meticulous and thoughtful nature made her an exemplary partner for Theodore. “I do not think my eyes are blinded by affection,” the president told a friend, “when I say that she has combined to a degree I have never seen in any other woman the power of being the best of wives and mothers, the wisest manager of the household, and at the same time the ideal great lady and mistress of the White House.”

Their boisterous family eventually included six children. Three of the six were standing next to their parents on the bridge of the ocean liner: twenty-year-old Kermit, who had accompanied his father to Africa; eighteen-year-old Ethel; and twenty-six-year-old Alice, the child born to his first wife.

The girls had joined their parents in Europe. Along the rails of the four upper decks, their fellow passengers, some 3,000 in all, formed a colorful pageant as they waved their handkerchiefs and cheered.

Although wireless telegrams on board the ship had alerted Roosevelt to some of the day’s planned activities, he was surprised to learn that President Taft had assigned the massive battleship South Carolina as his official escort. “By George! That’s one of my ships! Doesn’t she look good?” an overwhelmed Roosevelt exclaimed when he saw her gray bulk pulling near. “Flags were broken out from stem to stern in the ceremony of dressing the ship,” reported the Boston Daily Globe, while “a puff from the muzzle of an eight-pounder” signaled the start of a 21-gun salute, the highest ceremonial honor, generally reserved for heads of state. Sailors clad in blue lined the decks of the warship, as the scarlet-uniformed Marine Band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The cannon roar of the South Carolina was followed by the rhythmic volley of salutes and whistles from the dozen or more additional naval ships in the bay. President Taft had clearly gone to great lengths, Captain Butt proudly noted, “to add dignity to the welcome and to extend a warm personal greeting to his predecessor.”

From the deck, Roosevelt spotted the tugboat carrying the reporters whose eyewitness accounts of the spectacular scene would dominate the news the following day. As he leaned over the rail and vigorously waved his top hat back and forth to them, they stood and cheered. To each familiar face, he nodded his head and smiled broadly, displaying his famous teeth, which appeared “just as prominent and just as white and perfect as when he went away.” Then, recognizing the photographers’ need to snap his picture, he stopped his hectic motions and stood perfectly still.

During his presidency, Roosevelt’s physical vigor and mental curiosity had made the White House a hive of activity and interest. His “love of the hurly-burly” that enchanted reporters and their readers was best captured by British viscount John Morley, who claimed that “he had seen two tremendous works of nature in America—the Niagara Falls and Mr. Roosevelt.” One magazine writer marveled at his prodigious stream of guests—“pugilists, college presidents, professional wrestlers, Greek scholars, baseball teams, big-game hunters, sociologists, press agents, authors, actors, Rough Riders, bad men, and gun-fighters from the West, wolf-catchers, photographers, guides, bear-hunters, artists, labor-leaders.” When he left for Africa, the “noise and excitement” vanished; little wonder that the members of the press were thrilled to see him return.

Shortly after the Kaiserin dropped anchor at Quarantine, the revenue cutter Manhattan pulled alongside, carrying the Roosevelts’ youngest sons, sixteen-year-old Archie and twelve-year-old Quentin, both of whom had remained at home. Their oldest son, twenty-two-year-old Theodore Junior, who was set to marry Eleanor Alexander the following Monday, joined the group along with an assortment of family members, including Roosevelt’s sisters, Anna and Corinne; his son-in-law, Congressman Nicholas Longworth; his niece Eleanor Roosevelt; and her husband, Franklin. While Edith anxiously sought a glimpse of the children she had not seen for more than two months, Roosevelt busily shook hands with each of the officers, sailors, and engineers of the ship. “Come here, Theodore, and see your children,” Edith called out. “They are of far greater importance than politics or anything else.”

Roosevelt searched the promenade deck of the Manhattan, reported the Chicago Tribune, until his eyes rested on “the round face of his youngest boy, Quentin, who was dancing up and down on the deck, impatient to be recognized,” telling all who would listen that he would be the one “to kiss pop first.” At the sight of the lively child, “the Colonel spread his arms out as if he would undertake a long-distance embrace” and smiled broadly as he nodded to each of his relatives in turn.

When Roosevelt stepped onto the crimson-covered gangplank for his transfer to the Manhattan, “pandemonium broke loose.” The ship’s band played “America,” the New York Times reported, and “there came from the river craft, yachts, and ships nearby a volley of cheers that lasted for fully five minutes.” Bugles blared, whistles shrieked, and “everywhere flags waved, hats were tossed into the air, and cries of welcome were heard.” Approaching the deck where his children were jumping in anticipation, Roosevelt executed a “flying leap,” and “with the exuberance and spirit of a school boy, he took up Quentin and Archie in his arms and gave them resounding smacks.” He greeted Theodore Junior with a hearty slap on the back, kissed his sisters, and then proceeded to shake hands with every crew member.

Around 9 a.m., the Androscoggin, carrying Cornelius Vanderbilt, the chairman of the reception, and two hundred distinguished guests, came alongside the Manhattan. As Roosevelt made the transfer to the official welcoming vessel, he asked that everyone form a line so that he could greet each individual personally and then went at the task of shaking hands with such high spirits, delivering for each person such “an explosive word of welcome,” that what might have been a duty for another politician became an act of joy. “I’m so glad to see you,” he greeted each person in turn. The New York Times reporter noted that “the ‘so’ went off like a firecracker. The smile backed it up in a radiation of energy, and the hearty grip of the hand that came down upon its respondent with a bang emphasized again the exact meaning of the words.”

When Rooseve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1. The Hunter Returns

- 2. Will and Teedie

- 3. The Judge and the Politician

- 4. Nellie Herron Taft

- 5. Edith Carow Roosevelt

- 6. The Insider and the Outsider

- 7. The Invention of McClure’s

- 8. “Like a Boy on Roller Skates”

- 9. Governor and Governor General

- 10. “That Damned Cowboy Is President”

- 11. “The Most Famous Woman in America”

- 12. “A Mission to Perform”

- 13. Toppling Old Bosses

- 14. “Thank Heaven You Are to Be with Me!”

- 15. “A Smile That Won’t Come Off”

- 16. “Sitting on the Lid”

- 17. The American People Reach a Verdict

- 18. “Cast into Outer Darkness”

- 19. “To Cut Mr. Taft in Two!”

- 20. Taft Boom, Wall Street Bust

- 21. Kingmaker and King

- 22. “A Great Stricken Animal”

- 23. A Self-Inflicted Wound

- 24. St. George and the Dragon

- 25. “The Parting of the Ways”

- 26. “Like a War Horse”

- 27. “My Hat Is in the Ring”

- 28. “Bosom Friends, Bitter Enemies”

- 29. Armageddon

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About Doris Kearns Goodwin

- Notes

- Illustration Credits

- Index

- Copyright