![]()

1

CITY OF GALLOWS

Roots of the Tyburn Tree

The shadow of the noose looms large over London’s history. Nowhere more so than at Tyburn, that desolate space beyond the city walls, where rebels, criminals and martyrs have been executed from time immemorial, as merciless governments strove to preserve an iron grip upon the populace. In the earliest years, offenders were hanged from the branches of the elm trees, until the development of purpose-built gallows, consisting of simple wooden structures with a transverse beam, from which the unfortunate prisoners dangled at the end of a very short rope.

Today, Marble Arch, surrounded by an endless flow of traffic, marks the spot where once the gallows stood. Eight hundred years ago, this windswept plain was silent, apart from the rustle of the elm trees and the caw of the carrion crow. Tyburn was located three miles north west of London for a reason. While the sight of a hanged man was believed to represent an effective deterrent, no citizen wanted to live alongside the reek of putrefaction. Tyburn also had its gibbets, metal cages in which the corpses of the hanged were displayed and left to rot. The mediaeval historian Matthew Paris recorded seeing two prisoners gibbeted, one already dead, the other still alive, condemned to die of exposure and starvation. Between executions, foxes, birds and badgers feasted on the ‘friendless bodies of unburied men’1 and scattered their remains across the heath.

On 6 April 1196, the stillness was shattered by the arrival of a roaring mob, and the pounding of hooves as a horse appeared in a cloud of dust over the horizon, dragging behind it the body of a man. This was the scene as William Fitzosbert, alias ‘Longbeard’, arrived at Tyburn to be executed for treason, the most grievous crime in the land. Plotting to overthrow the king and the state could only be punishable by death, and death of the most horrific and undignified kind. The sentence consisted of drawing, hanging and quartering, a barbaric practice which involved being dragged or ‘drawn’ to the gallows, then ‘hanged by the neck and let down alive’ before being disembowelled (another form of‘drawing’ when the intestines were ‘drawn’ from the body), burnt alive, beheaded, and hacked into four parts or ‘quarters’. Finally, the mutilated head and ‘quarters’ were put on display in prominent positions, such as Tower Bridge or the Temple Bar,pour décourager les autres.

Fitzosbert had already been stripped to the waist, bound hand and foot with rope, tied to the tail of a horse, and then ‘drawn’ or dragged from the Tower of London, a distance of over five miles. Many prisoners died of ‘drawing’ long before they reached the gallows.

As Fitzosbert was untied and hurled at the foot of the gallows, where a thick chain was placed around his neck preparatory to hanging, he must have reflected on the unhappy series of events that had brought him to this pass. For Fitzosbert had been a privileged man, even if the ‘Fitz’ in his name denotes that he was a ‘bastard’, born out of wedlock, to the affluent Osbert family. Fitzosbert, who was raised by his older brother and followed him into the family tailoring business, should have led a long and uneventful life, without troubling the history books. But Fitzosbert was the original bearded agitator.2 Despite the Norman fashion for a clean shave and cropped hair, Fitzosbert had retained the waist-length beard he had grown when serving on the Third Crusade. Indeed, Fitzosbert’s beard became a symbol of political resistance as he encouraged his Saxon supporters to follow his example, making them as unlike the Norman ruling class as possible.

Fitzosbert prided himself on challenging the authorities, denouncing the government from St Paul’s Cross, a prototype of Speakers’ Corner located in the precincts of St Paul’s Cathedral, where craftsmen and labourers flocked to hear him.3 Fitzosbert’s moment of glory finally arrived as a result of the imposition of a tax to secure the release of King Richard I, who had been kidnapped by Duke Leopold of Austria on his return from the Crusades. The Duke demanded £100,000 (around £20 million today) for his release. ‘Some citizens claimed, with considerable justification, that the Mayor and Corporation of London had assessed themselves and their friends lightly for the tax and passed the greater part of the burden on to their poorer neighbours.’4 In a bid to stop the tax, Fitzosbert sailed to France, where the king was held hostage, and explained his grievance to the king in person. Richard gave him assurances that he and his fellow Londoners would not be heavily taxed to raise funds for the ransom. Fitzosbert returned to London, where the authorities were waiting for him. A well-loved demagogue of the people he may have been, but Fitzosbert was not so popular with the Mayor of London and his aldermen, who were terrified that Fitzosbert would incite a tax riot. The government, headed by the Justiciar Hubert Walter in the absence of Richard I, shared their fears. Apprehensive that trouble in the City might spread to the outlying countryside, the authorities decided to move against him.

Barricading himself into his headquarters with a band of loyal supporters, Fitzosbert prepared for a long siege. But the authorities surrounded him, fearing that London would go up in flames. During the fighting that ensued, Fitzosbert killed one of the king’s men. Fitzosbert might have seized this opportunity to parade through London with a dripping sword, followed by hundreds of rebels. Instead, he was so horrified by the fact that he had killed a man that he fled to the nearby church of St Mary-le-Bow for sanctuary. Many of his supporters deserted him, and a mere nine men and his ‘concubine’ accompanied him into the church where he prepared to wait it out. Hubert Walter, the Justiciar, was faced with a dilemma. Should he defy ecclesiastical law and send in his men to arrest Fitzosbert and his supporters, with the attendant violence and possible killing, on holy ground? Or should he play a waiting game, until Fitzosbert ran out of food and ammunition and gave himself up?

The resourceful Hubert Walter formulated a plan. He ignored the time-honoured right of sanctuary and instructed his men to kindle a fire around the walls of the church. Coughing and spluttering, with streaming eyes, Fitzosbert and his followers were forced to abandon their sanctuary or choke to death on the fumes. One long-term consequence of this tactic was that the tower of St Mary-le-Bow collapsed in 1271, as a result of the fires lit to smoke Fitzosbert out.5 As they emerged into Bow Lane, Fitzosbert was attacked and wounded by the son of the man he had killed. Fitzosbert and his men were arrested, and Fitzosbert was tied up, fastened to a horse’s tail and dragged to the Tower to await trial for treason and the inevitable sentence of death.

And so Fitzosbert found himself at Tyburn, standing with a chain around his neck, awaiting the remainder of his sentence, which entailed being ‘hanged by the neck and let down alive’, then disembowelled while still conscious. He would then be faced with the grisly prospect of watching his own intestines burnt in front of him, before his head was cut off.

There are conflicting accounts as to how Fitzosbert responded to his final ordeal. Over one thousand years later, historians cannot agree on the exact circumstances of his death. According to the thirteenth-century Benedictine monk, Matthew Paris, a massive crowd turned out to pay their last respects to this people’s champion who had incited riots against an unfair tax. The Elizabethan historian John Stow, however, wrote that Fitzosbert died ignobly, blaspheming Christ, and calling ‘upon the devil to help and deliver him. Such was the end of this deceiver, a man of an evil life, a secret murderer, a filthy fornicator, a polluter of concubines, and a false accuser of his elder brother, who had in his youth brought him up in learning and done many things for his preferment.’6

Whatever the truth of his final moments, Fitzosbert’s execution was notable for two reasons. His death was the first recorded execution for treason at Tyburn, and it was also the first occasion upon which a victim of Tyburn had become a martyr. According to Matthew Paris, after Fitzosbert had been hanged in chains, his gibbet was carried off and treated as a holy relic by his supporters. ‘Men scooped the earth from the spot where [the gibbet] had stood. The chains which had held his decomposing body were claimed to have miraculous powers.’7 Fitzosbert was vindicated, having ‘died a shameful death for upholding the cause of truth and the poor’.

Fitzosbert’s status as a secular martyr did not prove popular with the authorities. The pilgrims who came to worship at Fitzosbert’s ‘shrine’ were driven away by Hubert the Justiciar, who had instigated the action against him. But Fitzosbert had his posthumous revenge. Two years later (1198), the monks of Canterbury complained to the Pope about Hubert’s conduct, claiming that he had violated the peace of the church of St Mary-le-Bow by forcing out Fitzosbert and his supporters. In response, the Pope put pressure on Richard I and Hubert was dismissed from his post as Justiciar.8

Fitzosbert’s status and crime made him eminent enough to enter the record books, while the thousands of humble thieves who perished at Tyburn were regarded as so unexceptional that they did not deserve a mention. Hanging had been introduced by the Anglo-Saxons during the fifth century as a punishment for murder, theft and treason. While William I repealed the death penalty, it was reinstated by Henry I in 1108. As Fitzosbert’s fate demonstrates, hanging served as a means of social and political control. According to the great Edwardian historian of Tyburn, Alfred Marks, ‘the country swarmed with courts of inferior jurisdiction, each with the power to hang thieves’.9 The law of the day had nothing to do with dispensing justice, and existed merely to defend property, which was regarded as more valuable than human life. The right to erect a gallows was granted to some surprising places, including monasteries. Despite the fact that England was nominally a Christian country, the church had no reservations about capital punishment, with St Paul and Thomas Aquinas enlisted in its defence.10 The treatment of criminals was governed not by the compassionate doctrines of the New Testament, but by the implacable concepts of the Old. Wrongdoers were publically punished, so that their agonies would be witnessed by as many people as possible, both for the retributive satisfaction and the deterrent effect.11

Although the priesthood were forbidden to shed blood, they were not banned from requesting their bailiffs to hang criminals. The Abbot of Westminster owned sixteen gallows in Middlesex in 1281, and the practice extended to convents. Geoffrey Chaucer’s tender-hearted prioress, Madame Eglantyne, who was said to weep at the sight of a mouse caught in a trap, would nevertheless have had a gallows on her property, upon which, at the hands of her bailiff, she would have hanged thieves.12

The gallows was a familiar sight throughout the land. One popular anecdote tells of a foreign traveller, who, having survived shipwreck, scrambled ashore on the English coast and found himself gazing up at what appeared to be a massive shrine. Crossing himself he fell to his knees, grateful to have arrived in a Christian country. But the structure he was kneeling before was in fact a gallows.13

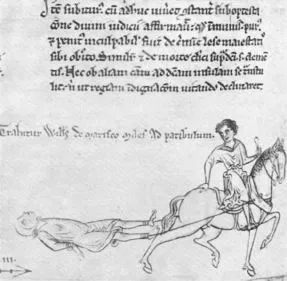

The very first recorded execution at Tyburn was that of John Senex, in 1177. Senex, a nobleman, had been the ringleader of a gang that perpetrated a series of burglaries on private houses in London. By 1236, when Henry III had ordered the King’s Gallows to be erected at Tyburn, it had become the place for men of rank to be executed, usually for treason. A notable case was that of William Marsh, who was not only drawn and hanged but quartered. Marsh, son of the viceroy of Ireland, was accused in 1235 of murdering Henry Clement, a messenger who interceded between the Irish and the king. Although he protested his innocence, Marsh was already under suspicion for the attempted assassination of the king. His assets were seized and he went on the run, eventually joining a gang of brigands on the island of Lundy, off the English south-west coast. Turning to a life of piracy, Marsh gave himself up to plunder and rape, as he and his gang descended suddenly on parties of unsuspecting travellers. Henry III put a price on Marsh’s head, and he was eventually betrayed by his comrades and ambushed by the king’s men, who brought him back to London and threw him into the Tower in 1242,14 with instructions that he ‘should be safely contained in the direst and most secure prison in that fortress, and so loaded with irons’ that there could be no risk of his escaping.15

On 25 July Marsh and sixteen of his henchmen went on trial at Westminster and were condemned to death by the king with immediate effect. Marsh was drawn from Westminster to Tyburn, and hanged from a gibbet. When his body was stiff it was cut down and disembowelled, and the bowels were at once burnt on the spot. And then, according to the chronicler, ‘the miserable body was divided into four parts, which were sent to four of the chief cities, so that this lamentable spectacle might inspire fear in all beholders’.16

Execution for Treason: William Marsh is dragged to Tyburn gallows, where he will be hanged and eviscerated. 1242.

Some fifty years later, the execution of Sir Thomas De Turberville for treason on 6 October 1295 is notable for the degree of humiliation the prisoner endured as he travelled to his death. De Turberville had been captured during the war with France and released on condition that he became a spy and conspired with the French to invade England and support the cause of William Wallace, the Scottish patriot. Detected in the act of writing to the Provost of Paris, De Turberville was tried and condemned. The unusual manner of his execution was described as follows. ‘He came from the Tower, mounted on a poor hack, and shod with white shoes, his being covered with a hood, and his feet tied beneath the horse’s belly, and his hands tied before him.’17 Riding alongside De Turberville were six torturers dressed up as devils, who hit him with cudgels and taunted him. Sitting on the horse with De Turberville was the hangman himself, grasping the horse’s bridle. De Turberville was led through London to Westminster Hall in this manner, where Sir Robert Brabazun pronounced judgement upon him, sentencing him to be drawn and hanged, ‘and that he should hang so long as anything should be left whole of him’.18 De Turberville was drawn on a fresh ox hide from Westminster to Cheapside, and then to Tyburn. The purpose of the ox hide was not humanitarian. Instead, this method was adopted so that the prisoner would not die before reaching the gallows.

De Turberville’s death was barbaric, even by the standards of the day. The fate that awaited William Wallace, the Scottish patriot, was even worse. Wallace (1272–1305) went on trial at Westminster Hall in 1305, although the trial itself was a travesty, and Wallace was forced to wear a crown of laurels as a mockery. He was condemned to be hanged and drawn for his ‘robberies, homicides and felonies’, and, ‘as an outlaw beheaded, and afterwards for your burning churches and relics your heart, liver, lungs, and entrails from which your wicked thoughts come shall be burned . . . ’19 Wallace’s execution included one refinement. ‘The Man of Belial’, as the chroniclers refer to him, was hanged on a very high gallows, specially built for the occasion, let down alive, then disembowelled before being beheaded and then undergoing the further indignity of ementulation or abscisis genitalibus.20 In other words, Wallace’s genitals were cut off his body and burnt.21 Finally, because all Wallace’s ‘sedition, depredations, fires and homicides were not only against the King, but against the people of England and Scotland’, Wallace’s head was placed upon Drawbridge Gate on London Bridge, where it could clearly be seen by travellers on land and water, and his quarters were hung in gibbets at Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling and Perth, ‘to the terror of all who pass by’.22 A year later, on 7 September, the head of Simon Fraser, another Scots rebel, was placed on Drawbridge Gate alongside that of his leader.

Brutal and barbaric as these methods of execution may appear to the modern reader, they were consequence of an unstable political climate. And as kings were believed to be divinely appointed, treason was regarded as a crime against God. They are perfect examples of the punishment being designed to fit the crime. But while the majority of convicted criminals awaited a predictable fate on the gallows, early records also yield some curious anecdotes, such as the fate of the ringleader of the first great robbery in the annals of London crime, and his cruel and unusual – but very apposite – punishment.

In 1303 the biggest robbery for six centuries was carried out in London, the amount involved being £100,000, or £20,000,000 in today’s currency. The target for the robbery was the palace of King Edward I, which at that period was located next to ...