- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

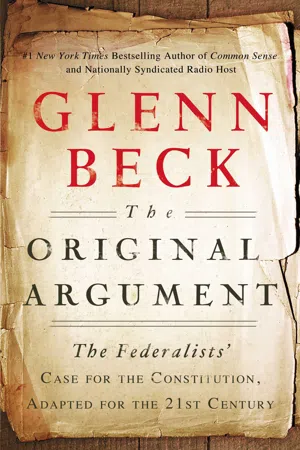

Glenn Beck, the New York Times bestselling author of The Great Reset, returns with his contemporary adaptation of The Federalist Papers with the inclusion of his own commentary and annotations to help readers interpret and understand the Constitution.

Glenn Beck revisited Thomas Paine’s famous pre-Revolutionary War call to action in his #1 New York Times bestseller Glenn Beck’s Common Sense. Now he brings his historical acumen and political savvy to this fresh, new interpretation of The Federalist Papers, the 18th-century collection of political essays that defined and shaped our Constitution and laid bare the “original argument” between states’ rights and big federal government—a debate as relevant and urgent today as it was at the birth of our nation.

Adapting a selection of these essential essays—pseudonymously authored by the now well-documented triumvirate of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—for a contemporary audience, Glenn Beck has had them reworked into “modern” English so as to be thoroughly accessible to anyone seeking a better understanding of the Founding Fathers’ intent and meaning when laying the groundwork of our government. Beck provides his own illuminating commentary and annotations and, for a number of the essays, has brought together the viewpoints of both liberal and conservative historians and scholars, making this a fair and insightful perspective on the historical works that remain the primary source for interpreting Constitutional law and the rights of American citizens.

Glenn Beck revisited Thomas Paine’s famous pre-Revolutionary War call to action in his #1 New York Times bestseller Glenn Beck’s Common Sense. Now he brings his historical acumen and political savvy to this fresh, new interpretation of The Federalist Papers, the 18th-century collection of political essays that defined and shaped our Constitution and laid bare the “original argument” between states’ rights and big federal government—a debate as relevant and urgent today as it was at the birth of our nation.

Adapting a selection of these essential essays—pseudonymously authored by the now well-documented triumvirate of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—for a contemporary audience, Glenn Beck has had them reworked into “modern” English so as to be thoroughly accessible to anyone seeking a better understanding of the Founding Fathers’ intent and meaning when laying the groundwork of our government. Beck provides his own illuminating commentary and annotations and, for a number of the essays, has brought together the viewpoints of both liberal and conservative historians and scholars, making this a fair and insightful perspective on the historical works that remain the primary source for interpreting Constitutional law and the rights of American citizens.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Original Argument by Glenn Beck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Freedom. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

NOVUS ORDO SECLORUM: A NEW ORDER FOR THE AGES

If you have a one-dollar bill handy, go ahead and pull it out. Turn it over to the back and look at the pyramid on the left. Beneath it you’ll find the Latin phrase NOVUS ORDO SECLORUM. It means “A New Order for the Ages” and it’s a permanent part of the Great Seal of the United States.

That concept—that America was creating something entirely new and historic—can also be found woven throughout the Federalist Papers. Read, for example, the words Alexander Hamilton chose for the introduction in Federalist 1:

“After an unequivocal experience of the inefficacy of the subsisting federal government,” he began, “you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world.”

It’s easy to forget that Americans were expecting the delegates they’d sent to Philadelphia to come back with a plan for how to amend the Articles of Confederation. Instead, they came back with a bold new vision for government—and a new constitution to match. But that didn’t make it an easy sell. People were justifiably concerned about the need to take such a dramatic step, and they were duly confused about exactly what the Constitution would mean for them personally.

Federalist 1 was Hamilton’s first chance to make the case that not only was a completely new document necessary, but also that the specifics of the document would make America, as he wrote later in Federalist 11, “the envy of the world.” He wanted readers to understand that the vision articulated in the Constitution wasn’t meek or timid but rather one that could point the world toward freedom.

History has proven that he was right.

Making the Case for Change

There are over 175,000 words in the Federalist Papers but perhaps none of them sum up the documents’ purpose as clearly and succinctly as these 46:

Nothing remains as obvious as the fact that either the new Constitution will be adopted, or the Union will be torn apart. It is therefore necessary to examine the advantages of the Union, as well as the evils and dangers that would result from its disbanding.

For Hamilton, it was do or die: Either the Constitution would be ratified or the young nation would die a premature death. For New Yorkers, the choice was even starker: ratify and join with the rest of the union, or stand aside even as the document was likely ratified without them, an event that might have resulted in the country’s being torn apart.

Yet instead of trying to frighten people with the dire consequences they might face should they not accept the Constitution, Publius calmly took on each of the legitimate objections being raised by critics.

First, they addressed the objections of the New Yorkers who were wondering what was wrong with the Articles of Confederation. These citizens claimed that the Constitutional Convention overstepped its boundaries by creating an additional document that wasn’t even necessary. These critics believed that the Articles themselves could simply be amended to strengthen the rule of law—as was the original plan. Publius would have to explain how the Constitution itself was necessary.

Next, Hamilton knew that he needed to explain why a national government over the states was preferable to one over individuals—and why a combination of states into a Union made sense. For citizens who were blindingly loyal to their individual states, this was a big mental hurdle to get past.

Then Hamilton wanted to paint a clear-eyed, panoramic picture of America’s economic peril. The states were awash in war debt and their use of paper money had spun out of control. Congress remained in gridlock and state administrations were woefully inefficient. And, as if all that weren’t enough, there was no consensus on trade policies and foreign affairs. To put it simply, America was in utter disarray. Hamilton wanted readers to come to grips with the reality and gravity of their situation as a means to understanding why such drastic change was necessary.

Additionally, Hamilton wanted his fellow New Yorkers to understand that the constitution under consideration represented something truly original: a pathway to the liberty they desired—one that empowered individuals to have a voice without threat of violence. This was a sharp break from the history of governments around the world. It was, after all, not just a minor tweaking of a government that had been tried before; it was a brand-new concept, an experiment in individual freedom that would allow man to govern himself.

Finally, Hamilton sought to explain how the Constitution would ensure a “firm and efficient” form of government. By “firm” he meant a government that had the strength to execute the duties and powers prescribed to it. But “efficient” was Hamilton’s driving focus. The theme of efficiency echoes throughout the Federalist Papers, and for good reason: Absent a common currency or standard federal tax policy, state governments struggled to maintain a semblance of effectiveness and, at times, even basic order.

Hamilton let readers know from the beginning that all of Publius’s arguments would be made in a civil tone, one worthy of the government they envisioned. Sure, the papers would call out the critics who were opposing the plan without even reading it, but Publius would avoid personal attacks. In fact, Publius could be the poster child for reasoned, rationale debate—a fact that is easy to overlook 225 years later but one that may have been key in bringing the country together. After all, it’s easy to point to all of the crises, wars, and revolutions throughout history that have been started by people looking to divide, attack, and marginalize. It’s much harder to find the instances of peace and unity brought on by those people who decided to do exactly the opposite. The Federalist Papers helped bring the country together.

One Nation, Under God

John Jay, who ended up contributing the fewest papers, wrote the next four opening papers (Federalist 2 through Federalist 5). While this set of essays eventually went into discussing the potential threat from foreign countries to the states, Jay started by picking up where Hamilton left off: with a pep talk.

The Constitution that was being debated, Jay reminded readers, was just that—a document that was being debated. It was being recommended to them, not forced on them, which he felt already made the process fairly unique in world history. People were having a real say as to whether some autocrat would have to be brought in, whether some title of nobility would be bestowed, or whether it was time to see if man was really capable of ruling himself.

Jay, of course, believed it was the latter—and he didn’t believe that the country had come to that moment in history through luck. He mentioned the word Providence three separate times in Federalist 2 alone, including this paragraph, which shows that Jay did not believe that the concepts “one nation” and “under God” were separate from each other.

This country and this people seem to have been made for each other, and it appears as if it was the design of Providence, that an inheritance so proper and convenient for a band of brethren, united to each other by the strongest ties, should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties.

It was God’s plan that the colonists eventually throw off a tyrant and experience freedom. Splitting apart would not only be foolish, Jay argued, but it would also be against God’s will.

Peace Through strength

The Founders understood that prosperity and national security depended on each other. Profits produce taxes, and taxes fund the military. It’s probably no coincidence, then, that America’s rise to prosperity coincided with the rise of our national strength and unity. But back then this wasn’t quite so obvious. Anti-Federalists believed that state sovereignty was paramount and that each state should be in charge of its own economy and security. In Federalist 11, Alexander Hamilton explained why that would never work.

Hamilton argued that a federal navy was necessary not only to ensure that business could run smoothly and grow quickly, but also to ensure that the world would take the country seriously. Thirteen independent navies each patrolling the waters off their own borders would be chaotic, to put it mildly.

In order for a national navy to be founded, however, the federal government first had to be given sovereign authority over commerce. Otherwise, there would be thirteen states making thirteen sets of commercial laws—all of which would be unenforceable by some centralized military force.

Think about it: The U.S. Navy protects the ports and passageways where large commercial ships voyage. This makes those waterways less vulnerable to attack or piracy, thereby giving consumers and merchants the confidence they need to buy, hire, and invest.

But what if each individual state had to create its own state navy to protect all the transoceanic commerce for businesses headquartered in that state only? Pennsylvania had to form a navy to protect Hershey’s chocolate-distribution channels, or Georgia had to forge a navy to guard Coca-Cola’s international shipping. What then?

In words that made some bristle, Hamilton compelled readers to “refuse, as Americans, to be the tools of European arrogance!” by unifying the states’ commercial interests so that the nation could “erect one great American system superior to all transatlantic force and influence” that is “capable of dictating the terms of connection between the Old and the New World!”

No King’s speech

Americans have never been unified by our politicians (that’s why approval ratings over 50 percent are considered high!), but rather by our common values and virtues. These principles, many of which are enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, make up the core of who we are.

This was in sharp contrast to Europe, where unity often sprang from royalty. The British were united because they all bowed before the same king. The Founders were decidedly anti-monarchical, and they wanted a Constitution that reflected this belief. Slogging through a bloody Revolutionary War only intensified their disdain for power based on privilege.

As a result, the Constitution bans titles of nobility. No kings and queens—only presidents, senators, representatives, and judges. To the greatest extent possible, the Founders sought to make family name and wealth irrelevant to one day being put in a position to lead. While the system isn’t perfect—the Kennedy and Bush families come to mind—it has resulted in many people being able to rise up through the system to reach a level of office that would have been virtually impossible in any other nation. Our current president comes to mind as an example of how well that imperfect system still works today.

Concerns about the imperfection of the Constitution almost led to its demise. Critics were out in force asking people why they would possibly approve a document that was, by everyone’s admission (even its most ardent supporters), imperfect. In Federalist 85, the last paper published, Hamilton confronted those people directly. Far from being a weakness, he explained, disagreements among the Constitution’s supporters merely demonstrate that unity and consensus on core principles take precedence over petty partisan squabbles.

And besides, Hamilton argued, the sinful nature of mankind naturally meant that a perfect system could never arise from imperfect men. As such, the best we could do was to craft the best document possible—and then amend it in the future as experience warranted.

A New Idea Is Born

Embedded throughout the Papers was a core belief that seemed to be manifesting itself publicly for the very first time: American exceptionalism. Since then, this belief has been at the center of America’s standing in the world, and stands at the center of how we carry ourselves as a nation.

American exceptionalism is the idea that America is not merely different from other nations and governments on earth—but exceptional among them. More specifically, it’s the belief that the hand of Providence brought together peoples of all colors and creeds to unite around a core set of universally shared values such as the rule of law, natural rights, and equality of opportunity to create a nation unlike any other across the arc of human history.

To some, American exceptionalism amounts to cheering for one’s own team, a puffed-up sense of superiority, or misplaced national pride. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay, and the rest of the Founders could not have disagreed more. They believed that, far from being about ego, American exceptionalism was the axis on which human freedom spins. If you don’t believe you are exceptional then who else will? If you don’t hold yourself up to the highest possible standards, then how can you expect to accomplish anything great? If you are unexceptional then you deserve to be ruled by others.

Unfortunately, some now believe that this concept is out of date. We may believe we are exceptional, they say, but other countries believe the same about themselves. That is simply not true. No other country has ever taken such a leap of faith with their future as our Founders did in the eighteenth century. A representative democracy, governing centrally over independent states to ensure the individual rights of man, wasn’t simply original, it was exceptional.

And it still is.

But perhaps even more exceptional was the idea that all of these concepts—many of them as foreign as they were complex—could be explained to average citizens in a way that provided them with the confidence they needed to move forward. Accomplishing that feat required someone with an outstanding grasp of history, civics, and human nature; someone who could be both logical and academic; someone who could speak to the elites and the working class simultaneously without upsetting either side; and someone who could take on the opposing arguments with a degree of civility that was v...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: The Birth of a Book about the Birth of Our Nation: How This Book Came to Be

- Introduction: The Great American Experiment: A User’s Guide

- Part One: Novus Ordo Seclorum: A New Order For The Ages

- Part Two: The Great Compromise

- Part Three: A Republic, If You Can Keep It

- Part Four: The Delicate Balance Of Power

- Part Five: Minimum Government, Maximum Freedom

- Part Six: Taxation With Representation

- Part Seven: Truth, Justice, And The American Way

- Appendixes The Constitution, with Footnotes to the Federalist Papers

- The Articles of Confederation

- John Jay’s Address to the People of New York

- Acknowledgments

- Footnotes

- Back Cover