- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

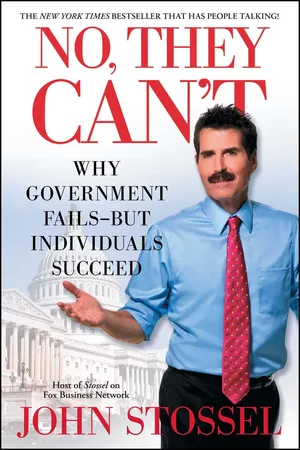

The government is not a neutral arbiter of truth. It never has been. It never will be. Doubt everything. John Stossel does. A self-described skeptic, he has dismantled society’s sacred cows with unerring common sense. Now he debunks the most sacred of them all: our intuition and belief that government can solve our problems. In No, They Can’t, the New York Times bestselling author and Fox News commentator insists that we discard that idea of the “perfect” government—left or right—and retrain our brain to look only at the facts, to rethink our lives as independent individuals—and fast.

With characteristic tenacity, John Stossel outlines and exposes the fallacies and facts of the most pressing issues of today’s social and political climate—and shows how our intuitions about them are, frankly, wrong:

• the unreliable marriage between big business, the media, and unions

• the myth of tax breaks and the ignorance of their advocates

• why “central planners” never create more jobs and how government never really will

• why free trade works—without government Interference

• federal regulations and the trouble they create for consumers

• the harm caused to the disabled by government protection of the disabled

• the problems (social and economic) generated by minimum-wage laws

• the destructive daydreams of “health insurance for everyone”

• bad food vs. good food and the government’s intrusive, unwelcome nanny sensibilities

• the dumbing down of public education and teachers’ unions

• how gun control actually increases crime

. . . and more myth-busting realities of why the American people must wrest our lives back from a government stranglehold.

Stossel also reveals how his unyielding desire to educate the public with the truth caused an irreparable rift with ABC (nobody wanted to hear the point-by- point facts of ObamaCare), and why he left his long-running stint for a new, uncensored forum with Fox. He lays out his ideas for education innovation as well and, finally, makes it perfectly clear why government action is the least effective and desirable fantasy to hang on to. As Stossel says, “It’s not about electing the right people. It’s about narrowing responsibilities.” No, They Can’t is an irrefutable first step toward that goal.

With characteristic tenacity, John Stossel outlines and exposes the fallacies and facts of the most pressing issues of today’s social and political climate—and shows how our intuitions about them are, frankly, wrong:

• the unreliable marriage between big business, the media, and unions

• the myth of tax breaks and the ignorance of their advocates

• why “central planners” never create more jobs and how government never really will

• why free trade works—without government Interference

• federal regulations and the trouble they create for consumers

• the harm caused to the disabled by government protection of the disabled

• the problems (social and economic) generated by minimum-wage laws

• the destructive daydreams of “health insurance for everyone”

• bad food vs. good food and the government’s intrusive, unwelcome nanny sensibilities

• the dumbing down of public education and teachers’ unions

• how gun control actually increases crime

. . . and more myth-busting realities of why the American people must wrest our lives back from a government stranglehold.

Stossel also reveals how his unyielding desire to educate the public with the truth caused an irreparable rift with ABC (nobody wanted to hear the point-by- point facts of ObamaCare), and why he left his long-running stint for a new, uncensored forum with Fox. He lays out his ideas for education innovation as well and, finally, makes it perfectly clear why government action is the least effective and desirable fantasy to hang on to. As Stossel says, “It’s not about electing the right people. It’s about narrowing responsibilities.” No, They Can’t is an irrefutable first step toward that goal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No, They Can't by John Stossel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“FIXING” THE ECONOMY

We spend too much time waiting for orders—and money—from Washington.

This happens because people think “something must be done” (by government) whenever bad things happen. When the housing bubble burst and stock prices tanked, President Obama told us: “The consensus is this: We have to do whatever it takes to get this economy moving again—we’re going to have to spend money now to stimulate the economy. . . .”

The idea, always implicit in the government’s thinking, but made explicit in the past few years, was that whatever the government spends money on will create a “multiplier effect”—that is, each dollar spent by the government will somehow generate more than a dollar’s worth of economic activity. That activity will create jobs.

The recession gave politicians a license to do what they wanted to do all along: spend. The usual checks on extravagance, weak as they are, were washed away. Budgets? We’ll worry about that later. Inflation? We’ll worry about that later.

A true free market doesn’t require much. It needs property rights, so no one can take your stuff. Then, people trade property to their mutual advantage, life never being perfect, but generally improving with each trade. Resources move around without the need for a central, coercive government telling people which resources should go where—or telling them that they must get permission to do what they think advantageous.

Ever see the website that tells the story of the guy who starts with a paper clip and trades his way up to a house? It was just a stunt, but that’s roughly what happens when the market is left alone. People combine resources in new ways to create wealth—and, in the process, jobs.

When President Obama took office, he promised to “save or create” 3.5 million jobs. Should we credit him for saving any jobs? He says that unemployment would be worse without his stimulus. But how can we know? I assume his spending on expensive government jobs crowded out better, more sustainable jobs.

If the economy recovers and President Obama claims he caused that, it wouldn’t be the first time a “leader” ran in front of a crowd and claimed to have led the way. But politicians don’t deserve credit for what free people do.

Given time, an economy, unless crippled by government intervention, will regenerate itself. The Keynesians in the administration said government had to “jump-start” the economy because businesses weren’t hiring. But an economy is not a machine that needs jump-starting. The economy is people who have objectives they want to achieve.

For now, the big-government media are baffled that big spending hasn’t paid off. “Companies are sitting on billions of dollars of cash. And still, they’ve yet to amp up hiring or make major investment,” wrote the Washington Post.

C’mon, Post, don’t blame the companies. CEOs don’t just wake up one day and decide not to hire. They hold back, quite reasonably, because they don’t know what obstacles they’ll face next. Will activist government prop up housing prices? Impose a new health-care mandate? Forbid me to move to South Carolina?

When rules are unpredictable or unintelligible (is the investment firm you use in compliance with the 2,300-page Dodd-Frank finance regulatory act?), then businesses hesitate to hire. When new employees are threats because byzantine Labor Department regulations make it impossible to fire them, businesses hesitate to hire. When tax increases lie ahead, businesses hesitate to hire. I don’t blame them.

Nothing more effectively freezes business than what historian Robert Higgs calls “regime uncertainty.”

Despite politicians’ talk of “giving” money to this or that (remember those tax rebate checks with President George W. Bush’s name emblazoned on them?), government has no money of its own. It has to take it from the private sector. Grabbing those scarce resources stifles the real economy.

One of the most important questions in politics should be: “Would the private sector have done better things with that money?” (And we should ask a similar question about the decision-making authority government takes from us every time it regulates.)

A healthy economy does not just create jobs-of-any-kind, it creates productive jobs. The pharaohs of ancient Egypt created plenty of jobs building pyramids, but who knows how much better the lives of ancient Egyptians (especially the slaves) might have been had they been free to engage in other work? They would all have had better housing, more food, or snazzier headdresses. Even as smart a person as economist John Maynard Keynes seemed to forget about that when he wrote in his General Theory back in 1936, “Pyramid-building, earthquakes, even wars may serve to increase wealth.”

By that logic, government could create full employment tomorrow by outlawing machines. Think of all the work there’d be to do then! Or government could hire people to dig holes and then fill them up (sadly, some government work resembles that).

Think about the two other methods to “increase wealth” that Keynes lumped in with pyramid-building: earthquakes and war. Now, sure, after a war or earthquake, there’s plenty of construction to be done. After the Haitian earthquake, Nancy Pelosi actually said, “I think that this can be an opportunity for a real boom economy in Haiti.” New York Times columnist Paul Krugman made a similar error. On CNN, he said if “space aliens were planning to attack and we needed a massive buildup to counter the space alien threat . . . this slump would be over in eighteen months.” Before that, he’d said the 9/11 attacks would be good for the economy.

This is Keynesian cluelessness at its worst. Sure, rebuilding after 9/11 or a Mars invasion would be good for the economy—but only if you ignore the fact that the same money and effort could have been used to make Crock-Pots, save for college, invest in Apple, or for countless other things.

Isn’t it obvious that those same workers could have done more productive work—with the resulting overall standard of living higher as a result? Does anyone really wish for earthquakes? There is something very wrong with mainstream politics and economics if some of its most respected practitioners overlook this point.

The economic philosopher Frédéric Bastiat called their mistake the “broken window fallacy.” If I break your window, it’s easy to see that I’ve given work to a glass-maker. But what we don’t see or think about is this: you would have done something else with the money you paid the glass-maker. That money would have created different jobs.

Reporters get confused by this. We favor government projects because we cover what is seen, not the unseen. The beneficiaries of the politicians’ conceit are visible. We see the windmills, solar farms, and housing subdivisions. The media see workers who got a raise from the new minimum wage. But we cannot see what didn’t happen because politicians acted. I cannot photograph the store that didn’t open because taxes went to homebuilders and solar farms. I cannot interview the worker never offered a job because the minimum wage priced him out of the market. I don’t even know who he is.

Creating jobs is not difficult for government. What is difficult is creating jobs that produce wealth.

As I write this, the New York Times reports that the Dodd-Frank regulation has been “a boon” to lawyers and corporate accountants. The article actually calls the regulations an “unofficial jobs creation act.”

Give me a break. Pyramids, broken windows, and extra accounting work do not produce wealth.

Under President Obama’s “stimulus” plan, jobs were created to weatherize buildings, build wind turbines, and repair roads. Politicians claimed these were valuable projects. But outside the market process, there is no way to know whether those were better uses of scarce capital than what would have been produced had the money been left in the private economy.

Since government services are funded through the compulsion of taxes, they have no market price. Without market prices, we have no way of knowing the importance that free people place on those services. We cannot calculate how much wealth we lose when politicians allocate resources.

Underlying President Obama’s (and Paul Krugman’s) call for more “stimulus” spending is the largely unexamined assumption that government spending will be more productive than spending by you and me.

But we don’t just throw our money off a cliff. We buy things. We invest, give to charity, save for college, save for retirement. All that is useful. Individuals do all kinds of things the government pretends that only it can do.

Krugman seems to think we’re all just goofing off here in the private sector, whereas the president and his wise advisers will steer money to truly productive uses, just as John Maynard Keynes believed back in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s day. Progressives say that FDR helped pull America out of the Great Depression. But his programs probably lengthened the Depression, even generating a depression within the Depression in 1937. Roosevelt’s Treasury secretary did complain: “After eight years of this administration we have just as much unemployment as when we started.” Sound familiar?

Amity Shlaes shows in her book The Forgotten Man that the New Deal failed because it interfered with the market’s natural regenerative processes. By creating uncertainty about what government would do next, government made businesses afraid to invest and hire. Again, sound familiar? Why expand if you fear new taxes? If you can’t even understand the rules?

U.S. politicians want to “support” the housing market. They’ve created housing subsidies, mortgage-backing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, and zero down payments. What great ideas! The subsidies and loan guarantees would help more people buy homes, and since homeowners are more responsible citizens, everything will be better.

You’ve seen the result.

By the way, Canada has no Fannie, Freddie, FHA, or zero down payment loans, yet Canadians have a higher rate of home ownership than...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Back Cover

- Description

- Author Bio

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Is There Anything Government Can’t Do? Well . . .

- Chapter 1: “Fixing” the Economy

- Chapter 2: Making Life Fair

- Chapter 3: Keeping Business Honest

- Chapter 4: Improving Life for Workers

- Chapter 5: Fixing Health Care

- Chapter 6: The Assault on Food

- Chapter 7: Creating a Risk-Free World

- Chapter 8: Making Sure No One Gets Offended

- Chapter 9: Educating Children

- Chapter 10: The War on Drugs: Because Alcohol Prohibition Worked So Well . . .

- Chapter 11: Wars to End War

- Chapter 12: Keeping Nature Exactly As Is . . . Forever

- Chapter 13: Budget Insanity

- Conclusion: There Ought Not to Be a Law

- Notes

- Acknowledgments