- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

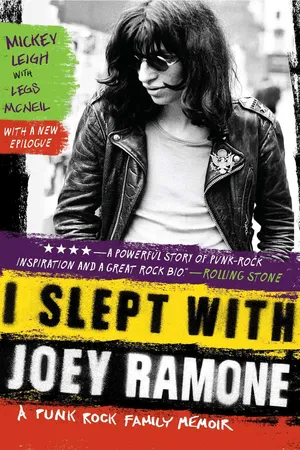

A “powerful” (Rolling Stone) memoir of the punk icons Ramones from front man Joey Ramone’s brother Mickey Leigh.

When the Ramones recorded their debut album in 1976, it heralded the true birth of punk rock. Legendary front man Joey Ramone gave voice to the disaffected youth of the seventies and eighties, and the band influenced the counterculture for decades to come. With honesty, humor, and grace, Joey’s brother, Mickey Leigh, shares a fascinating, intimate look at the turbulent life of one of America’s greatest—and unlikeliest—music icons. While the music lives on for new generations to discover, I Slept with Joey Ramone is the enduring portrait of a man who struggled to find his voice and of the brother who loved him.

When the Ramones recorded their debut album in 1976, it heralded the true birth of punk rock. Legendary front man Joey Ramone gave voice to the disaffected youth of the seventies and eighties, and the band influenced the counterculture for decades to come. With honesty, humor, and grace, Joey’s brother, Mickey Leigh, shares a fascinating, intimate look at the turbulent life of one of America’s greatest—and unlikeliest—music icons. While the music lives on for new generations to discover, I Slept with Joey Ramone is the enduring portrait of a man who struggled to find his voice and of the brother who loved him.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Slept with Joey Ramone by Mickey Leigh,Legs McNeil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music Biographies1.

I SLEPT WITH JOEY RAMONE—

AND HIS MOTHER TOO!

Our parents, Charlotte Mandell and Noel Hyman, grew up within a few miles of each other in Brooklyn, New York.

Oddly enough, they met for the first time over a hundred miles away at the Nevele Resort in the Catskills. The upstate resort area, also known as the “Borscht Belt,” had become a post–World War II hot spot for young Jewish singles looking to hook up.

Fortunately for my brother and me, not to mention millions of Ramones fans, our mom and dad did hook up, on New Year’s Eve in 1946.

They met when my mother, Charlotte, was nineteen. By the time she was twenty, she’d married Noel: “I wanted to get out of the house,” she said.

Our father’s parents were born in Brooklyn of European Jewish descent and humble means. Mom’s parents were also born in Brooklyn and Jewish, but were more affluent. Charlotte’s family wasn’t sure about the match.

“I wasn’t living up to my father’s expectations,” Charlotte explained. “In the beginning, Noel was fun. He was an older guy with a convertible. I wanted excitement in life, and so did he. We had a good time together.”

After their wedding, the couple moved into a modest flat on Ninety-fifth Street on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

Noel was the hardworking owner of a fledgling trucking company called Noel’s Transfer. Charlotte took a leave from her job as a commercial artist at an ad agency when she became pregnant with my older brother.

Jeffry Ross Hyman was born on May 19, 1951, at Beth Israel Hospital in downtown Manhattan. The young couple and their mutually ecstatic families celebrated the joy of Jeff’s arrival, but the blessed day did not pass without extreme distress. The major encumbrance in my brother’s life had actually formed before he’d ever taken his first breath. As nature would have it, a mass of what might have been another fetus that never developed had become attached to his spine. The medical term for the condition is “sacrococygeal teratoma”; it describes a type of tumor with cells vastly different from the surrounding tissue. It occurs once in every thirty-five to forty thousand births, with 75 percent affecting females. If the tumor is promptly removed, the prognosis is good. If elements of the teratoma are left behind—or diagnosis is delayed—the risk of malignancy increases. When he was born at six pounds, four ounces, the teratoma was the size of a baseball.

Surgery to remove the teratoma was extremely risky due to the location of the mass, but it was unavoidable, as far worse complications would occur if it were left intact. A few weeks later, when doctors deemed Jeff’s tiny body strong enough to withstand the trauma of surgery, the procedure was successfully completed. Some scarring of the spinal tissue was inevitable, which could cause neurological problems down the road. The extent of these problems was indeterminable at the time, but doctors were hopeful it wouldn’t have a devastating effect, if any, on Jeff’s development.

A relieved Mom and Dad nurtured Jeff back to health, and it appeared that my big brother was on his way to growing up a normal, happy boy.

About a year later, Dad, Mom, and Jeff headed to Queens, settling in a middle-class Jewish area called Forest Hills. They moved into a garden apartment snuggled in a corner of the neighborhood where the Long Island Expressway and the Grand Central Parkway intersect. Their apartment was conveniently located smack between the city’s two major airports, La Guardia and Idlewild Airport.

In front of the house, there was a footbridge that spanned Grand Central Parkway and took you into the huge Flushing Meadow Park, the site of the 1939 World’s Fair. The park featured Meadow Lake, where people could rent rowboats during the day and at night watch great displays of fireworks staged throughout the summer. Forest Hills was a friendly little community, a fun place for kids to grow up safe and sound.

THEN ONE NIGHT in October 1953, via Dad’s instinctive impulses and with Mom’s unyielding assistance, I began gathering myself together. Nine months later, I met up with them and Jeff for the first time.

They named me Mitchel Lee Hyman.

Born on July 15, 1954, in Forest Hills General Hospital, I passed inspection with only a couple of webbed toes noted on my permanent record. Dad drove us to the new house he’d recently purchased for the expanding family. It was right across the street from the garden apartment complex they’d lived in previously. Our house had a great little backyard with a small cherry tree, and as Jeff and I grew, so did the tree.

As far as my brother and I knew, we were a happy family then; but only a few years later, we began to hear harsh tones coming from our parents’ room. Jeff and I shared a bedroom down the hall from Mom and Dad’s, on the top floor of the house.

Jeff was a good big brother. When I would get scared at night, either from the boom of the fireworks across the lake or after seeing a scary movie like Invaders from Mars, The Crawling Eye, or The Thing, I’d run to his bed for protection.

“Jeff! Help!” I’d scream. “The monsters are under my bed and they’re trying to get in!”

“Come on in,” Jeff offered, pulling back the covers. “You can sleep with me. You’ll be safe here.”

Jeff was only five years old, but he seemed oblivious to the dangers that lurked under his bed. Maybe for Jeff, real life was scary enough; the crescentshaped scar across his lower back reminded him what real danger was.

Our friends David and Reba lived down the street, and our mom became well acquainted with their parents, Hank and Frances Lesher.

“I remember,” said David Lesher, “we used to run around in the parking lot by my house and make up crazy games, like Doody Boy.”

The game was basically tag with a glorified name. Instead of “it,” you were the “Doody Boy.” The main strategy was to not get stuck with the name at the end of the day, or you’d have to walk home with everybody laughing at you, yelling, “Hey, Doody Boy!” Somehow, Jeff often wound up the Boy.

One day, a bunch of us were playing in the dimly lit basement labyrinths of a nearby apartment complex.

All of a sudden, some kid yelled, “Run! There’s a ghost!”

We all screamed and bolted for the exit.

Even above the din of kids shrieking, everyone could hear the clang as my skull became intimate with an iron pipe in my path. I crumpled to the floor and started to cry. The next thing I knew, Jeff was picking me up and saying, “We better go home.”

Though everyone was running away, Jeff stayed to get me out of there.

Blood covered my eyes and face. Jeff put his arm around me, held my hand, and got me home to our horrified mom and dad, who rushed me to the doctor. I got my first taste of hard drugs and first feel of stitches—five of them, right in the middle of my head.

When the anesthesia began to wear off, I opened my eyes to see Jeff smiling down at me as he held a mobile of little colored airplanes above my head. He’d made it for me while I was sleeping.

“Do ya like it?” Jeff asked.

“Say thanks to your big brother,” Mom said to me. “He got you home.”

“Thanks, Jehhh . . . ,” I mumbled, still half-asleep, as Dad hung the mobile over my bed.

Actually Jeff and I didn’t call our father “Dad.” We called him “Bub,” a nickname we gave him when he’d come home shouting, “Hey Bub!” as he’d hoist us in the air.

“Hey Bub,” we’d shout back to him repeatedly, hoping for a second or third ride. The name stuck.

Our mom was loving and vibrant. She was always teaching us things, reading us stories, or showing us how to draw. She made sure we listened to all kinds of music, everything from kiddie songs to classics like Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf. We did everything together as a family. Mom, Dad, Jeff, and I would walk down the street, laughing, all holding hands.

We often had friends and family over for parties in the basement, where Jeff and I would provide the entertainment. We were comfortable playing that room. We would stand on top of the piano and sing songs like “When the Saints Come Marching In” and “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain.”

Grandma Fanny, Dad’s mom, bought Jeff an accordion, which he loved. He picked it up pretty quickly, playing everything in “oompah” time—probably from listening to too much Lawrence Welk. They got me a little ukulele, which I loved too. Unfortunately, I smashed it to pieces one night, after our “set,” by jumping off the piano and cracking the little uke on the basement floor. That made quite a memorable sound.

One day, after we’d come home from seeing our first circus at Madison Square Garden, Jeff exclaimed, “Hey! Let’s try the knife-throwing act!”

“Yeah!” I said. “Just like the Fantastic Fontaine Family!”

Jeff grabbed half a dozen steak knives from the kitchen. We went out on the grass by the side of the house, and I lay down with my arms and legs stretched out. Jeff made a drumroll sound.

As he let fly the first knife, Mom shrieked from the kitchen window, “Jeffry! Don’t you throw that knife!”—just as it sailed past my head.

“Aw, c’mon, Mom,” I explained. “We’re just playing circus!”

She came running out of the house with some paper and a box of crayons.

“Don’t you two ever play with knives again, you hear me? Here, play with these,” she said as she handed us the crayons.

As soon as Mom was out of sight, I stretched back out on the grass, Jeff made the drumroll sound—and he threw the crayons at me.

In the winter Mom and Dad would often take us upstate to Bear Mountain to go ice-skating or sleigh riding. At the end of the day, we’d go into the lodge and have dinner in front of the huge fireplace.

One time up at Bear Mountain a big motorcade pulled up just as we were about to enter the lodge. We were made to wait outside, along the path to the entrance, while a parade of police officers and men in suits escorted someone inside.

“It’s the president!” Dad yelled. “Wave to him, maybe he’ll say hello to you!”

Jeff and I looked at each other and then started jumping up and down, shouting, “Hey, President! Say hello!”

We were a little nervous. A few months earlier we’d been on the overpass above the Grand Central Parkway when a similar-looking motorcade had been passing underneath. That day, a bunch of us kids knocked some pebbles off the railing of the bridge that trickled down onto the cars below. Jeff Storch, the neighborhood bully, who frequently picked on my brother, threw a rock that made contact with one of the cars in the motorcade. Worse, some cops stationed on the overpass saw us all running away. Jeff and I were now afraid that the president was being escorted by those same cops—who might recognize us. But given that we didn’t want to tell our parents about that incident, we kept waving and shouting to the president.

As he came closer, we caught his attention. The president of the United States stopped for a second and summoned us past security. We thought we were in big trouble, but before we knew it, we were shaking hands with President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ike told us we’d better be good boys and listen to our parents.

We figured the president had pardoned us.

In the summer, we would walk over to Meadow Lake to go fishing, have picnics, and take out the rowboats. Dad taught us a game called Sink the Bismarck. We’d float a can or bottle in the water and throw rocks at it until it submerged. It was our favorite game, though neither of us knew what the hell the Bismarck was.

Jeff had a penchant for catching butterflies; he even had a mounting set. He would mount his bounty on a special board with little pushpins and write the name of the species in a designated space underneath. The Mammoth Viceroy was his prized catch. The only problem was that Jeff never followed the instructions for preservation correctly, and invariably they would dry up and turn into bug dust about a week later.

Jeff was as happy a kid as you could find in Forest Hills in the 1950s: rolling down the grassy hills laughing; standing up, spinning round and round in circles with his long gangly arms outstretched; then falling over like a drunken monkey.

Jeff would coax me to join him but warned, “Don’t throw up on me!”

I did both of the above.

We found ways to share just about everything, boosting each other up trees on sunny days and switching off verses of “Oh! Susanna” in the basement on rainy ones.

My big brother was outgoing and adventurous, cheerful and talented, and, as I said before, brave. He wasn’t weird. He wasn’t angry or removed or troubled or sickly or lonely or concerned. Jeff was the smiling, happy kid with the long legs, running through the thick grass, chasing butterflies, calling to me.

When I close my eyes and think of my brother, those are the first things I see.

2.

THE DAY THE MUSIC LIVED

When Jeff started first grade, it became apparent that he was having some difficulty learning to read, which prompted his teacher to suggest that my mother take him to the eye doctor. In addition to getting him glasses, Mom gave him a little tutoring in the mornings.

As a result, I got some residual “preschooling” at home. At breakfast Mom would teach Jeff the alphabet on big index cards. Though he was struggling, I could almost read before I started kindergarten.

One morning after Jef...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Front Flap

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- 1. I Slept With Joey Ramone— and His Mother Too!

- 2. The Day The Music Lived

- 3. “Do You Remember Rock ’N’ Roll Radio?”

- 4. “Wipeout!”

- 5. All Fall Down

- 6. The Hills Are Alive!

- 7. It Ain’t Us, Dad

- 8. Wild In The Streets!

- 9. The Seekers

- 10. “They’re Coming to Take Me Away!”

- 11. A Little Genius in Every Madman

- 12. In With The Outpatients

- 13. “I’m Eighteen and I Don’t Care”

- 14. Gall That Glitters

- 15. Out-Zapping Zappa

- 16. “1-2-3-4!”

- 17. Like Coffee for Jesus

- 18. Will The Kids be Alright?

- 19. “Today Your Love . . .”

- 20. “ . . . Tomorrow, the World”

- 21. “I Wanna be Sedated”

- 22. Ding Dong!

- 23. Alcoholic Synonymous

- 24. Grill the Messenger

- 25. Tomorrow Never Happens

- 26. I’ll Have the Happy Meal— To Go!

- 27. It’s The Rum Talking

- 28. “They Say It’s Your Birthday”

- 29. We’re the Monkeys!

- 30. “The Bottle is Empty, But The Belly is Full”

- 31. “Gimme Some Truth”

- 32. Clowns for Progress

- 33. Sibling Revelry

- 34. Murphy’s Roar

- 35. Lowlights in The Highlands

- 36. “Weird, Right?”

- 37. “Too Tough to Die”?

- 38. “Be My Baby”

- 39. The Old Man and The Seafood

- 40. A New Beginning for Old Beginners

- 41. “In A Little While”

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions

- Photo Insert

- Back Flap

- Back Cover