![]()

Part One

The Story of Catch-22

![]()

The Story of ‘Catch-22’

by Jonathan R. Eller

It shouldn’t have survived the first printing. It was a first novel by a part-time writer who had published very little since the 1940s. It was a book that captured the feelings of helplessness and horror generated by the darker side of the American dream at a time when the general reading public still expected fiction to reflect a positive view of contemporary America and its hallowed institutions. The title was changed twice during presswork; as if that weren’t enough, someone who thought he was portrayed in the book threatened to sue, prompting a name change for one of the main characters after almost a year in print.

But for a number of editors, advertisers, writers, and critics, reading the book echoed the opening line of the novel: “It was love at first sight.” This core of avid supporters kept the novel alive in the East Coast book market until word-of-mouth praise (and overnight bestseller status in Great Britain) took it to international prominence. In time, the title Catch-22 became a part of the English language, and Joseph Heller’s novel became an enduring part of American culture.

Heller was not unknown in publishing circles prior to Catch-22. His first published work appeared in the fall 1945 issue of Story, an issue dedicated to short fiction by returning servicemen. For several years after the war, he wrote what he called “New Yorker–type” stories about Jewish life in Depression-era Brooklyn. Several of these formula pieces were published in Esquire and the Atlantic Monthly while Heller was completing undergraduate work in English at NYU. These publications gained him some attention as a promising new writer, but he published no new stories after 1948—partly because they weren’t selling anymore, but primarily because he was ready to move on to more universal material:

By the time I was a senior in college, I’d done a little more reading and I began to suspect that literature was more serious, more interesting than analyzing an endless string of Jewish families in the Depression. I could see that type of writing was going out of style. I wanted to write something that was very good and I had nothing good to write. So I wrote nothing.1

Instead, he began graduate studies in English at Columbia, which he would complete with an M.A. in 1949, followed by an additional year at Oxford on a Fulbright Scholarship. After two years teaching expository writing at Pennsylvania State University, Heller moved back to New York in 1952 and took a job writing for a small advertising agency, and later for Remington Rand. Graduate work provided the insight required to attempt serious literature, and Heller wanted to write a novel. The drive developed tentatively and without much outside inspiration. He was generally disappointed by the new novels of the early postwar years: “There was a terrible sameness about books being published and I almost stopped reading as well as writing.” He considered the war novels of Jones, Miller, Shaw, and others quite good, but he did not at first consider his own wartime experiences as subject for fiction. Nearly thirty typescripts accumulated by 1952, but only one—the never-published “Crippled Phoenix”—offered a hint of the wartime traumas that would surface in Catch-22.

In 1953, he began a series of notecards outlining characters and a military scenario for what would become Catch-22. Certainly his wartime experiences, and those of boyhood friends like George Mandel, formed a basis for the new project. Mandel, who had been seriously wounded as an infantryman in Europe, would eventually write The Wax Boom (1962), a tough war novel that also questioned traditional army chain-of-command responses to combat situations. Mandel remained a responsive and insightful reader for Heller during the seven years that Catch-22 evolved.

A photograph from Joseph Heller’s copy of the 488th Squadron’s unofficial scrapbook. Heller is on the right.

But in 1953, Heller was still searching for the right form and style of expression. In literature, he found himself attracted to the innovative work of Waugh, Nabokov, and Céline for their successes in achieving the kind of effect Heller wanted. In an early post-publication interview, Heller used Nabokov’s work to describe the effect he himself was searching for: “Nabokov in Laughter in the Dark takes an extremely flippant approach to situations deeply tragic and pathetic, and I began to try for a similar blending of the comic and the tragic so that everything that takes place seems to be grotesque yet plausible.”2

From a publishing perspective, however, it was Heller’s interest in Céline that finally sparked a marketable product. Heller had read Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night while teaching at Penn State; sometime later, probably in 1954, he read Céline’s Death on the Installment Plan. Céline’s experimentation with time, structure, and colloquial speech profoundly affected him, and triggered a crucial burst of creative energy. Heller recalled the event for his 1975 Playboy interview with Sam Merrill:

I was lying in bed, thinking about Céline, when suddenly the opening lines of Catch-22 came to me: “It was love at first sight. The first time he saw the chaplain, Blank fell madly in love with him.” I didn’t come up with the name Yossarian until later, and the chaplain wasn’t necessarily an Army chaplain. He could have been a prison chaplain. Ideas of plot, pace, character, style, and tone all tumbled out that night, pretty much the way they finally appeared in the book. The next morning, at work, I wrote out the whole first chapter and sent it to my agent, Candida Donadio, who sold it to New World Writing.

Donadio offered “Catch-18” to Arabel Porter at New American Library’s Mentor Books, and immediately found another enthusiastic fan; Porter wanted “Catch-18” for the Seventh Mentor Selection of New World Writing, an NAL series dedicated to publishing the best new literature and criticism. Other NAL editors concurred in superlative terms; Walter Freeman believed that “Of all the recommended pieces lately, this stands out. It seems like part of a really exciting, amusing novel.” Founding editor Victor Weybright was convinced that “Catch-18” was the “funniest thing we have ever had for NWW.”3

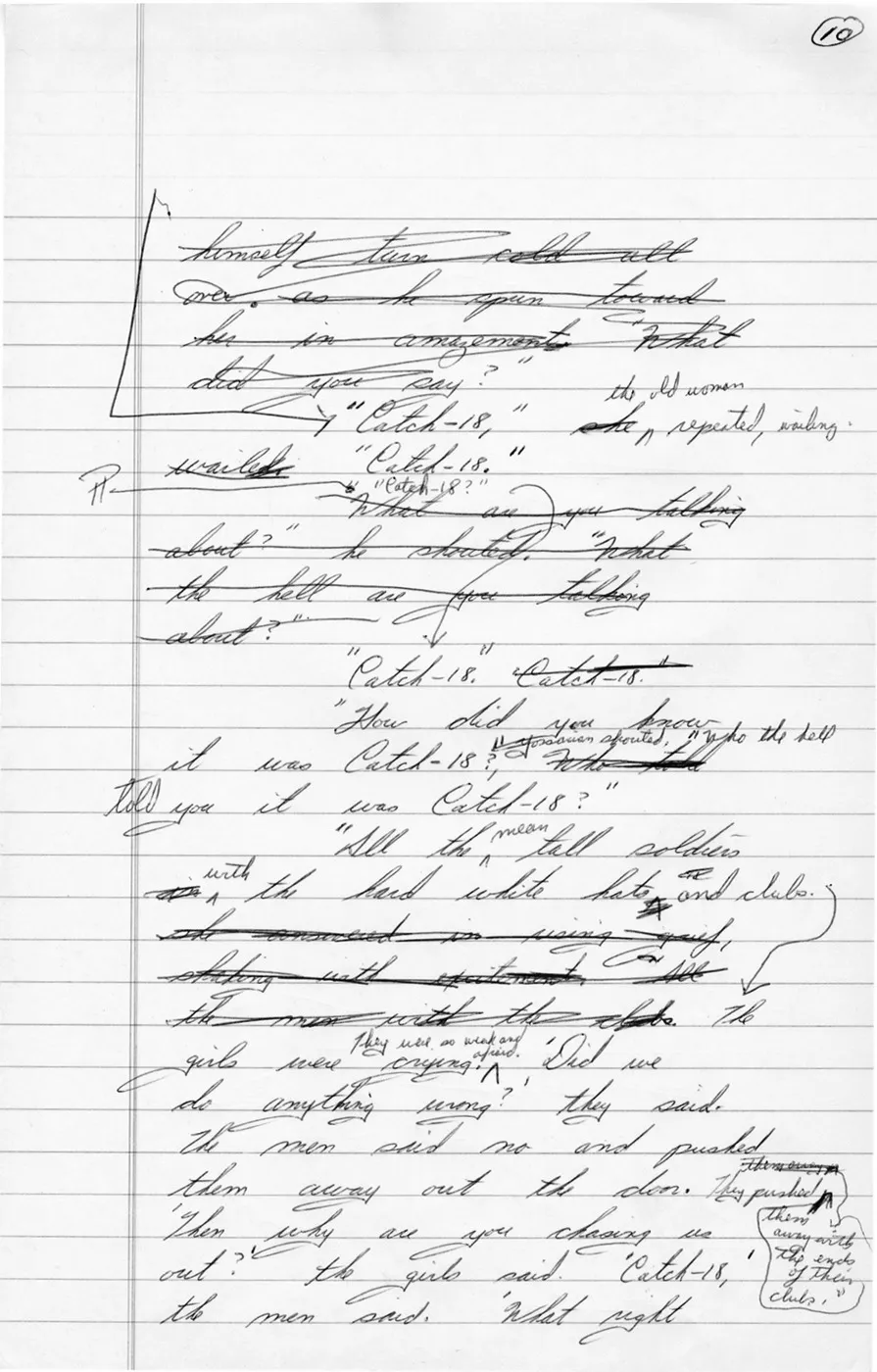

Although Heller was already referring to his initial experiment as a prospective novel, it would be a year before he completed the next chapter, and two years before he finished enough material to send out the story for further review. The main problem was time: between business and family responsibilities, Heller was only able to work on Catch-18 in the evenings, and never very late. He worked slowly and revised extensively at the kitchen table in his West End Avenue apartment, completing about three handwritten pages each night on yellow legal tablets. By day he continued in advertising, moving to successively better-paying positions at Time in 1955 and Look in 1956. In 1957 he moved into the Advertising-Promotion Department at McCall’s, where he would remain until Catch-22 changed his life forever.

By the summer of 1957, Heller had completed enough to make a seventy-five-page typescript. In August, Candida Donadio circulated the typescript and received offers from Bob Gottlieb at Simon and Schuster and Tom Ginsberg at Viking. Each offered options to draw a contract when the book was complete; author and agent passed on both, opting to develop more of the book and then ask for an immediate contract.

In February 1958, Donadio sent a longer typescript to Bob Gottlieb, who had shown a very strong interest the previous summer. By this time, Heller had finished seven handwritten chapters and revised them into a 259-page typescript. This typescript eventually became the first third of the book, evolving into the first sixteen chapters of the final novel. Gottlieb, at twenty-six the youngest editor at Simon and Schuster, loved what he saw of the book and arranged a contract for Heller, but not without a struggle.

Four members of the editorial board reported on the manuscript: Gottlieb, administrative editor Peter Schwed, Justin Kaplan (then an executive assistant to Henry Simon and Max Schuster), and Henry Simon, younger brother of founder Richard Simon and by 1958 a vice president. In his report, Gottlieb wrote:

I still love this crazy book and very much want to do it. It is a very rare approach to the war—humor that slowly turns to horror. The funny parts are wildly funny, the serious parts are excellent. The whole certainly suffers somewhat by the two attitudes, but this can be partly overcome by revisions. The central character, Yossarian, must be strengthened somewhat—his single-minded drive to survive is both the comic and the serious center of the story.4

A page from the early manuscript, with revisions by Heller.

Gottlieb was the strongest advocate, and both Schwed and Kaplan found it wildly funny but at times repetitive. Even Gottlieb conceded that the book would not be a big seller, although he felt that it was “bound to find real admirers in certain literary sets.” Henry Simon, however, found Yossarian’s escapades repetitive and at times offensive, and recommended against publication. In the end, Heller’s willingness to make revisions, and Gottlieb’s willingness to work with him, convinced the board to contract the book.

The 1955 appearance of chapter 1 in New World Writing had introduced the publishing world to Catch-18, and by the end of the decade news about the novel had spread by word of mouth from Heller’s agent, his publisher, and his own circle of friends and advertising associates. His contract had originally called for 1960 publication, but Heller needed all of 1960 to finish the manuscript and work it into shape for publication. By this time the 259-page typescript of 1958 had more than doubled in length; Heller had extended the existing episodes by interleaving handwritten pages of the familiar legal-sized yellow paper into the typescript, thus expanding it from seven to sixteen chapters (through “Luciana,” chapter 16 of the final work) without altering the order and basic structure of the earlier draft. But a major new manuscript section picked up where the original circulating typescript left off, adding another twenty-eight chapters to the increasingly complex narrative. Chapter 39, “The Eternal City,” had proven most troublesome; it took months to refine the dark tones of Yossarian’s final trip to Rome and create a smooth transition into the revelations of the novel’s concluding chapters.

During 1960, Heller prepared a new 758-page typescript from this conflation, and made revisions that included deletion of the original manuscript chapter 18, “Rosoff.” This chapter provided a chronological bridge between the “Soldier in White” chapter, set in the hospital on Pianosa, and “The Soldier Who Saw Everything Twice” chapter, a flashback into Yossarian’s earlier hospital episodes at Lowry Air Base in Denver, Colorado. The deleted chapter included an overlong but delightful digression into “PT” and team sports at Lowry, but Heller soon sensed that this interlude impeded the progress of the narrative. Other digressive episodes would have to be cut as well before the book would go to press.

With the newly revised typescript in hand, Heller and Gottlieb made further revisions in the text. After a series of editorial sessions, Heller shortened the typescript by about 150 pages. The typescript, now heavily revised and partially retyped, became printer’s copy for the Simon and Schuster galley proofs. Before the text was actually set, Heller worked with Gottlieb on some final cuts, including the original chapter 23 (“The Old Folks at Home”), a digre...