eBook - ePub

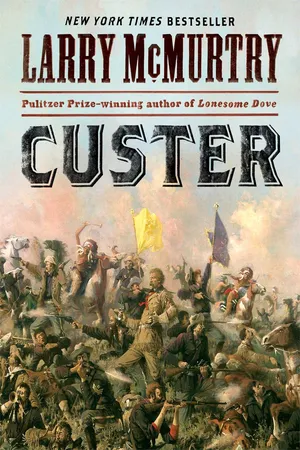

Custer

About this book

This lavishly illustrated volume reassesses and celebrates the life and legacy of the West’s most legendary figure, George Armstrong Custer, from “one of America’s great storytellers” (The Wall Street Journal).

On June 25, 1876, General George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry attacked a large Lakota Cheyenne village on the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory. He lost not only the battle but his life—and the lives of his entire cavalry. “Custer’s Last Stand” was a spectacular defeat that shocked the country and grew quickly into a legend that has reverberated in our national consciousness to this day.

In this lavishly illustrated volume, Larry McMurtry, the greatest chronicler of the American West, tackles for the first time the “Boy General” and his rightful place in history. Custer is an expansive, agile, and clear-eyed reassessment of the iconic general’s life and legacy—how the legend was born, the ways in which it evolved, what it has meant—told against the broad sweep of the American narrative. It is a magisterial portrait of a complicated, misunderstood man that not only irrevocably changes our long-standing conversation about Custer, but once again redefines our understanding of the American West.

On June 25, 1876, General George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry attacked a large Lakota Cheyenne village on the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory. He lost not only the battle but his life—and the lives of his entire cavalry. “Custer’s Last Stand” was a spectacular defeat that shocked the country and grew quickly into a legend that has reverberated in our national consciousness to this day.

In this lavishly illustrated volume, Larry McMurtry, the greatest chronicler of the American West, tackles for the first time the “Boy General” and his rightful place in history. Custer is an expansive, agile, and clear-eyed reassessment of the iconic general’s life and legacy—how the legend was born, the ways in which it evolved, what it has meant—told against the broad sweep of the American narrative. It is a magisterial portrait of a complicated, misunderstood man that not only irrevocably changes our long-standing conversation about Custer, but once again redefines our understanding of the American West.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

AT ONE TIME A PICTURE called Custer’s Last Stand hung in virtually every saloon in the land, and quite a few barbershops too. I first saw it in our small barbershop, in Archer City, Texas. A painting by Cassilly Adams, lithographed by Otto Becker, was given away by the thousands by Anheuser-Busch, the great brewing enterprise of St. Louis: General George Armstrong Custer, long locks flying, was fighting on staunchly against terrible—in fact impossible—odds. And when he fell, along with some 250 of his men, the world was no longer the same.

Buffalo Bill Cody often used a skit called “Custer’s Last Rally,” as the finale of his Wild West Show, bringing the notion of long flowing locks and also the notion of a last stand to much of the civilized world. Adams’s painting and Becker’s lithograph are among the most famous images to come out of America. They brought the tragedy of the Little Bighorn alive to people not yet born.

George Armstrong Custer usually wore his hair long, but on the day of the famous battle—June 25, 1876—he sported a fresh haircut. The Indian who killed him—there are several candidates—may not immediately have known who they killed. But the women of the Sioux and Cheyenne, who soon came along and pierced Custer’s eardrums with awls because he had disobeyed a perfectly clear warning from the Cheyenne chief Rock Forehead to respect the peace pipe, which Custer had smoked with him, knew exactly who they were working on. They were working on Long Hair, whose hair just didn’t happen to be long on the day he met his death.

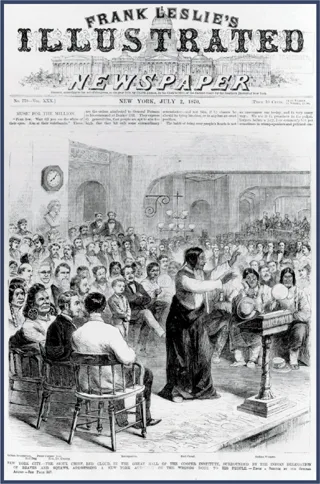

BY 1876, THE YEAR THE Battle of the Little Bighorn was fought, the United States had become a nation of some forty million people, the vast majority of whom had never seen a fighting Indian—not, that is, unless they happened to glimpse one or another of the powerful Indian leaders whom the government periodically paraded through Washington or New York, usually Red Cloud, the powerful Sioux diplomat, who made a long-winded speech at Cooper Union in 1870. Or, it might be Spotted Tail, of the Brulé Sioux; or American Horse, or even, if they were lucky, Sitting Bull, who hated whites, the main exceptions being Annie Oakley, his “Little Sure Shot,” or Buffalo Bill Cody, who once described Sitting Bull as “peevish,” surely the understatement of the century. Sitting Bull often tried to marry Annie Oakley, who was married; he did not succeed.

The main purpose of this parading of Native American leaders—better not call them chiefs, not a title the red man accepted, or cared to use in their tribal life—was to overwhelm the Indians with their tall buildings, large cannon, and teeming masses, so they would realize the futility of further resistance. The Indians saw the point with perfect clarity, but continued to resist anyway. They were fighting for their culture, which was all they had.

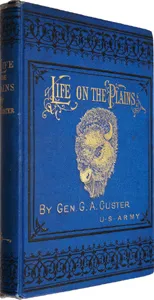

One white who recognized this was the young cavalry officer George Armstrong Custer himself, who, in his flamboyant autobiography, My Life on the Plains, makes this point:

If I were an Indian I think that I would greatly prefer to cast my lot with those of my people who adhered to the free life of the plains rather than to the limits of a reservation, there to be the recipient of the blessed benefits of civilization, with the vices thrown in without stint or measure.

Captain Frederick Benteen, who hated Custer and made no secret of it, called Custer’s book My Lie on the Plains. Yet the book, despite its inaccuracies, is still readable today.

Ulysses S. Grant, who didn’t like Custer either, had this to say about the dreadful loss of life at the Little Bighorn:

I regard Custer’s massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary. . . . He was not to have made the attack before effecting the juncture with Generals Terry and Gibbon. Custer had been notified to meet them, but instead of marching slowly, as his orders required, in order to effect that juncture on the 26th, he entered upon a forced march of eighty-three miles in twenty-four hours, and thus had to meet the Indians alone.

That comment made Custer’s widow, Libbie Custer, an enemy of Grant for life.

Thinking back on a number of important issues, Red Cloud of the Oglala Sioux made this comment: “The Whites made us many promises, more than I can remember,” he said. “But they only kept one. They said they would take our land and they took it.”

RED CLOUD ADDRESSING A NEW YORK AUDIENCE.

Crazy Horse, now thought by many to be the greatest Sioux warrior, refused to go to Washington. He didn’t need to see tall buildings, big cannon, or teeming masses to know that his people’s situation was dire. After the victory at the Little Bighorn the smart Indians all knew that they were playing an endgame. The white leaders—Crook, Miles, Terry, Mackenzie—especially Mackenzie—were even so impolite as to fight in the dead of winter, something they didn’t often do, although the Sioux Indians did wipe out the racist Captain Fetterman and his eighty men on the day of the winter solstice in 1866.

In Texas the so-called Red River War had ended in 1875 and some of its fighting talent, especially Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, went north to help out and did help out.

LINCOLN MEETS CUSTER, OCT. 3, 1862, AT ANTIETAM.

In the East and Midwest, as people became increasingly urbanized or suburbanized, these settled folk developed a huge appetite for stories of Western violence. Reportage suddenly surged; the New York Times and other major papers kept stringers all over the West, to report at once Sitting Bull’s final resistance, or some mischief of Billy the Kid’s or the Earps’ revenge or any other signal violence that might have occurred. Publicity from the frontier helped keep Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show thriving. For a time the railroad bookstores groaned with dime novels describing Western deeds, the bloodier the better. (See Richard Slotkin’s masterpiece The Fatal Environment for a brilliant analysis of how the frontier affected our increasing urbanization.)

By Cody’s day, indeed, the press had the power to make legends, names with an almost worldwide resonance. One of the legends that hasn’t faded was that of the scruffy New Mexico outlaw Bill Bonney (one of several names he used), or Billy the Kid—no angel, it is true, but by no means the most deadly outlaw of his time. That was probably the sociopath John Wesley Hardin.

The other legend that remains very much alive is Custer’s. The Battle of the Little Bighorn is considered by able historians to be one of the most important battles in world history, a claim we’ll deal with in due course.

What Billy the Kid and Custer had in common was fighting; it’s what we remember them for. Both died young, Billy the Kid at twenty-two and Custer at a somewhat weathered thirty-seven. Custer had barely managed to graduate from the military academy (34th out of 34) and then walked right into one of the biggest fights of all time, the American Civil War, a conflict in which 750,000 men lost their lives—warfare on a scale far different from the small-scale range wars that Billy the Kid engaged in.

In the Civil War, Custer’s flair as a cavalry officer was immediately manifest; it found him at war’s end the youngest major general in the U.S. Army. Custer’s ambition, throughout his career, was furthered by the short, brusque General Philip Sheridan, of whom it was said that his head was so lumpy that he had trouble finding a hat that fit.

PHILIP HENRY SHERIDAN.

Not only did Custer have disciplinary problems at West Point, he continued to have disciplinary problems until the moment of his death, June 25, 1876. One thing was for sure: Custer would fight. Time after time his dash and aggression was rewarded, by Sheridan and others.

Ulysses Grant, also a man who would fight, came to distrust Custer—or maybe he just didn’t like him. Grant was never convinced that Custer’s virtues offset his liabilities.

Before the Battle of the Washita (1868), Custer was court-martialed on eight counts, the most serious being his abandonment of his command—he drifted off in search of his wife. He was convicted on all eight counts and put on the shelf for a year; though long before the year was up Sheridan was lobbying to get him back in the saddle.

SHERIDAN WITH CUSTER, THOMAS DEVIN, JAMES FORSYTH, AND WESLEY MERRITT, BY MATTHEW BRADY.

TO SAY THAT THE LITERATURE on Custer—Custerology, Michael Elliott calls it, in a fine book of that name—is large would be to understate by a considerable measure. As a rare book ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- About Larry McMurtry

- Illustration Credits

- Bibliography

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Custer by Larry McMurtry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.