- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A collection of early, emerging works from some of the most celebrated African American female writers who remain strong when the weight of a world filled with racism and gender discrimination wants to drag them down.

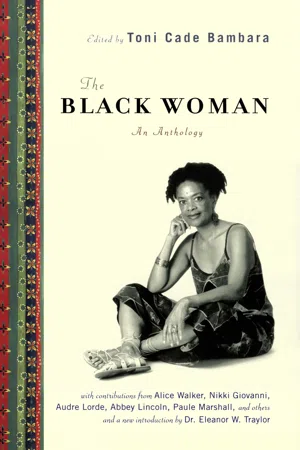

When it was first published in 1970, The Black Woman introduced readers to an astonishing new wave of voices that demanded to be heard. In this groundbreaking volume of original essays, poems, and stories, a chorus of outspoken women—many who would become leaders in their fields, such as bestselling novelist Alice Walker, poets Audre Lorde and Nikki Giovanni, writer Paule Marshall, activist Grace Lee Boggs, and musician Abbey Lincoln among them— tackled issues surrounding race and sex, body image, the economy, politics, labor, and much more. Their words still resonate with truth, relevance, and insight today as the fight for racial and gender equality continues to rage on.

When it was first published in 1970, The Black Woman introduced readers to an astonishing new wave of voices that demanded to be heard. In this groundbreaking volume of original essays, poems, and stories, a chorus of outspoken women—many who would become leaders in their fields, such as bestselling novelist Alice Walker, poets Audre Lorde and Nikki Giovanni, writer Paule Marshall, activist Grace Lee Boggs, and musician Abbey Lincoln among them— tackled issues surrounding race and sex, body image, the economy, politics, labor, and much more. Their words still resonate with truth, relevance, and insight today as the fight for racial and gender equality continues to rage on.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Black Woman by Toni Cade Bambara in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Reena*

Paule Marshall

Like most people with unpleasant childhoods, I am on constant guard against the past—the past being for me the people and places associated with the years I served out my girlhood in Brooklyn. The places no longer matter that much since most of them have vanished. The old grammar school, for instance, P.S. 35 (“Dirty 5’s” we called it and with justification) has been replaced by a low, coldly functional arrangement of glass and Permastone which bears its name but has none of the feel of a school about it. The small, grudgingly lighted stores along Fulton Street, the soda parlor that was like a church with its stained-glass panels in the door and marble floor have given way to those impersonal emporiums, the supermarkets. Our house even, a brownstone relic whose halls smelled comfortingly of dust and lemon oil, the somnolent street upon which it stood, the tall, muscular trees which shaded it were leveled years ago to make way for a city housing project—a stark, graceless warren for the poor. So that now whenever I revisit that old section of Brooklyn and see these new and ugly forms, I feel nothing. I might as well be in a strange city.

But it is another matter with the people of my past, the faces that in their darkness were myriad reflections of mine. Whenever I encounter them at the funeral or wake, the wedding or christening—these ceremonies by which the past reaffirms its hold—my guard drops and memories banished to the rear of the mind rush forward to rout the present. I almost become the child again—anxious and angry, disgracefully diffident.

Reena was one of the people from that time, and a main contributor to my sense of ineffectualness then. She had not done this deliberately. It was just that whenever she talked about herself (and this was not as often as most people) she seemed to be talking about me also. She ruthlessly analyzed herself, sparing herself nothing. Her honesty was so absolute it was a kind of cruelty.

She had not changed, I was to discover on meeting her again after a separation of twenty years. Nor had I really. For although the years had altered our positions (she was no longer the lord and I the lackey) and I could even afford to forgive her now, she still had the ability to disturb me profoundly by dredging to the surface those aspects of myself that I kept buried. This time, as I listened to her talk over the stretch of one long night, she made vivid without knowing it what is perhaps the most critical fact of my existence—that definition of me, of her and millions like us, formulated by others to serve out their fantasies, a definition we have to combat at an unconscionable cost to the self and even use, at times, in order to survive; the cause of so much shame and rage as well as, oddly enough, a source of pride: simply, what it has meant, what it means, to be a Black woman in America.

We met—Reena and myself—at the funeral of her aunt who had been my godmother and whom I had also called aunt, Aunt Vi, and loved, for she and her house had been, respectively, a source of understanding and a place of calm for me as a child. Reena entered the church where the funeral service was being held as though she, not the minister, were coming to officiate, sat down among the immediate family up front, and turned to inspect those behind her. I saw her face then.

It was a good copy of the original. The familiar mold was there, that is, and the configuration of bone beneath the skin was the same despite the slight fleshiness I had never seen there before; her features had even retained their distinctive touches: the positive set to her mouth, the assertive lift to her nose, the same insistent, unsettling eyes which when she was angry became as black as her skin—and this was total, unnerving, and very beautiful. Yet something had happened to her face. It was different despite its sameness. Aging even while it remained enviably young. Time had sketched in, very lightly, the evidence of the twenty years.

As soon as the funeral service was over, I left, hurrying out of the church into the early November night. The wind, already at its winter strength, brought with it the smell of dead leaves and the images of Aunt Vi there in the church, as dead as the leaves—as well as the thought of Reena, whom I would see later at the wake.

Her real name had been Doreen, a standard for girls among West Indians (her mother, like my parents, was from Barbados), but she had changed it to Reena on her twelfth birthday—“As a present to myself”—and had enforced the change on her family by refusing to answer to the old name. “Reena. With two e’s!” she would say and imprint those e’s on your mind with the indelible black of her eyes and a thin threatening finger that was like a quill.

She and I had not been friends through our own choice. Rather, our mothers, who had known each other since childhood, had forced the relationship. And from the beginning, I had been at a disadvantage. For Reena, as early as the age of twelve, had had a quality that was unique, superior, and therefore dangerous. She seemed defined, even then, all of a piece, the raw edges of her adolescence smoothed over; indeed, she seemed to have escaped adolescence altogether and made one dazzling leap from childhood into the very arena of adult life. At thirteen, for instance, she was reading Zola, Hauptmann, Steinbeck, while I was still in the thrall of the Little Minister and Lorna Doone. When I could only barely conceive of the world beyond Brooklyn, she was talking of the Civil War in Spain, lynchings in the South, Hitler in Poland—and talking with the outrage and passion of a revolutionary. I would try, I remember, to console myself with the thought that she was really an adult masquerading as a child, which meant that I could not possibly be her match.

For her part, Reena put up with me and was, by turns, patronizing and impatient. I merely served as the audience before whom she rehearsed her ideas and the yardstick by which she measured her worldliness and knowledge.

“Do you realize that this stupid country supplied Japan with the scrap iron to make the weapons she’s now using against it?” she had shouted at me once.

I had not known that.

Just as she overwhelmed me, she overwhelmed her family, with the result that despite a half-dozen brothers and sisters who consumed quantities of bread and jam whenever they visited us, she behaved like an only child and got away with it. Her father, a gentle man with skin the color of dried tobacco and with the nose Reena had inherited jutting out like a crag from his nondescript face, had come from Georgia and was always making jokes about having married a foreigner—Reena’s mother being from the West Indies. When not joking, he seemed slightly bewildered by his large family and so in awe of Reena that he avoided her. Reena’s mother, a small, dry, formidably Black woman, was less a person to me than the abstract principle of force, power, energy. She was alternately strict and indulgent with Reena and, despite the inconsistency, surprisingly effective.

They lived when I knew them in a cold-water railroad flat above a kosher butcher on Belmont Avenue in Brownsville, some distance from us—and this in itself added to Reena’s exotic quality. For it was a place where Sunday became Saturday, with all the stores open and pushcarts piled with vegetables and yard goods lined up along the curb, a crowded place where people hawked and spat freely in the streaming gutters and the men looked as if they had just stepped from the pages of the Old Testament with their profuse beards and long, black, satin coats.

When Reena was fifteen her family moved to Jamaica in Queens and since, in those days, Jamaica was considered too far away for visiting, our families lost contact and I did not see Reena again until we were both in college and then only once and not to speak to….

I had walked some distance and by the time I got to the wake, which was being held at Aunt Vi’s house, it was well under way. It was a good wake. Aunt Vi would have been pleased. There was plenty to drink, and more than enough to eat, including some Barbadian favorites: coconut bread, pone made with the cassava root, and the little crisp codfish cakes that are so hot with peppers they bring tears to the eyes as you bite into them.

I had missed the beginning, when everyone had probably sat around talking about Aunt Vi and recalling the few events that had distinguished her otherwise undistinguished life. (Someone, I’m sure, had told of the time she had missed the excursion boat to Atlantic City and had held her own private picnic—complete with pigeon peas and rice and fricassee chicken—on the pier at 42nd Street.) By the time I arrived, though, it would have been indiscreet to mention her name, for by then the wake had become—and this would also have pleased her—a celebration of life.

I had had two drinks, one right after the other, and was well into my third when Reena, who must have been upstairs, entered the basement kitchen where I was. She saw me before I had quite seen her, and with a cry that alerted the entire room to her presence and charged the air with her special force, she rushed toward me.

“Hey, I’m the one who was supposed to be the writer, not you! Do you know, I still can’t believe it,” she said, stepping back, her blackness heightened by a white mocking smile. “I read both your books over and over again and I can’t really believe it. My Little Paulie!”

I did not mind. For there was respect and even wonder behind the patronizing words and in her eyes. The old imbalance between us had ended and I was suddenly glad to see her.

I told her so and we both began talking at once, but Reena’s voice overpowered mine, so that all I could do after a time was listen while she discussed my books, and dutifully answer her questions about my personal life.

“And what about you?” I said, almost brutally, at the first chance I got. “What’ve you been up to all this time?”

She got up abruptly. “Good Lord, in here’s noisy as hell. Come on, let’s go upstairs.”

We got fresh drinks and went up to Aunt Vi’s bedroom, where in the soft light from the lamps, the huge Victorian bed and the pink satin bedspread with roses of the same material strewn over its surface looked as if they had never been used. And, in a way, this was true. Aunt Vi had seldom slept in her bed or, for that matter, lived in her house, because in order to pay for it, she had had to work at a sleeping-in job which gave her only Thursdays and every other Sunday off.

Reena sat on the bed, crushing the roses, and I sat on one of the numerous trunks which crowded the room. They contained every dress, coat, hat, and shoe that Aunt Vi had worn since coming to the United States. I again asked Reena what she had been doing over the years.

“Do you want a blow-by-blow account?” she said. But despite the flippancy, she was suddenly serious. And when she began it was clear that she had written out the narrative in her mind many times. The words came too easily, the events, the incidents had been ordered in time, and the meaning of her behavior and of the people with whom she had been involved had been painstakingly analyzed. She talked willingly, with desperation almost. And the words by themselves weren’t enough. She used her hands to give them form and urgency. I became totally involved with her and all that she said. So much so that as the night wore on I was not certain at times whether it was she or I speaking.

From the time her family moved to Jamaica until she was nineteen or so, Reena’s life sounded, from what she told me in the beginning, as ordinary as mine and most of the girls we knew. After high school she had gone on to one of the free city colleges, where she had majored in journalism, worked part-time in the school library, and, surprisingly enough, joined a houseplan. (Even I hadn’t gone that far.) It was an all-Negro club, since there was a tacit understanding that Negro and white girls did not join each other’s houseplans. “Integration, Northern style,” she said, shrugging.

It seems that Reena had had a purpose and a plan in joining the group. “I thought,” she said with a wry smile, “I could get those girls up off their complacent rumps and out doing something about social issues…. I couldn’t get them to budge. I remember after the war when a Negro ex-soldier had his eyes gouged out by a bus driver down South I tried getting them to demonstrate on campus. I talked until I was hoarse, but to no avail. They were too busy planning the annual autumn frolic.”

Her laugh was bitter but forgiving and it ended in a long reflective silence. After which she said quietly, “It wasn’t that they didn’t give a damn. It was just, I suppose, that like most people they didn’t want to get involved to the extent that they might have to stand up and be counted. If it ever came to that. Then another thing. They thought they were safe, special. After all, they had grown up in the North, most of them, and so had escaped the Southern-style prejudice; their parents, like mine, were struggling to put them through college, they could look forward to being tidy little schoolteachers, social workers, and lab technicians. Oh, they were safe!” The sarcasm scored her voice and then abruptly gave way to pity. “Poor things, they weren’t safe, you see, and would never be as long as millions like themselves in Harlem, on Chicago’s South Side, down South, all over the place, were unsafe. I tried to tell them this—and they accused me of being oversensitive. They tried not to listen. But I would have held out and, I’m sure, even brought some of them around eventually if this other business with a silly boy hadn’t happened at the same time….”

Reena told me then about her first, brief, and apparently innocent affair with a boy she had met at one of the houseplan parties. It had ended, she said, when the boy’s parents had met her. “That was it,” she said, and the flat of her hand cut into the air. “He was forbidden to see me. The reason? He couldn’t bring himself to tell me, but I knew. I was too black.

“Naturally, it wasn’t the first time something like that had happened. In fact, you might say that was the theme of my childhood. Because I was dark I was always being plastered with Vaseline so I wouldn’t look ashy. Whenever I had my picture taken they would pile a whitish powder on my face and make the lights so bright I always came out looking ghostly. My mother stopped speaking to any number of people because they said I would have been pretty if I hadn’t been so dark. Like nearly every little black girl, I had my share of dreams of waking up to find myself with long blond curls, blue eyes, and skin like milk. So I should have been prepared. Besides, that boy’s parents were really rejecting themselves in rejecting me.

“Take us”—and her hands, opening in front of my face as she suddenly leaned forward, seemed to offer me the whole of black humanity. “We live surrounded by white images, and white in this world is synonymous with the good, light, beauty, success, so that, despite ourselves sometimes, we run after that whiteness and deny our darkness, which has been made into the symbol of all that is evil and inferior. I wasn’t a person to that boy’s parents, but a symbol of the darkness they were in flight from, so that just as they—that boy, his parents, those silly girls in the houseplan—were running from me, I started running from them….”

It must have been shortly after this happened when I saw Reena at a debate which was being held at my college. She did not see me, since she was one of the speakers and I was merely part of her audience in the crowded auditorium. The topic had something to do with intellectual freedom in the colleges (McCarthyism was coming into vogue then), and aside from a Jewish boy from City College, Reena was the most effective—sharp, provocative, her position the most radical. The others on the panel seemed intimidated not only by the strength and cogency of her argument but by the sheer impact of her blackness in their white midst.

Her color might have been a weapon she used to dazzle and disarm her opponents. And she had highlighted it with the clothes she was wearing: a white dress patterned with large blocks of primary colors I remember (it looked Mexican) and a pair of intricately wrought silver earrings—long and with many little parts which clashed like muted cymbals over the microphone each time she moved her head. She wore her hair cropped short like a boy’s and it was not straightened like mine and the other Negro girls’ in the audience, but left in its coarse natural state: a small forest under which her face emerged in its intense and startling handsomeness. I remember she left the auditorium in triumph that day, surrounded by a noisy entourage from her college—all of them white.

“We were very serious,” she said now, describing the left-wing group she had belonged to then—and there was a defensiveness in her voice which sought to protect them from all censure. “We believed—because we were young, I suppose, and had nothing as yet to risk—that we could do something about the injustices which everyone around us seemed to take for granted. So we picketed and demonstrated and bombarded Washington with our protests, only to have our names added to the Attorney General’s list for all our trouble. We were always standing on street corners handing out leaflets or getting people to sign petitions. We always seemed to pick the coldest days to do that.” Her smile held long after the words had died.

“I, we all, had such a sense of purpose then,” she said softly, and a sadness lay aslant the smile now, darkening it. “We were forever holding meetings, having endless discussions, arguing, shouting, theorizing. And we had fun. Those parties! There was always somebody with a guitar. We were always singing….” Suddenly, she began singing—and her voice was sure, militant, and faintly self-mocking.

“But the banks are made of marble

With a guard at every door

And the vaults are stuffed with silver

That the workers sweated for …”

With a guard at every door

And the vaults are stuffed with silver

That the workers sweated for …”

When she spoke again the words were a sad coda to the song. “Well, as you probably know, things came to an ugly head with McCarthy reigning in Washington, and I was one of the people temporarily suspended from school.”

She broke off and we both waited, the ice in our glasses melted and the drinks gone flat.

“At first, I didn’t mind,” she said finally. “After all, we were right. The fact that they suspended us proved it. Besides, I was in the middle of an affair, a real one this time, and too busy with that to care about anything else.” She paused again, frowning.

“He was white,” she said quickly and glanced at me as though to surprise either shock or disapproval in my face. “We were very involved. At one point—I think just after we had been suspended and he started working—we even thought of getting married. Living in New York, moving in the crowd we did, we might have been able to manage it. But I couldn’t. There were too many complex things going on beneath the surface,” she said, her voice strained by the hopelessness she must have felt then, her hands shaping it in the air between us. “Neither one of us could ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Re Calling the Black Woman by Eleanor W. Traylor

- Preface

- Woman Poem by Nikki Giovanni

- Poem by Kay Lindsey

- Naturally by Audre Lorde

- And What About the Children by Audre Lorde

- Reena by Paule Marshall

- The Diary of an African Nun by Alice Walker

- Tell Martha Not to Moan by Shirley Williams

- Mississippi Politics—A Day in the Life of Ella J. Baker by Joanne Grant

- Motherhood by Joanna Clark

- Dear Black Man by Fran Sanders

- To Whom Will She Cry Rape? by Abbey Lincoln

- The Black Woman as a Woman by Kay Lindsey

- Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female by Frances Beale

- On the Issue of Roles by Toni Cade

- Black Man, My Man, Listen! by Gail Stokes

- Is the Black Male Castrated? by Jean Carey Bond and Patricia Peery

- The Kitchen Crisis by Verta Mae Smart-Grosvenor

- End Racism in Education: A Concerned Parent Speaks by Maude White Katz

- I Fell Off the Roof One Day (A View of the Black University) by Nikki Giovanni

- Black Romanticism by Joyce Green

- Black People and the Victorian Ethos by Gwen Patton

- Black Pride? Some Contradictions by Ann Cook

- The Pill: Genocide or Liberation? by Toni Cade

- The Black Social Workers’ Dilemma by Helen Williams

- Ebony Minds, Black Voices by Adele Jones and Group

- Poor Black Women’s Study Papers by Poor Black Women of Mount Vernon, New York by Pat Robinson and Group

- A Historical and Critical Essay for Black Women in the Cities, June 1969 by Pat Robinson and Group

- The Black Revolution in America by Grace Lee Boggs

- Looking Back by Helen Cade Brehon

- From the Family Notebook by Carole Brown

- Thinking About the Play by The Great White Hope Toni Cade

- Are the Revolutionary Techniques Employed in The Battle of Algiers Applicable to Harlem? by Francee Covington

- Notes on the Contributors

- Bibliography

- Copyright