![]()

CHAPTER ONE

“You Meet a Gentleman”

HIS REAL NAME WAS JOHN PAUL, inherited, along with a chip on the shoulder, from his father. John Paul Sr. was a proud and talented man. Today, he would be called a landscape architect. In eighteenth-century Scotland, he was a gardener. He had been hired—indeed, recruited all the way from Leith on Scotland’s east coast—to lay out the gardens at Arbigland, a 1,400-acre estate in the soft and wildly beautiful countryside that rims the Firth of Solway, the body of water that divides England and Scotland on Britain’s west coast. John Paul Sr.’s profession was at a kind of apex: the mid-eighteenth century was a great age of landscape gardening. Abandoning the constrained formalism of the Continent, English landscape gardeners like Capability Brown created romantic vistas, ponds, glades, groves, hillocks, and glens and dales for the local gentry who hired them. At Arbigland, Paul Sr. turned nature’s gifts into murmurring brooks and fragrant ponds with lily pads and gently overhanging willows. Luxuriant flowers and Mage spilled across mossy paths that wound through a sweet-smelling wonderland. As a little boy, John Paul Jr. wandered in a man-made enchanted forest that would suddenly and breathtakingly open to the sea. Walking through the gardens John Paul Sr. laid out more than two centuries ago, it is easy to understand how John Paul Jr. formed the softer sensibility that inspired the romantic poetry and “fine feelings” he espoused.

John Paul Sr. was a manager as well as an artist. The household staff at Arbigland was enormous, over a hundred maids, grooms, cooks, gamekeepers, and gardeners, and as head gardener Paul Senior’s rank roughly equaled that of head butler. But he was still a member of the servant class, required to tip his forelock to his master, Mr. Craik. The world was still stratified in 1750. Each man was supposed to know where he stood in the Great Chain of Being, the immutable social order, fixed by God. (If he didn’t, notes historian Gordon Wood, there were guidebooks. Young George Washington, growing up in the colony of Virginia, copied out instructions on how to pull off one’s hat to “Persons of Distinction” and how to bow “according to the custom of the better bred and quality of the person” in order to “give every person his due title according to his degree.”) The Scottish lived with another level of subservience. From time to time, English kings subdued Scottish uprisings. One of the most storied rebellions was crushed about a year before young John Paul was born. In April 1746, on Culloden Moor, an English army defeated the forces of Charles Edward Stuart, “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” Jacobite pretender to the crown.

William Craik, the master of Arbigland and John Paul’s employer, was not a Jacobite. He cast his lot with the ruling English. Craik was a domineering figure, “ardent to make himself completely master of whatever he took in hand,” according to his daughter, Helen. He understood Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, and Italian; he made “some little progress in Spanish,” was a “tolerable architect,” “fond of chemistry,” and “read much on learned subjects.” He had been a willful hell-raiser as a young man. “In hard drinking, hard riding, and every other youthful excess, few could equal his notoriety,” wrote his daughter. And he was a hard man who brooked no disrespect or dissent. Social tensions ran high on Scottish estates after landlords began driving tenants off the land in the early eighteenth century. There were riots as “levelers” fought back. Craik ordered his tenants to conform to the new rules of agriculture or face jail instead. Toward his gardener Craik was more respectful, but John Paul was supposed to do what he was told.

John Paul bristled against Craik’s overbearing authority, but he did so quietly, using an edge of sarcasm to undercut his deference. His sullenness showed in an odd way. Symmetry in architecture was all the fashion in the mid-eighteenth century. It appears that Craik, who was building a manor house in the classical style, insisted on building not one but two summer houses in the garden. John Paul, raised a frugal Scotsman, thought the second summer house was extravagant, a point he made in peculiarly subversive fashion. Upon catching a man stealing fruit, John Paul Sr. locked him in one of the summer houses. Then he locked his little boy John Jr. into the other summer house. Craik found this peculiar, and asked why the boy had been locked up. John Paul Sr. drily replied in his brogue, “for the sake of symmetry.”

John Paul Sr. may have resented more than his laird’s extravagance. For many years after John Paul Jones became famous as an American navy captain, it was rumored in Kirkbean and the small towns around Arbigland that John Paul Jr. was really the bastard son of William Craik. It is true that John Paul’s mother, Jean McDuff, worked as a housekeeper for Mr. Craik. She married John Paul Sr. the day before Craik married a neighboring lady, a coincidence that raised eyebrows in the village. Scottish lairds not uncommonly enjoyed sexual favors from the household help and sometimes had the progeny to show for it. Craik did have at least one illegitimate son (interestingly, in later life he became George Washington’s personal physician). Was young John another? John honored his nominal father. He had built in the Kirkbean graveyard a large crypt, inscribed “John Paul Senior who died at Arbigland the 24 October 1767 Universally Esteemed. Erected by John Paul Junior.” But he may have questioned his parentage. A sensitive boy, he could not have missed the tension between his proud father and the lordly Mr. Craik, especially when he was sitting locked in the summer house, wondering why he had been put there. John Paul Jr. observed his father’s seethings and vowed not to cringe himself. John Paul Jones’s sense of resentment and wounded pride were never far from the surface in later life. He came by them naturally.

From the day of his birth, July 6, 1747, John Paul Jr. lived with his brother, three sisters, and both parents in a tidy, two-room cottage. Cramped and stuffy inside, it overlooked a magnificent vista, a field running down to the Firth of Solway. Playing along the shore, with its pungent salty smell, John Paul Jr. could imagine Viking ancestors who had landed there centuries before. On clear days, he could see across to the English coast and the mountains of the Lake District. On most days of his childhood, he could watch the great ships slipping down the firth to the Irish Sea beyond, bound for distant lands.

Young John was an eager, bossy boy. Mr. Craik’s son Robert recalled watching John Paul Jr. standing high on a rock at the edge of the shore, yelling orders at his playmates in a shrill voice as they paddled about in rowboats. He was pretending to be a fleet admiral, staging a sea battle. John Paul turned twelve years old in the “Glorious Year” of 1759 when the Royal Navy under Admiral Hawke defeated the French at Quiberon Bay on the Brittany Peninsula. Hawke’s flagship captain, John Campbell, hailed from Kirkbean, a small town just outside the gates of Arbigland, where John Paul attended the parish school. He heard the story of how Admiral Hawke sent the British fleet tearing in after the French, ignoring the danger of a lee shore on a stormy day, ordering his captains not to open fire until they were, as close range was then commonly measured, “within pistol shot.”

John Paul wanted to join the Royal Navy. “I had made the art of war at sea in some degree my study, and had been fond of the navy, from boyish days up,” he wrote Benjamin Franklin many years later. The navy could be a social ladder for some poor boys. Captain James Cooke, the great South Sea explorer, had been a laborer’s son, and Horatio Nelson was born in a modest parsonage. But entering the navy’s officer class by obtaining a midshipman’s berth—as a “young gentleman”—usually required the right social connections. The Pauls had none. The best John Paul Jr. could do was sign on as an apprentice aboard a merchant ship. John Paul could hope—after seven years of servitude—to rise above the level of an ordinary seaman. But the social prestige and chance of glory for a first mate or even a master aboard a merchantman did not approach that of a naval officer. Jones swallowed his disappointment at not winning a naval commission, but not his ambition.

Young boys sometimes catch sea fever. In the eighteenth century, many boys went to sea by the age of thirteen. If they waited any longer, the philosopher of the age, Dr. Johnson, once observed, they wouldn’t go. No right-minded adult would volunteer to go to sea. Shipboard life was too awful.

In 1760, when John Paul turned thirteen, he boarded a two-masted brig out of Whitehaven, a British port across the Solway (where he would return eighteen years later as an American naval officer, intending to burn the place). The Friendship was about eighty feet long and could carry less than 200 tons; she would barely qualify as a “tall ship” today. In the wintery Irish Sea, she rolled and tossed enough to send all but the hardiest of her crew leaning over the leeward rail to vomit. Melville called seasickness “that dreadful thing.” Abigail Adams described it as “that most disheartening, dispiriting malady…. No person, who is a stranger to the sea, can form an adequate idea of the debility occasioned by sea-sickness.” Imagine being extemely drunk and hung over all at once and you have some idea: whirling, reeling, nauseous distress and lassitude.

Winter storms in the Atlantic would terrify even the bravest boy. Mountainous seas could lay a small ship over on her beam ends and tear the sails from her spars. A wooden ship rigged with rope and canvas is like a living organism: it creaks and sighs and groans. In a gale, it screams.

Belowdecks in all weathers, the ship stank from unwashed men and bilge-water. While the men were supposed to relieve themselves at the head, no more than a hole in the deck off the bow of the ship, in bad weather and illness they sometimes defecated, urinated, and vomited where they stood or slept. The water that collected in the bilge, full of excrement and rot of one kind or another, was unspeakable. In the abundance of Arbigland, John Paul had milk, butter, fresh vegetables. Aboard the Friendship, he dined on salt beef, dried peas, and biscuit, day after day. The beef, pickled in brine, savored vaguely of fish, and the biscuits were so full of weevils that they moved. The peas were like bullets; the butter, when it wasn’t rancid, tasted like oil sludge. The water, carefully rationed (no bathing—saltwater had to do) was covered with a coat of slime after a few weeks. The damp was inescapable: wool clothes, caked with salt, held moisture for days.

Like everyone else, young John Paul was given a ration of alcohol. Typically, seamen were allowed a half pint of rum or a half gallon of beer a day (or a pint of red wine, which they disdained and called “black strap”). Four ounces of rum, served twice a day cut with water and made into “grog,” was a pretty powerful cocktail. And naturally, the men hoarded and stole rations and smuggled liquor aboard to get drunker. Drunkenness was the number one cause of discipline problems and no small cause of accidents. A slightly tipsy—or “groggy”—man could miss a step as he climbed the rigging or lose his footing as he edged out along a spar.

John Paul didn’t develop a taste for grog. In all his years at sea, he never touched hard spirits. His “steady drink,” recalled one of his midshipmen, was lemon or lime juice laced with sugar and, in good weather, three glasses of wine after dinner. He liked to be in control of himself and, insofar as possible, his world. Too many times he had witnessed the damage caused by indulgence.

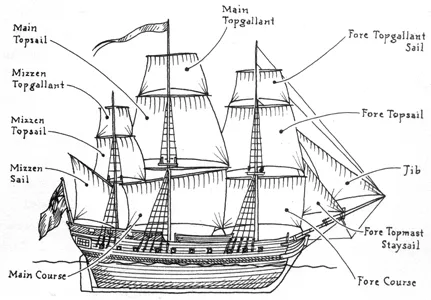

Like all new hands on a square-rigged ship, John Paul was sent aloft to learn how to reef and furl the sails. Creeping out along a single rope far above the deck and leaning over to gather wet and sometimes frozen canvas flailing and snapping in the wind was not for the fainthearted. Anyone who has climbed a mast on a ship as it rolls and bucks at sea can attest to a frightening law of physics: the higher you go, the wider (and wilder) the swings. Men, especially the inebriated ones, often fell. If they were unlucky, they hit the deck and shattered bones and skulls. If they were more fortunate, they glanced off a rope or the belly of a sail and landed in the ocean. Some were rescued in time, but a large, square-rigged sailing ship is cumbersome to turn around, and ocean water temperature in the northern latitudes could freeze a man in a few minutes. Many drowned because they could not swim; few seamen in those days could.

Some men fell from sheer exhaustion. The Friendship carried a crew of twenty-eight, large for a merchantman but far fewer than the ship’s company aboard a man-of-war of comparable size. Merchants tried to squeeze every last penny out of their ships. Carrying the bare minimum of crewmen and stinting on food were standard practices in the merchant marine. Aside from a large winch, called a capstan, and various blocks and pulleys to take off some of the strain, eighteenth-century sailing ships relied on brute man power. The work could be perilous: men had to haul on rigid and icy ropes as they slipped and slid on slanting and shifting decks, in storms and rain and in utter darkness. The most common medical hazard was hernia, or rupture. (During the eight years from 1808 through 1815, the Royal Navy handed out an amazing 29,712 trusses.) It has been estimated that about one in seven British seamen in the navy busted a gut, literally.

Misery excited John Paul’s ambition. The position of master or first or second mate aboard a merchantman may not have been nearly so grand as that of a naval officer, but it was better than ordinary seaman, in part because the first or second mate was rarely required to work aloft or heave on a rope.

John Paul’s deliverance from the hardship of the lower deck was a brass instrument called an octant. His ascent began the moment the master of the Friendship, Captain Robert Benson, summoned him to the rail of the quarterdeck one day when the sun was at its zenith, pointed to the horizon, and handed him the tool navigators used to find their way on the trackless sea.

Jones’s own octant, possibly his very first, sits in the museum of the U.S. Naval Academy. Curved (an eighth of circle, hence “octant”), fixed with small mirrors and etched by degrees, an octant can tell a mariner the angle of the sun to the horizon at high noon. From these readings, taken repeatedly for accuracy, a mariner who knows a little math and has the right tables can calculate his ship’s latitude, his distance from the equator. Navigation was still crude in the mid-eighteenth century. Navigators could fix their place on a north-south axis by knowing their latitude (at least when the sun was not clouded over), but they still couldn’t precisely measure longitude, their position along the east-west axis. Finding one’s way was still to a frightening degree a matter of guesswork—dead reckoning.

And yet elemental navigation was considered sorcery in the wrong hands. A sailor who could navigate made a much more dangerous mutineer. In the navy, the officer class did not want ordinary seamen to be able to find their way if they mutinied. The merchant marine was not quite so fearful about sailors rising above their station. As an apprentice, John Paul could entertain some hope of learning the skills required of a deck officer, though perhaps not right away, since his apprenticeship was expected to last seven years. A quick learner, eager to please, he apparently won the attention and support of the master, Captain Benson.* Before long, he was mastering all the intricacies of seamanship and ship handling, the proper set and trim of the sails, the uses of all the myriad ropes and spars that festooned the masts of a square-rigged ship.

He accomplished his tasks efficiently and surely but not joyously. John Paul was a self-described romantic, but not about the sea. He did not wax on about the beauty or mystery or power of the oceans, except in one batch of letters written after a particularly fearsome storm, and then only to comment that “the awful majesty of the tempest … surpassed the reach even of poetic fancy and the pencil.” If John Paul was touched or awed by the majesty of nature on his first cruises across the ocean, he failed to record those feelings. His greater concern was with self-improvement.

John Paul discovered aboard ship a place to excel. In any age, seamanship demands certain qualities of character. It rewards the careful and deliberate and punishes the loose and sloppy. The uncoiled line lying about the deck can quickly be transformed into a snare or a whip in bad weather; the sleepy lookout nodding off as the ship approaches a hidden reef is criminally negligent. In his manner and bearing, John Paul was neat to the point of primness. As a sailor he was constantly, almost exasperatingly, fastidious, incessantly fiddling with the rigging and trim to eke out more speed and make his craft more seaworthy. He may not have loved the sea, but he was very good at sailing upon it.

JONES HAD TO stoop low to climb up. In 1764, after he had crossed the Atlantic eight times in three years aboard the Friendship, hard times forced the sale of the ship. Released from his apprenticeship, he found a wretched job as the third mate aboard a slaver, the King George, out of Whitehaven, a “black birder” in the cruel jargon of the time. Black birders were known for a stench so strong that ships downwind bore away to avoid it. John Paul served for two years aboard the King George and was made first mate of another slave ship, the Two Friends. No more than fifty feet long, she carried a crew of six and, chained in the hold, according to one manifest, a cargo of “77 Negroes from Africa.” John Paul sailed the infamous “middle passage” between Africa and the slave plantations of the Caribbean. “Slaves were stowed, heel and point, like logs,” Melville wrote, “and the suffocated and dead were unmanacled, and weeded out from the living every morning.” John Paul Jones never wrote a word about his time on a slave ship, but after three years he had apparently had enough of duties like “weeding.” When the Two Friends returned to Jamaica from a voyage to “the windward coast of Africa” sometime in 1767, John Paul asked to be paid off.

In Kingston, the unemployed John Paul ran into the captain of a brig, the John, out of Kirkcudbright, a small Scottish port some thirty miles from Arbigland. The captain, Samuel McAdam, offered John Paul free passage home. On the voyage, both the captain and the first mate died of fever, which was rampant in the West Indies. John Paul was the only man aboard who could navigate. When he brought home the John safely, the owners rewarded him with command. At the age of twenty-one, he was the master of a ship. A very small one, to be sure: sixty tons, about sixty feet long, with a crew of half a dozen men. But John Paul had crossed the line from servant to master.

John Paul was not an easy captain. He was fastidious and demanding. His standards of neatness and precision were closer to those aboard a man-of-war than on a merchant ship. His rigor and exactitude did not necessarily make him unpopular with the crew. The hands of a square-rigged ship, a fragile and complex mechanism, depended on their captain to survive. They usually distrusted captains who were slack or sloppy. Taut ships were happy ones if every man knew his duty and the captain showed steadiness and good seamanship. Captain Paul was a superb seaman whose confidence seemed to rise in dangerous moments, and he was usually mild and soft-spoken. But there was a scratchy, fussy side to him that was off-putting and which, over time, worked to undermine his authority. Jones had a temper, and he could not abide disrespect. He was bound to clash with sailors who did not know their place or challenged his.

On John Paul’s second voyage aboard the John, from Scotland to the Windward Islands, he tangled with a carpenter’s mate named Mungo Maxwell. The son of a prominent local family in Kirkcudbright, the John’s home port on the Firth of Solway on Scotland’s southern coast, Maxwell wa...