![]()

Preface

If you were in the common crotch, a grunt U.S. Marine, you went where you were told, did what you were told, and tried in the process to keep your butt from getting shot off. The brass back at Division or somewhere higher up moved your colored pin from place to place on the map and you simply followed it. You rarely saw the “Big Picture.” What you saw of the war was what there was of it in your immediate vicinity.

Right now, what we saw of it—PFC James McKinney and I, Lance Corporal Raymond Hildreth—wasn’t much. What we saw of anything wasn’t much. McKinney and I hunkered shoulder to shoulder on the eastern slope of Hill 488. It was so dark that if I scratched my nuts I had to ask James if they were mine or his I was scratching. Vietnam defined the word dark.

Breezes rustled surreptitiously through the wheatlike grass fields that covered the hill, making little whispering sighs like predators passing in the night.

“Daylight belongs to us,” Lance Corporal Osorio explained when I first arrived in-country. “The dark belongs to them.”

As far as McKinney and I were concerned, we could have been on another planet twenty-five million miles away from Chu Lai instead of a mere twenty-five. Darkness hid danger while at the same time providing a false security that it also hid you from danger.

“Ray?” McKinney whispered, nudging me.

“Yeah. I’m awake.” Sergeant Howard had placed the platoon on fifty percent alert at dusk, which meant one of us could sleep.

“Reckon there’s still a world out there?”

McKinney was a bit of a pessimist.

“The world is what you can see, James.”

“It’s a small world, Ray. I can’t even see my feet.”

He edged closer. Our knees touched. Touching another human being provided a great deal of comfort when you were two nineteen-year-olds in the dark a long way from home and surrounded by people who wanted to kill you. We talked for a while, whispering about home and family and girls and cars. After awhile, McKinney pulled a poncho over his head so the glow wouldn’t be seen while he smoked a cigarette. He yawned and nestled down under his poncho, saying he was going to catch a few Z’s.

“Wake me in a couple of hours and I’ll let you grab some rack time,” he said.

He was soon breathing deep and regular. I repositioned my M-14 across my legs. Corporal Jerald Thompson, Squad Leader, slipped down the hillside and dropped on one knee next to us. We were about twenty meters off the crest of the hill where Sergeant Howard had established his command post behind a boulder about the size of a VW with the top chopped off. The rest of the platoon, also in pairs, formed a three-sixty degree perimeter around the top of the hill.

Thompson hissed, “You guys awake?”

“Yeah,” I said.

McKinney stirred and leaned against me in his sleep, like a little brother. It had been a long day.

“Sergeant Howard has put us on one hundred percent alert. Hildreth, move over to your right about twenty meters.”

“What’s up?” Something cold and slimy stirred inside my guts.

“There’s been lots of movement,” Thompson whispered. “One of the other Recons had to be pulled out. If we have to bug out, Hildreth, you’re point man. Lead us down that draw in front and then around to the right. Got it?”

“Yeah.”

He followed to check my new position. I settled down in the tall grass with my rifle, pack and ammo belt.

“Remember to fire underneath the muzzle flashes,” he said before he moved on to pass the word.

A shiver skittered up my spine and prickled the short hairs on my neck. Folks back in Oklahoma said you got a shiver like that whenever someone walked over your future grave.

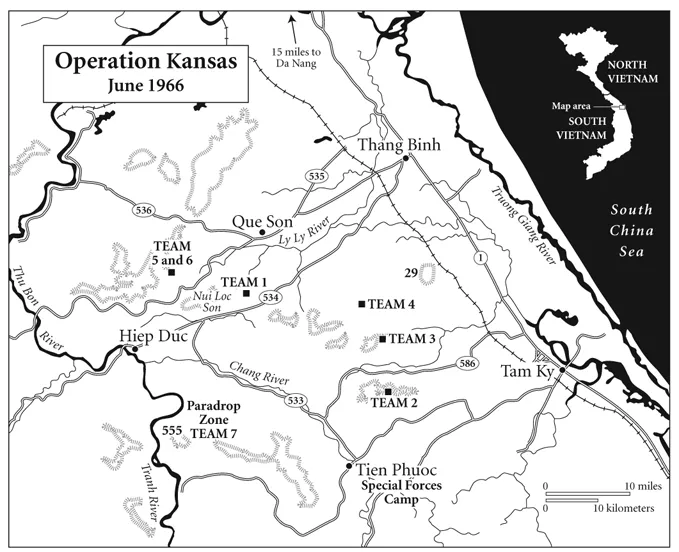

Team 2, Sergeant Howard’s recon team, was inserted on Nui Vu Hill on 13 June at the beginning of Operation Kansas. This map shows the locations of the other reconnaissance teams of the First Recon Battalion and the locations of their insertions. Sergeant Howard’s First Platoon received artillery support from the Tien Phuoc Special Forces camp approximately five miles to the south.

Part I

Accursed be he that first invented war.

MARLOWE

![]()

1

My dad was fifty years old and working on his second wife when I was born. I had two brothers and a half-sister, but they were so much older that it was like I was an only child. Mom died when I was fifteen, which left Dad and me bacheloring it together in the rough neighborhoods of North Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was an old man by the time I reached high school. He hadn’t the energy to ride herd on a rebellious teenager. I started running with a bad crowd at Rogers High School. Some might have said I was the bad crowd. Whichever, the cops picked me up for burglarizing a vending machine two months before graduation. That was in March 1965. A couple of other guys and I were popping Laundromat soap boxes and rifling the machines for coins.

I was seventeen and therefore no longer a juvenile, according to Oklahoma law. I went to the big boy’s jail at the County Courthouse downtown. Talk about a hollow feeling when that steel door clanged behind my punk ass. I shook all over. It reminded me that I wasn’t that stud I thought I was.

Dad left me behind bars for four days to think things over before he showed up to get me out. I did a lot of thinking too. Here I was four months from being out on my own, from being an independent adult, and I was already on my way to prison.

“You’re heading down a bad road, son,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“So what are you going to do about it?”

“Go in the Marines—if they’ll still have me.”

Like I said, I had been doing a lot of thinking. I had wanted to be a Marine as far back as I could recall. My infatuation with the Marine Corps began after I watched an old Wallace Beery movie set during World War II. Marines were the fightingest, baddest warriors on land or sea anywhere in the world. It took a real man to wear the Marine Corps uniform.

“What are you going to do when you get out of school?” friends asked.

“Join the Marine Corps,” I automatically responded.

Well, it was time to put up or shut up. Dad nodded in that slow way of his. The Marines were honest and honorable, and they knew how to jerk the kink out of a bad boy’s tail.

“Dad?”

Dad walked away. He left me in jail one more day just for good measure. My half-brother Homer, a retired Tulsa police detective, talked him into getting me out. By the time he made my bail, I could hardly wait to run down to the nearest recruiting station. I had embarrassed my dad and embarrassed myself, but surely I could redeem myself in the Marines.

I received a deferred sentence and probation on the condition that I enlist in the Marines, if they would have me. I signed up on the delayed entry program along with a couple of high school buddies, Gary Montouri and Stephen Barnhart, which meant we were allowed to graduate from high school before shipping out to boot camp. That day I raised my hand and swore loyalty and obedience to God, country, and the Marine Corps, not necessarily in that order, and promised to rain fire and brimstone upon all enemies happened to be only two weeks after the buildup of troops began in Vietnam with the landing of the Ninth Marine Expeditionary Brigade at Da Nang on 9 March 1965.

Still, at that time, Vietnam was little more than a once-a-week footnote on NBC News. Vietnam was a long way off. Most people, including me, couldn’t have picked it out on a map. I was little aware of how the situation was rapidly eroding and becoming a real war.

Things changed even more from March to July, the month I actually packed my bags and left for Oklahoma City to catch my first airplane ride to the United States Marine Corps Recruit Training Depot in San Diego, California. Viet Cong sappers crept onto the air base at Da Nang and destroyed three aircraft and wounded three Marines. Three Marines were killed and four wounded in a firefight at Duong Son. Lieutenant Frank S. Reasoner became the first Marine in South Vietnam to win the Congressional Medal of Honor, posthumously.

Walter Cronkite, “the most trusted man in America,” was now talking about the war every night on the news. Friends asked me if I weren’t afraid of going. Nah. There were already enough Marines in Vietnam to handle the job without adding me to the number. I could wear the good-looking uniform and have the name without the game. Besides, when you were a strapping eighteen-year-old kid a couple of inches under six feet tall and full of yourself, you thought you were going to live forever.

What I couldn’t know at the time was that 1965, the year I completed Marine Corps training, would be a year of bloody fighting in the highlands between Chu Lai and Ban Me Thout—and that I would be personally involved in the strategy of attrition announced by General William West-moreland, Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). That strategy, simply put, stated that we would kill more of them than they killed of us.

“We’ll just go on bleeding them until Hanoi wakes up to the fact that they have bled their country to the point of national disaster for generations,” he said.

That was the beginning of the practice of counting dead bodies, the all-important “body count,” to keep track of how well we were doing.

My half-brother Homer saw it coming. He was a lot older than me, and a veteran of World War II as well as a retired cop. He came back from the war as a colonel with a chest full of medals.

“Don’t try to be a hero,” he counseled when I came home for boot camp leave. “Don’t take any chances. Don’t think. Act on your instincts. Expect the unexpected and always be on the alert.”

It didn’t take a rocket scientist to understand that the aim of Marine Corps boot camp was to emotionally strip us of our individualities and mold us back into a single functioning combat unit. A mean, lean, green fighting machine. Generations of scraggly, undisciplined youth from across the country had undergone that traumatic metamorphosis from civilian to warrior the Marine way. It started the moment the bus from the airport pulled into the Receiving Depot in San Diego and that hard hunk of mean in the drill instructor hat let you know immediately who was in charge and that you had better jump through your ass to please him.

“All right, ladies,” he growled in a way that you knew his bite was worse than his bark. “You puke maggot pussies shut your meat traps and listen. Get off my bus and get off it now. You got five seconds, or your ass is mine.”

I was off in three flat.

“That was slow, that was sloppy, your breath stinks, and you don’t love Jesus. You goofy-looking maggots are gonna have to do better than that. Get with the program, pussies. Get on those yellow footsteps. Don’t speak unless you’re spoken to. The first word out of your mouth is ‘sir,’ and the last word out of your mouth is ‘sir.’ Is that understood, ladies?”

It was a clusterfuck of responses. The DI liaison went bugfuck, red in the face. “What?”

I had never heard someone so proficient in the art of profanity.

“What part of that didn’t you cunts understand? Let’s hear it again, the right way. Is that understood, ladies?”

“Sir, yes, sir.” More or less in unison.

“I can’t hear you …”

Bellowing it out. “Sir, yes, sir!”

“You fucking dickheads will never be Marines.”

I was in total shock for the first five days. Scared to hell. Every DI—you called them drill instructors to their faces, as they said DI stood for damned idiot, which they weren’t— looked capable of taking on Man Mountain Dean and whipping his ass in the ring. I didn’t sleep at all the first night. DI’s yelled at us constantly. They expected us to obey and react instantly.

“You pussies gonna sleep all day?” It was still the middle of the night. “Get your asses out of them fart sacks …”

“You’re getting your haircuts. Don’t speak. If you got a mole or something, point to it, but keep your mouths shut …”

“Boot! What was that? Were you talking about my mother? I love my mother. Get down. Get down! Give me twenty pushups and every time your chest hits the ground I want to hear it …”

First, they tore you down. Then they built you back up. The Marine way.

All through basic training, DI’s underplayed and understated the actual war element of the drills while stressing the mechanics of it. For all that Vietnam loomed over our shaved heads like a prophetic specter, for all that our eyes popped suddenly open at night looking into the ghost world of times to come, none of us actually believed we would go.

One afternoon on the firing range, a DI brought in a photo clipping from a newspaper. It showed a dead U.S. Marine lying on his back clutching a bloodstained bayonet across his chest. The picture made its silent way through the ranks. Everyone stared at it and swallowed. This dead guy wasn’t much older than any of us, if at all. The war that seemed so far away suddenly became a lot closer. Something queasy stirred in the pit of my stomach, seriously disturbing my sense of immortality.

“If you guys don’t pay attention in boot camp,” the DI said, “this guy could be any of you.”

I paid attention, but I paid more attention after that. My forte was the ability to shoot a rifle. I had been on the rifle team at Rogers High School. The recruit who fired the highest score received an automatic promotion to PFC, private first class. I fired expert, a 224, but I missed getting the promotion by one point. The score was high enough, however, as I found out later, to qualify me to attend Marine sniper school.

After twelve weeks of basic, Recruit Training Platoon 345 graduated fit, tanned, tough, and full of ourselves. Automatically, we were no longer “boots,” “shitheads,” “maggots,” or “pussies.”

“Today, you are United States Marines.”

Jesus, I stood tall, addressed like that for the first time. Semper fi and all that. Hey, I could eat the enemy for breakfast and still devour a platter of eggs, bacon, and SOS prepared by other by-God United States Marines. Dad was going to be proud of me. I looked forward to going on boot leave and strutting my stuff around Rogers High in my uniform. Watch out, girls.

The commander summoned a formation to read off our next duty assignments. He called us off alphabetically, followed by the duty station. I couldn’t help noticing that about every other man was being sent to the Third Marine Replacement Company. Replacement for whom?

The alphabet reached me. “Hildreth, Raymond Stanley: Third Replacement.”

Afterward, the commander explained. “For those of you assigned to the Replacement Company, that’s a stop-off point in Okinawa. Congratulations. It means you’re going to Vietnam.”

![]()

2

Vietnam? The war no longer seemed quite so unreal. Still, when you were eighteen years old, about the only reference point you could hang war on was Sands of Iwo Jima or To Hell and Back. The substance of war was a slippery concept to grasp. I thought about it and understood the words, but the reality occupied a much more incomprehensible elevation. After all, this time last year I was going to high school football games at Skelly Stadium and chasing cheerleaders on the Restless Ribbon.

The concept continued to become more tangible, however. Following ITR, Infantry Training Regiment, a kind of advanced boot camp, and a thirty-day leave, those of us with pending orders to the Third Replacement Company were assigned to Camp Pendleton’s Staging Battalion. Staging, as in staging for war.

A full Vietnamese village, complete with thatched-roof mud huts, pig pens, bamboo fences, and narrow booby-trapped trails through jungle growth expelled any lingering doubts I might have harbored about my not being needed personally for the war effort. For a week we trained hard in jungle warfare, booby traps, small unit actions, escape and evasion, survival, and underwent orientation about the country and the people and why the United States was involved.

I learned to respect and fear the enemy before I ever saw him. The Viet Cong, or VC, we were assured, were formidable infantry opponents. Vietnam bred fighters, women and children as well as men. After all, generations of Vietnamese had cut their first teeth on war. Fathers, uncles, older brothers, grandfathers, and great grandfathers, had fought the Japanese, the French, Saigon’s troops, and now the Americans. For a thousand years before that, they had fought the Chinese, Cambodians, Thais, and anyone else who attempted to invade their rich lands. Generations past remembered little but wars interspersed ...