![]()

THE UNITED STATES

![]()

Commentary and Notes on References

WHEN THE MOORS were expelled from Spain, they returned to Morocco, where the emperor El Mansur arranged with them to invade Equatorial Africa, the old empire of Songhay. This invasion broke up the structure of the last great empire in Western Africa. And the chaos that followed set up Africa for the future European slave trade.

The slave trade prospered, and Africans continued to be poured into the New World. Figures on the subject vary, but it has been established that during the years of the African slave trade, Africa lost from 60 to 100 million people. This was the greatest single crime ever committed against a people in world history. It was also the most tragic act of protracted genocide.

The first Africans who came to the New World were not in bondage, contrary to popular belief. Africans participated in some of the early expeditions, mainly with Spanish explorers. The best-known of these African explorers was Estevanico, sometimes known as Little Steven, who accompanied the de Vaca expedition during six years of wandering from Florida to Mexico.

There existed in Africa prior to the beginning of the slave trade a cultural way of life that in many ways was equal, if not superior, to many of the cultures then existing in Europe. And the slave trade destroyed these cultures and created a dilemma that the African has not been able to extricate himself from to this day.

There were in the Africans’ past, rulers who extended kingdoms into empires, great armies that subdued entire nations, generals who advanced the technique of military science, scholars with wisdom and foresight, and priests who told of gods that were kind and strong. But with the bringing of the African to the New World, every effort was made to destroy his memory of ever having been part of a free and intelligent people.

In the United States, in the fight to destroy every element of culture of the slaves, the system was cruel. No other system did so much to demean the personality of the slave, to deny his personality, or to ruthlessly sell family members apart from each other. The American slave system operated almost like the American brokerage system. If a person bought twenty slaves at the beginning of the week, and found himself short of cash at the end of the week, he might, if the price was right, sell ten. These ten might be resold within a few days. The family, the most meaningful entity in African life, was systematically and deliberately destroyed.

The publication of William Styron’s novel The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967) and the dissenting reactions of a number of black writers that were published in the book William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond (1968) has caused new interest in the life of Nat Turner and slave revolts in general. In addition to the two books already mentioned, Herbert Aptheker’s Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion (1966) provides new insight into the most famous of all the American slave revolts. The roots of these revolts are deep in the history of this country.

In the United States, especially during the American Revolution, the African slave often took the place of a white person who decided that he did not want to fight, and fought with the promise that he would get freedom afterward. Thousands of Africans fought in the American Revolution with this promise. And a little-known incident in our history is that thousands of Africans fought with the British when the British made the same promise and the African believed them. Apparently it depended on who got to him first.

The African was a major contributor in the making of the New World; the economy of the New World rested largely on slave labor. For many years one-third of the trade of the New World was with the small island of Santo Domingo, which later became Haiti. Haiti and the other Caribbean islands also influenced the economic system of Europe.

The first large-scale intercontinental investment of capital was in slavery and the slave trade. Many Europeans invested in ships and in the goods and services taken from these African countries and thus became independently wealthy.

But the slave revolts continued. By the end of the seventeenth century, the picture of slavery began to change drastically. Economic necessity, not racial prejudice, originally directed the African slave trade to the New World. As early as 1663 a group of white indentured servants rose in revolt. And some slaves took the Christian version of the Bible literally and believed that God meant for them to be free men’slaves such as Gabriel Prasser in Virginia, who led a revolt of 40,000 slaves in 1800. In 1822 in Charleston, South Carolina, a carpenter, Denmark Vesey, planned one of the most extensive slave revolts on record, but he was betrayed and put to death with many of his followers. And in 1831 Nat Turner led the greatest slave revolt ever to occur in Virginia.

Further, in order to understand the African in the New World, it is necessary to look honestly at the African. It is even more necessary that we look honestly at the interpretations of the role that the Africans have played in shaping the destiny of this hemisphere.

The fact that slave revolts occurred at all is remarkable. The fact that a large number of these revolts were successful in their early stages is more remarkable. The slaves never accepted their condition passively. In his book American Negro Slave Revolts (the best book on the subject) Dr. Herbert Aptheker records 250 slave revolts.

The protracted fight against the slave system was continued by the escaped slaves and the “free” blacks in the North. The most outstanding of all the escaped slaves was Frederick Douglass.

The career of Frederick Douglas is the greatest dramatic proof of the contributions of the people of African descent to the democratic tradition of this country. From his early life until his death, on February 20, 1895, this great black American was concerned with the universal struggle for freedom of people everywhere. “Under the skin,” he once observed, “we are all the same, and every one of us must join in the fight to further human brotherhood.” The story of his life is mainly the story of a lifelong effort to further human brotherhood. Born a slave, he lifted himself up from bondage by his own efforts, taught himself to read and write, developed great talents as a lecturer, editor, and organizer, became a noted figure in American life, and gained an international reputation as a spokesman for his people. He was an advocate of women’s rights, labor solidarity, and full freedom for all regardless of race, creed, or color. Douglass represents the highest type of progressive leadership emerging from the ranks of the American people.

Of all the books written about Frederick Douglass, the most extensive is the four-volume work by Philip Foner. Still, the best insight into his life comes from him, and in his words. His book, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, is one of the greatest documents of a life in this country’s literature.

Black inventors in general are shamefully neglected in the story of the industrial development of this country. Two new books, Black Pioneers of Science and Invention by Louis Habor (1971) and Black Inventors of America by McKinley Burt, Jr. (1971), have gone a long way toward correcting some of these “sins of omission.” Jan Matzeliger is one of the black inventors whose life is included, in great detail, in these new books.

The play and the motion picture The Great White Hope revived interest in the black prizefighters who came to public attention early in this century. Most of the attention is devoted to Jack Johnson, the subject of the play and the movie. Unfortunately, another good fighter, Peter Jackson, has been forgotten. Jackson fought some of the best fighters of his day without becoming the heavyweight champion. He seemed always on the edge of the big breakthrough, but some of the major white fighters of his time avoided him.

Charles Chesnutt and Paul Laurence Dunbar in their day reached a larger general reading audience than any of the black writers who came before them. Dunbar was the author of four novels, several volumes of poetry, a drama, and a half-dozen collections of short stories. His novel The Sport of the Gods has recently (1971) been reprinted in paperback. This book is considered to be the first protest novel by an Afro-American writer.

Bert Williams, the great comedian, left behind three large notebooks, but was never able to finish a book about his life and the troubled years of his career when he tried to make a name for himself in roles other than as a comedian. There have been many articles written about him, as well as a full-length treatment of his life in the play Star of the Morning by Loften Mitchelle, and Ann Charters’ excellent biography Nobody (1970). He was one of the brightest stars during the golden age of the American theatre. The book Bert Williams, Son of Laughter, written about him in 1923 by Mabel Rowland, is interesting, but it leaves a lot to be desired.

Booker T. Washington stood astride the life of black America in the period between 1895 and 1915. The history of this period is mainly the history of this man and how others reacted to him. His famous “Atlanta Cotton Exposition Address” in 1895 is still being debated. As an educator, as a man, and as an American he was not without greatness. He still has some important things to say to our times. There are many books about him, with varying degrees of good and bad in their interpretations of his life and career. I have found Hugh Hawkins’s Booker T. Washington and His Critics (1962) very useful in providing new insight into this man and his impact on America in general and black America in particular.

William Monroe Trotter is the black radical who for a number of years was lost from history. The writer Lerone Bennett, Jr., figuratively brought him back to life in his book Pioneers in Protest (1968). (See Chapter 15, “The Last Abolitionist.”) The first full-length book about his life. The Guardian of Boston, by Stephen R. Fox, was published in 1971.

W. E. B. Du Bois died in 1963 on the eve of the famous March on Washington. For over fifty years he was the intellectual leader of black America. In the last five years there had been a revival of interest in his life and thought. Nearly all of his books, long out of print, have been republished. A number of new books about him have appeared. Black Titan: W. E. B. Du Bois (1970) an anthology by the editors of Freedomways, is the most extensive collection of articles on Dr. Du Bois that has been published to date.

The following books are also of some interest: W. E. B. Du Bois, Propagandist of the Negro Protest by Elliott M. Rudwick (1968), W. E. B. Du Bois: Negro Leader in a Time of Crisis by Francis L. Broderick (1966), and A. W. E. B. Du Bois Reader, edited by Andrew G. Paschal (1971).

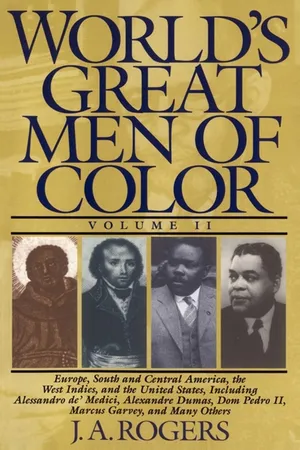

The recent publication (1970) of a paperback edition of Garvey and Garveyism by Mrs. Amy Jacques Garvey, followed by a reprint of Mrs. Garvey’s earlier work The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, proves, if proof is needed, that we are now in the midst of a Marcus Garvey renaissance. In nearly all matters relating to the resurgence of black people, in this country and abroad, there is a reconsideration of this man and his program for the redemption of people of African descent throughout the world. The concept of Black Power that he advocated, using other terms, is now a reality in large areas of the world where people of African origin are predominant. Several books on Marcus Garvey are in preparation. Black Power and the Garvey Movement by Theodore G. Vincent (1971) is the last book on this subject to be published. In this book Mr. Vincent shows that the origins of the black nationalism of Stokely Carmichael, the Republic of New Africa, and the black radicalism of the Black Panther Party can be traced to the Garvey movement.

Hubert Harrison was one of the great minds of the age of black radicalism that saw the emergence of Marcus Garvey, A. Phillip Randolph, Richard B. Moore, and other awakening black thinkers during the early part of this century. He is still not fully rediscovered or appreciated. His many articles have not been brought together in an anthology and his speeches are only partly collected. His life begs for an astute biographer who can see and understand the impact that he had on his time. He was one of the first supporters of Marcus Garvey in this country and he was instrumental in introducing Garvey to his first large audience in Harlem. His book When Africa Awakes, published in 1920, had a profound effect on the Garvey movement and the concept of African redemption.

Ernest E. Just was one of the first American scholars of African origin to make an international impression, during the first two decades of this century. At the age of thirty-one, he was named the first Spingarn Medalist by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. About six months later, in 1916, he obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. After 1924 he became a world figure when leading biologists of Germany considered him the best fitted scientist-biologist to write a treatise on fertilization. His later thesis on the cytoplasm of the cell was so far-ranging that experts said he was twenty-five years ahead of his contemporaries in biological comprehension.

Dr. Charles Drew, an outstanding researcher in blood plasma preservation, described Dr. Just as a “biologist of unusual skill and the greatest of our original thinkers in the field.” He was seen as producing “new concepts of cell life and metabolism which will make him a place for all time.”

Dr. Just wrote two major books and over sixty scientific papers in his field. He was for many years head of the Department of Biological Sciences at Howard University. Like all men of profound learning, Dr. Just was modest. His reputation for integrity, experimental ability, and loyalty was the highest possible. Scientists from all over America and Europe sought him out and studied his work. He also engaged in research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Germany. At times he was a guest at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Naples, and at a similar institution in Sicily. In 1930 he was one of the speakers at the Eleventh International Congress of Zoologists at Padua, Italy. The same year he was elected vice president of the American Society of Zoologists.

Dr. Just was a native of North Carolina. Before his death in 1940, he was a much-honored member of the world’s scientific community.

A short biography of Dr. Ernest Everett Just is included in a recently published book (1970), Black Pioneers of Science and Invention by Louis Haber.

Arthur A. Schomburg, a Puerto Rican of African descent, is responsible for the founding of the world’s most important library on the life, culture, and history of African people the world over. In this century he was one of the pioneer book collectors and a founding member of the Negro Society for Historical Research. His work helped to lay the basis for the Black Studies programs in a large number of present-day institutions. See the article “The Schomburg Collection” by Jean Blackwell Hutson in the book Harlem: A Community in Transition (1969).

For a number of years the black artist in America was ignored. Henry O. Tanner was no exception. This in spite of the fact that his paintings have been bought by galleries all over the world. Some of his most famous paintings are “Christ Walking on Water,” “The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah,” and “The Flight into Egypt.” Henry O. Tanner died in Paris in 1937.

George Washington Carver is the best-known black man of science of our time. His public life and research were based at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. From this base his discoveries became known to the world. In 1939 he was awarded the Theodore Roosevelt Medal for Distinguished Research in Agricultural Chemistry. In 1940 the International Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians gave him a citation for distinguished service. In 1941 the University of Rochester conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Science. Before his death in 1943 he established the George Washington Carver Foundation for Agricultural Research. The following books contain short biographies of George Washington Carver: They Showed the Way by Charlemae Hill Rollins (1964), Black Pioneers of Scien...