- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

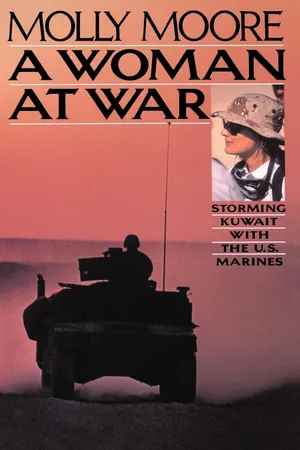

A Woman at War

About this book

A journalist who accompanied a senior commanding general as he led his troops into battle during Desert Storm gives an insider's view of the heroism and tragedy that she witnessed on the front line.

Molly Moore, senior correspondent for The Washington Post, didn’t think she’d be the only US journalist with a close-up view of the Gulf War, but when Lt. Gen. Walter Boomer, commander of the US Marine forces, invited her to shadow him while his troops planned and executed the invasion of Kuwait, that’s exactly the situation she found herself in.

The result of this brave journalistic effort is a vivid and dramatic account of the Gulf War—one that does justice to the diligent, gutsy marines that successfully drove Saddam Hussein’s military from the country, without romanticizing the horrors of battle. Tense, chaotic, and thrumming with emotional resonance, Moore’s examination of the invasion offers indispensable insight into the 100-hour invasion that formed the overture to America’s War on Terror.

Molly Moore, senior correspondent for The Washington Post, didn’t think she’d be the only US journalist with a close-up view of the Gulf War, but when Lt. Gen. Walter Boomer, commander of the US Marine forces, invited her to shadow him while his troops planned and executed the invasion of Kuwait, that’s exactly the situation she found herself in.

The result of this brave journalistic effort is a vivid and dramatic account of the Gulf War—one that does justice to the diligent, gutsy marines that successfully drove Saddam Hussein’s military from the country, without romanticizing the horrors of battle. Tense, chaotic, and thrumming with emotional resonance, Moore’s examination of the invasion offers indispensable insight into the 100-hour invasion that formed the overture to America’s War on Terror.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Woman at War by Molly Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Somewhere in Saudi Arabia

Chapter 1

6:30 p.m., Monday, February 25, 1991, Marine Expeditionary Force Mobile Command Post, Inside Kuwait

The night was so black I could see nothing but the two taillights of the armored war wagon a few yards ahead, piercing the darkness like a pair of sinister red eyes. Each time they seemed on the verge of disappearing, the driver pressed the accelerator, fearful of losing our guide through the dark. The radio next to me crackled with a running catalogue of the dangers that lurked outside.

“Stay close. There’s unexploded ordnance out there. Stay to the right!”

“Be careful on your left. Booby-trapped machine gun!”

We strained to hear the distorted radio voices. I barely breathed, expecting our four-wheel-drive Chevrolet Blazer to explode any minute as we inched along the narrow lanes that had been cleared through the battlefield carpet of unexploded American bombs and Iraqi-laid mines.

“Dismounted infantry on your right!” the radio voice shouted. “We don’t know whether they are good guys or bad guys!”

Another voice cut into the transmission: “More on my left! They have their hands up. About a dozen.”

“Watch out! Watch out!” screamed the first voice. “They have weapons and are in a prone position behind the berms!”

Oh my God, we’re surrounded, I thought, gripping the Kevlar helmet in my lap. I slipped it over my head and tightened the chin strap. I pulled my flak jacket more snugly around my chest.

Our Blazer lurched to a stop. I waited for the gunfire to begin.

The thin metal skin of our vehicle—built for weekend trips to surburban hardware stores, not treks through a war zone—offered little protection. Our Blazer was part of an eleven-vehicle caravan that made up the battlefield command post of Lieutenant General Walter Eugene Boomer, the three-star general directing the Marine Corps’s attack against Iraqi forces. The three Marines in the vehicle with me—a driver, a radioman, and Boomer’s aide-de-camp—were armed with two assault rifles and a 9 millimeter Beretta pistol, hardly a heavy combat force.

No telling what weapons the Iraqi soldiers had out there in the sand dunes. I wondered how they would treat American prisoners of war—especially a thirty-five-year-old female prisoner of war.

I was the senior military correspondent for the The Washington Post, which had sent me to Saudi Arabia two weeks after Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s August 2 invasion of neighboring Kuwait, a country slightly smaller than the state of New Jersey. After five years of covering a peacetime military, this was the second day of my first war. In addition to being the only reporter with Boomer’s command convoy, I was the only woman among thirty-eight men.

A pair of dog tags on a chain around my neck identified me as “Moore, Molly, Catholic, O positive.” Attached to the chain was a “Geneva Conventions Identity Card.” The small print on the back declared that, if taken prisoner, I was “entitled to be given the same treatment and afforded the same privileges as a member of the armed forces.”

That was little consolation. I figured the same treatment as a member of the armed forces probably amounted to slow death by painful torture. The most prominent wording on the card was “United States of America Department of Defense.” What Iraqi soldier, assuming he could even read English, would take time to read the small print identifying me as a civilian?

“They’re coming up out of holes everywhere,” said Sergeant Paul Blair, the radioman in the back seat next to me, repeating the conversation he was monitoring on the radio. In his next breath he asked the driver, “Hey, Sergeant, got any peanut butter up there?”

I couldn’t believe it. Here we were, on the verge of being captured and taken prisoner, and this guy was hungry. I was nauseous.

“Look, there are two lights up to the left,” I whispered hoarsely. They were coming after us. It was only a matter of minutes. I was petrified.

“Radio says it’s our guys going after ten to twelve POWs,” Blair replied nonchalantly.

Prisoners of war? That was a good sign: Maybe they were giving up.

I could hear Blair in the dark next to me, unsnapping the lid to the peanut butter jar he’d bartered from the crew of another vehicle in the convoy earlier in the day.

“It’s so dark out there they could walk right up and look me in the eye and I wouldn’t see them,” muttered Sergeant Mark Chapin from the driver’s seat.

The silences between radio transmissions seemed interminable. For long periods, the only sounds were the four of us shifting in our seats and Blair munching the peanut butter and crackers.

“Be careful, there are friendlies out there,” the radio voice cautioned.

Several Marines from the convoy’s security team were stumbling through the darkness, trying to corral the surrendering Iraqi soldiers while scouting bunkers for armed troops who might not want to give up.

Major Chris Weldon, Boomer’s personal aide, was riding in the front passenger’s seat. He took the radio receiver from Blair and provided running commentary: “POWs are coming out, but they’ve still got troops in the bunkers with weapons…. They’re coming out from all around. They don’t understand English, so that makes it even harder. They’ve still got some back in there that haven’t come up yet.”

“We could be here all night,” I said.

“Uh-huh,” Weldon agreed.

By now, we’d been stopped in the dark for almost an hour. I sat hunched in the backseat, sandwiched between a large bank of radio controls and the butt of Sergeant Blair’s assault rifle, unable to see anything either inside or outside the Blazer. I thought Boomer was insane, running around the desert, picking his way through minefields filled with Iraqi soldiers poised to capture the highest-ranking U.S. military commander on the Kuwait battlefield.

The previous day, after thirty-eight days of intensive aerial bombing had failed to dislodge Saddam’s forces from Kuwait, about 40,000 Marines had charged through the minefields and obstacle belts into the jaws of the Iraqi defenses. To the west, about 260,000 U.S. Army, British, and French troops were sweeping across the Iraqi desert in a vast arc that was now beginning to converge into an armored fist designed to slam into the Iraqi Republican Guard.

Thousands of American military vehicles—tanks, assault vehicles, fuel trucks—had driven through this same lane in the last thirty-six hours. I couldn’t believe the Marines were only now discovering Iraqi troops still hiding in the trenches and bunkers.

The first day and a half of the ground war had gone far better than expected for the American forces. Front-line Iraqi troops were surrendering by the thousands. Still, American commanders believed the toughest battles lay ahead. Saddam had not yet unleashed his chemical weapons, his strongest forces in Kuwait remained entrenched to our north, and the Army had barely begun its attack on the elite Republican Guard forces to our west.

As we set in the dark, the Marines’ rear command post, about thirty miles behind us in Saudi Arabia, radioed for Boomer. Weldon dispatched our driver to inch his way through the darkness to the command vehicle, warning, “Stay on the road!”

Meanwhile, Weldon held the radio receiver with one hand as he fumbled through his pockets with the other. “You got a notebook and pen?” he whispered at me. “Take this down.”

Taking notes was impossible; the security teams had ordered all lights doused as soon as the Iraqi soldiers were spotted. Unable to write, I’d flipped on my tape recorder an hour earlier to capture the radio dialogue.

Now Weldon handed me his red flashlight. “Write down what you hear me repeat,” he ordered.

I’d been demoted to a major’s scribe. Since there was no way for me to do my own job, I saw no harm in making this small contribution to the war cause.

“1st Division consolidating along Phase Line Red,” Weldon said, echoing the voice on the radio. Phase Line Red was about sixteen miles inside Kuwait, where Boomer wanted both of his divisions to consolidate for the night.

I scratched the words across the page. The letters disappeared as soon as I wrote them. I couldn’t figure out what was wrong. Suddenly, I realized I was writing with a red pen, the color rendered invisible by the red-tinted flashlight. My role as a war scribe was very short-lived.

A few minutes later the door opened and Boomer slipped into the driver’s seat. “You have a new driver. Where do you want to go? Kuwait City?” It was Boomer’s first attempt at humor since I’d linked up with him at his command post three days earlier. Sitting inside an armored command vehicle in the middle of a dark minefield with Iraqis popping out of holes seemed to have improved his disposition.

Boomer didn’t fit the movie image of a brash, swashbuckling general. He spoke in a soft Virginia Tidewater drawl and at age fifty-two still retained a hint of his country-boy shyness. His helmet hid two of his most conspicuous features, oversized ears. A pale complexion, thin face, high cheekbones, and slender frame made him look almost too delicate to have survived two grisly combat tours in Vietnam. Even so, he had one characteristic perfected by many general officers: a cold, steely gaze that seemed to bore through the flesh of anyone who angered or disappointed him.

“How are you doing?” Boomer asked, glancing back at me from the front seat.

“Well, you’re certainly not a dull date,” I replied.

Weldon was working the radios. “Sir, unconfirmed report of mustard gas delivered on 1st Division.”

“Oh, that’s bullshit,” Boomer snapped. “There’s no gas. They checked it out.”

“Okay, good,” Weldon murmured.

I had met Boomer in my first weeks on the Pentagon beat more than five years earlier, just after he’d been promoted to a one-star general and was named chief of public affairs for the Marine Corps. I’d interviewed him regularly during the six-month buildup of American forces in Saudi Arabia. In late February, five weeks after the air war had begun, Boomer invited six reporters to his forward command post to observe the start of the ground war. I was the only one who accepted the invitation.

We’d been on the battlefield since early morning, when Boomer, worried that he could not properly command the fast-moving forces from his fortified headquarters inside Saudi Arabia—and being somewhat of a kamikaze general—took his top commanders on the road to direct his troops from the front of the battlefield. He invited me to come along. Some of his senior aides objected strongly to both decisions. It was unclear whether they considered it more dangerous for Boomer to be roaming around the battlefield or to have a reporter watching his every move.

Sergeant Chapin leaned through the open door. “How are you doing, sir?”

“Fine. Can’t dance.” Boomer’s voice dissolved into a raspy cough.

He tried to explain the snippets we’d been hearing over the radio. “Some of ’em were out with their hands up. Some were hiding behind berms with weapons. Problem is, it’s so dark.”

“1st Division is consolidating along Phase Line Red,” Weldon interrupted. He turned back to the radio receiver. “Is there anything else to pass? Over.”

“I want to talk to him,” Boomer told Weldon, who was now on the radio to Major General Richard D. Hearney, a stern-faced aviator running the rear command post in Saudi Arabia in Boomer’s absence.

Several critical communications links, including a satellite antenna that was supposed to allow Boomer to communicate with his deputy in the rear as well as General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, the senior U.S. commander, in Riyadh, were in our Blazer. In the twelve hours we’d been rumbling across the battlefield, Boomer’s mobile communications network had failed repeatedly, leaving him incommunicado with some of his senior war-fighting commanders.

“One MEF, this is One MEF Forward, stand by for CG,” Weldon said into the radio. The cryptic shorthand signaled the I Marine Expeditionary Force headquarters in Saudi Arabia that Boomer, the commanding general, was trying to reach his staff from his battlefield command post, which was designated I MEF Forward.

Boomer took the receiver. “One MEF, one MEF, CG. Over.”

No response.

He tried again, “One MEF, One MEF, CG One MEF. Over.” A short pause. “Roger, is the deputy CG around? Over.”

Hearney replied, asking Boomer how the mobile command post was faring.

“We’re doing okay,” Boomer said between coughs. “EPWs are complicating everybody’s life, including ours this evening,” he added, referring to enemy prisoners. “We’re moving up to join 2nd Marine Division, but it’s really black out here with smoke, so we’re a little bit separated. But everybody’s okay. Over.”

He suddenly sounded extremely tired.

“In case I don’t have a chance to set up the CentCom component nets, call in and tell ’em everything’s okay…. The day has gone extremely well from my perspective. Lot of little fights all around. You’d knock out a couple of tanks and they’d give up. Break. Christ, there’s EPWs everywhere, including up in front of our column here in the pitch dark. Over.”

Hearney agreed to contact the U.S. Central Command headquarters in Riyadh, where General Schwarzkopf was directing the war from Saudi Arabia’s equivalent of the Pentagon.

“Okay, I have nothing further,” Boomer continued. “If we get settled down here and get some other radios set up, I’ll check back in with you later on. Over. Reiterate, I’m really pleased with the way the day went. As far as I know, we had no KIAs today.” I found it amazing, and improbable, that no Marine had been killed during the second day of combat.

Hearney said his reports indicated some Marine units had engaged in fierce combat during the day and several Marines had been wounded.

“Roger, it was hard to monitor,” Boomer responded. “But overall we did extremely well…. I have nothing further. One MEF out.”

“I’m gonna go on back up,” Boomer said, sliding out of the Blazer.

“You going to make room for some of those EPWs in your vehicle?” I suggested.

“Hell, no.” He poked his head back inside, surveying our cramped space. “You don’t have any room for ’em here either. See you in a little while.”

Our driver, Chapin, climbed back inside the truck and the four of us continued monitoring the radio chatter.

“You’re one of the select few of thirty-eight people watching history being made,” Weldon proffered as Boomer disappeared into the night. “We’re running the war from two LAVs and a Blazer.”

Boomer’s LAV—or light armored vehicle—was stuffed with radios that were supposed to allow him to talk with air and ground commanders across the battlefield. But the war was moving so fast and the battlefield was so chaotic that most of Boomer’s commanders had outrun the ranges of his radios. It was a stark contrast to the surgical image of combat that had been created by the U.S. Central Command and the Pentagon during the thirty-eight days of the allied air campaign, with its parade of videos depicting high-technology, precision-perfect bombing runs and missile hits.

“Ive got to make a head call,” Sergeant Chapin announced after an unusually long silence from the radios.

“Don’t go far,” Weldon warned.

Chapin stepped out and felt his way to the back of the Blazer. Suddenly we heard a loud yelp. A minute later he returned, badly shaken. The driver from the military jeep behind us had the same urge. The two men had bumped into each other in the dark. “I was so scared I nearly shot him,” Chapin said, trying to shake the jitters.

About 10:30 p.m., with all the Iraqi soldiers flushed from their bunkers and under guard, the convoy inched forward once again. Within minutes it stopped. The pattern was repeated, start and stop, start and stop. Movement was hazardous in darkness made even more impenetrable by the smoky clouds of burning oil wells.

“I can’t see anything,” Chapin complained, head craned over the steering wheel. Suddenly his head nodded. “Oh, God. I’m going to be sick. I’ve got to get out.” He opened the door and vomited into the sand.

“Are you all right? Can your drive?” Weldon shouted, reaching over to grab the steering wheel.

The only response was more gagging and another round of vomit. I scrambled to find the roll of toilet paper I’d seen on the floor in the back and passed it up to Weldon.

“I’ll be fine, sir,” Chapin said gamely.

He pushed open the door again and stuck his head out. The red taillights in front of us were becoming smaller and smaller.

“Blair!” barked Weldon. “Take his place!”

Sergeant Blair squeezed out of the seat next to me and made room for the driver to climb in the back. I had visions of poor Chapin puking all over my lap.

“Uh, maybe he should sit up front so he can get out if he has to,” I suggested.

“I think that’s a good idea, ma’am,” he said, his voice hesitating.

I felt so sorry for him. Conditions were miserable enough without being sick and having the added embarrassment of throwing up in front of your colleagues and a female reporter.

Over the next fifteen minutes, Chapin seemed to regain his compsure and began apologizing profusely. “It must have been those two MREs I had for lunch,” he said sheepishly.

“Anybody who eats two MREs in one sitting is asking for trouble,” I kidded Chapin.

When I’d first arrived in Saudi Arabia, an Army private asked me if I knew what MRE meant. “Sure,” I replied. “Meals-Ready-to-Eat.”

“No, ma’am,” countered the private. “Meals Rejected by Ethiopians.”

Whatever they were called, I—along with thousands of troops in Saudi Arabia—detested the modern-day military replacement for C rations. The meals, packaged in unappetizing dirt-brown plastic pouches, came in a variety of menus, ranging from freeze-dried pork patties with the consistency of Styrofoam to packets of chicken à la king with the smell and appearance of expensive cat food. I usually ate little more than the crackers with squeeza...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Glossary

- Acknowledgments

- A Note to the Reader

- Part I Somewhere in Saudi Arabia

- Part II Boomer’s War

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index

- Photo Section