- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alcohol and the Addictive Brain

About this book

An understanding of the nature and progression of alcohol addiction has emerged: alcoholism as the result of an imbalance in the brain's natural production of neurotransmitters critical to our sense of wellbeing. This imbalance, which an increasing amount of evidence is demonstrating to be genetically influenced, produces a craving temporarily satisfied by drinking. Alcohol and the Addictive Brain is an account of the scientific discoveries concerning alcoholism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Alcohol and the Addictive Brain by Kenneth Blum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Addiction in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION TWO

THE SEARCH FOR THE SOLUTION

5

The Neuron: A Primer of Brain Function

In order to follow the story of research on the causes of addiction, readers will need to know some basic facts of brain neurochemistry. In this chapter, I will describe the key structures in brain neurons, and chemical reactions between them that generate feelings of well-being and satisfaction, or frustration, anxiety, anger, or depression.

The chapter may be difficult reading for many, but it will be well worth the time and effort. It provides a foundation for understanding the work of the scientists described in subsequent chapters.

IN THE NEURON

The brain is composed largely of linked nerve cells or neurons. They perform two broad functions: they send messages to other neurons, and receive messages from other neurons. This interaction determines our mental and emotional functioning.

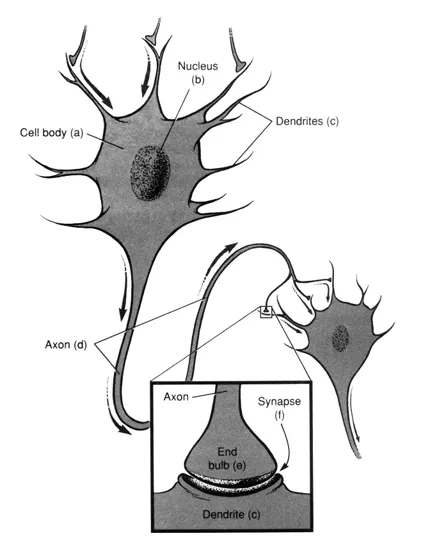

- The cell body (a, Fig. 5-1) is a chemical factory where messenger and control substances are manufactured.

- The nucleus (b) contains the chromosomes which, in turn, contain the genes that are made up of long chains of nucleotides. The nucleotides make up deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). The DNA lays down the code for ribonucleic acid (RNA), and RNA, in turn, controls the synthesis of proteins which form neurotransmitters and enzymes.

- The tiny, treelike elements on one end of the neuron are called dendrites (c). They are the receivers that accept messages from other neurons. A given neuron may have hundreds or even thousands of dendrites linking it to other neurons. Since there are some 50 billion neurons, the total number of possible interactions is too great for comprehension.

Figure 5-1 The Structure of the Neuron. Structural representation of the neuron. Close-up in box illustrates the anatomy of the synapse.

Figure 5-1 The Structure of the Neuron. Structural representation of the neuron. Close-up in box illustrates the anatomy of the synapse. - A single large element extending outward from the other end of the cell body is called the axon (d). It carries messages to dendrites of adjacent neurons. Together, the axon and the dendrites act as “wired connectors” linking the neurons.

- Located at the end of the axon is a spherical protuberance called the end bulb (e). Or the axon may proliferate into multiple end bulbs. The outer surface of an end bulb constitutes one wall of the synapse (f) which acts as a chemical switch to control communication between the neurons.

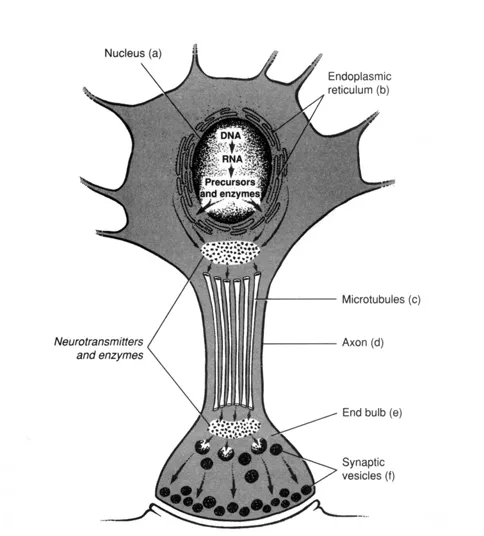

- In the nucleus of the neuron (a, Fig. 5-2), the DNA molecules provide the blueprint which controls ribonucleic acid (RNA) manufacture.

- RNA, in turn, transmits instructions to the “factory” to control the design and production of neuronal proteins which act as building blocks for the neurotransmitters that carry messages between neurons, and for enzymes that regulate the synthesis and breakdown of neurotransmitters.

DNA and RNA are produced inside the nucleus. Proteins are produced in the cell body outside the nucleus in the endoplasmic reticulum (b). The work of the endoplasmic reticulum is to produce certain neurotransmitters and enzymes.

Some neurons produce excitatory neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine; some produce inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA); and some produce both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, enabling a neuron to transmit more than one type of message. But a particular neurotransmitter in a particular neuron can transmit only one specific message: stimulate or inhibit. All neurotransmitter molecules of a given type—for example, norepinephrine—are structurally identical.

Neurotransmitters and certain enzymes are carried from the cell body through microtubules (c); along the axon (d); into the end bulb (e); and into small, spherical sacs called synaptic vesicles (f ) whose position along the membrane is controlled by the genes. These vesicles are only 400 to 1200 angstroms in diameter. (An angstrom is one ten billionth of a meter. )

All of the molecules in a given vesicle are identical; that is, a vesicle will contain only norepinephrine molecules or only GABA molecules. If a particular neuron manufactures both norepinephrine and GABA, some of the vesicles will be filled with norepinephrine molecules, and some with GABA molecules.

Within the end bulb, enzymes which have migrated from the cell body act to regulate the supply of neurotransmitters by controlling their metabolism, or breakdown. This action prevents an oversupply of neurotransmitters that would result in overstimulation or overinhibition of the dendrite of the next neuron in the sequence. For example, monoamine oxidase prevents an oversupply of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine by converting it into a nonactive compound.

Figure 5-2 Nucleus and End Bulb. Expanded representation of the nucleus and end bulb. Arrows show the flow of neurotransmitters out of the endoplasmic reticulum (b) through the microtubules (c) to the end bulb (e).

AT THE SYNAPSE

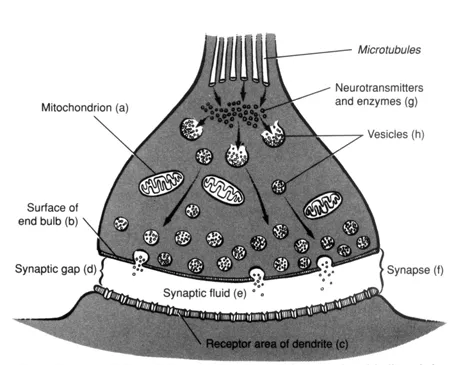

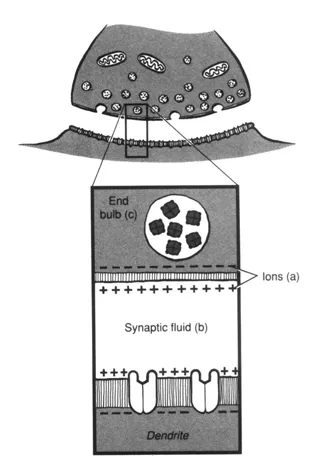

Also within the end bulb, substructures called mitochondrions (a, Fig. 5-3) convert sugar and oxygen into energy-releasing molecules for use by the neuron as needed. Across from the surface of the end bulb (b) is the receptor area of the dendrite of an adjacent neuron (c). The two surfaces are separated by the synaptic gap (d), 50 to 200 angstroms in width. This space is filled with a synaptic fluid (e), similar to salty water. It acts as an electrolyte to promote electrical activity at the interface.

The two surfaces and the intervening fluid constitute a synapse (f). The synaptic fluid contains positively charged ions such as sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium; and negatively charged ions such as chloride and phosphate.

Figure 5-3 End Bulb and Synapse. Close-up of the axonal end bulb and the synapse. Arrows show flow of neurotransmitter release.

NEURONAL TRANSMISSION

Transmission of neurotransmitters across the synapse involves the following actions:

- Neurotransmitters (g)—and sometimes enzymes—migrate into the vesicles (h).

- In the resting phase, the ions (a) in the synaptic fluid (b, Fig. 5-4) are in electrical balance but the area is positive relative to the end bulb. Inside the bulb (c) there is a deficiency of positively charged ions, creating a net negative charge. The reason is that in the resting phase the neuronal membrane does not permit the entry of positively charged ions.

Figure 5-4 Resting Phase of the Neuron. Close-up of the resting phase, illustrating the axon-dendrite resting change.

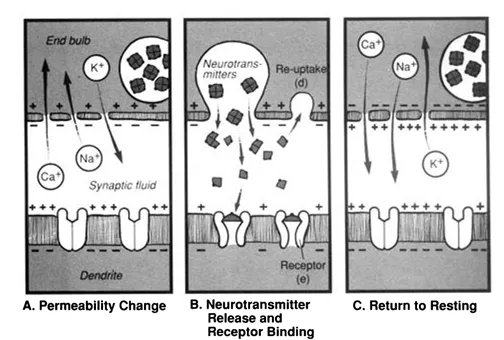

Figure 5-4 Resting Phase of the Neuron. Close-up of the resting phase, illustrating the axon-dendrite resting change. - In the action phase, the neuronal membrane changes its permeability (A, Fig. 5-5) to permit positively charged sodium (Na) and calcium (Ca) ions from the synaptic fluid to enter the end bulb. Simultaneously, potassium (K) is pumped out to maintain a balance and prevent an excessive positive charge.

- During this brief action phase, external calcium ions penetrate the membrane that encloses the end bulb. This action involves several other enzymes and proteins, and causes a fusion of the walls of the vesicles with the membrane. When this occurs, packets of neurotransmitter molecules are released (B) through the end bulb membrane into the synaptic fluid.

- Some of these molecules are immediately returned to the neuron by a pumping action involving sodium and potassium ions (d): the “re-uptake mechanism.”

Figure 5-5 Action Phase of the Neuron. In the action phase, ions and neurotransmitters flow from synaptic fluid to end bulb and from axon to dendrite, and return to rest. Arrows indicate direction of flow.

Figure 5-5 Action Phase of the Neuron. In the action phase, ions and neurotransmitters flow from synaptic fluid to end bulb and from axon to dendrite, and return to rest. Arrows indicate direction of flow. - Some molecules are metabolized or destroyed by enzymes in the synaptic fluid.

- The remainder move across the synaptic gap and come into contact with specialized molecules called receptors (e) in the membrane of a dendrite of the second neuron.

At the height of this action phase, the interior of the cell has a strong positive charge relative to the synaptic fluid. This positive state lasts only 1/10,000 of a second, followed by a pumping out of positive sodium and calcium ions to bring the cell to a negative state again: the resting state (C).

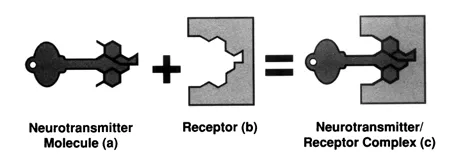

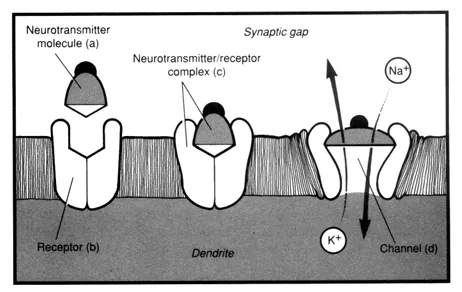

- When one of the neurotransmitter molecules (a, Fig. 5-6) comes into contact with a receptor cell (b) that has the right shape and electrical charge, it fits it “like a key in a lock” and binds to the receptor to form a neurotransmitter-receptor complex (c).

If we take a closer look, when an excitatory neurotransmitter molecule (a, Fig. 5-7) approaches the receptor (b) and forms a neurotransmitter-receptor complex (c), it opens a channel for the exit of potassium ions, and the entry of sodium and calcium ions into the second neuron (d), activating it and initiating a new neuronal sequence.

- After activating the receptor, the neurotransmitter molecule is dissociated from the receptor, and is either metabolized by an enzyme in the synapse, or is returned to the end bulb of the first neuron to reenter a vesicle or be metabolized by internal enzymes.

Figure 5-6 Neurotransmitter-Receptor Complex. Schematic of the structure of the neurotransmitter-receptor complex. The “lock and key” concept is shown.

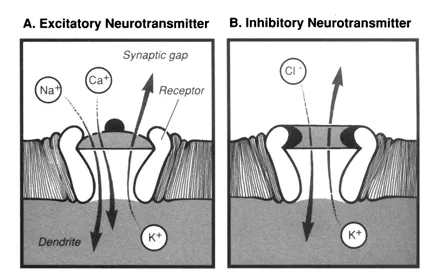

Figure 5-6 Neurotransmitter-Receptor Complex. Schematic of the structure of the neurotransmitter-receptor complex. The “lock and key” concept is shown. - The effect of an excitatory neurotransmitter on a receptor (A, Fig. 5-8) is to permit positively charged sodium and calcium to enter, and potassium to exit the dendrite. These actions excite the second neuron in a controlled manner. The action requires approximately 2/10,000 of a second. An example would be the excitatory action of norepinephrine; for example, increasing neuronal firing.

- The effect of an inhibitory neurotransmitter on a receptor (B) is to permit negatively charged chloride ions to enter the dendrite, and potassium to exit. These actions inhibit cell activity. An example would be the inhibitory action of GABA, reducing neuronal firing.

If an excitatory neurotransmitter is involved, three “second-messenger” systems affect the function of the adjacent neuron:

- A compound called adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP) is activated. This initiation of the second messenger response sequence prepares the way for the eventual release of neurotransmitters from the vesicles in the axon.

- The Protein Phosphorylation System (PPS) provides energy for the eventual release of neurotransmitters from vesicles in the end bulb.

Figure 5-7 Excitatory Action at the Synapse. Action of an excitatory neurotransmitter molecule in the synaptic gap.

Figure 5-7 Excitatory Action at the Synapse. Action of an excitatory neurotransmitter molecule in the synaptic gap. - Intraneuronal calcium enables the fusion of the vesicles with the membrane of the end bulb, opening the way for movement of a neurotransmitter across the synapse to an adjacent neuron.

This completes one full cycle of neuronal activity, the fundamental sequence of stimulus and response that determines behavior.

NEUROTRANSMITTERS

Essential to understanding the function of the neuron is an understanding of the nature and function of neurotransmitters. These substances are manufactured in the neuron, and can be divided into two types, both of which are made from amino acids, the basic building blocks of protein. The first type is the monoamines. They are composed entirely of single amino acids derived from food and carried by the blood into the brain. The second type is the neuropeptides. They are made from giant, linked amino acids called peptides produced in the endoplasmic reticulum. In the giant form they are inactive; that is, they have no biological activity, but are broken down into smaller, active neuropeptides.

Figure 5-8 Comparison of Excitatory Neurotransmitter Action and Inhibitory Neurotransmitter Action at the Synapse

Monoamines

The key monoamines are:

1. Serotonin. Serotonin is made from the amino acid tryptophan through the action of two enzymes: tryptophan hydroxylase and amino acid decarboxylase. It is metabolized or broken down in the brain by two other enzymes: monoamine oxidase, and aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Serotonin messages promote feelings of well-being and sleep, tend to reduce aggression and compulsive behaviors such as drug abuse and excessive drinking or eating, elevate the pain threshold, and aid in the regulation of the cardiovascular system.

2. Dopamine. Dopamine is made from the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine through the action of three enzymes: phenylalanine hydroxylase, tyrosine hydroxylase, and amino acid decarboxylase. It is metabolized by the enzymes monoamine oxidase, catechol-O-methyl transferase, aldehyde reductase, and alcohol dehydrogenase.

Dopamine messages increase feelings of well-being, tend to increase aggression, increase alertness and sexual excitement, and reduce compulsive behavior. In some individuals, however, an excess of dopamine may cause psychotic behavior.

3. Norepinephrine. Norepinephrine is made from dopamine, through the action of a single enzyme: dopamine beta-hydroxylase. It is metabolized by the enzymes monoamine oxidase, catechol-O-methyl transferase, aldehyde reductase, and alcohol dehydrogenase.

Norepinephrine messages increase feelings of well-being, and reduce compulsive behavior. An excess may induce anxiety, increase heart rate and blood pressure, and cause tremors in patients undergoing withdrawal from alcohol and drug addiction.

4. GABA. GABA is made from the amino acid glutamic acid, which in turn is derived either from another amino acid called glutamine, or from the sugar glucose. The activating enzyme in the synthesis is glutamic acid decarboxylase. It is metabolized by the enzymes GABA transaminase and succinic semi-aldehyde dehydrogenase.

GABA messages reduce anxiety and compulsive beha...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Section One: The Problem And Early Attempts To Define And Cope With It

- Section Two: The Search For The Solution

- Notes

- Glossary

- Index