- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

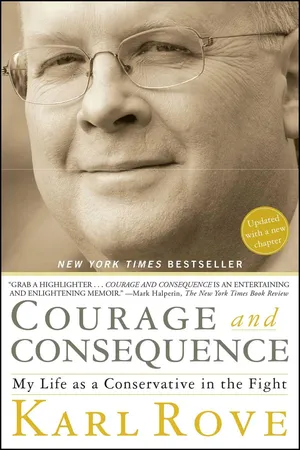

From the moment he set foot on it, Karl Rove has rocked America’s political stage. He ran the national College Republicans at twenty-two, and turned a Texas dominated by Democrats into a bastion for Republicans. He launched George W. Bush to national renown by unseating a popular Democratic governor, and then orchestrated a GOP White House win at a time when voters had little reason to throw out the incumbent party. For engineering victory after unlikely victory, Rove became known as “the Architect.”

Because of his success, Rove has been attacked his entire career, accused of everything from campaign chicanery to ideological divisiveness. In this frank memoir, Rove responds to critics, passionately articulates his political philosophy, and defends the choices he made on the campaign trail and in the White House. He addresses controversies head-on— from his role in the contest between Bush and Senator John McCain in South Carolina to the charges that Bush misled the nation on Iraq. In the course of putting the record straight, Rove takes on Democratic leaders who acted cynically or deviously behind closed doors, and even Republicans who lacked backbone at crucial moments.

Courage and Consequence is also the first intimate account from the highest level at the White House of one of the most headline-making presidencies of the modern age. Rove takes readers behind the scenes of the bitterly contested 2000 presidential contest, of tense moments aboard Air Force One on 9/11, of the decision to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, of the hard-won 2004 reelection fight, and even of his painful three years fending off an indictment by Special Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald. In the process, he spells out what it takes to win elections and how to govern successfully once a candidate has won.

Rove is candid about his mistakes in the West Wing and in his campaigns, and talks frankly about the heartbreak of his early family years. But Courage and Consequence is ultimately about the joy of a life committed to the conservative cause, a life spent in political combat and service to country, no matter the costs.

Because of his success, Rove has been attacked his entire career, accused of everything from campaign chicanery to ideological divisiveness. In this frank memoir, Rove responds to critics, passionately articulates his political philosophy, and defends the choices he made on the campaign trail and in the White House. He addresses controversies head-on— from his role in the contest between Bush and Senator John McCain in South Carolina to the charges that Bush misled the nation on Iraq. In the course of putting the record straight, Rove takes on Democratic leaders who acted cynically or deviously behind closed doors, and even Republicans who lacked backbone at crucial moments.

Courage and Consequence is also the first intimate account from the highest level at the White House of one of the most headline-making presidencies of the modern age. Rove takes readers behind the scenes of the bitterly contested 2000 presidential contest, of tense moments aboard Air Force One on 9/11, of the decision to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, of the hard-won 2004 reelection fight, and even of his painful three years fending off an indictment by Special Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald. In the process, he spells out what it takes to win elections and how to govern successfully once a candidate has won.

Rove is candid about his mistakes in the West Wing and in his campaigns, and talks frankly about the heartbreak of his early family years. But Courage and Consequence is ultimately about the joy of a life committed to the conservative cause, a life spent in political combat and service to country, no matter the costs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Courage and Consequence by Karl Rove in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Broken Family on the Western Front

Have you heard the joke about the Norwegian farmer who loved his wife so much he almost told her? My father—Louis C. Rove, Jr.—was a Norwegian, one of those taciturn midwesterners who held back a lot. But in the last decades of life, Dad began to open up about himself, his marriage, and my childhood. He would meet me and my wife, Darby, in Santa Fe for the opera and the Chamber Music Festival each summer, and while exploring New Mexico, he would reveal secrets of our family life that were shocking because they were so intimate. But I disclose them here because my early years have been painted very differently. There is something to be said about setting the record straight, especially when it involves your kin.

So before I get to my career in politics, I want to tell the real story of my family, with all the love and heartbreak it contained. My father was a geologist. At about six feet tall, trim, with short-cropped blond hair and glasses, he had a kind but somber demeanor. Born in Wisconsin, he served briefly in the Navy at the end of World War II. Afterward, he spent a year at Hope College in Michigan. Inspired by his uncle Olaf Rove, a consulting geologist of some renown, my father then transferred to the Colorado School of Mines, in Golden, Colorado.

It was there that he met my mother, Reba Wood. There were many differences. Dad was college-educated, well-read, and had grown up in a sensibly middle-class home with books, classical music, and opera. My mother never went to college, never had been exposed to books or classical music, and wasn’t interested in them. It may have been that she was the only girl in a family that prized boys, or else it was an early misfortune that was hidden from me, but regardless, while she appeared strong and in control, in reality she was fragile. Her brittleness, emotional pain, and suffering were out of most people’s view. But she and Dad were drawn to each other: he to her beauty and passion, and she to his solid dependability and dashing good looks. For a very long time, they were very much in love.

Mom was the only daughter of Robert G. and Elsie Wood and had three younger brothers. My maternal grandfather never went to college, but he was full of drive, dreams, and integrity. During the Depression, he found work on a Colorado Highway Department crew. Later, from a wooden shelf on the backseat of his car, Grandpa started selling butcher knives he had bought on consignment, to out-of-the-way grocery stores in southern Colorado. He eventually built it into a business—Robert G. Wood & Company, “Quality Butcher Supplies.” It was to provide a good livelihood for three generations of Woods. I was to spend many happy hours in his shop in Denver and around Grandfather Wood and my three uncles.

My grandparents lived in the same house for most of their adult lives, at 3045 Lowell Boulevard in Denver. The only luxury they allowed themselves was travel, recorded on a primitive motion picture camera by my grandfather. Over a twenty-year period, they went to Mexico, worked their way through South America; flew to Hawaii; traveled to Lebanon, Israel, and Egypt in simpler times in the region; visited Cambodia and Vietnam before they became dangerous; and went to Japan when it no longer was. It was a highlight after each trip to go to our grandparents’ house to see my grandfather’s movies, carefully narrated by him. My grandmother decorated their house with things brought home from their travels, whether trinkets, rubbings from the Angkor Wat temples, or Peruvian village retablos.

When my grandfather died of a heart attack on Labor Day 1974, my grandmother attempted suicide by shooting herself in the stomach. She lived another twenty-five years in pain and loneliness, mourning her husband and, I later was to discover, indirectly showing her loved ones that suicide was an acceptable way to deal with hardship.

I was born early on Christmas Day 1950, in a hospital elevator in Denver, Colorado. I guess I started out eager to get going. I grew up on the genteel fringes of the lower middle class, the second oldest in what became a family of five kids—three boys (an older brother and a younger one) and two sisters (both younger). We lived in Colorado until I was nine; in Sparks, Nevada, until I was fifteen; and then in Holladay, Utah, as my father followed opportunities in the mining business.

In the 1950s, being a young geologist specializing in uranium, lead, zinc, and copper was not a lucrative calling, but it was a demanding profession. Dad was often gone for months at a time on stints in Angola and Mozambique; in Aruba; in Manitoba, Alberta, and on the Queen Charlotte Islands of Canada; in Alaska; and all across the western part of the lower forty-eight states. His trips prompted a childish interest in vexillology: I used to draw pictures of the flags of the countries and states he worked in and treasured a small book of flags of nations and history he gave me.

I keep a picture of my father on a shelf near my desk. It was taken in a remote corner of Angola in the early 1950s. He is surrounded by bush children who probably had not seen many Westerners. When I was young, the picture seemed to me to be of a young, tanned demigod. In reality, he was a gangly young man fresh out of college, trying to chart his way in life.

We were brought up on tales of Africa, of his beloved monkey Chico, who later died in the Lisbon Zoo, and how my father had come to possess an eighteen-foot-long snakeskin, a zebra hide, and a rhinoceros horn—revered as sacred family totems in our home. We showed them to our friends with great ceremony.

In Colorado, our family first lived briefly in the company town of Kokomo, near the Climax mine north of Leadville. Then we moved to a house in a big field outside Arvada. There was a large pond in the southeast corner and a ditch meandered over the lower part of the property, providing welcome territory for games and exploring.

We had a chicken coop and a garden that provided us with much-needed eggs, carrots, tomatoes, and green beans. To this day, I think there’s almost nothing better than a ripe strawberry plucked fresh from the garden and nothing worse than eggplant, especially when it’s been fried the night before and served cold for breakfast because you left it on your dinner plate.

We never lacked for anything we really needed, but the family budget was always under pressure. My mother could spend more money to less effect than almost anyone I have ever known. To her credit, she tried earning money, but her ideas usually lasted only a season or two. One year, we collected pinecones and sold them to local nurseries. Then Mom became an Avon lady and my brother and I (and eventually all the kids) became experts at bagging orders. I knew by heart the code for almost every shade of Avon lipstick. We delivered newspapers, cut grass, babysat the neighbors’ kids, sold lemonade, and helped out at Grandfather’s store. As a teenager, I waited tables and washed dishes, ran a cash register at a hippie shop that sold patchouli oil, worked in a hospital kitchen, and held down the night shift at a convenience store. My parents made me quit the last job after I was robbed twice—once with a pistol and the second time with a sawed-off shotgun. I was stoic during the robberies, but shaken afterward and happy my parents insisted I quit.

Even with all these efforts, and especially when we were young, there didn’t seem to be enough money. The Christmas I turned five, the bonus Dad had been promised turned out to be a pittance, leaving him with no money for presents, so he talked a buddy who flew a helicopter like the one in the M*A*S*H television show into landing his chopper in the dusty field surrounding our house and taking us up. Dad explained it was Santa’s helicopter, so we had to take our ride the day before Christmas rather than on Christmas itself. It’s still the best Christmas I ever had.

For my brothers and sisters and me, it seemed like an idyllic childhood, with Boy Scouts, Little League, playing “war” in the fields nearby, stamp and coin collections, trading baseball cards, and fried chicken dinners on Sunday at our grandparents’ house, where we watched Bonanza and The Wonderful World of Disney on their color TV. I looked up to my older brother, Eric, even though he used to beat me up, as all older brothers do. I thought he was the smartest person I knew. He spent his life outdoors, working in highway construction after attending the University of Nevada. Alma, six years younger than me, looked the most like Mom and, like her, had more than her share of misfortune in life. Olaf, eight years younger than me, was a happy and thoroughly content child who grew up to run computer systems. And the baby, Reba—nine years younger than me—was especially smart, disciplined, funny, prone to tricks, and, at least when it comes to her childhood memories, also prone to good-hearted exaggeration. We were an outgoing, active group.

We didn’t have a television at home until we moved to Nevada. Dad said it was because he wanted us to read, exercise our minds, and do our homework. I suspect family finances had something to do with it, too. When he was home and read to us or made us listen to the opera sponsored by Texaco and explained the stories we were hearing, not having a television didn’t matter so much.

During breaks from school, Dad would take his children with him when he had geological fieldwork nearby. It fostered a love of the open spaces of the West and of nature and its processes. Dad’s frequent travels and our family’s mobility made me a natural extrovert, with both the ability and the need to make friends and connect with others. And living in a tidy middle-class household with only a few, but nice, pieces of furniture and art never made me yearn for material things.

Mom ran the household in Dad’s absence and she could alternately act like a Marine drill instructor or a soft, caring figure. She was not stable or predictable and had a penchant for melodrama. The family was always headed over a cliff tomorrow. She would be seized by some crisis and then share her fear with her children. The moment would eventually pass for her, but some anxiety and uncertainty would remain with us.

My father and my grandfather helped organize the First Presbyterian Church of Golden, Colorado, so there was also Sunday school and summer church camp. The young minister they called to the pulpit told me many years later that he and my dad attended a local Presbyterian meeting where the little daughter of one of the pastors played the piano to entertain the group. She was Condoleezza Rice, whose father, John, was an associate pastor at Montview Presbyterian Church in Denver. My parents were later active in helping form Westminster Presbyterian Church in Sparks, pressing me into service as a canvasser and then an usher.

We caught glimpses of life’s casual cruelty, especially after we moved to Nevada when I was nine. Sometimes neighborhood kids would show up unannounced for dinner at our house, which was inevitably spaghetti or macaroni and cheese with hamburger meat. I learned that these kids were from families where the parents had gambled away their paychecks. The experience gave me a lifelong aversion to gambling.

Because my father was often gone and my mother prone to erratic behavior, I took refuge in books. They were dependable, solid, and an exciting escape to a better place. “There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away,” Emily Dickinson once wrote. I wasn’t good at sports, and my family couldn’t afford entertainment, so books were my savior: you can blame them for my love of politics, and the career it produced.

I still have the first frigate I can remember reading: a gift from my second-grade teacher called Great Moments in History. Its pages on the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Alamo, and the Civil War fascinated me. I read everything I could get my hands on, especially biographies and histories. The coming of the centennial of the Civil War in 1960 meant I was exposed at the age of seven to a flood of books on it.

To me, the Civil War was not just compelling and stirring, it was real. It was a true drama of real people with real lives whose decisions settled the question of whether the young democracy would remain Lincoln’s “last, best hope of freedom.” I pored over Civil War picture books and even copied the wartime drawings from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly, which appeared in Fletcher Pratt’s Civil War in Pictures. The maps in the American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War especially enthralled me. They were pictures of the battlefields with drawings of tiny armies, North and South, smashing into each other at Bull Run, Spotsylvania, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Atlanta, Petersburg, and Appomattox.

But my bookishness doesn’t entirely explain why I fell in love with politics and became a Republican. My parents never expressed an interest in politics. My mother voted Republican in 1970 because I was working for the GOP, but in 1972 she voted for the Peace and Freedom Party, headed by radical Eldridge Cleaver, because my brother was supporting it.

Republicanism fit with my childhood of growing up in the Rocky Mountain West, a place of big horizons, long vistas, and most important of all, a palpable sense of freedom. There is something about the West that encourages individualism and personal responsibility, values I thought best reflected by Republicans. In the West, people tend to be judged on their merits, not their pedigree. From there, Washington seems undependable and a long way away.

At the age of nine, I decided I was for Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. I got my hands on a Nixon bumper sticker, slapped it on my bike’s wire basket, and rode up and down the block, as if that alone would get him a vote. Instead it drew the attention of a little girl who lived in the neighborhood. She had a few years and about thirty pounds on me and was enthusiastically for John F. Kennedy. She pulled me from my bicycle and beat the heck out of me, leaving me with a bloody nose and a tattered ego. I’ve never liked losing a political fight since.

At the age of thirteen, I was wild for Barry Goldwater. I loved that his philosophy celebrated freedom and responsibility, the dignity and worth of every individual, the danger of intrusive government, and the importance of politics to protecting those ideals. I had Goldwater buttons, stickers, and posters, a ragged paperback copy of Goldwater’s The Conscience of a Conservative, and even a bright gold aluminum can of “Au H2O,” a campaign artifact that played on the candidate’s last name. I got ahold of a Goldwater sign, but it didn’t last long in our front yard. I don’t know whether my parents or a supporter of Lyndon Baines Johnson removed it. LBJ not only crushed the Arizona senator, he also crushed me. I was devastated. But for budding Republicans like me, there was nobility in Goldwater’s loss. He went down with guns blazing and his ideology on full, unapologetic display. Goldwater was a “conviction politician,” the kind who shaped a movement.

Economics came on my radar screen when I was twelve or thirteen, when someone gave me a copy of Capitalism and Freedom, by Milton Friedman, one of the greatest defenders and advocates of capitalism. “Government power must be dispersed. If government is to exercise power, better in the county than in the state, better in the state than in Washington,” he wrote. Reading Friedman led me to next plow through Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. The pin maker, the division of labor, and the “invisible hand”—all of it made sense to me.

Then there was William F. Buckley, Jr. The Sparks, Nevada, library had a subscription to Buckley’s National Review magazine, with its unadorned cover and its bold credenda. I eagerly awaited its arrival each week, devouring articles using words I didn’t know (such as denouement) but whose meaning I could often guess. I couldn’t get my hands on Buckley’s books quickly enough. At age fifteen I laughed out loud all the way through The Unmaking of a Mayor.

When I took my first civics course in the fourth or fifth grade, and classmates were doing their first term papers on “Our Constitution” or “The Congress,” I was writing on the communist theory of dialectical materialism, since I had read Karl Marx. But I wanted a bridge from the world of ideas to the world of practical politics—and at fifteen, I received my first experience in government.

Between junior high and high school, I wrangled a summer internship in the Washoe County clerk’s office in Reno, Nevada. At the beginning of that summer, my family moved from Sparks to Holladay, Utah, near Salt Lake City. I stayed behind, living with my scoutmaster and his wife and spending the summer riding the bus to and from the courthouse to work. Somehow, filing papers and making photocopies in the clerk’s office seemed exciting and fresh. The process of government was thrilling. I spent most of my time filing crime and divorce papers, but I also watched trials and county commission meetings and even sat in on the Board of Equalization, though I couldn’t figure out what they were talking about, other than that it had to do with money and taxes. I was fascinated by county government and read whatever I could find about the esoteric disputes of county government theory.

Summer ended on a thrilling social note. On the final day of my internship, the cute eighteen-year-old clerk asked me to walk her home. Outside her apartment she gave me a quick kiss (my first). But the last bus from downtown Reno home to Sparks was fast approaching its stop a block away, so I had to bid her good-bye and run to catch it.

As we settled into a modest house in Holladay in the fall of 1966, I entered Olympus High School in suburban Salt Lake City feeling lost. I didn’t know anyone. I was a non-Mormon in a school where 90 percent or more of the students did follow that faith. I had no particular skill at sports or with girls. But I did have an ability: I could talk and argue. I was fortunate that at Olympus specifically, and in Utah generally, high school debate was a big deal, an activity where a bookish boy could find affirmation. I joined the debate team, found my tribe, and was off.

The coach, Diana Childs, paired me with Mark Dangerfield, who was a year ahead of me. Mark and I clicked right away. He had a great smile, a sharp mind, a competitive spirit, and the ability to scrape away some of my rough edges. We turned out to be alike in many ways.

For example, we were obsessive about preparation. We wanted better research and more of it than any of our competitors (a habit I still have to this day). We spent a small fortune on four-by-six-inch cards on which we wrote our information in precise block lettering or typed it with a small manual typewriter we had scored at a secondhand sale. We then meticulously arranged the cards in giant boxes behind dividers that made possible the quick recovery of facts, quotes, and authorities. I developed an elaborate color scheme to help us pluck just the right card at that special moment to confound the opposing pair of debaters.

In high school debate, you had to be ready to argue both sides of the question on a moment’s notice. So we pi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Description

- About Karl Rove

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Prologue: The Road to History

- Chapter 1: A Broken Family on the Western Front

- Chapter 2: King of the College Republicans

- Chapter 3: Planting Roots in Texas

- Chapter 4: What Is a Rovian Campaign?

- Chapter 5: Conquering Texas

- Chapter 6: A New Kind of Governor

- Chapter 7: Glimmers of the White House

- Chapter 8: The Grand Plan

- Chapter 9: Stung by New Hampshire, Rescued by South Carolina

- Chapter 10: The Big Mo’

- Chapter 11: The Cheney Choice

- Chapter 12: Derailed by a DUI

- Chapter 13: Thirty-six Days in Hell

- Chapter 14: The Real West Wing

- Chapter 15: Thinking Big

- Chapter 16: 9/11

- Chapter 17: Ground Zero

- Chapter 18: Striking Back

- Chapter 19: What Bipartisanship?

- Chapter 20: Joe Wilson’s Attack

- Chapter 21: Bush Was Right on Iraq

- Chapter 22: The Special Prosecutor and Me

- Chapter 23: Getting Ready for Kerry

- Chapter 24: Drugs and Marriage

- Chapter 25: Trapping Kerry, Making Peace with McCain

- Chapter 26: Suspense and Victory

- Chapter 27: The Democrats Unleashed

- Chapter 28: Anything for a Scalp

- Chapter 29: Katrina

- Chapter 30: Republicans on the Run

- Chapter 31: The Surge

- Chapter 32: Yes, It Was Fun

- Chapter 33: Leaving the White House

- Chapter 34: Rove: the Myth

- Chapter 35: Obama: the Myth

- Epilogue

- Photographs

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index